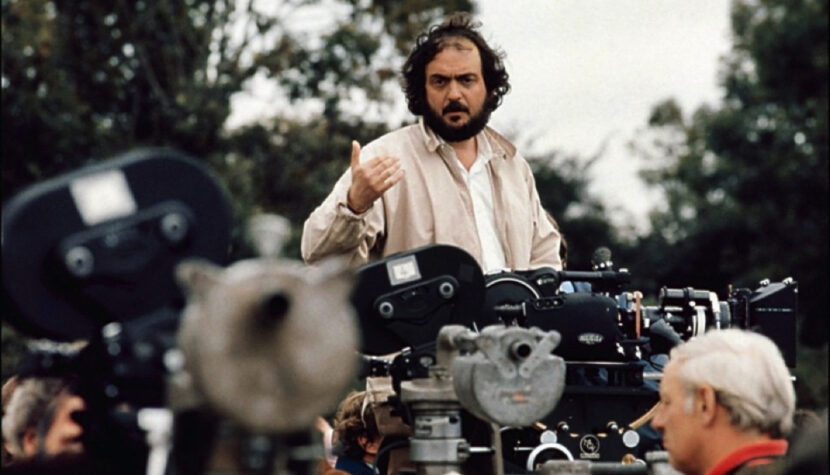

Full filmography of Stanley Kubrick, cinematic genius

“So Steven Spielberg died and went to Heaven. Archangel Gabriel greets him at the blue gates and says, “God loves your movies. Make yourself at home here. I will fulfill your every wish.” Spielberg replied: “I’ve always wanted to meet Stanley Kubrick. Can you set us up?” Frustrated Gabriel replied, “I can’t really do that for you. Stanley doesn’t want any meetings. I’m sorry.” Suddenly, they both see a bearded man in an army jacket riding a bicycle. Spielberg yells, “Look, it’s Stanley Kubrick! Can you stop him?” And the Archangel Gabriel whispers, “It’s not Kubrick. It’s a God who thinks he’s Kubrick.” Kubrick loved this joke.

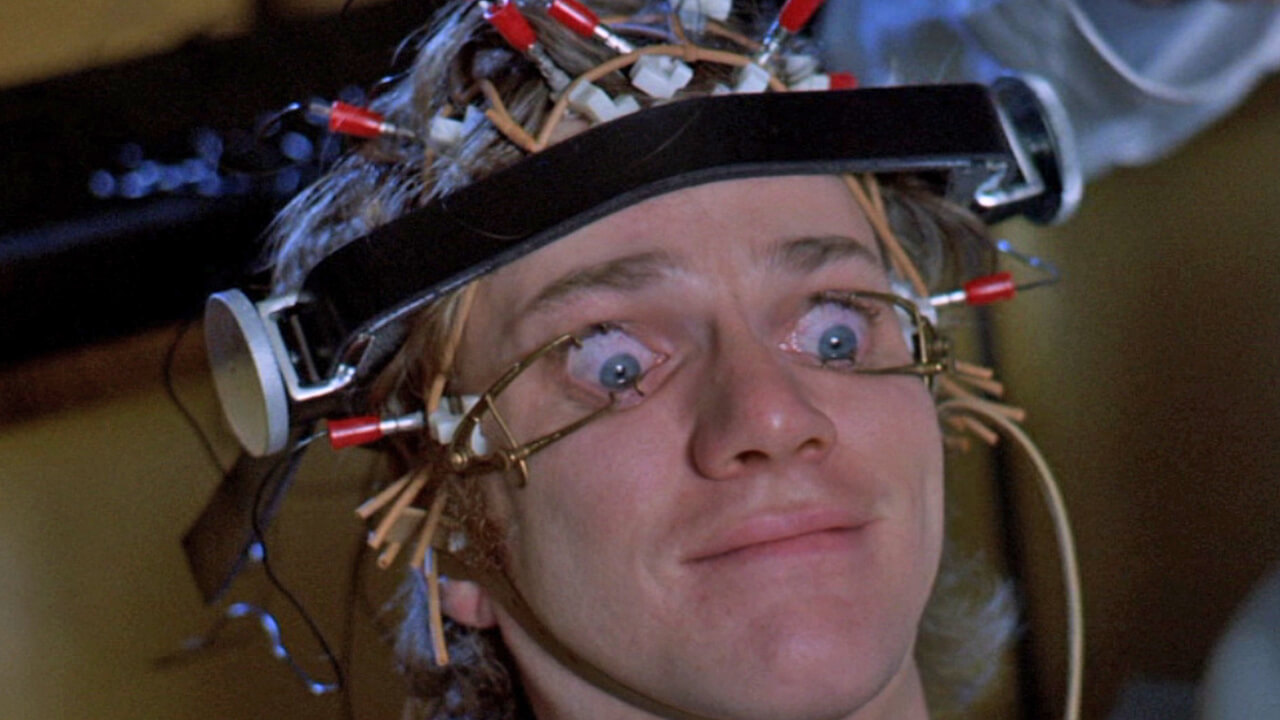

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Alex’s gang divides their time between drugs, fights, robberies, rapes and listening to Beethoven’s music. After murdering the Cat Lady, Alex is caught and jailed. In order to get out of prison faster, he undergoes a brutal social rehabilitation experiment. After his release, Alex, conditioned to violence, encounters people he previously hurt…

Kubrick’s films cannot be brought under one style, let alone a genre. The director’s holistic approach has always left the speculations of viewers and critics far behind. After elevating the SF genre to the rank of Art, Kubrick again made a thematic switch, focusing on the figure of Napoleon. A brilliant director versus a brilliant leader. As luck would have it, at the same time, i.e. in the late 1960s, the Russian director Sergey Bondarchuk, seasoned in large-format historical and battle cinema (his several years of filming War and Peace in its entirety lasted over 8 hours), made a war epic for Dino DeLaurentiis Waterloo with Rod Steiger as Napoleon. The film failed at the box office, which was reason enough to turn off the money for a similar project by Stanley Kubrick.

It was little consolation that Waterloo writer Harry A.L. Craig was credited as H.A.L. Craig. Far-reaching plans to shoot large battle scenes in Romania with the participation of several thousand extras, several years of preparation, hundreds of pages of documentation and bibliography were definitely thwarted, as was Jack Nicholson’s performance in the title role. Some sources also cite information about an unrealized project, tentatively titled Blue Movie. The thing was supposed to be about a film director who, at the height of his popularity, decided to shoot a regular porno with an authentic acting couple. Screenwriter Terry Southern was keen on the idea, turning it into a short story. But one day the script fell into the hands of Christiana Kubrick, who, disgusted, told her husband that if he filmed such a disgusting thing, she would stop talking to him. It was 1970.

Then Kubrick remembered the 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange by the British writer Anthony Burgess, which Terry Southern had suggested to the director while working on Dr. Strangelove. Despite earlier plans for the film (Mick Jagger bought the rights for $ 500, and he wanted to cast colleagues from the Rolling Stones as Alex’s buddies), rumors about the names of directors (Ken Russell, Tinto Brass), it was the appearance of Kubrick that led to the filming of this brutal story, taking place up in the near future.

The bizarre title A Clockwork Orange referred to a language from Malaysia (where Burgess spent several years) in which the word “orang” meant man. So the title meant “mechanical man”, the programmed person Alex actually became by the end of the novel. Burgess, who is fond of linguistic eccentricities (he invented the abstract language of primitive people in the film Quest for Fire), left the title in a form understandable to the English-speaking audience in a somewhat bizarre way. And so it remained, although if not for Kubrick’s screen adaptation, the novel would be a legend, understandable only to fans of the dystopian variety of science fiction literature.

The theme itself was for the director a dream illustration of the problem discussed in previous films. Power versus the individual, the limits of freedom defined by legal regulations, joyful banditry opposed to official brutalism. Kubrick, in a record time, for ridiculously little money (just over $2 million), shooting mainly in natural locations and interiors, within one year, wrote, shot and edited a masterpiece in which, once again and deliberately, placed many important questions.

The cruelty of Alex’s gang, their drug séances and fights, Kubrick presented in a light, visually exciting form, where the negation of violence is questioned by the way it is presented. Gang fights and Alex’s sadistic visions (the shot of the hanging bride is taken from Cat Ballou) is a spectacle full of the purest film magic, impressive with ballet beauty. The brutal attack on the writer’s family, ending with the rape of his wife, appears to the stunned viewer as a music video for Gene Kelly’s cheerful song Singin’ in the Rain from the musical of the same name (the choice of this particular song was prosaic – Malcolm McDowell did not knew any other song by heart).

Suddenly, after Alex is unexpectedly caught and sent to prison, the tone of the film changes drastically. Instead of a joyful ballet of violence, dressed up in action scenes perfectly edited to classical music, the subject of the film finally acquires the gloomy colors of a social drama, which A Clockwork Orange has been from the very beginning. But a complete surprise, though not for fans and analyzers of the director’s work, is the tone in which Kubrick gives something that should be obvious in the first part of the film. Alex raped and robbed, so he should be punished as an example so that the so-called social justice has been done. Nothing of that!

Rehabilitation, which consists in watching scenes of violence in order to extract from Alex an animal reflex of repulsion, appears as rape on an individual, all the more ruthless and terrifying, because it is done in the majesty of the law. The director’s trick quoted above, consisting in effectively persuading the viewer that good is bad and evil is good, reached the apogee of intensity of this opposite message here. In the first part of the film, looking at the victims of Alex’s gang, the viewer is involuntarily on his side. When released, reprogrammed Alex becomes an easy target for his former victims, we also keep our fingers crossed for him to get out of any, even the worst, situation, although the lashes he received from bums and former colleagues should be perceived as part of penance for previous sins. Kubrick wrote the screenplay based on the American edition of A Clockwork Orange, from which the publisher removed the final chapter dealing with Alex’s return to society. After writing the script, the director came to the missing chapter, but Kubrick preferred his own bitter finale of the film, in which evil is an inalienable part of humanity, not a passing whim of youth, as Burgess intended.

Stanley Kubrick once said that without Malcolm McDowell, the film probably would not have been made. Indeed – it’s hard to imagine Alex without the superficiality and talent of McDowell, who later never had the acting opportunity of equally great intensity. Alex’s characteristic belches are Kubrick’s unanticipated acting contribution by McDowell, who was able to perform this unpleasant physiological effect practically on cue. Kubrick recorded the entire Alex’s off narration personally, using a Nagra tape recorder, within two weeks. But Malcolm McDowell only got paid for a week’s work, as he spent half the time playing ping-pong with Kubrick (like Quilty and Humbert in Lolita), who just as willingly deducted it from his paycheck.

Alex’s snake was not inserted into the film until Kubrick discovered that McDowell had a terrible fear of reptiles. In the scene of Alex walking around the future bookshop, Stanley Kubrick appeared on the right side of the frame, with his back turned to the camera, together with Katharina, his wife’s daughter from her first marriage. The director treated Alfred Hitchcock’s hobby in a completely different way, avoiding appearing in front of the camera at all. He actually did it only here, because in one of the scenes of Full Metal Jacket only his voice can be heard in the phone receiver. In the aforementioned scene, when Alex stands in front of the music stand, the cover of the soundtrack to 2001: A Space Odyssey is clearly visible.

