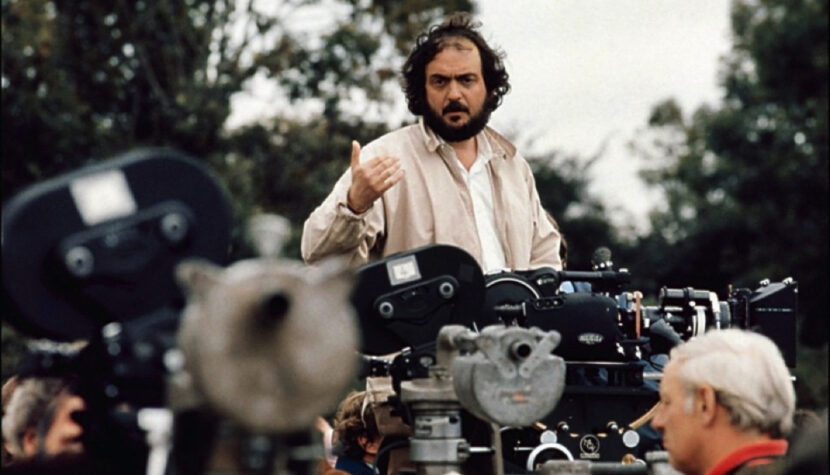

Full filmography of Stanley Kubrick, cinematic genius

“So Steven Spielberg died and went to Heaven. Archangel Gabriel greets him at the blue gates and says, “God loves your movies. Make yourself at home here. I will fulfill your every wish.” Spielberg replied: “I’ve always wanted to meet Stanley Kubrick. Can you set us up?” Frustrated Gabriel replied, “I can’t really do that for you. Stanley doesn’t want any meetings. I’m sorry.” Suddenly, they both see a bearded man in an army jacket riding a bicycle. Spielberg yells, “Look, it’s Stanley Kubrick! Can you stop him?” And the Archangel Gabriel whispers, “It’s not Kubrick. It’s a God who thinks he’s Kubrick.” Kubrick loved this joke.

Paths of Glory (1957)

World War I. French generals issue an absurd order to attack a hill occupied by the Germans. A suicidal attack order is given to the unit of Col. Dax. The attack ends with the withdrawal of the rest of the unit to the trenches. Enraged, General Mireau orders his own soldiers to be shot at. The artillery commander refuses, so Mireau accuses Col. Dax for cowardice and puts three soldiers before a court martial…

The first Kubrick’s masterpiece. The horrors of war, as a “natural” component of the presented world, are contrasted with the institutionalized cruelty of the generals. The mass massacre at the front seems to be nothing compared to the inevitability of the puppet trial of three innocent soldiers, randomly selected as a result of the generals’ attitude terrifying in their detachment from reality. War is war, but Kubrick clearly shows where the real evil sits. Not in magazines and barrels, but in the minds of people for whom an army regiment is just a statistic that can be freely shaped in the name of cosmically overblown, individual whims.

This issue in various variants will be the basis of many subsequent films by Stanley Kubrick, clearly fond of dressing moral paradoxes in military uniforms. White and red, feelings and orders, weakness and drill, reason and absurdity, the dirt of the trenches and the splendor of the drawing rooms, and after many years also Pyle’s brain on the tiles of a soldier’s shitter in Full Metal Jacket – on the front of the struggle of order and madness, Kubrick was an exceptionally keen observer. The ironically titled Paths of Glory is just the beginning.

Although Paths of Glory looks like a creative illustration of an artistic thesis about the struggle between the light and dark sides of humanity, these events really took place on the front lines of World War I in 1915. 20 years later, they were described by Humphrey Cobb in the novel Paths of Glory. Although set in France, the crushing portrayal of the French generals precluded shooting there (for this reason the film was banned in France until 1975). Kubrick shot Paths of Glory in Germany, on locations near Munich, in the museum interiors of Schleissheim Castle and in Geiselgasteig Studios.

It almost didn’t come to fruition at all. Kubrick and Harris bought the film rights to Paths of Glory, but MGM’s Dore Schary refused to finance the production, directing the filmmakers’ attention to Stefan Zweig’s The Burning Secret. Kubrick, along with Calder Willingham, began adapting Zweig’s novel while also working (illegally) on Paths of Glory. After Schary’s departure from MGM, the developers were left stranded with both projects. The last resort was Kirk Douglas, actor and producer, owner of Bryna Productions, with which Kubrick and Harris signed a contract for five films. Douglas was so enamored with the unwanted script of Paths of Glory that he blackmailed United Artists into paying $805,000. dollars for a Kubrick film, and of course he played the lead role of Colonel Dax. Thinking about box office receipts, Kubrick considered a happy ending, but ultimately left the original, bitter ending of Cobb’s novel.

Great tracking shots from the trenches required their extension by 60 cm in relation to the historical truth. Only then did the camera cart fit into the decoration. Kubrick’s legendary perfectionism, manifested in endless doubles of single shots, was also present on the set of Paths of Glory. He repeated the shot of bringing food to the convicts 68 times, each time with a new piece of food on the tray. One of the falsely accused soldiers was Joe Turkel, the memorable bartender from The Shining.

For the only female “spoken” role of a German girl singing for French soldiers in the film’s touching finale, Kubrick chose 24-year-old German Christiana Harlan. This inconspicuous decision influenced the rest of Stanley Kubrick’s life. Christiana divorced her husband to marry Stanley a year later and moved to the USA with her daughter Katharina from her first marriage. They were married until Stanley Kubrick’s death in 1999.

