MAN OF MARBLE. MAN OF IRON. Andrzej Wajda’s Political Diptych

Two films that solidified Andrzej Wajda’s position both domestically and internationally. Two films that captivate while also stirring much controversy. This article is dedicated to Man of Marble (1976) and Man of Iron (1981).

Theoretically, one should speak of a triptych instead of a diptych – as Wałęsa: Man of Hope (2013) is considered a continuation of the highlighted films. While there are self-references and other elements connecting all parts, this article focuses solely on the first two, so (from a pre-2013 perspective) the term used will be diptych. Man of Marble Man of Iron

Man of Marble (initially shown in cinemas under the guise of a “reserved screening”) attempts to expose the communist propaganda’s falsification of history and contemporary reality – first the 1950s and then the 1970s, which remained deeply rooted in Stalinism, merely replacing old masks with new ones. This film marked a new chapter in Wajda’s career. After war films, the Polish director turned to contemporary themes (e.g., Innocent Sorcerers – 1960), then to the Napoleonic era (e.g., Ashes – 1965), and before filming the story of Birkut, he gained international fame with The Promised Land (1974). Notable is the thematic diversity, and as the director himself admitted, the success of one film necessitates searching for a new topic. The idea for a story about a Polish bricklayer from the Stalinist era arose in the early 1960s (with Mateusz Birkut to be played by Ryszard Filipski or Stanisław Mikulski), but the project was halted by the authorities (accusing the creators of attacking the leaders of labor). A decade later, the idea was revived, but the script had to be modified due to time constraints. In 1962, the action looked back twelve years to Stalinism, but by 1974, the gap had grown to nearly a quarter-century.

Let’s start with the director himself. Man of Marble is also a critical reckoning with Wajda’s past. On screen, Wajda confronts a period in his life when, as a film school student, he participated in making propaganda films about Nowa Huta – a city designed to rival the traditional and anti-communist Kraków. The filmmaker from Suwałki expresses his critical view of the socialist city, while also revealing that as a young man, he participated in the propaganda campaign for Nowa Huta. Evidence of this can be found in the film itself.

In Man of Marble, there is a subplot involving director Jerzy Burski (often seen as Wajda’s alter ego), who in the 1950s made propaganda films about the labor leaders from Nowa Huta (referred to as New Town in the original script). In the credits of the propaganda documentary within the film, Andrzej Wajda’s name appears as the assistant to the fictional filmmaker. Thus, the director exposes the propaganda practices of Stalinist cinema while revealing his active participation in them. This can be seen as a confession of guilt or a personal reckoning with that period of his life.

Man of Marble, at times with deliberate irony, portrays the idea of labor heroism. On one hand, it contains propaganda materials showing the manipulative power of mass media, while on the other, some scenes raise the question posed by the creator: to what extent was the idea of labor heroism a genuine attempt to elevate Poland from the bottom of Europe and create a symbol of Polish advancement, and to what extent was it mere manipulation? The times may seem colorful, but there is no doubt that it was just a facade.

Two parallel stories are told on screen – Agnieszka, who is making her diploma film (hence Wajda’s film is also self-referential), and Mateusz Birkut, a labor leader from the Stalinist era. He is the subject of the young director’s investigation, and his story unfolds with her increasing determination. We learn the most about him through film chronicles discovered by Agnieszka and third-party accounts.

Agnieszka’s character (whose name and status as a film student were inspired by Wajda’s colleague from the Łódź Film School, Agnieszka Osiecka) serves as a medium – telling the 1950s events from a contemporary perspective. For Agnieszka, the Stalinist era is ancient history, making her a bridge between the past and present, as a representative of the new generation with a keen interest in a specific historical period of her country.

Agnieszka, as a director, goes to great lengths to achieve her goal. She can be seen as an alter ego not only of Wajda but also of several other Polish directors of that era who faced various professional challenges. In Man of Marble, there is a scene where Agnieszka complains to her father that television has taken away her film and camera, preventing her from completing her film about Birkut. Didn’t similar problems plague Polish filmmakers, especially documentarians?