While we’re on the subject of music, it’s worth dwelling again on the delightful use of classical music. After the triumph of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick elevated the role of film music (not necessarily written specifically for the film) to the rank of an integral part of the narrative. The scene of Alex’s people walking in almost aristocratic slow motion, ending with their very wet humiliation in the lazy rivers of the Thames, is an example of an unprecedented in its perfection translation into the image of a conflict of power. In the scene of the Ninth Symphony listening, Kubrick refined the video clip-like use of Beethoven’s masterpiece. Even in the days of MTV, no great director attempted such a synchronous combination of image and music.

In this field, Kubrick was unrivaled, even editing the opening and closing credits to the music with frame by frame precision (he also did not give up the old-school THE END, crowning the credits). The electronic adaptation of classical music with the premiere use of a vocoder was undertaken by Walter Carlos, a great enthusiast of synthesizers, who underwent sex change surgery a year after the premiere of the film. As Wendy Carlos, she did similar work on The Shining. The director also dreamed of using Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother suite, but the group refused, not agreeing to editing their music. However, in the aforementioned scene in the record store, the cover of Atom Heart Mother is also visible. A Clockwork Orange was the first film in cinema history to be enhanced with Dolby noise reduction.

Despite easily recognizable cinematographic features, Kubrick employed a different cinematographer for each film. As a fanatical admirer and collector of all kinds of image recording equipment, he himself planned each shot with such accuracy that the DP (director of photography) was actually just a physical extension of his laboriously refined lighting and framing concepts. Briton John Alcott (born 1931) worked as the cinematographer on the special effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was only in him that Kubrick gained a permanent collaborator behind the camera for the next 15 years. Making his debut as chief cinematographer on A Clockwork Orange, Alcott and his two camera operators brilliantly captured all the constants of Kubrick’s cinematography: the elegance of superbly composed static shots, the precision of long transfocations and the wide-angle wheelie rides.

In order to subjectively show Alex’s suicidal jump from the window of the writer’s house, the camera was enclosed in a plastic housing and dropped six times from several meters to the ground. A handful of glass remained from the lens, but the camera itself survived the experiment, much to Kubrick’s admiration for the film technique. In the dinner scene at the writer’s house, Kubrick deliberately made several cinematic errors (sudden changes in the distance between the props on the table, the amount of wine in Alex’s cup also changes abruptly) to deliberately confuse the viewer. The later Darth Vader, or David Prowse, who played the writer’s grown-up guardian, terrified of the endless repetition of the physically tiring scene of bringing the writer together with the wheelchair, took Kubrick in a different way. He approached him and asked, “You’re not that Kubrick who shoots everything the first time, are you?” At this point, the crew froze, but Kubrick laughed and ended up taking only three takes, which was a miracle given the way he worked.

Years later, the film still makes a terrifying impression with its timeliness, although the bizarre make-up, fanciful, Chaplin hats and genital pads worn by Alex’s gang are rather funny to the modern viewer. The courage of Kubrick, who was not afraid of dialogues written in accordance with the letter of the novel, is amazing. Anthony Burgess invented thug slang, consisting of mixed English and Russian. The writer placed a small dictionary at the end of the novel, translating such a strange words for the Anglo-Saxon reader as “korova” (meaning cow in Russian, hence “Korova Milk Bar”), or “moloko” (milk).

Adapting the original, Stanley Kubrick gave the unfamiliar viewer no linguistic clues, and yet the film was an amazing box office success (interestingly – in the 1960s, Kubrick did not want to make this film precisely because of the bizarre slang). On-screen violence has never been handled with such mastery and almost subliminal impact. But this time, the on-screen reality of Kubrick’s film moved beyond film fiction. Over a year of showing the film in British cinemas resulted in a reception that its creator could not have predicted. Albion’s thugs found a ready-made manual of violence in A Clockwork Orange. Assaults, rapes, thefts and even murders multiplied, the genesis of which was very smoothly and not necessarily rationally attributed to the film. When the director’s family, enjoying the peace of Britain, began to receive death threats for involuntarily fueling the spiral of violence, Stanley Kubrick unexpectedly pulled the most unprecedented tactical stunt in the history of cinema.

Being at the beginning of cooperation with Warner Bros. which financed and distributed all his subsequent films, demanded that A Clockwork Orange be withdrawn from British cinemas. Warner bosses had to agree, despite the excellent box office receipts, some of the best in the company’s history. Given the choice of short-term money or a long contract with Kubrick that cedes full control of the film to the director, major studio bean counters have chosen the latter. The ban, in place until Kubrick’s death in 1999, was extremely strictly enforced. In the early 1990s, the film was illegally screened at London’s Scala Film Club. When this information reached Kubrick, who lives near London, he reported the case to Warner Bros. lawyers who nearly wiped out recalcitrant movie buffs financially in the course of a lawsuit. For A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick received three Oscar nominations (film, director, screenplay). Bill Butler was also nominated for editing.

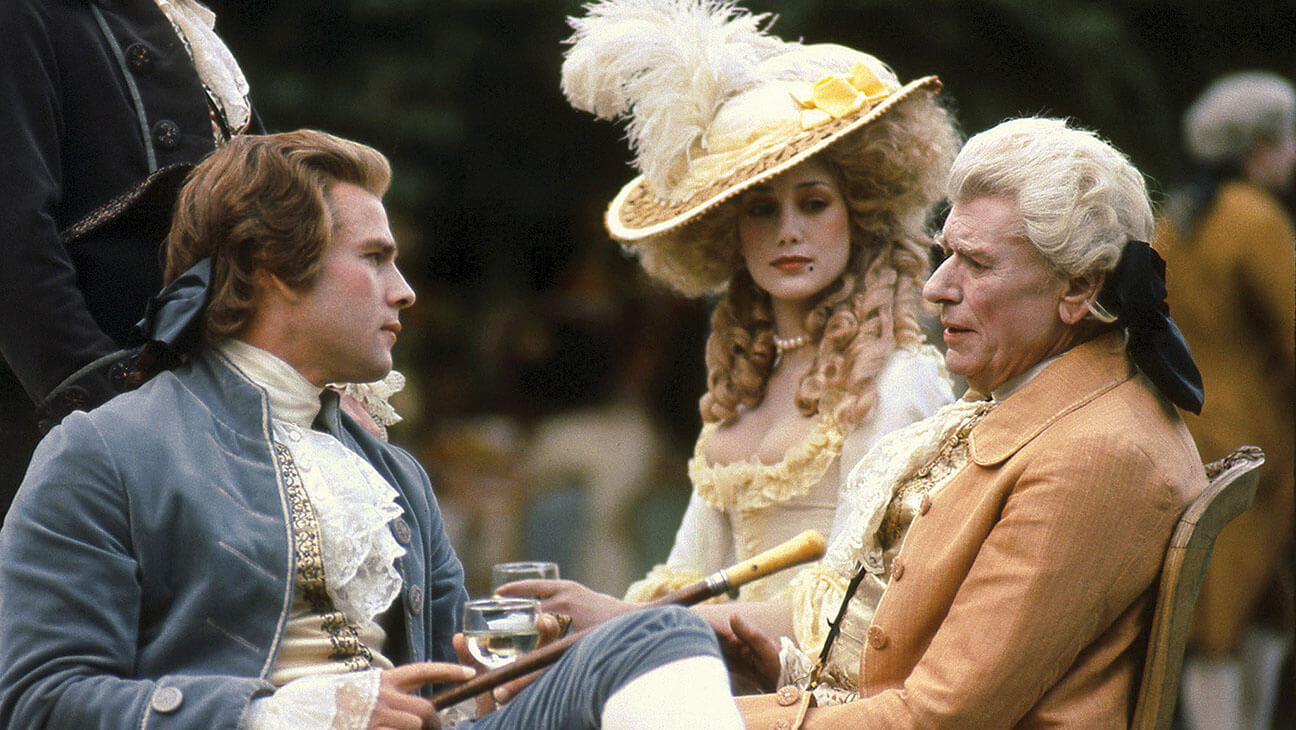

Barry Lyndon (1975)

Irish teen Redmond Barry falls in love with his cousin. When she chooses an officer, Barry kills him in a duel and escapes, successively joining the British and Prussian armies on the fronts of the Seven Years’ War. Meeting his countryman Chevalier de Balibari, Barry escapes from the army. Leading the life of a gambler and playboy, he meets the wealthy Lady Lyndon, whom he seduces, and after the death of her husband, also marries…

It starts out like a Monty Python sketch. An off-screen voice announces that Redmond Barry’s father might have had a long and successful life ahead of him, but things went a bit differently… and then a shot is fired. Of the two opponents dueling with pistols, one falls to a green meadow. Just. Strict, even bizarre, adherence to the norms of the code of honor in the world of conventions of the buttoned up eighteenth-century Britain, became another laboratory for Stanley Kubrick in which he conducted a vivisection of social relations.

Man, no matter if in the trenches of war, on the way to Jupiter, or among the civilization of the future drowned in moral decay, will always be a prisoner of an invisible fortress. At best, it will be a long and exhausting fight, but it will be a fight marked by defeat from the start. The choice of the novel The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq, written in 1844 by the eminent British writer William Makepeace Thackeray (Kubrick originally considered adapting Vanity Fair, the writer’s most famous novel), only seemingly placed Kubrick in a new for him costume drama set in the eighteenth century. The director once said that a psychological novel is best suited for filming, because only then can you focus on coming up with a sufficiently exciting plot when you get a ready-made internal characterization of the characters.

Barry Lyndon is another example of Kubrick’s creative appropriation of someone else’s world in order to play his own chess game in it (The Shining was created on the same principle, for which, as we know, Stephen King threw himself at Kubrick, and not to embrace him). Redmond Barry, renamed Barry Lyndon, is another Kubrickian outsider in an unbearably formalized world. One more red spot that spoils the pure white, although in this case the white was replaced with green, which the director showed literally in several scenes, e.g. on the lake, when the calm color of nature is broken by the sharp red of a huge sail, or on the battlefield.

The world surrounding Barry resembles a clumsy theater full of human puppets. Formalized British rigidity, under which obscene passions are bubbling, living according to the hypocrisy defined by holy rules is observed in this world with exceptional solemnity, beyond the limits of the broadest common sense. Even a military clash with French troops resembles a ritualized parade, all the more poignant and senseless as it is performed under fire, mercilessly and effectively mowing successive ranks of soldiers obediently going to the slaughter. Only Barry can afford the human gesture of taking his commander off the battlefield (practically the same thing Forrest Gump did with Lt. Dan).

