THREE DAYS OF THE CONDOR: A Paranoid Thriller Masterpiece

It’s not even about aging like fine wine, becoming more enjoyable with time. It’s simply that the relentless passing of years not only fails to expose their flaws but actually adds meaning to their content, making them seem even better than on the day of their release. A perfect example of such a production is a work by Sydney Pollack, which this year celebrates its 50th anniversary. While it was already an exceptionally good, even brilliant film in its genre at the time of its premiere—produced during the most outstanding period of American cinema—the days marked on the calendar quickly revealed that Three Days of the Condor had smuggled far more under the guise of cheap entertainment than anyone could have initially suspected. Today, it’s not only a genre classic but also a precursor to an entire wave of similar films—a movie that, in a way, was ahead of its time.

The adaptation of James Grady’s novel was an obvious aftermath of the Watergate scandal, which gave rise to a sea of other cinematic hits criticizing various government conspiracies and simultaneously shattering the myth of the American Dream—the illusion of faith in the system and the institutions governing it (and not even necessarily the politicians per se). The protagonists thus became individuals who had lost trust in their own country—tired, tormented by constant suspicions, often hunted and placed in hopeless situations, uncertain about tomorrow, and sometimes even devoid of a future altogether. Characters with a heroic bent, still upright and innocent in their own way—much like the suddenly matured Joseph Turner in the flawless interpretation of Hollywood’s golden boy, Robert Redford—but far removed from the typical, flawless heroes of “stars and stripes” narratives. These are ordinary people, lost in new circumstances, who simply want to survive and, incidentally, hope to do something good in the name of the ideals in which they were raised.

Working for the CIA in one of its seemingly insignificant branches, a frivolous, undisciplined young man engrossed in Dick Tracy comics—whose primary task is to analyze content and search for hidden meanings in books and press from around the world—is thrown into action after his colleagues are unexpectedly murdered in his absence. He doesn’t want to share their fate, though he has no idea why the crime occurred. And this happens almost in the heart of American values—New York City, the city-symbol, home to the Statue of Liberty and the (then-standing) twin towers of the World Trade Center—on a bright day, under the noses of unsuspecting citizens.