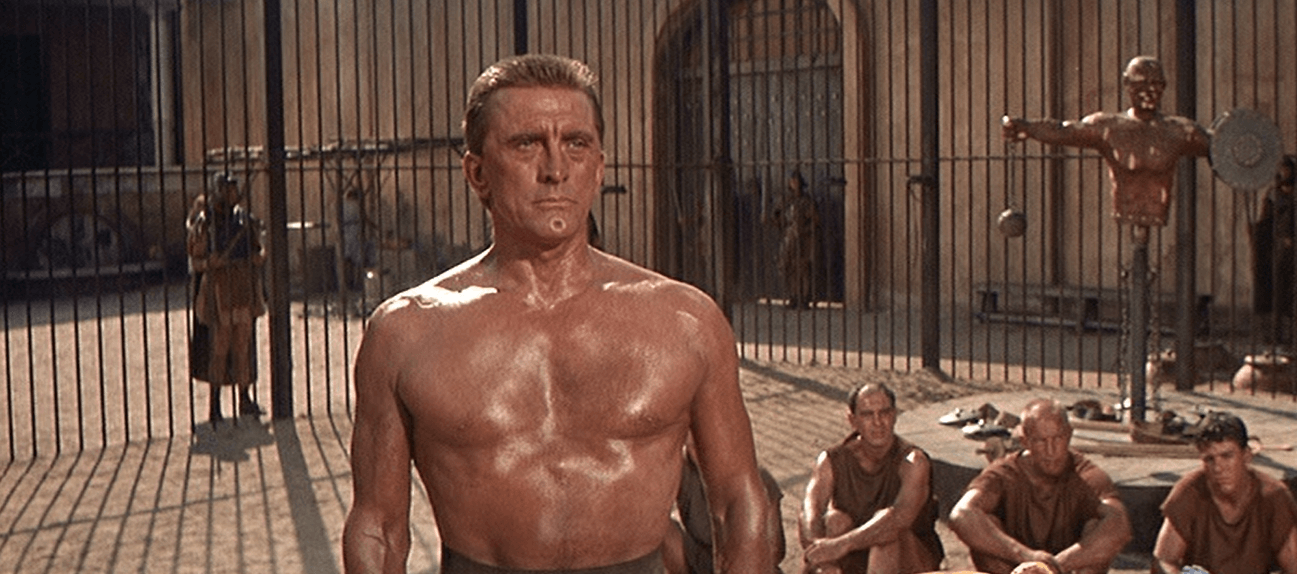

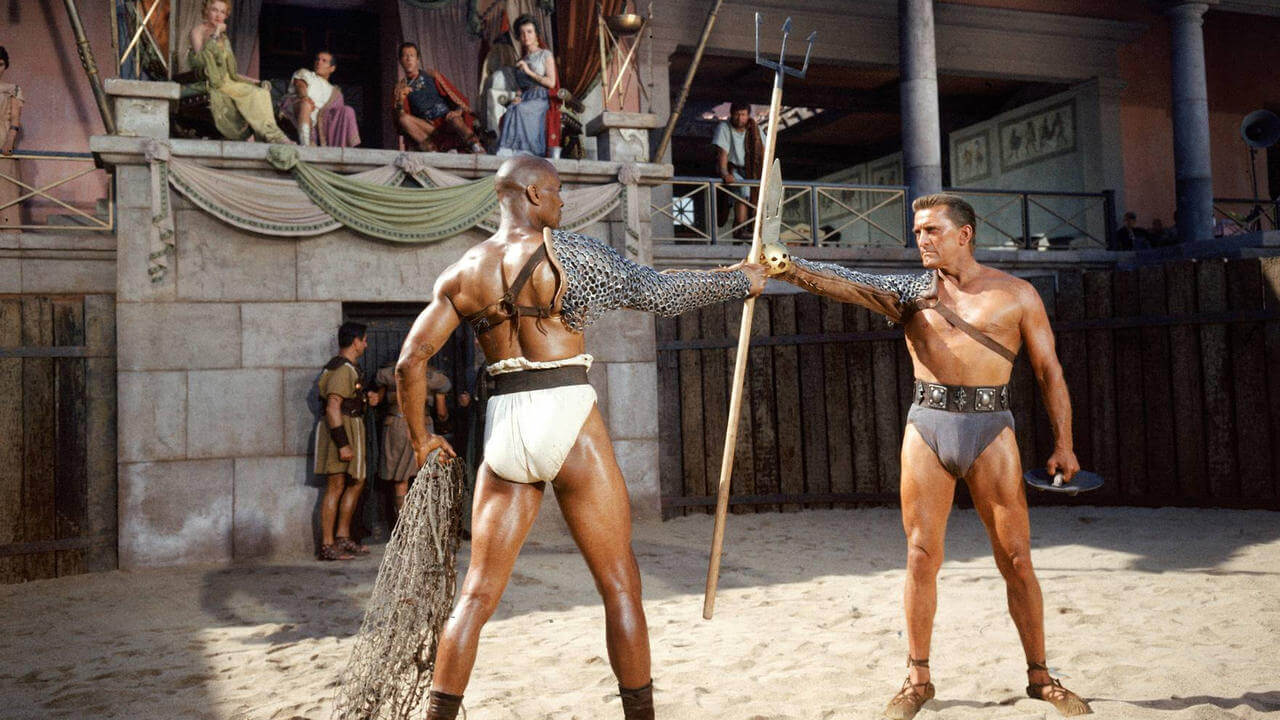

Spartacus (1960)

The proud slave Spartacus, after injuring a guard in a quarry, gets into Batiatus’ school for gladiators. Here he learns the secrets of fighting and falls in love with the slave Varinia. After the slaves revolt, Spartacus leads them towards the sea. But instead of ships, the slave army awaits the final battle against the mighty Roman troops…

Among the lesser-known facts of Kubrick’s life, there are traces of work on film projects that never saw the light of day, or those on which Kubrick worked only briefly, only to part with unwanted ideas due to misunderstandings. In the 1950s, Kubrick and Calder Willingham (co-author of Paths of Glory) worked on the aforementioned adaptation of Stefan Zweig’s novel The Burning Secret, but changes in MGM management stopped this work (the film was not made until 1988, directed by Andrew Birkin, Kubrick’s assistant on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey).