Yet there is something irresistibly fascinating about it. The robbing of Barry in the woods by two cutthroats is verbally an oratory duel of politeness. Pistol duels or dialogue exchanges of contentious issues, if we cut them out of their fictional context, look like a beautiful conversation of Oxford professors. Stanley Kubrick has always been passionate about the language of the characters, the limits of the verbalization of emotions that can be reached. It is also impossible not to notice his characteristic irony, emphasizing the absurdity of the presented world. In Dr. Strangelove, the military language of the dialogue stood in obvious opposition to its meaning. Here, this role was partly taken over by the nameless narrator, whose dry, chronicler’s additions from behind the scenes of the story on the screen often conflicted with the anointed solemnity of the ceremonies filling the lives of the characters (in the novel, Barry himself was the narrator). For example, in the aforementioned battle scene – before the first shot was fired, the narrator dispassionately announced to the viewer that this skirmish was not even recorded in the history books.

The corpses are plenty, but it is impossible not to get the impression that these soldiers were already dead when they were alive. The whole world, against which Barry’s activity, his foresight, succumbing to feelings, emotions, lusts, moods, moments that lead life astray, appear as a glorious praise of humanity in a perfectly furnished wax cabinet.

In the history of cinema, there are several period films that look like an authentic film record, made on the spot at a time when the invention of the movie camera was not dreamed of by the greatest visionaries. Such was David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980), and so was Barry Lyndon, five years earlier. This film is considered the most visually beautiful picture of all time. Some people don’t like the word “picture” when referring to moving pictures, but in the case of Barry Lyndon the word takes on a very specific meaning. Each frame of this masterpiece is a finished picture, painted with natural light and framed in a film frame composed by Stanley Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott.

The Irish, German and English outdoors are so captivatingly beautiful, so transparent that there is even a suspicion of the use of spectacular matte-painting techniques (elements of the frame replaced with paintwork on the glass). None of these things! It is a miracle to capture clear and clean landscapes stretching to the very horizon, over which picturesque cumulus clouds lazily flow, shot in capricious, island weather conditions. The explanation for this miracle is somewhat simple, because the filming took two years. The visual mastery is breathtaking, all the more so since Kubrick and Alcott successfully performed the above-mentioned complete reconstruction of the era. They shot in natural locations, interior scenes were also shot in real historical locations. Not a single shot was recorded in the sound stage.

Costume designer Milena Canonero dressed the actors in authentic, mostly exaggerated costumes from the period, and what could not be bought back or rented from museums and collectors, was sewn with extreme precision and faithfulness to the originals.

Much ink has been written about the light used in Barry Lyndon and many websites have been filled with it. The issue is puzzling as the cinematographers themselves speak with a sneer about faint, and if so, cheap compliments from critics large and small, limited to perfunctory slogans about beautiful photos (usually in the context of trivial sunsets or spectacular camera travel). Against this background, the visual side of Kubrick’s film shines with a rare glow of well-deserved and competently commented splendor. The work of a cinematographer is primarily about controlling the light, most often artificially produced. Filming outdoors is a gamble, a roulette between art and weather. Barry Lyndon is an unprecedented immortalization of the world, illuminated only by the Sun during the day, and dispelled by candles at night. John Alcott used the film’s spotlights imperceptibly in the daytime scenes. Where natural light thwarted the plans of the filmmakers (clouds, rapidly falling dusk), the cinematographer painstakingly reconstructed the natural illumination using his own lighting equipment.

The famous night scenes, with actors playing only under candlelight, managed to become a legend no less than the film itself. Kubrick, in his frenzied perfectionism, excluded the use of artificial light, and being an oracle in matters of photography, he looked at Zeiss lenses, specially prepared for the cameras used by NASA during the Apollo missions. These were the fastest known lenses (i.e. allowing the fastest possible exposure of the negative with the smallest possible light, in other words allowing the maximum opening of the aperture), and only such ones guaranteed the appropriate brightness and contrast of the image when filming among candles. The problem was that such lenses as camera equipment could not be attached to Mitchell BNC film cameras (all other shots were shot with the Arriflex 35BL camera, also used by Alcott on The Shining). Ed DiGiulio, director of Cinema Products Corporation, solved the problem himself through a complicated adapter.

Another problem was the viewfinder of the Mitchell camera, through which the candlelit scene was virtually invisible to the operator. Here, a viewfinder disassembled from an old camera used for the first films in Technicolor was used. These scenes were shot at f/0.7, the highest aperture ever used in a feature film. With such little light, the depth of field practically did not exist, and the focal length was determined to the millimeter by means of a video preview coupled with the camera. This explains why the actors in the “candle” scenes did not make any sudden movements, they hardly moved at all.

It was virtually impossible to focus on an actor in motion in such low light. By the way, this technical detail perfectly matched the mood of the whole film, and the British phlegm, so ruthlessly exposed by Kubrick, merged with the forced stiffness by candlelight. Ironically, it wasn’t until after the film was finished that the labs started producing negatives that would allow proper exposure in such low light without resorting to the tricks of ultra-fast lenses.

Another unusual operator’s device, unheard of in costume cinema, were the transfocator rides repeated many, many times. Each one began with a close-up of a detail important for a given scene, so that after a dozen or so seconds all the details became just a minor element of the beautifully composed general plan. As if by this simple operator maneuver, Kubrick wanted to say that all human follies are in fact so small and unimportant that all it takes is a slight change of perspective, the ability to look wider at the majestic nature of the Irish hills, to lose interest in something as unimaginably small as Man. This divine perspective was already implemented by Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

A glance at the eighteenth century also leaves no illusions as to the perception of the human condition. Kubrick, with his demiurgic obsession, was able to transpose entire complex philosophical problems into concrete film with a single shot, and sometimes even a single cut.

The precision of the use of classical music in previous films, Kubrick brought in Barry Lyndon to mega-perfection. The narrative, led by brilliant images, once again gained a dazzling rhythm of classical music pieces, selected with incredible care, taste and elegance. The result that film music composers can achieve by creating original music for a previously shot and edited picture, Stanley Kubrick achieved with incomprehensible precision by means of works already known and written in conditions having nothing to do with the film. Thanks to their plot anchoring and precise cutting of the image to the rhythm, Kubrick achieved a full fusion of meaningfully saturated images with the desired pace and character of the story. Just amazing.

The scores seem to have been written specifically for specific scenes, such as the Hitchcockian suspense (and edited for 42 days) scene between Barry and his stepson Lord Bullingdon. The nerve-wracking duel with its unhurried pace, more for characters than for guns, was illustrated with a very bassy version of George Frideric Handel’s theme, with string counterpoints that appears in several variations. On the other hand, the use of the beautiful classic Irish melody Women of Ireland performed by The Chieftans is delightful. The three-hour screening of Barry Lyndon, contrary to prejudice against lengthy costume dramas, is watched on the edge of the chair.

In terms of the genre, the absolute genius of Barry Lyndon was probably only achieved by Milos Forman in Amadeus. But the audience at the time was not too enthusiastic about the film. Barry Lyndon was recognized by the American Film Academy with Oscars for cinematography (John Alcott), set design (Ken Adam, Roy Walker and Vernon Dixon), costumes (Milena Canonero and Ulla-Britt Söderlund) and adaptation of the music by Leonard Rosenman, but it was Forman and his One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest that took away the Oscars for film, direction and screenplay, categories for which Kubrick was also nominated. The director invested 11 million in cinema, which was just becoming a thing of the past, replaced by modern thrillers, horrors and disaster films. It was a bad omen that two years of production were halted twice due to ever-increasing costs. The era of Spielberg’s blockbusters, lasting until today, began, in which there was no place for such sublime auteur cinema, even the most brilliantly photographed and narrated. Kubrick took note of this…

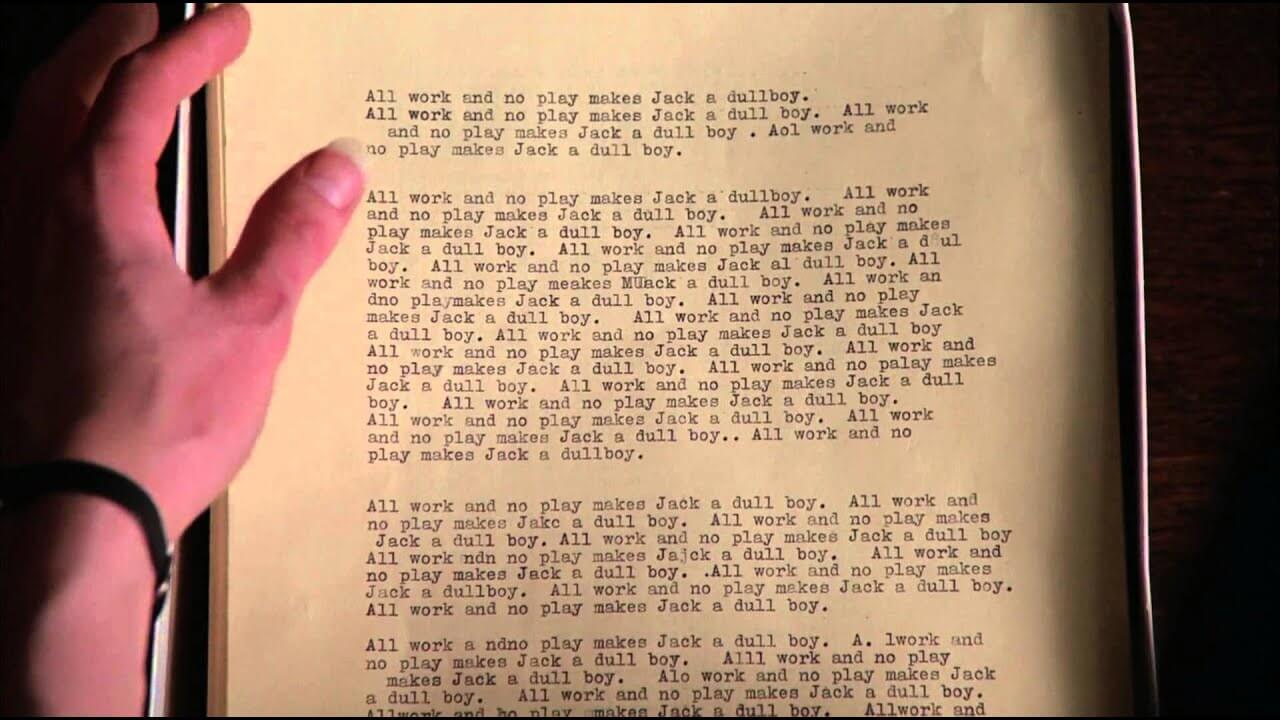

The Shining (1980)

Writer Jack Torrance, his wife and son move to the Overlook Hotel in the mountains as a caretaker. The intention to write a novel in the silence of an abandoned building increasingly fades into the background as Jack’s paranoia is growing. His son Danny experiences terrifying and bloody visions of the girls who were murdered many years ago by their father and former caretaker, Grady…

With the box-office failure of Barry Lyndon fresh in his mind, Kubrick decided to explore the commercially safer horror genre, in which he appreciated Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist. In 1977, he became interested in Diane Johnson’s The Shadow Knows, but at the same time John Calley, head of production at Warner Bros. sent him a copy of Stephen King’s newly published novel The Shining (the title is taken from the phrase “We all shine on” in John Lennon’s song Instant Karma).