I mentioned earlier that the director’s alter ego is often considered to be the character Burski, while I pointed to Agnieszka. I believe these two views do not conflict. Consider this: Burski, an artist of the older generation, begins to identify more closely with Agnieszka over time, approving of her attitude, thus aligning with the new generational thought. Wajda does the same, trying to break away from his past work. Agnieszka can be seen as the author of Man of Marble, considering her struggles with the authorities, something Wajda knew well from personal experience. One might add “young” Wajda, but his fight with censorship extended beyond the early stages of his film career, as evidenced by the realization of the discussed work when the Suwałki-born creator was fifty years old.

Wajda encouraged Krystyna Janda to maintain a passionate demeanor, which yielded positive results. Agnieszka’s character is determined, dedicated to her work, and symbolizes a reborn society. Her determination and willingness to cross certain boundaries of proper conduct are well illustrated in the famous scene with the statues. The student’s cameraman has a different idea for capturing the sculpture. Agnieszka takes matters into her own hands, literally, deciding on the shape of her work not only as a director but also as the direct author of the shots. This symbolizes breaking the barrier that, at that time, separated artists (not just filmmakers but also writers) from all historical archives and collective memory.

The film captures the vitality with which Agnieszka pursues her mission. Excellent cinematography by Edward Kłosiński (note the filming style – the camera is positioned at the actress’s waist height or slightly below, adding dynamism to the character), Andrzej Korzyński’s music, and deft editing – all these elements follow the actors, who set a lively rhythm for the entire work. The protagonist fights for her goals to the end, a trait that emerged in the updated script. Notably, in the 1960s script, the character was unable to speak with Birkut when she finally found him. When reminded by her crew that she needs to complete her diploma film, the girl responds, “I’ll have to make something else. And we’ll finish this when we can,” adding quietly, “Because I think someday we’ll be able to.”

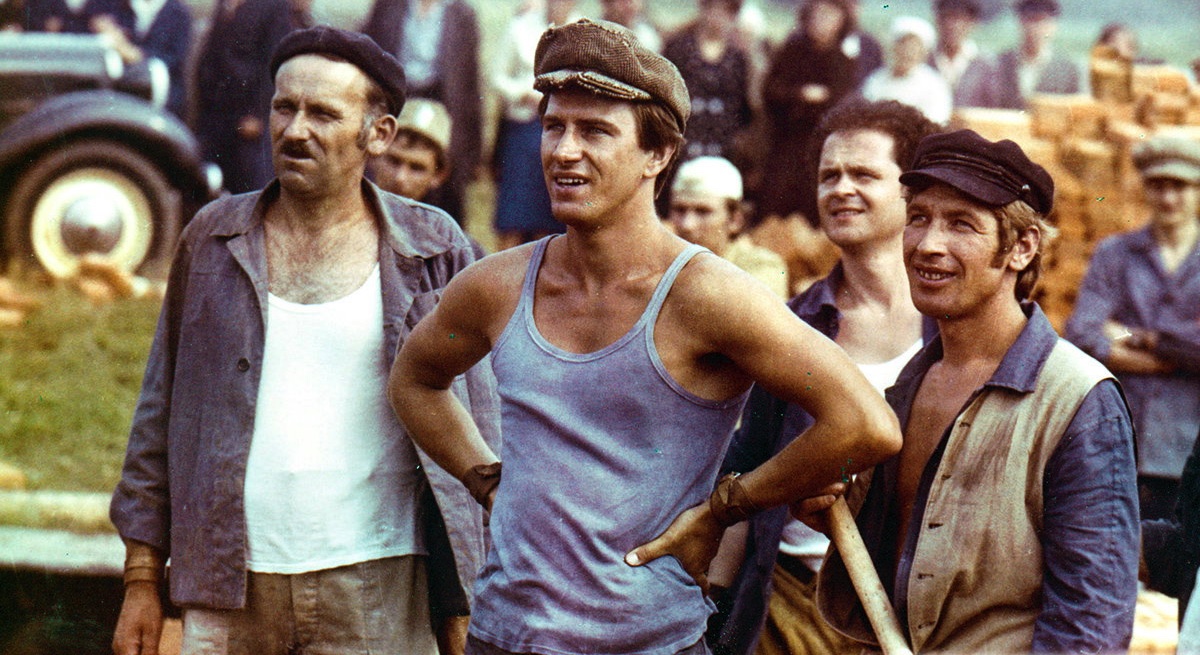

The strength of Man of Marble lies in centering its narrative on another highly suggestive character, Mateusz Birkut. He is a worker symbolizing a multitude of people in that profession, on whose behalf power was exercised. In Wajda’s film, the worker speaks with his own voice and evaluates that power.