Kubrick and Harris also worked on a World War II project, The German Lieutenant, based on Richard Adam’s novel, which came to nothing, as did the screenplay I Stole 16 Million Dollars, written especially for Kirk Douglas, based on the biography of a burglar Herbert Emerson Wilson. It was the same with the project of the movie The 7th Virgina Cavalry Raider or the series based on the movie Operation Mad Bull. After filming Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick was hired by Marlon Brando to write the script for One-Eyed Jacks (replacing Sam Peckinpah), but after six months of contracted fruitless work and jostling, Kubrick gave up on both the script as well as the planned directorship of this film (the 1961 western was eventually directed by Brando himself). In the late 1950s, Kubrick found himself in an artistic and professional void.

At the same time, Kirk Douglas, angry that he didn’t get the part of Juda Ben-Hur, decided to make his own peplum movie and began a mammoth ($12 million) production of Spartacus. But only a few days of shooting were enough to spark a conflict with Universal’s imposed director Anthony Mann, whom he immediately thanked for his lack of cooperation. Behind-the-scenes rumors pointed to Mann’s genteel directing style as a source of conflict, as opposed to Douglas’s very physical acting; the star simply wanted to make a good, spectacular action movie, and Anthony Mann opted for an elegant, very traditional costume film. Spartacus was in trouble from the start.

Then Kirk Douglas, remembering the excellent cooperation on the set of Paths of Glory, offered Kubrick to take over the directing. It was Friday, February 13, 1959, and by the following Monday Kubrick would make his decision. By blind chance, more social than creative, Stanley Kubrick made the only film in his career over which he had absolutely no control, over which he had no say, and which was basically a job for a friend who pulls all the strings. However, it is hard to imagine Spartacus without Kubrick’s sophisticated directorial and visual invention, which less discreet industry experts did not fail to mention to Douglas.

Working during the days of Senator McCarthy’s infamous “witch hunt”, Kirk Douglas hired the stigmatized screenwriter Dalton Trumbo to adapt the novel by fellow Communist sympathizer Howard Fast. Writing under several pseudonyms since 1950, Trumbo, thanks to Douglas’ uncompromising attitude and Universal Pictures’ favorable attitude, appeared on the payroll under his own name, which marked the end of the McCarthy era (although earlier Kubrick himself agreed to sign the script with his own name).

Among the festival of peplum mega-productions of Hollywood (The Robe, The Ten Commandments, Quo Vadis, Julius Caesar, Ben-Hur, and later also Cleopatra and The Fall of the Roman Empire) Kubrick and Douglas’ film stands out mainly due to the lack of Christian-religious accents. Although Spartacus at first glance consists of the same attractions (long, dialogue scenes interspersed with outdoor mass-battle sequences), its most important feature is… the lack of boredom. Kubrick’s burgeoning narrative genius, though limited by the script material imposed from above, did not allow for the typical for peplum prolonged pompous dialogues, nonchalant handling of rough-hewn psychological portraits, cheap demagoguery or imbalance between rhetoric and action.

An additional difficulty for the 30-year-old director was working with acting legends – Laurence Oliver and Charles Laughton, whom he directed with the skill of an oldtimer. Spartacus was also a unique opportunity for him to face the realities of the blockbuster in a purely physical way. He played the great sequence of the final battle with the help of nearly 10,000 extras chased back and forth across the Spanish wilderness for six weeks; the entire film was shot in 167 days, mostly on Universal grounds and in Death Valley.

The desire to give as much of himself as possible led to the marginalization of Russell Metty, the cinematographer. Kubrick took over much of the camera and lighting work, leading an embittered Metty to consider removing his name from the payroll. The bitter compensation for him was an Oscar for cinematography in Spartacus, a job for which he was responsible to a relatively small extent. Thanks to Kubrick, the role of Varinia was taken by Jean Simmons, who had previously turned down the role. Kirk Douglas quickly found himself replacing the inconvenient Mann with an even more maverick Kubrick, which didn’t end up with kicking his friend off the set, but seriously undermined their friendship. Douglas said, “Kubrick will be a great director someday, but first he has to fall on his face at least once. That will teach him to compromise.” Well, looking at Kubrick’s artistic path, it is clear that he owed his own greatness to his implacable dictatorship, which did not recognize any compromises.

Not all ad hoc changes were Kubrick’s. The wonderful Peter Ustinov, who won an Oscar for the role of Batiatus, himself corrected the dialogues he conducted on the set with Charles Laughton (Gracchus). Thus, Peter Ustinov became the only actor to win an Oscar for his role in Kubrick’s movie. Later brilliant performances by Peter Sellers ended their Oscar life only in nominations. Apart from as many as five different edits (censorship issues have changed over the years), Spartacus is also Kubrick’s only film that has an official extended version (The Shining, 30 minutes longer, was shown in American cinemas, compared to the shortened, well-known 115′ version, intended for cinemas in the rest of the world).

In 1991, the DVD edition of Spartacus was expanded to include a scene between Laurence Oliver and Tony Curtis suggesting a homosexual theme. The latter personally worked on the new post-syncs for this scene, and the late Oliver was voiced by Anthony Hopkins himself.