While searching for good adaptation material, Kubrick reworked heaps of horror novels, but he did so at lightning speed. According to his secretary, for several hours, at intervals of a few minutes, Kubrick’s office heard a dull crack. It’s another book smashing against the wall. Kubrick only read the beginning. If a novel did not interest him from the first paragraphs, he would throw it away. Suddenly, the pounding outside the door stopped. Kubrick got to King’s book, which surprised the writer himself, as he considered the beginning of The Shining a slow and boring prelude to the rest of the plot. Stanley Kubrick saw something in The Shining that he didn’t find in other horror novels, and that finally stirred his ever-exploring mind. He described it as “a balance between psychological and fantastical aspects, in which the supernatural can initially be explained in terms of psychology and even psychiatry; and when the irrational horror reveals its truth, the viewer accepts it without batting an eyelid.”

Kubrick was also attracted by the ability, unavailable in realistic prose, to translate plot twists with the help of the fantastic element. Stephen King offered to write the screenplay, but Kubrick – of course – decided to do it himself, hiring the theoretically prepared Diane Johnson (whose novel he had previously rejected) for three months as co-writer and consultant to every Kubrick scare patent.

The director wove standard elements of horror literature and cinema into this story about the madness of the human spirit: lack of alcohol and cabin fever make Jack a madman, similar to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The werewolf motif is revealed in the ending, when Jack is running around with an axe and howling like a wild animal. Looking at the empty bar, Torrance complains that he would give his soul for a glass of beer, and suddenly, like the devil, the bartender Lloyd appears, offering a drink. Black magic is present here in the form of the gift of shining; not to mention the haunted house. However, this is only a surface, a facade, playing with the convention.

From the genre leitmotifs of horror cinema, Kubrick sewed his next chapter of the story about human regression, about what will remain of the bans, orders and obligations consolidated in the course of social training, confronted with the demons of the soul released in an extreme situation. This time the director did not need a broader social background, it was enough to take a few characters out of it and throw them into the apparent emptiness of the Overlook Hotel, cut off from the world. Mel Brooks once joked that all he needed to make a good movie was a camera and six Jews. Taking into account the proportions, Kubrick was satisfied with more or less the same.

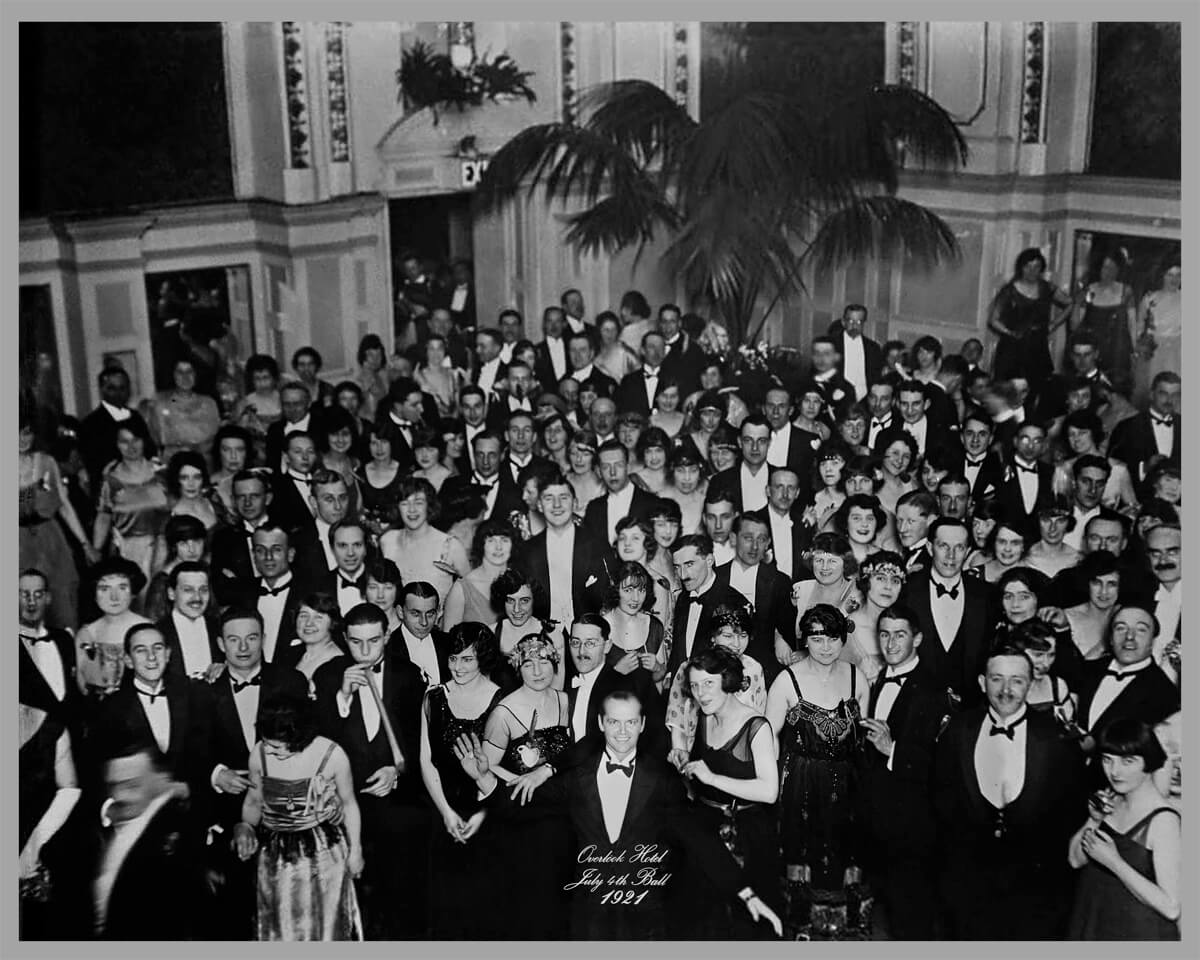

First of all, the motif of the mirror dominates here: splitting, dualism, as well as symmetry and balance, which is repeated in many variants. Janitor Grady is two versions of the same person. One is Charles Grady, the previous caretaker who killed his entire family (including TWO daughters) with an axe. The other is a waiter from 50 years ago, Delbert Grady, who however tells Charles’s story as if it were his own (with an obvious British accent). Jack Torrance becomes the heir to Grady’s gruesome plan as the story progresses, and the finale reveals Jack in a 1921 photo. Danny Torrance suffers from a specific split personality that he calls Tony, “the little boy that lives in his mouth.” Duality also dominates in the visual layer. The very first shot shows the bleak landscape of the Rocky Mountains reflected in the smooth depths of the lake. In the breakfast scene, Jack’s face is reflected in the mirror. Looking at his own reflection in the bar mirrors, Jack sees Lloyd the bartender. Thanks to the mirror image, Wendy identifies the word redrum as murder.

The redrum itself phonetically refers to the “red room”, i.e. the red room, probably the one with the number 237. The red room has its “color brother” in the form of the gold room, i.e. the golden ballroom. Also thanks to the reflection in the mirror, Jacek receives a real image of an old and rotten woman, previously in a young and beautiful form. Many decoration elements (bathrooms, halls, corridors, elevator doors) were built and framed with almost mirror symmetry. Finally, the labyrinth itself is a translation of the mental mess in Jack’s head into a stage design. And in the same labyrinth, Danny leads Jack astray, following his own footsteps, i.e. duplicating and contradicting it at the same time.

The Shining is an arch-genius, showpiece performance by Jack Nicholson, for whom King harbored one of many grudges against Kubrick. The writer explained that the Jack in the novel does not physically resemble a madman at first, and his descent into the abyss is slowly dosed to the unsuspecting reader. On the other hand, Jack Nicholson’s face alone, supported by his demonic smile, leaves no doubt as to the character’s development from the very first shot. King saw Martin Sheen, Jon Voight or Michael Moriarty in the role. His wishes can be summed up briefly – he was wrong not to take into account Kubrick, who marginalized the plot of Jack Torrance’s alcohol addiction.

His madness was supposed to flow from the dark side of humanity, not from an open bottle of Johnny Walker. Although he did not even receive an Oscar nomination for his masterful performance (which was then won by Robert De Niro for Raging Bull), Jack Nicholson created a fascinating portrayal of the awakening beast on the screen, as fascinating and terrifying as it is deeply moving in its tragedy. Torrance joined Kubrick’s gallery of characters fighting for their own independence, the most literally understood freedom and liberation from the shackles of social confinement. Fighting and losing.

Kubrick’s pessimism took over again. There is no escape or way out of the labyrinth, in the nooks and crannies of which the red-hot madness will lose to the all-encompassing snowy whiteness. As critic Marc Salmon wrote: “Jack will die amidst the whiteness that will defeat him with its excess of violence and will freeze, stiffen, like rigorous social laws. Rigorousness is introduced, society has won, but man has died”. Again, the opposition of white and red, played in The Shining more often than in any other Kubrick’s film. If you look closely, almost every scene contains some red element of decoration surrounded by white, as in the scene of Torrance’s conversation with Grady in the toilet (by the way, Kubrick likes to place important scenes in this type of establishment).

A funny story is connected with the famous scene of breaking the door with an axe. Jack Nicholson had once been a volunteer fireman, and the first time he had smashed a fragile door prepared by decorators without any problems. In order for the scene to make any sense at all, several pieces of much stronger doors were prepared. The famous “Here’s Johnny!” was improvised on set by Nicholson himself, imitating Ed McMahon from NBC’s The Tonight Show, which introduced Johnny Carson’s performances. During production, the script was changed so many times that Jack Nicholson finally gave up on the whole thing, focusing only on the lines he had to make on a given day of shooting.

Since 2001: A Space Odyssey, small acting cameos by Vivian Kubrick have become a tradition. In Barry Lyndon she appeared among the children entertained by an illusionist, while in The Shining she can be spotted near the bar in a black dress among the guests in the golden ballroom. She also made the 35-minute documentary Making The Shining, present on the DVD release. The apparition with the bloody head saying “Great party, isn’t it?” was played by The Shining’s second editor Norman Gay. During casting, Kubrick played David Lynch’s grim debut fantasy, Eraserhead, to get them in the mood. For obvious reasons, the screening spared only Danny Lloyd, whom he treated with extreme care, regardless of the rigorously observed regulations regarding the amount of time a child spends on the set of a film. He steered him loudly on set during shots, and for example, in the encounter with the ghosts of Grady’s daughters, Danny had only Kubrick in front of him (except for the first shot in that scene). The rest was handled on the editing table, combining his shots with shots of the girls shot separately. The little actor only found out long after the premiere that The Shining is a horror film.