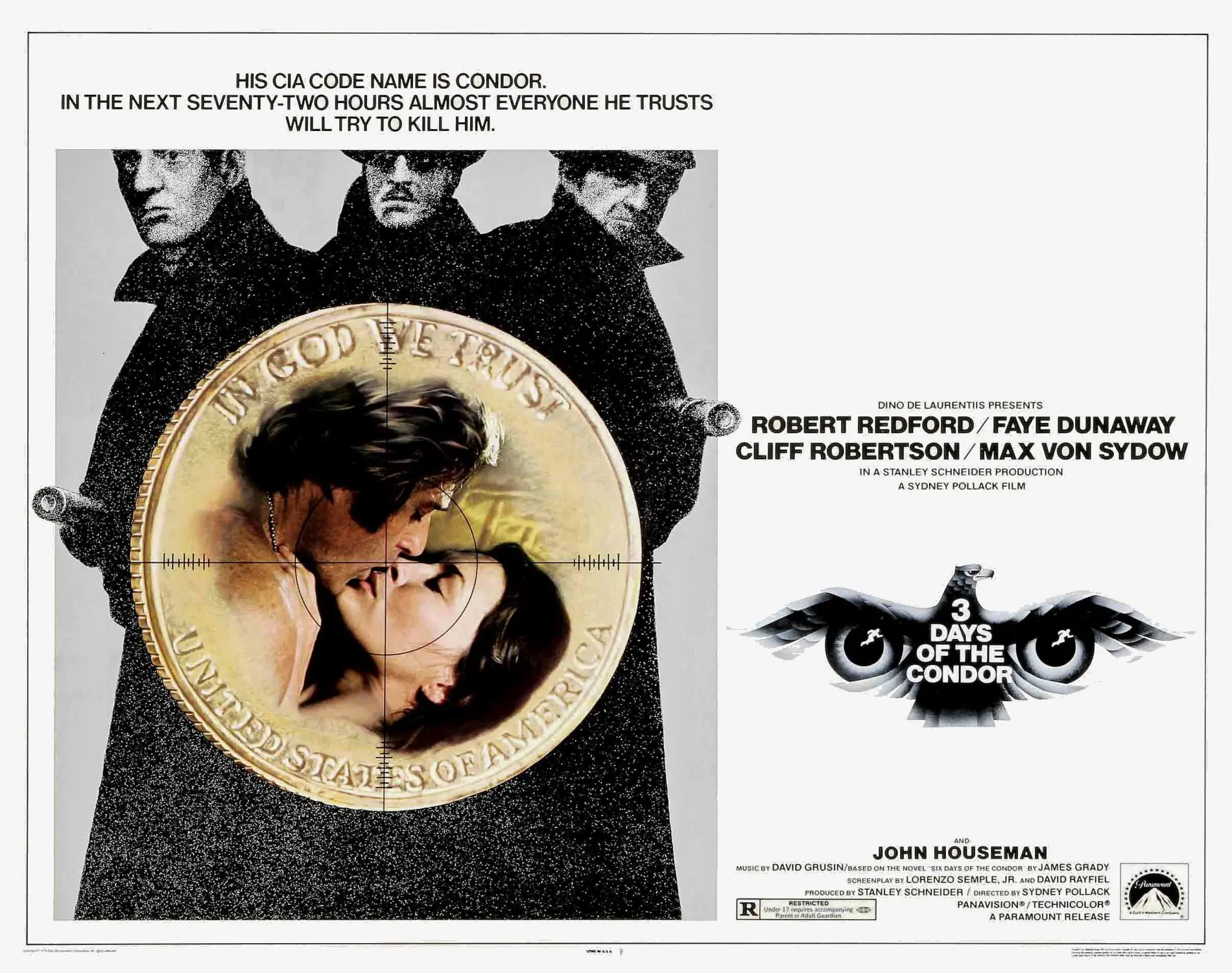

Acting on impulse and sheer chance, Turner kidnaps an innocent woman off the street (the always delicately charming Faye Dunaway, nominated for a Golden Globe for her performance), with whom he then hides. Using his skills, knowledge, wit, and experience, he tries to piece together the events of the last few hours, attempting to make sense of them. And being no fool, he manages quite well for a bookworm. Meanwhile, the agency that used to pay him—represented by the ever-reliable Cliff Robertson as the calculating Higgins—targets Turner, seeing him as a potential threat to national interests, perhaps even a spy. They send professionals to silence him, including the excellent Max von Sydow in a role originally intended for Lino Ventura, portraying a cultured assassin with his own set of principles who deeply understands Turner and his predicament. However, they underestimate the unpredictability and determination of their former subordinate…

It’s intriguing—though hardly surprising—how much the film differs from its literary source.

Pollack, together with Redford and screenwriters Lorenzo Semple Jr. (Papillon and later Flash Gordon and Sheena: Queen of the Jungle) and David Rayfiel (Jeremiah Johnson, The Firm), gave the world one of the finest adaptations of the written word, capable of competing with other masterpieces of the 1970s like The Godfather or Jaws (with which it lost its sole Oscar nomination for editing). Within a year of its release, they transformed Grady’s tacky, over-the-top, Bond-esque literature into a fully-fledged, intimate, and intelligent spy story. Six days turned into just seventy-two hours, where exaggerated, flashy action sequences (including parachuting into Washington D.C.) were replaced by suspense and character development. The drug-laden, implausible intrigue and equally unrealistic romance were replaced by a conflict over oil and a brief, melancholic affair—born out of loneliness and depicted through stark, black-and-white imagery of deserted, desolate spaces—a fleeting connection with no chance of a lasting relationship, which neither of the lost lovers actively seeks, even if they secretly dream of it.

The lack of a happy ending, as well as clear answers to the questions raised during the screening, perfectly fits the cold, harsh, disillusioned style of that decade, which mercilessly dismantled the American myth. Owen Roizman’s calm, almost static but claustrophobic and grayscale cinematography underscores the hopeless atmosphere. Similarly, Dave Grusin’s jazz-tinged, seemingly upbeat but melancholic score (Grammy-nominated) adds to the dense mood. The somber season of the action, though a bit of a cheat—the filmmakers faked winter during autumn, removing leaves from trees on set, an unthinkable act today—aligns well with the project’s tone, aptly summarized by Redford in one scene as “transitional.”

Indeed, this was a “transitional” period for the U.S.—shortly after the film’s release, more governmental revelations and scandals surfaced. Oil, already a key plot point, became the cause of real-world conflicts in subsequent decades—still a pressing issue today, far more serious than it was when it merely added authenticity and drama to the film. As always, reality surpassed the film in every aspect. Beyond technological advancements that would now easily eliminate Joseph Turners without leaving the office, there’s the matter of media and press control—a subtle theme in Pollack’s film, hinted at in its final scenes. Redford would revisit this topic multiple times, whether in the equally absorbing All the President’s Men or his Condor-inspired appearance in a Captain America installment.

This production is thus a paradoxical example of a motion picture that has both aged and matured.

On one hand, it commands respect with its unhurried pace, devoid of spectacular scenes (the entire film features just one fistfight and a modest shootout), yet gripping in its tension and remarkably realistic, thorough approach to the subject. On the other hand, the world outside has long since ridiculed this vision, turning it into a tale that, while perhaps not naive, feels exceptionally tame and—even though the term isn’t quite right—safe in its message. It’s a bird with clearly clipped wings but an equally strong will to live. It can still take flight with ease and captivate with its majestic soar.

Nevertheless, there was a time when Three Days of the Condor disappeared from cinephiles’ radar, resurfacing in the late 20th century amidst scandal (the infamous 1997 lawsuit where the director sued a television station for showing the film in improper aspect ratios, undermining its intended expression). Despite significant commercial success—over sixty million dollars in U.S. box office earnings alone—and critical acclaim, it remained unavailable on home media in some countries for years.

A sequel, which seemed likely given the film’s open ending and numerous political upheavals ripe for commentary from someone like Pollack, was never made. Pollack, a director who often successfully appeared in front of the camera as well, lent his voice to the film twice here. And Grady attempted to support filmmakers by releasing a novel titled Shadow of the Condor in 1978—still unadapted for any screen. Whether it or the more recent sequels penned by the author—Last Days of the Condor and Next Day of the Condor (yes, really)—would be good material for bringing Condor into 21st-century cinema is a question worth asking. Rumors of a television remake persist, one that could offer a compelling voice in a post-Snowden reality and expand on the character of the likable Section 9, Division 17 guy, who over the years has likely grown more jaded, exploring his motives, struggles, and survival tactics. The question remains whether it’s too late for such a hero.

Would the adventure lose its unique magic in today’s high-tech, sophisticated serial storytelling? Would Pollack’s unmistakable atmosphere, which, although he wasn’t the producers’ first choice (Peter Yates was originally slated to direct with Warren Beatty in the lead), still managed to imbue this bird conspiracy with warmth—not just through subtle love scenes offering a moment of respite—fade away? Pollack gave the story a distinctly humanistic touch, winning over audiences while deeply engaging them with the content, compelling them to think, and perhaps even act accordingly. Such cinema is always valuable. Such films I always value. And I always recommend them. Three Days of the Condor is a priceless gem that should be cherished by every viewer.