Lolita (1962)

Humbert Humbert begins an affair with Charlotte Haze while falling under the spell of her 13-year-old daughter Lolita. After the wedding, Charlotte finds out about Humbert’s feelings towards Lolita, runs away and dies in a car accident. Humbert stays with Lolita, who falls ill and ends up in the hospital, from where she mysteriously disappears. Humbert suspects playwright Quilty of involvement in a case…

Despite 4 Oscars for Spartacus, fame and splendor worthy of recognized masters of Hollywood, Stanley Kubrick valued full artistic independence above all else. The lack of control over Spartacus deepened this state. From then on, the director was the undivided ruler of the film set, the god of his own worlds, the only instance to which the dissatisfied could appeal. And the Hollywood establishment did not miss such creative assumptions in the slightest. Kubrick, although he could work for any label, but only on his own terms, decided to produce independently and as far as possible from Tinseltown.

Still during the production of Spartacus Kubrick and Harris for 150 thousand dollars bought the rights for Vladimir Nabokov’s scandalous novel Lolita (as well as another, almost identical book by the writer Laughter in the Dark, only to prevent the competition from making a similar film), and also offered the writer to write the script. Especially the latter decision seems quite strange in view of Kubrick’s dictatorial tendencies, but the director himself made so many corrections during the production that Nabokov said years later that if he had known how much Kubrick would change in his own work, he would never have undertaken to write the script.

Lolita itself was already scandalous enough on paper for the extremely puritanical America of the time. The relationship bordering on pedophilia between an erotic teenager and a middle-aged man was seemingly not in Kubrick’s sphere of interest, as he preferred to bring to the screen less known stories that explore the madness of the human spirit more deeply. Love seemed a feeling lacking enough psychological depth to Kubrick’s obsessions.

But Lolita disrupted conventions, caused anxiety and provoked. Just like Kubrick. Like the heroes of his later films, also prof. Humbert Humbert is a victim of his own madness, a man running away from the so-called normality. A peace-of-mind, unwanted marriage to the possessive, though madly loving widow Charlotte ends in tragedy, which is Humbert’s salvation.

His midlife crisis had him blindly following the nymphet Lolita, as sweet and alluring as she was youthfully reckless and vulgar. He made fun of Charlotte’s true feelings to fulfill every whim of a capricious teenager. He hated Charlotte’s obsession with jealousy, but later he became morbidly suspicious of Lolita as well. This seriously treated melodramatism was dressed by Kubrick in an almost 2.5-hour-long, emotional spectacle, unexpectedly saturated with perverse humour.

It’s not just about gag scenes (the screening of The Curse of Frankenstein in a drive-in theater or the unfolding of a bed in a hotel room). Scenes with Peter Sellers, an actor – chameleon in make-ups reminiscent of the Pink Panther, speaking in different voices at the speed of a machine gun, burst with black humor. His Clare Quilty are several versions of the same character, and each impresses with its almost stunning acting perfection.

Cary Grant, Marlon Brando, David Niven, Laurence Oliver, Peter Ustinov and even Errol Flynn were considered for the role of Humbert Humbert. James Mason was the first candidate, but had to decline the first time due to theater commitments. Out of nearly 800 girls, Kubrick chose Sue Lyon, supposedly because of her relatively large breasts – if they were smaller, the censors would look less favorably on the relationship of a teenager with an adult man. Kubrick and Nabokov, also due to anticipated censorship objections, increased her screen age from 12 to 14.

In the opening scene, Peter Sellers says “I am Spartacus. Have you come to free the slaves?” As you can guess, this text was not written by Nabokov (who received an Oscar nomination for Lolita), but by Kubrick himself, recovering from his previous film. Working on Hollywood’s money-independent Lolita (the Warner Bros. wanted to produce the film for $ 1 million, but with the right to interfere), forced the film to be shot in Great Britain, where the source of financing came from (made in 88 days, Lolita ended up costing 2 million dollars). In 1961, Kirk Douglas agreed to terminate his unfulfilled contract with the Harris and Kubrick company for a fee, thanks to which a year later both men were completely independent. This intimate story about the obsession of forbidden love was the first film Kubrick made in Britain.

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

The deranged General Ripper sends planes over the USSR to carry out a nuclear attack and switches them to a secret communication code. The US president offers the Russians to shoot down their own planes. Ripper’s subordinate guesses the code, but the last plane has a broken radio and does not receive information about the aborted attack. The President’s adviser, former Nazi Dr. Strangelove, offers to go down to the mines for 100 years…

Where common sense ends, the military begins. Kubrick also knew this simple truth and used the uniforms for the second time, but this time on a global scale. Never before or since have Cold War thinking been so ruthlessly exposed. In planning the screen adaptation of Peter George’s otherwise serious novel Red Alert, Kubrick came to the conclusion that the atomic threat in the hands of the mentally tainted generals is so disturbingly grotesque that there is nothing left but to shift the problem slightly in the direction of absurd comedy.

For this purpose, he engaged screenwriter Terry Southern, at the instigation of Peter Sellers. What is most terrifying about this extremely funny film is the cold, precise, Kubrickian logic drawn from a chain of cause and effect, initiated by the fantasies of an impotent general who “denyed women his essence.” Hermetic language of orders and military terminology was deliberately used to construct most of the dialogue. First of all, Kubrick unmasked the illusion of officer madness here, making the uniformed actors deliver the most sensible and understandable lines, but in the context of an abstract global annihilation, completely incompatible with the seriousness of the situation. Again, the joyful use of statistics, already present in Paths of Glory – Gen. Turgidson, with the lightness of a cosmonaut in a vacuum, blurts out the projected losses in the civilian population, reaching millions of human lives, encapsulated in smooth rhetoric with percentages in the lead role.

Government civilian employees were also mocked, with the irritating US president and drunken USSR prime minister Kissoff (kiss off) on the other end of the telephone hotline. Laughter mixes with horror – is this what a crisis team to prevent World War III is supposed to look like? After all, these lunatics need to be locked up as soon as possible and forbidden to play even with plastic soldiers. Meanwhile, Kubrick is having a great time, and so are we. Why? Well, the director again performed his signature trick, making a kind of reversal of optics.