Due to the genre of the film, Danny was not played by Cary Guffey, whom Kubrick saw in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Cary’s parents categorically refused to have their child in the horror film, so Kubrick was forced to choose another boy from 5,000 applicants (or rather, his assistant Leon Vitali and his wife, who auditioned all the children). The director had another skirmish with censorship, and all because of the phenomenal shot in the trailer with blood pouring out of the elevator (three doubles, nine days of production). Censorship could not allow the trailer with the presence of blood to be widely distributed, so Kubrick used a ruse, telling the guardians of screen morality that it was not any blood, but rusty water. He made it.

Despite being set in the Overlook Hotel surrounded by the Rocky Mountains, Kubrick shot almost everything in the vicinity of his British estate. He sent only a few camera crews to the US, including one led by Greg MacGillivray, which produced some of the greatest helicopter shots in the history of cinema for him. Actual photography began on May 1, 1978, and continued until April 1979. The budget was approximately $19 million. The facade of the film’s Overlook Hotel was built in the car park of EMI Elstree Studios in Borehamwood, London, closely following the appearance of the authentic Timberline Lodge in Mount Hood, Oregon, USA, featured in the widest outdoor shots. The interiors of the real hotel differed from the sets by Roy Walker, who designed the Overlook interiors based on the general look of American hotels.

The management of Timberline Lodge showed an embarrassing lack of marketing sense when they asked Kubrick to replace Room 217 in the script with Room 237, which did not exist on their property. They were afraid that no one would want to live in it after seeing the film. Kubrick granted their request. The owners of the hotel did not take into account the movie geeks who would die for the opportunity to spend the night in the apartment with the number from the original script. In the course of replacing King’s ideas with his own, Kubrick replaced the hedge animals with a labyrinth, which was formed on the screen from as many as three sets. The outer wall of the maze was built in the parking lot, its winding interior was erected at Radlett Airport, 5 miles (8 km) away, and the final chase was filmed in separate set in the sound stage, built of the same hedge blocks. Kubrick became so attached to the location of The Shining that in the warehouses adjacent to the halls he created both his personal corner, as well as an archive and, above all, an editing room.

The Shining was put together and sounded in five months here, instead of in the studio’s normal editing rooms. A fragment of this warehouse played a huge hotel kitchen in the film. After the shooting, the decoration of the great lobby went up in flames, which was kind of handy for other clients of EMI Elstree Studios, who had to make a specific modification of the shooting hall anyway, consisting in raising the roof by 3-4 meters. This was the request of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, who supervised the construction of the Well of Souls decoration for Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The worlds of Paths of Glory, A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon owed their extraordinary credibility to the moving camera, which emphasized the authenticity of the places of action. The Shining was almost entirely made in the production halls. In addition, Kubrick conceived of shooting The Shining chronologically, which forced all the sets to be built at once and left for the entire 200-day shooting period. The film illusion was to be born without theatrical tricks and editing masking the change of plan. The camera cart that Kubrick used in previous films was no longer enough. The camera had to gain a mobility unmatched by any previous film.

To this end, Kubrick enlisted cinematographer Garrett Brown, the inventor of the Steadicam, a seamless handheld recording device first used in Hal Ashby’s 1976 film Bound for Glory and the fight sequence in Rocky. Garrett Brown initially wanted to lend Kubrick his toys and train the operator, but after seeing the set at Elstree Hall, he saw an opportunity to be part of something really big, not just from a Steadicam operator’s point of view. This story was to be told with a moving camera and smoothly reach places that a traditional trolley cannot reach. A standard Arriflex 35BL camera was mounted on a Steadicam. Brown was out of shape and in the shots from behind Danny’s bike it was impossible for him to move the camera a few inches off the floor by hand, so a bizarre wheelchair-like trolley was used that Kubrick had already used on A Clockwork Orange.

The one-year shooting period, coupled with Kubrick’s obsession with securing the best possible technical conditions, resulted in constant technological progress on the set. The method of wireless video signal transmission from the Steadicam to the monitor was modernized, a prototype device for remote control of aperture and focus was used, and new Steadicam mounts for various trolleys were constructed. The endless retakes of shots, during which a lot of nuances between the operator and the camera were discovered and corrected, were also significant.

Kubrick was able to have 100 meters of flooring replaced just to make the cart run smoother. The director thought of attaching a speedometer to it for perfect shot repetition, but Brown was concerned that this would affect the stability of the cart, so the idea was dropped. The sense of eerieness of steadicam shots is literally enhanced by 18mm wide-angle lenses, rarely used on such a scale, unnaturally expanding the image at the edges. For the final maze chase sequence, this effect was enhanced by the use of 9.8mm lenses mounted on a lighter Arriflex IIc camera. For Garrett Brown, this sequence was a unique, even in the scale of the entire film, physical challenge. When little Danny retraced his steps, so did Brown, who for the occasion put on special shoes with a small sole, matching the imprint of the little actor’s shoes.

Due to the use of the ubiquitous Steadicam, John Alcott had to solve a number of lighting problems. The light had to come from “natural” sources, which were part of the decoration and visible in the frame in the form of fluorescent lamps, candelabras, sconces and chandeliers. The most spectacular feat was the lighting of the great lobby hall where Jack was trying to write his novel. From behind the huge windows came natural daylight, which – though it sounds incredible – was entirely the work of the crew. Behind the decoration of the lobby, a 25 x 10 meter screen was placed, behind which 860 thousand-watt lamps connected to a set of resistors were mounted on a special scaffold. This was the illusion made by Kubrick. And to think that all this is done so that the viewer does not even think that he is watching a studio simulation of an authentic interior. Some unused helicopter shots by Greg MacGillivray, with Kubrick’s permission, were used in 1982 by Ridley Scott, forced to fit a happy ending to his Blade Runner.

Stephen King’s initial enthusiasm waned after film’s release. Though critics emphasized how Kubrick’s genius translated a mediocre novel into an immeasurably superior film, the writer was deeply displeased: “Kubrick’s film is like a big, beautiful Cadillac without an engine. You can sit in it, marvel at the interior finish, but you won’t move it. Kubrick made a horror film without trying to understand the genre that screams from every aspect of the film.”

King licked his wounds until 1997 when he became the writer and producer of the three-part TV mini-series Stephen King’s The Shining. Here he arranged everything exactly as in the novel, he practically made a mobile version of it, but the viewers brought up on Kubrick’s masterpiece were not impressed. Allegedly, Kubrick considered the idea of killing the entire Torrance family and having them return as ghosts, but King talked him out of the idea. In addition to the well-known two-hour version of The Shining, there is also a rarity in the form of an originally edited film with a running time of 144 minutes. After poor reactions from American critics and box-office results, Kubrick decided to cut 25 minutes. This abridged version, based on a test screening in London, was distributed to the rest of the world and was also released on DVD.

The American theatrical edition also featured an alternate ending (present after the famous photo on the wall was shown) in the form of Ullman’s visit to the hospital with survivors Wendy and Danny. Ullman announces that Jack’s body has not been found, and as he leaves he gives Danny a ball, the same one that had rolled up to the boy in the empty hotel corridor. Kubrick cut this finale out during its first week of screening in the US. It is not even on the currently hard-to-find extended version (I deliberately do not use the name “director’s cut”, because each of the two editions is basically a director’s cut, because edited by Kubrick). An interesting fact is that in the shortened version the names of the two actors (Anne Jackson as the doctor and Tony Burton as Larry Durkin, who rents a snowmobile to Hallorann) were left in the extended version only.

The Shining is listed in the Guinness Book of Records for the most doubles of a scene involving an actor. It’s about the scene at the end of the movie where Wendy climbs the stairs, said to be repeated 127 times by Shelley Duvall. However, there are opinions from people associated with the production of The Shining that nothing like this happened, and the highest number of takes, oscillating around 80, was for one of the scenes with Scatman Crothers in the hotel kitchen. Shelley Duvall repeated the scene with the baseball bat on the stairs about 45 times, mainly due to technical problems with the Steadicam. In turn, according to data from www.imdb.com, the slow close-up of the “shining” Hallorann was filmed by Kubrick more than 120 times. In addition, the director wanted to do about 70 takes of Jack’s killing of Hallorann, but Nicholson’s subtle intervention to be gentle with the 70-year-old Scatman Crothers shortened the creative process by 40 times.

In one of the few interviews, Kubrick explained his murderous approach to actors. Well, expecting a perfect combination of emotions and technique, the actors rarely gave Kubrick both in the same shot. Either experiencing the role killed the substantive preparation, or the acting technique overwhelmed the naturalness. The amount of material shot in relation to the length of the edited film was 102:1, which was nothing new for Kubrick. A very interesting shot of Jack looking at a miniature maze, inside which you can see the real characters of Wendy and Danny, is one of the few examples of Kubrick’s use of special effects. This shot was indeed taken with the miniature upright. In its central part there was a small screen on which, using the rear projection method, a previously shot shot of the actors was projected in the decoration of the labyrinth.

The closing photograph from 1921 was authentic. Kubrick personally took a photograph of Jack Nicholson’s face, which was then manually inserted into the original photograph. The director stated that he would not be able to recreate the authenticity of the people in the picture with the help of make-up extras (although in Barry Lyndon he performed this trick masterfully).

The precedent of 2001: A Space Odyssey, when Kubrick eschewed original music in favor of recycling the classics, was repeated in a less drastic form with The Shining. Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind’s original electronic score has been left in tatters, the most memorable of which was Hector Berlioz’s adaptation of Symphony Fantastic, present in all its musical horror in the opening credits. The vast majority of the film was illustrated with terrifying, mind-drilling sounds from Krzysztof Penderecki’s works (these were original performances performed with Polish symphony orchestras) and works by György Ligeti and Béla Bartók. The embittered women composers, due to legal conflicts, were not even able to release a CD containing their original music (the vinyl original was published only after the premiere of the film in 1980), which was not released until 2005, as part of the Rediscovering Lost Scores publishing house.

At the end, we should add a gloomy “joke”, which was the nomination of Shelley Duvall and Stanley Kubrick for … the Golden Razzie.

