THE THIRD PART OF THE NIGHT. Oneiric Apocalypse In A Godless World

However, it is hard to think of a more fitting setting for intense horror cinema that delves into the traumatic experiences of individuals amidst the chaos of war.

This seemed to be the mindset of Andrzej Żuławski when he made his full-length debut in 1971. The Third Part of the Night is, in every aspect, an unconventional film that escapes traditional schemes. In it, the war experience is rewritten into a labyrinth of faces, bodies, and events, stretched between Kafkaesque existentialism and religious illumination. In this madness-soaked film, Żuławski also created a kind of manifesto of his expressive, madness-infused style.

In The Third Part of the Night, the novice director, educated in France and gaining experience in Poland during the 1960s as an assistant to Andrzej Wajda, tackled a personal story from the time of the German occupation of Lviv, where his father, Mirosław Żuławski, supported the family by working as a lice feeder at the famous Weigl Institute. According to the film’s creator, the team obtained permission to shoot The Third Part of the Night thanks to a memoir-based script recounting experiences at the institute, only to later film Żuławski’s extravagant story on set as an antithesis to the then-prevailing representations of war reality. Nevertheless, the precise depiction of the work of lice feeders at Weigl’s and the perspective of the protagonist exposed to the effects of the bred insects remained an integral part of the film. Żuławski’s view of the occupation was (and essentially remains) radical – instead of a humanist drama and martyrology, he proposed an aggressive, subjective vision of a man lost in a fevered state, immersed in a surreal aura of decay and mystical inclinations.

Żuławski’s film begins with a quote from the Book of Revelation (8:7-13), from which the title is also derived. This text reappears in the final scene, creating an interpretative frame for the entire story, which thus appears as a narrative of the fulfillment of a biblical prophecy from the perspective of an individual experiencing destruction. The opening sequence immediately declares the aesthetic embraced by Żuławski – a German unit attacks a manor house enveloped in autumn gloom, killing Michał’s mother, wife, and child – Michał being played by Leszek Teleszyński, a young intellectual recovering from a severe illness. The dark, brutally expressive scene is punctuated by a heretical prayer to the “merciless God” by Michał’s father. Thus, the first few minutes of The Third Part of the Night introduce the nihilistic state of the main character, besieged by the chaotic, incomprehensible, and ghastly daily life of occupied Poland.