Jerzy Radziwiłowicz plays two characters in the discussed diptych (Mateusz Birkut and his son, Maciej Tomczyk), a not uncommon occurrence in cinema, but one that cannot be overlooked here. Reportedly, only once in Wajda’s directing career did an improvisation during screen tests become an actual part of the film. This was due to Radziwiłowicz, who, in one of the rehearsed scenes, was so convincing that the director felt no further improvement was needed.

Interesting is the transformation Birkut undergoes: from a somewhat lost man from a small village, initially overwhelmed by events and naively manipulated into becoming a labor leader, he evolves into a folk rebel, aware of his situation and refusing to be deprived of his dignity. The concept of awareness is crucial. Birkut gradually gains awareness, eventually being cast out of the system, with his previously naive set of values collapsing. Agnieszka, too, gains awareness, discovering the falsity of language and the misrepresentation of reality. This awareness also extends to her collaborating crew (often seen as a symbol of society), whose members are age-diverse – the cameraman represents the older generation, the sound technician the younger, and the editor the middle-aged, bridging the gap between them.

The authorities could censor scripts and cut scenes or individual lines (such as Agnieszka’s remark upon first arriving in Nowa Huta: “What a horrible architecture,” interpreted as a veiled critique of a local Lenin monument), but they couldn’t foresee the impact of the powerful and authentic performances during script readings. Such full-blooded and convincingly realistic portrayals were unlikely to please the communist establishment, but completely removing the characters was no longer an option.

The meticulously prepared set design and the aforementioned quality of the cinematography deserve attention. It is no surprise that Wajda, alongside cinematographer Edward Kłosiński and set designer Allan Starski, spent many hours watching film chronicles from that era to skillfully stylize the scenes they were currently shooting to resemble those of the past.

At times, the makeup is a bit less satisfactory. An example is the scene where there is a top-down order to shave a group of workers. However, Birkut’s face, as well as that of several of his colleagues, is not covered in stubble. The characters are already shaved, which could have been avoided by allowing the actors to grow at least a three-day beard. Naturally, these are nuances, but in such a memorable scene, they are particularly noticeable.

In his autobiography, Wajda emphatically stated that Man of Marble was not based on the life story of Piotr Ożański, who even wrote a letter to the director. The builder of Nowa Huta praised the quality of the film but added: “It’s just very sad for me; people watch my feats on screen, and I get nothing from it. Please think about this matter.” Wajda saw justification for the former labor leader’s disappointment but assured that Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski’s script comprised many anecdotes drawn from life, rather than any single story.

At this point in the text, let’s move on to the second part of the diptych. Man of Iron contains a scene that literally connects it to its predecessor, as it was indeed filmed with the intention of being part of Man of Marble. This is the famous moment where Agnieszka does not find Birkut’s grave and leaves flowers stuck in the gate. Naturally, those overseeing the film’s production stated that the scene had to be removed because there were no unburied victims of the December events. Wajda cut the scene, only to return to it a few years later.

The film was shot from January to April, which was beneficial for reconstructing the December events but simultaneously made it difficult to recreate the August atmosphere. Agnieszka’s character was moved to the background (which doesn’t mean she isn’t important for the continuation of Man of Marble). Instead, Winkel emerged, somewhat taking over her role – initially envisioned to be played by Zbigniew Zapasiewicz, but ultimately portrayed by Marian Opania. Wajda justified his change by pointing to the second actor’s physical traits being more suitable for the character.