The Shining completely fulfilled the basic creative postulate of Kubrick, who simply wanted to scare the viewer, at least taking into account the most external, most obvious aspect of the film. His first and only horror film become one of the best scary movies of all time, although the director himself ironically and perversely admitted that The Shining is a very optimistic film. Why? Well, because since it’s a ghost movie, it means that death is not the end of life…

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

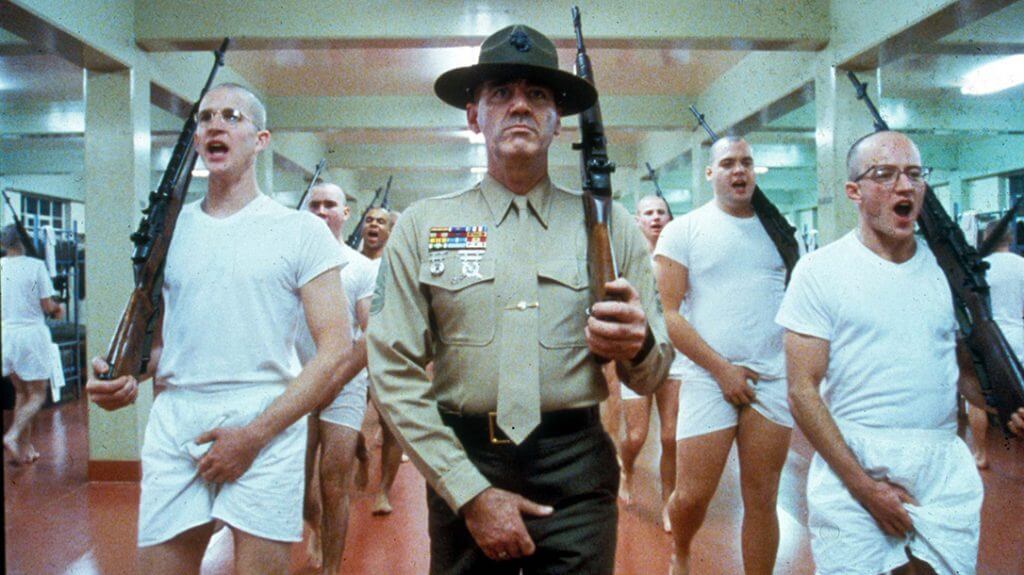

Private Joker is one of the Marine Corps recruits trained by the demonic Sgt. Hartman. Brutal but extremely effective training works even against the clumsy Pyle, who slowly becomes Hartman’s most perfect creation. But Pyle can’t stand the rigors and kills Hartman in front of the Joker. Soldiers find themselves in war-torn Vietnam…

Stanley Kubrick, like any other director, built the visual side of his works with exceptional reverence and credibility. But he seems to have cared equally little about the precise location and temporalization of his stories. Even if the time and place of the action were closely related to a certain historical period, the only thing that mattered was another vivisection of his author’s obsessions: the limits of freedom, madness and humanity. As the critic Terrence Rafferty wrote: “He prefers some misty future, or a distant, completely imaginary past, he prefers scenery that cannot be precisely located. His films, through their artificiality, their original mystery, are located outside of time and, in principle, also outside of defined space”.

Kubrick was fascinated by institutionalized violence, especially in its most natural environment, which is the army. He looked at it closely in Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove and Barry Lyndon. It would seem that the subject of the military was exhausted for Kubrick. Meanwhile, right after The Shining was finished, enjoying the spring peace in his new residence in Hertfordshire, the director met Michael Herr, a war correspondent from Vietnam, author of the narration for Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). Herr introduced Kubrick to the autobiographical novel The Short-Timers by another Vietnamese veteran, Gustav Hasford. Herr recalled the next three years as one endless phone call with Kubrick. The two wrote the first drafts of the script. Gustav Hasford joined in the development of the detailed script. The script was constantly changed by Kubrick, including during filming.

The title Full Metal Jacket comes from a catalog of weapons that Kubrick came across one day. The director decided that this term (defining the so-called full-jacket bullet, i.e. in a special steel casing, increasing, among others, its effectiveness in piercing the target) sounds beautiful, menacing and poetic. The raw form of the book was adapted into a surgically precise and sterile like an operating room, war movie, the likes of which the cinema has never seen before. War, because Kubrick considered his earlier works to be deeply anti-war. Here, however, using pages from the recent history of the United States, he built a parable about methodically stripping soldiers of their humanity, analyzing war as a kind of psychological phenomenon.

From the fact that the film is divided into two distinct parts, it is clear what Kubrick was most interested in. He treated the story and the factual concreteness resulting from the setting of part of the action in Vietnam a bit neglected, as a continuation that had to be, but which did not determine the value of the work as a whole. Kubrick planted all his genius in the first part of the film, on Parris Island, South Carolina (shot outside London, as usual), at a Marine training camp. Spanning just 28 pages in Hasford’s novel, Recruit Training is an overpowering spectacle of the destruction of their humanity with its terrifying consequence.

It begins like a good camp comedy – to the rhythm of the musically cheerful and lyrically ironic song Hello Vietnam, we see more conscripts, shaved (the whole thing is edited in Kubrick’s style perfectly to the rhythm of the song). Here, their entire past life was left on the floor in the form of evenly falling hair. Here, each of them is deprived of individual features and henceforth will be a nameless part of an efficient war machine. Suddenly, one of the most famous and iconic characters Kubrick has ever seen appears on the screen. This is marine instructor Sergeant Hartman.

It is not difficult to resist the impression that Kubrick treated him with special attention, which, among other things, was lost in the second half of the film, deprived of Hartman’s presence. Endless drills, wild screams of a sergeant spewing the most sophisticated insults (once again, Kubrick has reduced a man to a screaming beast) among the unified recruits, the repetition of meaningless barracks chants, the extremely sparsely dosed human reflexes of the soldiers, even the celebration of Christmas with the song Happy Birthday Jesus Dear – it all attacks the viewer from the first minute. The language of orders is the language of Kubrick, who seems to feel at home in this absurdly ordered world.

The first calmly given words of dialogue are not heard until the 18th minute, during the Joker’s conversation with Pyle. But after the first shock, Kubrick’s brutal method turns into a truly fascinating spectacle, gaining strength with subsequent humiliations of Private Pyle. Focusing on the physically and mentally sluggish Pyle, the director made a very characteristic, methodical analysis of the façade, called humanity, being smashed to dust in the face of an extreme situation. Again, an apparent paradox emerged.

At first, Pyle seems completely unfit, not so much for the army as for normal life. In the course of murderous training, supplemented by painful harassment from his colleagues, the fat private undergoes an incredible metamorphosis, becoming the incarnation of the perfect soldier. So all is well and point for Hartman? Well, no. Pyle begins to behave like an overloaded computer from 2001: A Space Odyssey or ghost-dominated Jack Torrance. The viewer goes crazy with him, initially sympathetic, then cheering for Hartman’s effectiveness against Pyle, only to admit the private’s lost humanity at the end of the famous toilet scene. The training was successful, the man died. Again.

With the action shifting to war-torn Vietnam, a completely different movie suddenly begins. Instead of camp psychodrama, Kubrick serves up a piece of the strangest Vietnam film imaginable. Joker and Rafterman’s journey as war correspondents from the Marine base in Da Nang to the city of Hue is replete with fantastically shot and staged action sequences, adjacent to unexpectedly light drama and comedy scenes. Bearing in mind the two greatest films about those events: Apocalypse Now and Platoon, the twisted methodology of the director is clearly visible, trying to play his own chess game in the same scenery. Coppola struck the viewer with an almost narcotic vision of a journey to the heart of darkness, Stone was documentably precise, while Kubrick’s view of Vietnam appears as a land drawn from a dry imagination, populated with figures typical of the director.

Kubrick does not digress too much on the moral aspects, readable to the American viewer, although the barracks part was full of patriotic platitudes and fervent paeans in honor of Uncle Sam. What is striking in the second half of the film is the blending of Kubrick’s murderous irony with the lack of his trademark narrative discipline. Several dozen minutes of the film is a bizarre patchwork, made of battle scenes, jokes about masturbation over the bodies of fallen soldiers, a verbal duel between the Joker and a soldier called Animal Mother with ammunition belts, negotiations between soldiers and the price list for the services of a slant-eyed prostitute, and a completely surreal sequence with the film crew (here Kubrick was very proud of the use of the crazy song Surfin’ Bird). Maybe the director wanted to deliberately outline the chaos created in the characters’ heads, or maybe he simply lacked a character worthy of Hartman in Vietnam, who would synthesize this mess into a plot-precise spectacle from the first part.

Fortunately, the last 30 minutes is a spectacle involving purely physical dynamics of the highest quality. The fight with the sniper hidden among the ruins brings back the feeling of communing with a high-quality film work, although Kubrick has not completely rid himself of the exceptional emotional coldness he gave to the characters and the whole strange, quasi-real world. Both Parris Island and Vietnam are just conventional scenery, and Kubrick’s method, in a collision with not so distant and well-known history, resulted in a bizarre hybrid. The experience of the two co-writers was definitely covered up by the obsessions of Kubrick, who could not boast of war experiences and made it clear that this was not his vision of Vietnam, but the next chapter of an anthology about the human condition.

The Joker’s epic is somewhat reminiscent of Redmond Barry’s war story, but the comparison of the two characters is definitely in favor of the hero from Thackeray’s novel. Despite his cleverness, sense of humor and ability to reflect, Joker is just a comfortable conformist whose moral degradation somehow does not arouse any special emotions or surprise. Because of this, even the theme of human duality (the peace symbol on his uniform and the inscription “Born to kill” on his helmet) that he flaunts seems to be poorly motivated. The only characters that evoke strong emotions are Hartman and Pyle. R. Lee Ermey was originally intended to be only a military adviser and consultant. According to the legend, Ermey sent Kubrick a videotape, on which he yelled the most elaborate insults directly at the camera for several minutes, not once repeating himself, which after being put on paper made as many as 240 priceless pages. Although he had already played small roles as soldiers in three films (including Apocalypse Now), only in Full Metal Jacket R. Lee Ermey took over the screen completely, because he actually played himself (Ermey was a Marine Corps instructor on Parris Island).

Ermey’s first days on the set, still as a consultant, were interesting. The sergeant categorically stated that the actors playing the Marines sucked. When the director denied it, Ermey pulled off his signature stunt by yelling at Kubrick to lift his respectable ass when the commander was talking. Startled, Kubrick stood up, and Ermey already had the role of Hartman in his pocket.

Later, much to Kubrick’s delight, Ermey personally redid over 50% of all of Hartman’s lines from the script, as well as oversaw the construction of all of the Parris Island sets. The only thing he didn’t do during the shoot was… blink. Stanley Kubrick was very pleased with his military actor, as evidenced by the few doubles of scenes with his participation. R. Lee Ermey was involved in a car accident while filming, which broke almost all of his left ribs. Shooting with his participation was canceled for four months. Ermey did not want to prolong his recovery any longer and returned to the set. The post-accident scenes are easy to identify because the actor kept his left arm bent behind his back. In order to extract maximum credible obedience from the actors, Ermey only appeared on set during filming and did not interact with the rest of the cast. The actor jokingly referred to his creation in one of the episodes of Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners, where as a ghost he performed more or less the same as for Kubrick.

Almost all of the actors were selected by Kubrick based on video castings in the United States. Only the casting of a few of the main characters was done live by him. The first candidate for the role of the Joker was Anthony Michael Hall, who quickly said goodbye to the director, unable to stand his specific style of work. He was replaced by Matthew Modine. Selected for the role of Pyle, 26-year-old Vincent D’Onofrio put on 26 kg for the film, which broke a kind of dedication record for a role held by Robert De Niro in Raging Bull. Kubrick himself exceptionally appeared on the other side of the camera, but only in the form of the voice of Murphy, the commander giving orders to Cowboy over the phone. Do not try to look for the discography of Abigail Mead, the author of the music for Full Metal Jacket. The reason is simple. Hidden behind this pseudonym was Vivian Kubrick, the director’s daughter, who traditionally also played an acting cameo. She can be seen with a film camera in the scene with the mass grave of the Vietnamese.