Enthusiasm of General Turgidson (absolutely fantastic George C. Scott), delighted with the atomic perspective, is also contagious to the viewer. And above all, we keep our fingers crossed for the successful mission of the B-52 bomber, which is the only one that continues its flight over the Soviet ground to make an atomic drop. Although the viewer knows what is at stake in the success of this mission, he hopes that our boys, whom we have liked throughout the film, will manage and, as befits true Yankee patriots, will return home with the famous melody “When Johnny comes marching home” on the lips. Not true – after this war they won’t even come back with clubs (as predicted by Einstein). They won’t come back at all. But does it matter? After all, all that matters is protecting the American way of life from communist henchmen. After the nuclear attack and counterattack by the Russians (the Doomsday Machine mentioned by Strangelove), there will be nothing left to defend, and the last human sounds will be the monkey screams of Major Kong as he rides an atomic bomb in an ecstatic frenzy.

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (the longest title ever nominated for an Oscar in the Best Picture category) is a festival of outstanding creations. Of course, the leader is the incomparable Peter Sellers, playing three completely different characters – the level-headed Captain Lionel Mandrake from the Burpelson base, annoying US President Merkin Muffley with his egghead calmness, and the titular Dr. Strangelove, former adviser to Adolf Hitler. Just like in Lolita, here too Sellers gave free rein to his incredible acting skills of metamorphosis, which is most evident in the final conversation between the president and Strangelove, where he was in dialogue with himself and with each cut he was someone else. In the script, President Muffley was supposed to be seriously ill. Sellers played it so convincingly and intensely that the other actors burst out laughing, ruining takes one after another. In the end, Kubrick reshot everything, but he had Sellers act seriously, without comedic charges.

Remembering his performance in The Killing, Kubrick brought the retired Sterling Hayden to the set, who with a wonderfully comic seriousness played General Jack D. Ripper, obsessed with the vision of “nuclear fight with the Russians” (a clear allusion to Jack The Ripper). Next to Norman Bates from Psycho, General Ripper is perhaps the most expressive on-screen study of the madness of those years. But the most surprising creation was created by George C. Scott, who considered his daring charging in the role of General Buck Turgidson his best role. Indeed – who remembers his Oscar-winning role in Patton and his almost bronze image of the titular general, must admit that transferring this stone face and this monumental figure to the world of Stanley Kubrick’s absurd comedy could not but give a staggering and funny effect.

The director applied a very interesting trick to Slim Pickens, who plays Major “King” Kong, the commander of the bomber. Well, Kubrick did not inform the actor that the film was a black comedy, did not give him the script, except of course his dialogues, and told him to play it completely seriously. The clash of seriousness of Kong’s pathetic and sometimes idiotic speeches with the absurdly twisted context of the film gave the desired effect of surrealism. The role of Slim Pickens was originally to be played by Peter Sellers (this would be his fourth role in this film), but Sellers’ genius collided unexpectedly with Kong’s Yankee accent. Sellers’s breaking of his leg precipitated Kubrick’s decision to hire the natural Southern-accented Slim Pickens (John Wayne had not even responded to the offer beforehand), whom he remembered from his would-be collaboration on One-Eyed Jacks.

Although the film was made with Columbia money, Kubrick shot it at Shepperton Studios in the UK for two reasons: Peter Sellers’ divorce proceedings prevented the actor from crossing the border, and Kubrick himself liked the country quietness away from the hustle and bustle of Hollywood so much that he decided to stay here. Among the film’s working titles were The Edge of Doom and The Delicate Balance of Terror. The line of Major Kong commenting on the contents of the emergency kit (“would be enough for a nice weekend in Las Vegas”) originally referred to Dallas, but after the assassination of Kennedy, the name of the city, sensitive to the American public, was changed. For the same reason, the premiere, scheduled for December 12, 1963, was postponed to January of the following year.

The Playboy spread, read aboard a B-52 bomber, features Tracy Reed, the same actress who played General Turgidson’s secretary. She was the only female character in the film. In Dr. Strangelove the black man James Earl Jones, later known primarily as the voice of Darth Vader, made his big screen debut. In A Clockwork Orange, the bodybuilder David Prowse, who played Darth Vader in the old Trilogy, appeared in a small role as the writer’s guardian. CRM-114, the code name for the cipher machine on board the bomber, will be used by Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Dr. Strangelove’s condition, manifested by uncontrollable movements of the limbs, is a genuine neurological condition. After the film, it was dubbed “Dr. Strangelove Syndrome”. Production designer Ken Adam (later also worked on many Bonds) designed the interior of the bomber according to scarce official data, because the military refused to cooperate due to the mocking subject matter. Nevertheless, the decoration of the plane was so detailed and in accordance with the facts that the command of the US Air Force suspected a conspiracy and the theft of authentic, top secret data (which ironically confirmed the thesis presented in the film about the ease of succumbing to conspiracy theories by representatives of the army obsessed with secret clauses). The original ending, in which General Turgidson’s subjugation of the Soviet ambassador ended in a great food fight in the War Room, was completely omitted from the film. No footage has survived from this sequence, only a few photos. Optically processed, unused aerial shots were used by Kubrick in the journey sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

This nuclear grotesque was Kubrick’s last collaboration with James Harris. The two men parted amicably after Lolita. Harris wanted to make films himself, but when he left, he helped Kubrick in the pre-production stage of Dr. Strangelove. In conclusion, it is worth adding that Kubrick, when writing the script, came up with a crazy idea to fasten all events with a plot frame with Aliens watching little earthly madness from space. There are no traces of this concept in the finished film, but if this was really the case, it is a fascinating clue leading directly to the plot premise of his next film. Leaving behind all the hype surrounding the Dr. Strangelove controversy, Stanley Kubrick moved into his new British headquarters in Abbott’s Mead and began preparing his most famous film…

