WAXWORK. Visually surprising mix of horror and comedy

…the semblance of humanity, but also the terrifying possibility that at some point, these motionless exhibits will come to life. More often than not, the shining wax conceals not monsters, but the victims of a madman’s twisted imagination. This was the case in both versions of Mystery of the Wax Museum, conceived by Charles Belden (the first film from 1933 directed by the future creator of Casablanca, Michael Curtiz, and the next one, directed by André De Toth, starring Vincent Price, was made 20 years later), and in House of Wax Bodies, an impressive but silly slasher by Jaume Collet-Serra. Regardless of the role they play in the story, the glistening figures are unsettling by their mere presence, displaying the human body in all its perfection and yet lifelessness. If there’s something to be afraid of, it’s this unnaturalness.

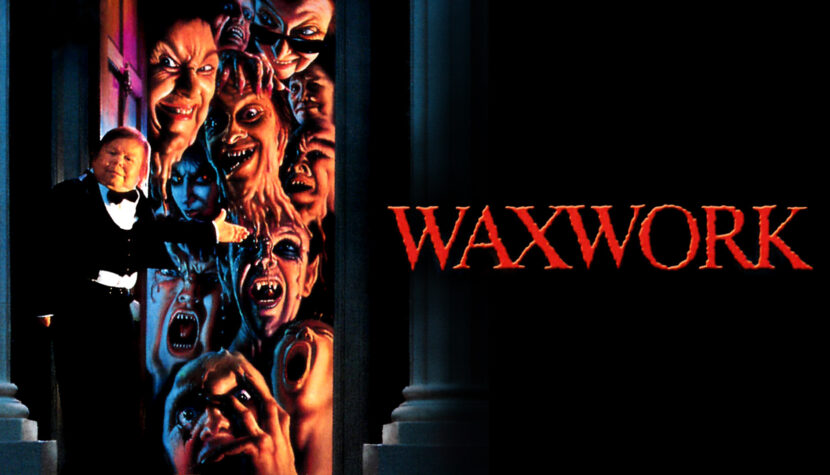

In Anthony Hickox’s Waxwork the titular sculptures feature famous literary monsters (Dracula, The Phantom of the Opera), cinematic ones (zombies straight from Night of the Living Dead, the classic mummy), and real historical figures (Marquis de Sade, Jack the Ripper). However, not all of them are a pleasant sight up close. When a group of pompous students is invited to a nighttime wax figure show by a flamboyantly dressed man who immediately signals his own insanity (exaggerated by David Warner), they cannot foresee the realism they are about to encounter. After crossing the barrier separating the exhibits from the audience, the youngsters find themselves directly inside the stories of the wax figures. The British director has a lot of fun staging individual one-act plays with the specific characteristics of each story, giving each one its own pace, atmosphere, and tone.

These are the best moments of the film, which thematically draws the most from another Waxworks, specifically the expressionist work directed by Paul Leni in 1924. In that film, the protagonist also immerses himself (thanks to his own imagination) into a plot in which the wax figure takes the lead, consisting of several episodes differing in genre. Hickox, on the other hand, strikes the perfect balance between horror largely based on gore aesthetics and comedy about contemporary bourgeois individuals confronting their worst nightmares, which were somewhat unwelcome guests in at least one instance. After all, isn’t an encounter with Count Dracula in his castle what China (played by the cool Michelle Johnson) dreamed of, expressing her desire to meet a distinguished foreigner?

The character Sarah, played by the ethereal Deborah Foreman, chooses to submit to a flogging by the Marquis de Sade himself instead of picking the handsome, wealthy, and lovelorn Mark (Zach Galligan, known for Gremlins). When Sarah rejects her suitor’s advances, explaining that she is waiting for someone entirely different, we have no idea what her ideal might be. Hickox, who not only directed the film but also wrote it, strongly suggests that entering the fantastic world of wax figures risks becoming entwined with the role of the victim prepared for the main characters. However, he is inconsistent in this regard. While women succumb to their handsome captors, conforming to the story, the men remain aware of their own identities throughout, trying to escape the monsters waiting for them. Therefore, the episodes with China and Sarah stand out with a more serious tone and strong erotic undertones, while Tony’s encounter with a werewolf or the pursuit of the living dead after Mark, although not devoid of tension, clearly lean towards humor.

Waxwork does not even attempt to hide its parodic tone, which is evident not only in the literal entrance of the characters into the realm of horror. Except for the quiet Sarah, the youthful characters are portrayed in their natural environment as pampered and spoiled poseurs, glaring with their inauthenticity, much like wax figures. However, this comparison is more a result of the narrative construction than what we see on screen. The pastel colors of wealthy American suburbs and conventional plot solutions, typical of 1980s cinema, do not align with the hidden thought that ties the whole story together and gives it unexpected value, as if Hickox, while moving towards overt parody, failed to recognize the underlying theme that connects the entire story.

How much better would Waxwork have been if its creator had set the action in his native country? England seems like an obvious choice for a story in which Mark’s noble birth is emphasized so strongly, and the style of individual episodes is more reminiscent of British Hammer productions rather than earlier American films from Universal Studios, which also specialized in horror during that time. Furthermore, Anthony is the son of Douglas Hickox, also a director, primarily known for Theatre of Blood, in which Vincent Price plays a failed actor who murders his critics one by one. In that film, too, the criminal used classical themes, drawing inspiration from Shakespeare’s works, and the victims found themselves in the middle of a spectacle created especially for them. Unlike his son, Hickox senior doesn’t succumb to pretense – horror resonates with him until the very end, although there is still a substantial dose of dark humor.

Anthony Hickox’s Waxwork doesn’t take advantage of the opportunities to be more than a B-movie horror comedy, based on a promising concept and interesting observations, settling for macabre humor. All ambitions are stifled by the director’s flashy and technically skilled but not particularly reflective approach. Hickox’s subsequent filmography only confirms this – Sundown: The Vampire in Retreat, Hellraiser III, Warlock: The Armageddon, and Solar Eclipse are works that are often visually surprising and creatively executed, but they squander a good starting point for showcasing technical proficiency, ultimately becoming tiresome. I appreciate Hickox’s debut for its uninhibited play with genre classics, but after a recent viewing, it’s hard not to regard the film as a minor disappointment. The director focused all his attention on wax, which, after 30 years since its release, has lost some of its luster but is still far from melted away.