Full Metal Jacket was supposed to be photographed by John Alcott again, but he chose to work on the thriller No Way Out with Kevin Costner. He was replaced by his former assistant Douglas Milsome, debuting with Kubrick as an independent DP. And for John Alcott, working on a Roger Donaldson film was also his last. The master of camera and light died of a heart attack on July 28, 1986.

Despite this change, the camera work in Full Metal Jacket is unmistakably characterized by Kubrick’s style and Alcott’s elegance. Long steadicam rides, mathematically composed static shots, slow zooms with soldiers’ faces, and when necessary, a switch to shaky handheld shots (as in several scenes with Pyle during practice) – all underlined by the excellent editing of newcomer Martin Hunter, is the most distinctive visual feature of Kubrick’s films. In the Hue approach sequence, Douglas Milsome innovatively used an accelerated shutter, which was later masterfully used by Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski in Saving Private Ryan.

Kubrick made no mistakes. First of all, it’s about the first scene with the recruits and Hartman. During the long shot of the sergeant’s opening speech, Pyle is standing by the last bunk in the row. But after Joker’s famous words “Is that you, John Wayne? Is this me?”, there is an odd switch of places for both Joker and Pyle.

Full Metal Jacket is an extremely interesting example of scenographic illusion. Making the British Bassingbourn Rifle & Pistol Club shooting range an imitation of the barracks on Parris Island in South Carolina, USA, is relatively easy to imagine. The real surprise was that also the Vietnamese locations were built near London. Palms were imported from Spain, and thousands of plastic imitation plants and shrubs from Hong Kong. Based on wartime photographs of the Vietnamese city of Hue, Kubrick found something very similar in London’s Idle of Dogs and in the East End, with 1930s demolition buildings once the Beckton Gasworks.

After minor decorating tweaks, Kubrick seized the unique opportunity to play the final shootout amid authentic concrete, joyously destroyed by pyrotechnics. The two-month leveling of the ashes to the ground was carried out under the supervision of a set designer and cameraman, who thus received a ready set for filming. A set whose construction and deliberate destruction would cost a lot of time and money if it was erected using methods typical for film production. In Cowboy’s death scene, one stands among the destroyed buildings as a vivid resemblance to the Black Monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Although it looked like a wink at the viewer, Stanley Kubrick denied rumors of the intentional placement of this burning shape among the decorations, blaming it on pure chance. Only the helicopter shot at civilians, plus some aerial shots, were shot in Asia by a second camera crew. The real Parris Island barracks is only seen in two archival oath shots.

Several scenes were dropped from the film. Kubrick did not shoot the scripted scene of Pyle being drowned by Hartman in a barrel of urine; he also shied away from making the episode with the soldier who slit his wrists, whom Hartman tells to clean up the blood first, rather than sending him directly to the doctor. The director did not want to exaggerately demonize Hartman, focusing rather on his understandable for the viewer, having an exclusive training background, ruthlessness. Among those filmed but rejected for editing were scenes of soldier football involving a human skull and the Joker’s quickie with a Vietnamese whore. As a complete coincidence from Hasford’s book, Kubrick noted the similarity between the finals of Full Metal Jacket and Paths of Glory – both films end with a woman surrounded by enemy soldiers.

Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford received an Oscar nomination for their adapted screenplay Full Metal Jacket. Both writers unanimously emphasized Kubrick’s genius, although they admitted that the film differed intellectually from their own experiences on paper. It should be added that in 1990 Gustav Hasford published the novel The Phantom Blooper in which he added a further, very surprising story of the Joker, who, fighting at Khe Sanh, is captured by the Vietcong and eventually joins the Vietnamese army. The marines “rescue” him. After returning to the US, Joker joins the opponents of the war, he also visits Cowboy’s parents. But unable to cope with the past, he returns to Vietnam as a journalist.

A year of shooting, a budget of $17 million, a great staging and a number of completely unique scenes in the history of cinema, unfortunately, in a broader perspective, did not translate into an exceptional film about the Vietnam War. It took seven years to make Full Metal Jacket. Way too long. Stanley Kubrick was overtaken by Oliver Stone with the Oscar-winning Platoon, Francis Ford Coppola and his Gardens of Stone were also two months faster (not to mention the cheesy Missing in Action movies with the divine Chuck Norris!). I wonder how Kubrick’s career would have developed if Umberto Eco had allowed him to film Foucault’s Pendulum, which the director was very eager to make in the first half of the 1980s. Anyway, the great visionary fell in the clash with the latest history, which did not prevent him from further exploring the subject of war…

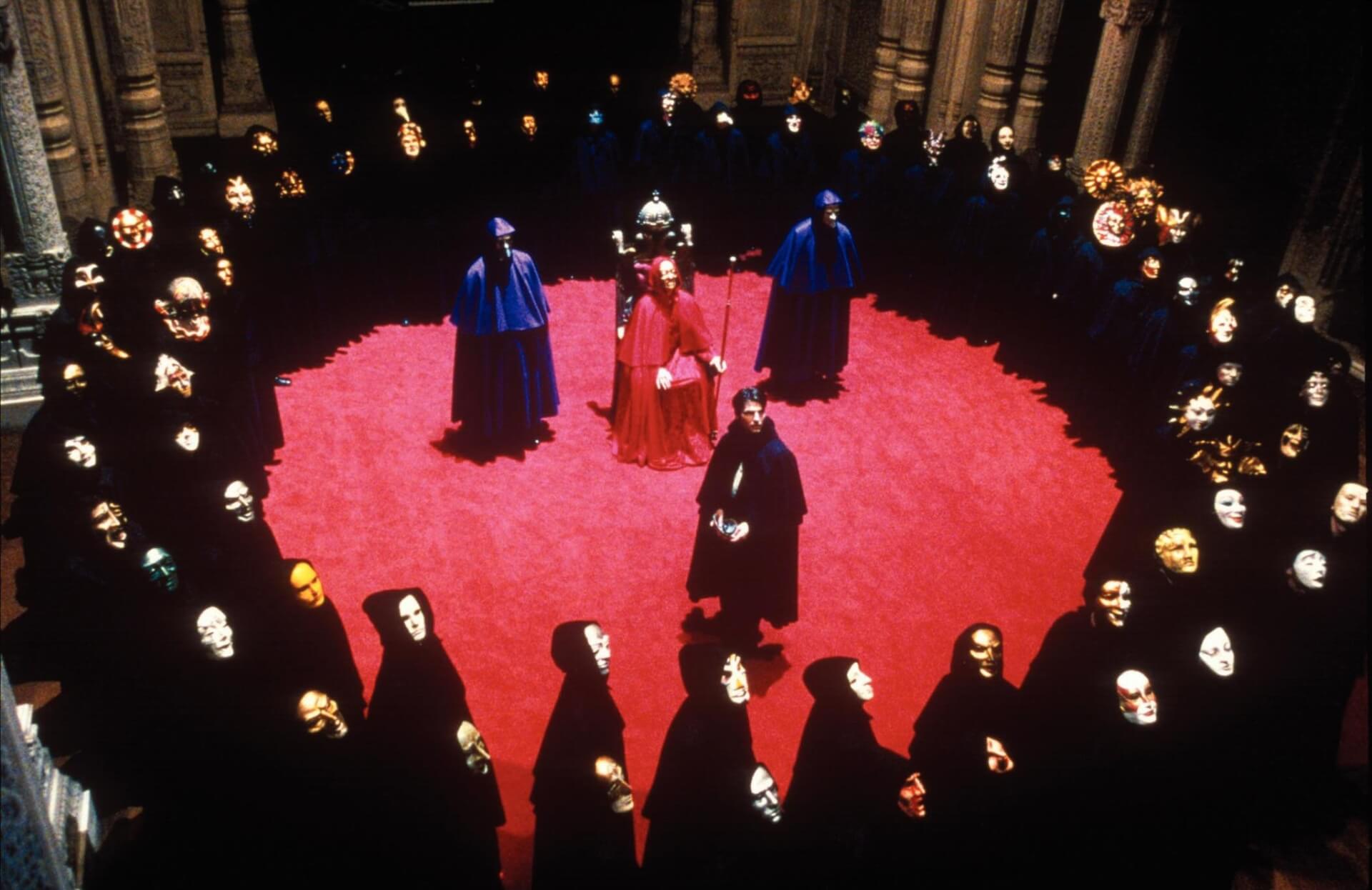

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

New York doctor Bill Harford learns of perverse erotic fantasies involving a strange man by his wife, Alice. Looking for an outlet for his obsessive frustration, he meets a prostitute. At the urging of his friend, he gets to a secret masquerade ball, which is in fact a gigantic sex orgy. Exposed and humiliated, Bill sees his ballroom mask next to his sleeping wife one night…

Throughout the 1980s, Stanley Kubrick considered the idea of making a film based on Brian W. Aldiss’ short story Supertoys last all summer long. It was a story set in a hostile, overcrowded future where a child permit can only be won in a government lottery. The heroine of the story, Monica, who dreams of a child, while waiting for her chance, is raising a robotic child named David. At that time, Kubrick was in constant contact with Steven Spielberg, rightly considering this project as close to the creator of E.T. But the visual effects technique of the time did not allow to satisfy the director’s high expectations.

In 1991, Kubrick became interested in the story of another boy, but from a completely different place, contained in Louis Begley’s novel Wartime Lies. It was a story about 9-year-old Maciek from a Jewish family in Poland, who is hiding from the Nazis taking over the country during World War II. He hides in a rather unexpected way, pretending to be a non-Jew, like the hero of Agnieszka Holland’s Europa Europa. The axis of the plot was supposed to be the nightmare of a young man who, avoiding the Holocaust, experiences no less torment related to watching the death of his loved ones. Preparations for the script, entitled Aryan Papers, were in full swing. Joseph Mazello (Jurassic Park) was to play the boy, and Julia Roberts or Uma Thurman were considered for the role of his mother. But again the story repeated itself, like 20 years earlier with Napoleon. Spielberg made Schindler’s List, which caused Kubrick to abandon Aryan Papers.

At this point, Steven Spielberg appeared again and his Jurassic Park (1993) convinced Kubrick that digital technology would finally be able to realize his dream project A.I., based on Aldiss’ short story. In the mid-1990s, Kubrick realized that no studio would finance this project for a director who had made literally nothing since 1987. Then Kubrick proposed to Spielberg to direct A.I., contenting himself with the role of producer.

Spielberg honorably declined, explaining that it was Stanley’s exclusive project. So Kubrick made a deal with Warner Bros. Before the studio spends a fortune on the uncertain project of a director who has been silent for years, Kubrick will make another, more modest film earlier, which will prove that the long break has not deprived him of the ability to attract viewers to cinemas. To this end, he dug from memory the novella Traumnovelle, written in 1926 by Arthur Schnitzler, which he read in the 1970s.