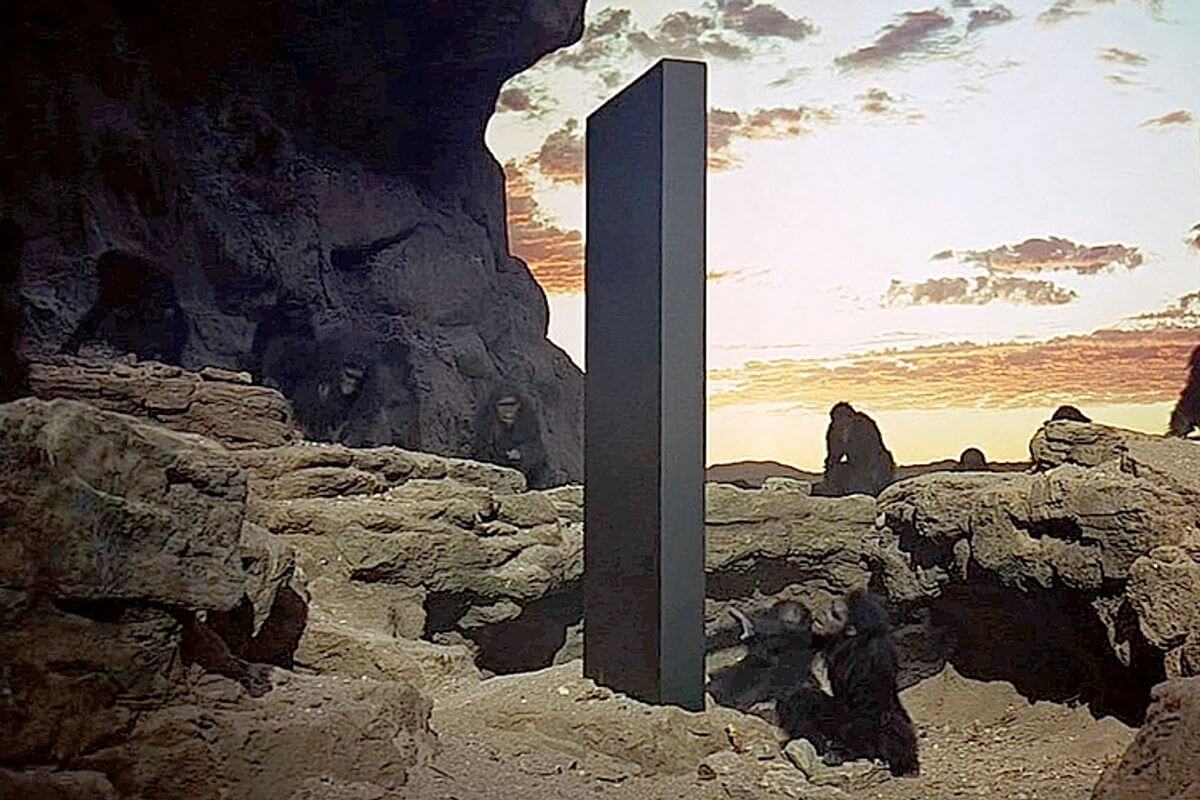

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

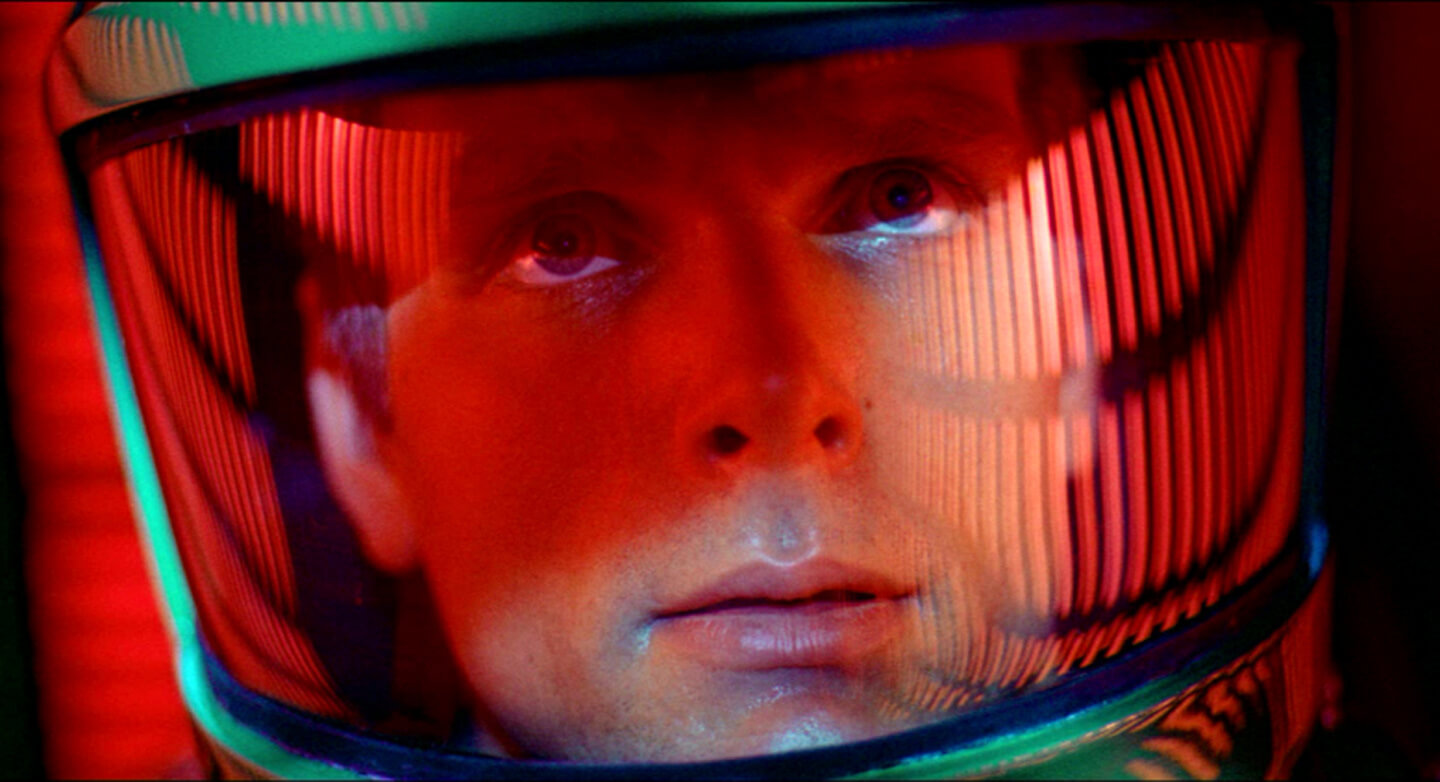

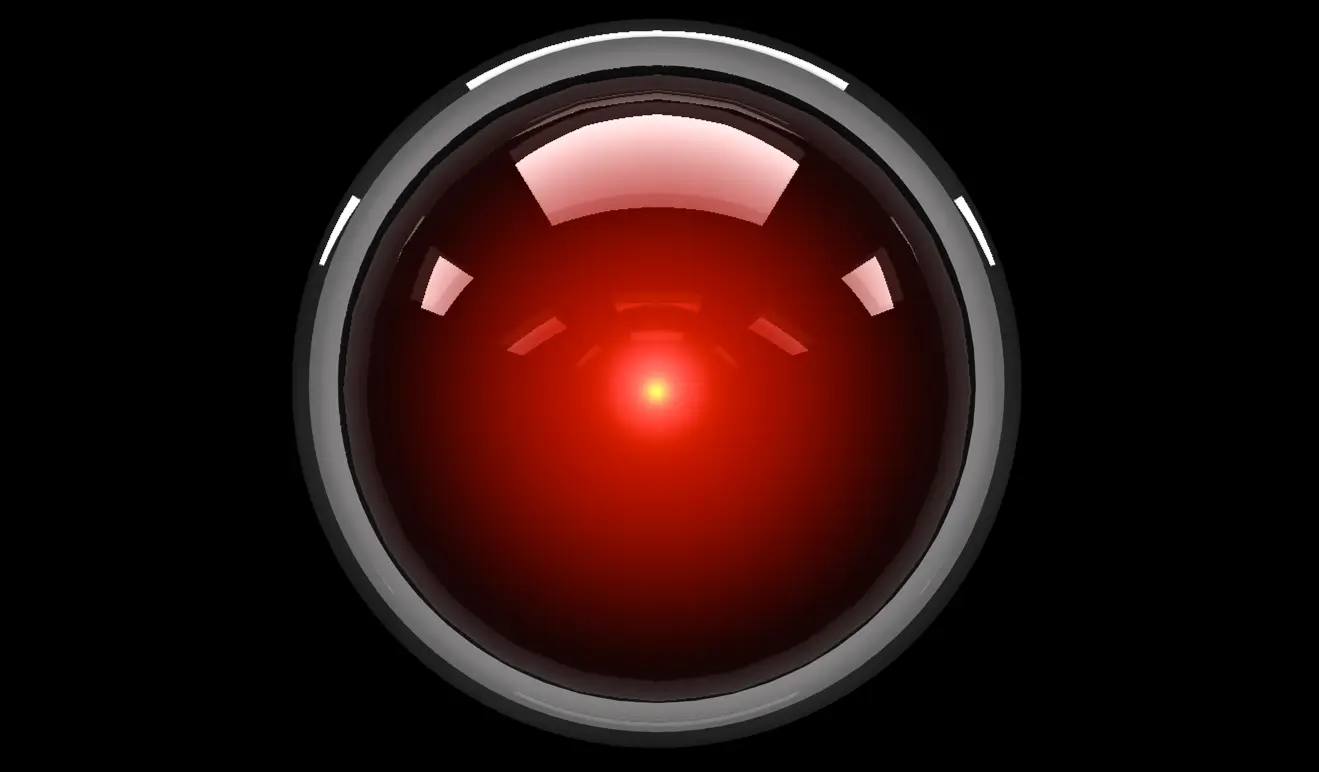

4 million years ago, the Black Monolith awakened the intelligence of the monkeys. In 1999, a second Monolith, found beneath the lunar surface, sends a radio signal towards Jupiter. The Discovery crew investigates the mystery. During the expedition, the onboard supercomputer HAL-9000 kills the crew members. Surviving cosmonaut David Bowman near Jupiter is sucked into a mysterious wormhole…

Another film, another controversy, another delight of some and indignation of others. A work considered groundbreaking in the history of science fiction cinema, groundbreaking in the way of narration, in the production of special effects, in the use of music, in looking at humanity, in virtually everything. Three years of production, a budget of $10.5 million, 205 shots with visual effects, 0.5% of the footage in the finished film – these figures only testify to the production scale of this unprecedented spectacle. Studying the meanders of humanity on the example of closed, strictly characterized micro-communities, Kubrick this time looked at man as a species from a virtually divine perspective (or… from his own).

By ordering an alien, unnamed and incorporeal driving force to make subtle interventions in the chain of evolution, he traced the history of humanity from its birth to the next, seemingly inaccessible stage of development. Only he could undertake such an audacious creative project. Not counting, of course, SF writers, for whom the idea of a top-down plan for human civilization was a daily bread. It was there that Stanley Kubrick found his starting point in the 1951 short story The Sentinel by the British writer Arthur C. Clarke. He invented the radio beacon discovered by man on the moon. Finding it informed the Aliens that humanity, liberated from Earth’s gravity, passed the technological exam. Literature ended here. For Kubrick, it was a starting point for considering the mental condition of humanity as it heads to meet its creators.