Man of Iron is the first of Wajda’s films made to order, which could have been a drawback for the upcoming production. The continuation of Man of Marble was made quickly, from one day to the next. The challenge Wajda undertook was linked with constant changes regarding the overall idea: the creators learned of new facts that they had to include in the film, while other information had to be cut. The script difficulties were enormous; Ścibor-Rylski didn’t have excessive comfort in writing, and in some dialogues, he was assisted by Agnieszka Holland. He was also provided with numerous tape recordings, notes, speech fragments, leaflets – often these materials belonged to “ordinary” people who reacted this way to the news about the film being prepared. Such working conditions, on one hand, a wealth of material, on the other, massive time constraints, had to impact the quality of the emerging work. The need to complete it as quickly as possible also stemmed from the desire to submit the film to festivals (especially at the peak of interest in Poland and “Solidarity”), which will be revisited later.

The situation can be viewed in two ways. On one hand, there are numerous glaring editorial mistakes, almost amateurish (e.g., in the scene where Winkel wipes up spilled alcohol in the bathroom), and some threads should have been shown better (however trivially I may have put it at this point). On the other hand, given such little comfort of work and almost zero support from the authorities, other aspects should be appreciated. The tragic shooting at the railway viaduct in Gdynia was well portrayed, and realism was maintained despite General Jaruzelski’s refusal to lend tanks, and no actual MO (Citizens’ Militia) officers participated in the scene. It remains a mystery how they managed to obtain those dozens of uniforms and dress extras in them. This is just one of several examples of excellently staged events (probably due, among other things, to the epic scale of the filming, which helped build the myth of “Solidarity”), so there is no excessive contrast between the dominant narrative part of the film and the documentary inserts (e.g., scenes showing arrests on the street in 1970, which were originally supposed to be cut). Some authentic events (e.g., scenes of signing the August Agreements) were supplemented with staged shots, which did not harm the film but rather highlighted Wajda’s directorial craftsmanship.

In Man of Iron, it’s also worth paying attention to Allan Starski’s set design. Although many scenes were shot in front of the actual shipyard gate, there were moments when the only solution was to return to Warsaw. At the Film Studio, Wajda’s set designer meticulously recreated a corner of the shipyard porter’s lodge, along with the gate, and there they shot the missing scenes. The impression of authenticity was maintained.

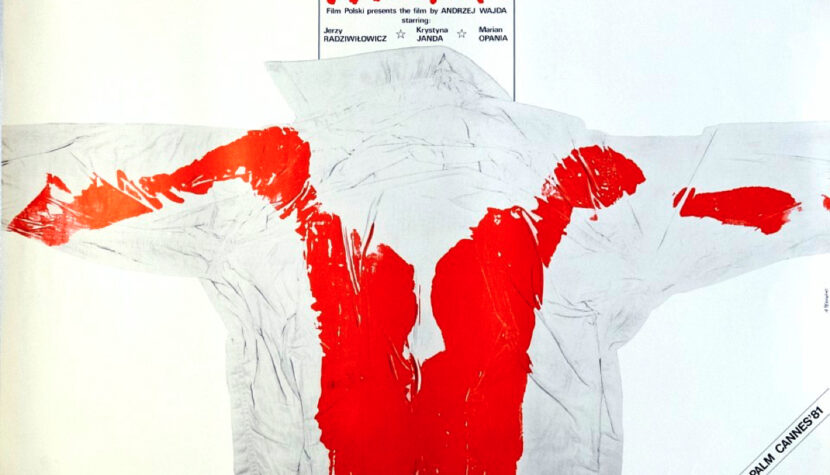

Editing and sound work, however, were done in a mad rush to make it in time for the Cannes festival, where “Man of Iron” was invited. The creators hoped that the international acclaim of their work would expedite its release to the domestic audience. Winning the Palme d’Or can be argued to result from what is strongest in “Man of Iron”: capturing spectacular historical events at the moment of their birth, with the presence of real characters (Lech Wałęsa and Anna Walentynowicz) and demonstrating their fictional variant with a series of social and cultural contexts. Serious technical shortcomings seem overshadowed.

Undoubtedly both Man of Marble and Man of Iron these are very important and simultaneously controversial films. They provoke thought and consideration even today. Surely right from the start, when we think about their subject matter. Thus, I encourage readers to share their own opinions.