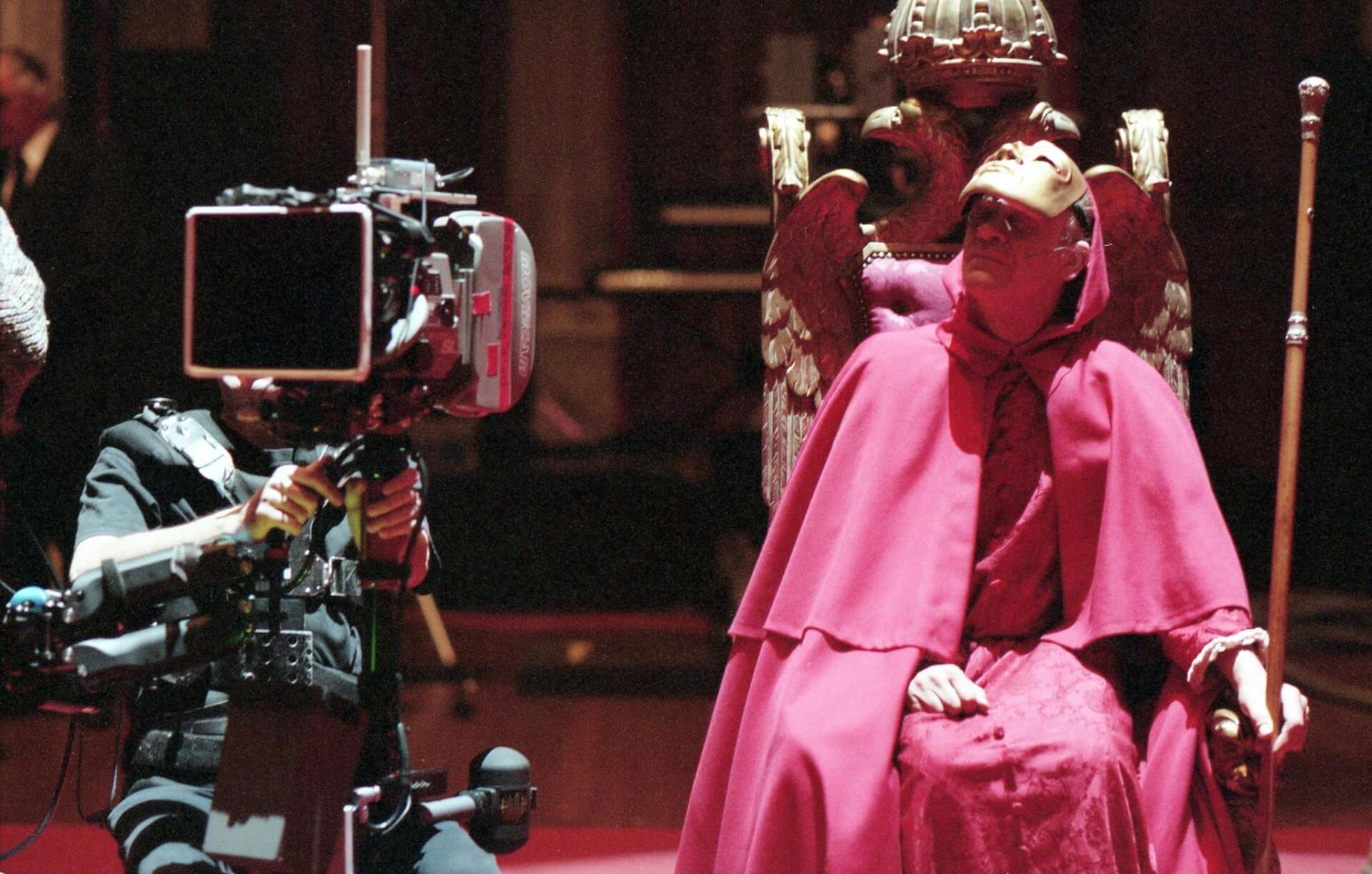

The tabloids were buzzing with rumors, trade magazines also wondered what secrets were hidden behind the tightly closed halls of Pinewood Studios. The enigmatic information about the “story of sex, betrayal and fidelity” made by the cinema legend, who has been silent for many years, was ignited by the role of the model Hollywood married couple Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman (in the 1980s the director wanted to cast Steve Martin in the lead role).

Filming began on November 4, 1996. Cruise and Kidman signed open-ended contracts, while the rest of the key cast took an unexpected turn. Harvey Keitel, who was cast as Victor Ziegler, couldn’t stand working with the retake-obsessed director and left the set. His place was taken by the famous director Sydney Pollack, often also acting on the other side of the camera (Kubrick also considered entrusting this role to… Woody Allen). Jennifer Jason Leigh managed to shoot all the scenes as Marion Nathanson, the daughter of Dr. Harford’s deceased patient, professing her love for the doctor in front of her father’s body. But Kubrick decided that Jennifer had not performed as she should and called her back to the set. The actress was busy on the set of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, so her role was entrusted to the Swedish actress Marie Richardson. Filming was completed in June 1998. It took almost a year to assemble this ultra-precise dramatic puzzle. Was it worth the wait?

The only right answer is “Kubrick is always worth a wait”! The director himself, after finishing the film, managed to confess: “this is my best film”. Is it really? On the one hand, the $65 million Eyes Wide Shut is an extraordinary work, woven from scenes and moments that no one else would have shot. The slow pace of the 2.5-hour film does not put you to sleep and does not bore you, on the contrary, it creates an invisible, hypnotic envelope around the viewer, from which it is impossible to break free. After the screening, the viewer even wants a few more hours spent in the intricately intertwined web of dark passions of the main characters. The actors did a fantastic job and Nicole Kidman played the part of her life here.

Visually, Eyes Wide Shut is – how else – the Kubrick we have known and admired for 40 years. The already mentioned long rides filmed with Steadicam, precisely, almost mathematically composed static shots, the pace of editing synchronized to the music, unhurried, dignified narration – elements of Kubrick’s style, despite the years of break and the changing rules of film storytelling, have survived intact. Eyes Wide Shut resembles a journey to the past, when the most important thing was the elegance of the staging, the desire to maintain the expressiveness of the visual style, closely corresponding to the meanders of the plot. Kubrick and his cinematographer Larry Smith approached the film’s color concept with reverence. Each colorful patch in the frame is closely related to the mental state of the characters.

An echo of John Alcott’s experiences on the set of Barry Lyndon is the party scene at the Zieglers’, illuminated only by the living room lamps visible in the frame. But on the other hand, there is also a note of anxiety with a deja vu effect. Especially for Stanley Kubrick scholars, the film is somewhat predictable, like a game of marked cards. At every turn, the director emphasized how HIS film was, how his unique way of telling stories, cultivated for decades, still MUST work. And it actually works flawlessly, it’s impossible to imagine Kubrick’s film otherwise, but despite this, his latest work is a bit like eating his own tail, cutting coupons from the laboriously elaborated script and technical concepts that made his previous masterpieces great. It’s all been done before, and in a more exhilarating style.

Methodical vivisection, how demons are born under the mask of normality, bourgeoisie, marriage, was not as perfidiously thrilling as Jack Torrance’s study of madness. Leaving aside the comparison that what for others is the ceiling, for Kubrick is the floor, Eyes Wide Shut was not the masterpiece for which viewers had been waiting for so many years. The bit of madness that Kubrick had when he was younger was missing.

The film was traditionally made in Great Britain, and the wide street plans of New York are the work of a second camera unit. Bill Harford’s name is an abbreviation of… Harrison Ford, because Kubrick saw the character played by Tom Cruise as a typical American (as opposed to co-writer Frederic Raphael, who, according to the literary prototype, wanted the main character to be Jewish, named Scheuer). The director’s adoptive daughter, Katharina, and her son played Dr. Harford’s patients. The traumatic music that illustrates the beginning of the orgy includes a church song played backwards in Romanian.

Harford’s pivotal conversation with Ziegler at the pool table took three weeks to shoot. The Harford apartment was built after the Kubricks’ New York apartment from the 1960s. When choosing the right tape, Kubrick and Larry Smith chose one of Kodak’s negatives, which the producer himself did not take into account when filling the order. The orgy sequence was censored in American theaters by digitally adding people and props to obscure the most promiscuous parts of the shots.

Kubrick included a large number of self-quotes in the film. The inscription on the wall of a building in Soho contains the word “bowman”. That’s the name of the astronaut in 2001: A Space Odyssey. From the same film comes the surname Kaminsky. That’s the name of Dr. Harford’s patient. Harford’s mask, worn during the orgy, has the features of Ryan O’Neal, who played the title character in Barry Lyndon. In one of the scenes on the screen you can see a TV set showing the film Blume in Love, dir. Paul Mazursky, who starred in Kubrick’s debut Fear and Desire. The morgue where Bill finds Mandy is in the hospital’s C Wing, room 114 (C room 114, CRM-114). That was the codename for the cipher machine on board the bomber in Dr. Strangelove, that was on one of the capsules of the Discovery ship in 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the same was on the vial of medicine given to Alex in A Clockwork Orange. A newspaper article about the deceased prostitute Mandy mentions a man named Leon Vitali. This is the name of Kubrick’s longtime assistant and friend, who played the grown-up Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon and the leader of the orgy in Eyes Wide Shut. In the scene where Bill Harford sees his mask next to Alice sleeping, there is a brief glimpse of a stack of Stanley Kubrick videotapes lying on a coffee table.

Stanley Kubrick died of a heart attack on March 7, 1999 at his Childwickbury Manor estate in Hertfordshire, just four days after finishing editing Eyes Wide Shut. He was 71 years old. He left behind amazing films. He was able to lead the viewer to spiritual ecstasy, he could lead the critics astray, and he could drive a co-worker into a nervous breakdown. He is cordial towards his relatives, merciless towards his co-workers, often towards people who were both for him. Like no one else, he focused on every detail of his Work, extracting insights that were astonishingly accurate from the most seemingly trivial elements of the script puzzles.

Controlling every aspect of the production, he showed what a truly uncompromising original message is all about, independent of the skills and opinion of the people he surrounds himself with. With the help of the camera, he created worlds drawn from the subconscious, swollen with the most pressing moral problems. He was able to answer questions that others were afraid to ask. An artist whose genius changed the face of world cinematography forever.

He died before witnessing the century that 2001: A Space Odyssey made famous. Stanley wanted us to see his films exactly as he did. He emboldened us with the courage of his convictions, and then he carried us into his world, his vision. And you will not find another like it in the entire history of cinema. It is a vision of hope, miracles, beauty and mystery. Once a gift, it is now a legacy that will inspire and nourish us as long as we are brave with his boldness. And I hope it will last long after all the thanks and goodbyes have sounded – Steven Spielberg at the Oscars, March 21, 1999.