Will those who 4 million years ago placed the Black Monoliths among African monkeys and under the surface of the Moon, be interested in further shaping Men in their own image and likeness? Although not, Kubrick was interested in the problem from the other side of the barricade – will humanity, like mentally stimulated apes, still be able to discover the mysteries that surround it? Will technological progress go hand in hand with the primal cognitive desire, and will the self-confident Men, lazily celebrating his own peace among technical toys, still cherish his childish wonder at the Universe?

Stanley Kubrick seems to answer these questions in the negative. And it is hardly surprising as he is a great ironist, mocker and merciless exposer of human imperfections after all. This idea, in a nutshell, is solved by the most famous editing cut in the history of cinema, constantly cited as the shortest history of mankind – a bone thrown in the air by Moonwatcher suddenly turns into an even white, very similar in shape spaceship, continuing the path of fall. Two tools that are four million years apart, both serving the same defensive or offensive function. Both fall down the frame. So basically nothing has changed. Man in Kubrick’s view is still a primitive animal, although only monkeys had something that could be called a life instinct. The man of the space age, dependent on the expensive toys around him and trusting in his own safety, is just an empty shell that the aliens powerful as gods quickly take from David Bowman, turning him into a Star Child, the next level of controlled evolution.

It is no coincidence that it was 2001: A Space Odyssey that Kubrick especially earned the opinion of a cool, cerebral, even dehumanized director. After all, it is here that the only character equipped with human qualities is a faceless machine, the HAL-9000 supercomputer. Bowman and Poole, the main crew of the Discovery ship heading towards Jupiter, are so devoid of emotion that it doesn’t really matter to the viewer what happens to them. Same with the people on the Moon. On the other hand, HAL’s famous “killing” sequence, that is Bowman’s methodical shutdown of his logic circuits, is not only one of the most famous moments of this masterpiece. It is also a moving, almost the only show of true emotions in this film, all the more unusual because we are not dealing with a living being in the conventional sense of the word. All you can hear is the monotonous voice of Canadian actor Douglas Rain, calm until the very end.

And yet – Kubrick’s satanic ability to turn black into white directed the viewer’s emotions towards the machine, without really caring about the fate of the other Discovery crew members killed by him in hibernation. The death of humans is just subtitles, and the death of artificial intelligence is a plea for mercy. The archetype popularized by Frankenstein (continued also by Stanislaw Lem) speaks of the punishment of human pride, which led to the creation of a being mentally equal, or in this case standing above the regressive, Kubrickian Man. A man who – to put it simply and brutally – was too impotent for such an act of creation.

Regardless of its bold, theological references and pessimistic overtones, 2001: A Space Odyssey was quite a shock for the audience of AD 1968. Unlike his previous films, this time Kubrick bet on the cinematography. Of the 139′ screenings, only 40′ included spoken lines. The rest is a splendid visual poem impressing with the elegance of the frames, which – according to Kubrick – was not about a temporary effect, but rather about evoking emotions and impressions in the mind of the viewer, the unambiguous interpretation of which was out of the question. The moral, religious, mystical, philosophical and visual charge of this peculiar paraphrase of Homer’s Odyssey was intended to influence the subconscious, and most questions were to remain unanswered. Kubrick and Clarke, as the authors of the script, assumed it this way and it is impossible to deny their consistency in multiplying interpretative tropes.

Their journey through the history of humanity still has the intensity of communing with a work so perfectly resisting easy rules, like the Black Monolith invented by them. The use of classical music in a way rather associated with dancers in a ballroom is amazing. After all, spaceships perform a kind of dance in the void, carrying motionless people on board (another point for Kubrick and his vision of a mentally dead world of the future). Kubrick originally engaged the composer Alex North, whom he met on the occasion of Spartacus, but his (quite traditional) illustration had never been used in the film, in favor of works of classical composers used at first only as a working piece. He based his clockwork montage on it, subjecting the viewer to the hypnotic effect of majestic images of the cosmos, which cinema had never seen before.

A great film was expected from Kubrick, but 2001: A Space Odyssey was a spectacle whose visual, intellectual and narrative exceptionality no one even dared to suspect. Every aspect of this masterpiece put all the extravagances that the luminaries of world cinematography had tried so far to the wall. From the premiere show on April 2, 1968, which began at 8:30 p.m. in the Cinerama hall of Loew’s Capitol Theater in Washington, D.C., 241 people left before the end of the projection. Most of them were old heads of various levels of production at MGM, not so much surprised as pissed off by the incomprehensible, confusing story with no beginning or end, without a solid plot, acting creations, action, attractions, dynamics and women. The end of the era of Kubrick and his bizarre extravagance for heavy Hollywood dollars was loudly proclaimed.

Mentally devastated, Kubrick managed to throw out only 19 minutes of the most sluggish scenes and after four days made a re-premiere. Meanwhile, in the first week of screening, 2001: A Space Odyssey caused a siege of cinema halls. Kubrick’s demolition of existing ideas about the feature film unexpectedly delighted young people, for whom the film was a manifesto of generational thinking (except for the drug-fueled hippies, for whom the famous journey to another dimension sequence was completely literal). Even the Catholic circles that attacked the director after the premiere of Lolita received 2001: A Space Odyssey with unexpected enthusiasm and respect. A year later, the director received the only Oscar in his career, awarded – ironically – not for an outstanding achievement as a director or screenwriter, but for the visual effects, which he was the designer and main director of, astonishing in their perfection and scientific verism. Other nominations went to Kubrick and Clarke for screenplay, Kubrick for directing, and Anthony Masters, Harry Lange and Ernest Archer for production design. The film ended with a view of the Star Child’s face. Kubrick’s next masterpiece will also begin with a face view…