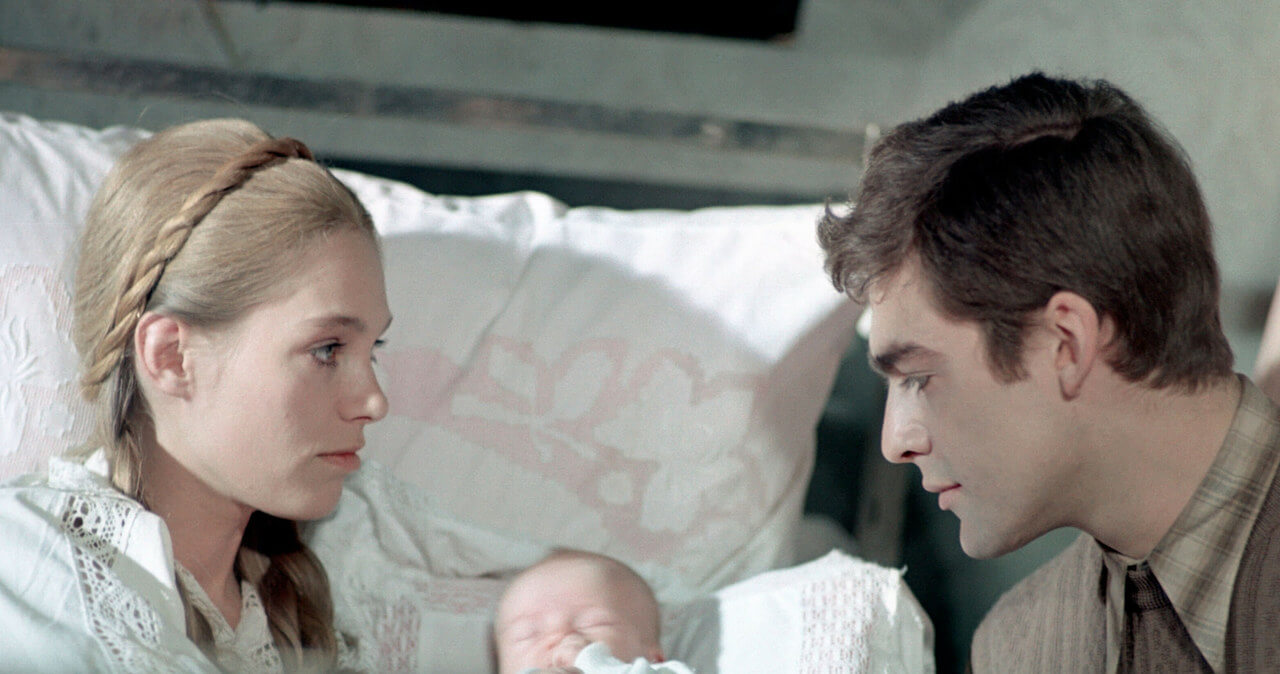

From the countryside, a shaken Michał returns to Lviv, where he is recruited into the ranks of the Home Army by an acquaintance. He soon narrowly avoids death at the hands of the Gestapo and meets the pregnant Marta, who seems to him a double of his deceased wife. Through a dramatic turn of events, he tries to take care of the stranger, whose presence evokes memories of his relationship with the late Helena, who had left her husband for him, driving the husband to the brink of madness due to the exhausting work of feeding lice. As the characters of the two women and their stories begin to intertwine and overlap, the fragmentary and inconsistent chronology loses significance in a narrative mediated by a protagonist consumed by despair and a fever induced by weakened typhus bacteria. The protagonist is ensnared by a tangle of events of uncertain reality and linearity. The viewer shares this paranoid vision, oscillating between the cruel everyday life of the occupation and a dark hallucination. By following the subjective stream of consciousness of the protagonist and not resolving his reliability or plausibility, the director immerses us in an atmosphere of decay, the irritating disintegration of the world, and shows the gradual detachment of Michał from his own identity and tangibility.

The meanings of The Third Part of the Night arise at the intersection of existential mysticism and an attempt to accurately portray the state of permanent delirium in which lice feeders were immersed. In the ravings of the terrified, war-chaos-lost Michał, the past blends with the present, religious symbols merge with underground activities, and lice bred on one’s own body become a metaphor for emotional consumption by another person and the spiritual destruction of a person by the cruelty of a world engulfed in annihilation. These orders coexist in a monstrous, surreal knot that devastates human consciousness. As one character says to Michał: one world is a reflection of another, through a mirror, which is yourself. This doubling, the ominous presence of doppelgängers, the symmetry of events, the symbolic complementarity of medicine and faith, and the fusion of the hecatomb of World War II with individual tragedy create an oneiric vision of an apocalypse in a godless world, a reality and consciousness disintegrating progressively.

For Żuławski, the fall of a mind sunk in delirium is equivalent to the end of culture. Michał is surrounded by prophets of this decay – a father burning musical notes, a Jew hiding his face under a mask, a blind commander of a Home Army cell. They all embody a world and values that are dying in the face of the silence of the Absolute. Religious symbols or lofty ideas appear in The Third Part of the Night in a distorted form, confronted with the brutality of the world, on the brink of annihilation – like the discussions on literature and philosophy futilely held by lice-feeding men, highlighting the spiritual emptiness surrounding people. The feverish existential tremor that constitutes the film’s matter is an attempt by a mind consumed by illness to escape this emptiness, floundering in search of meanings and remnants of ideas. Everything, however, seems alien, uncertain, and rotted through. It is hard to say even whether these chaotic spasms of the protagonist are a primal desire to survive or an increasingly desperate craving for death. The fragmentation of this world, its impenetrability, is something profoundly, at the most subconscious level, terrifying.

The Third Part of the Night can be read as a dark, apocalyptic ritual evoking the subjective experience of an extreme situation. Żuławski locates the essence of this experience in the fever that drives the film. The transgression of soul and body it causes paradoxically infuses empty symbols with an organic sense of dying, elevating death to the rank of the only attainable absolute for humans. The role of the priestess in this terrifying mystery is played by the main female character – Helena/Marta, who, in her duality, catalyzes both sexual vitality and mortal coldness. Her paleness and calm, which instantly shift to frenzied overexpression, intensify the horror of the situations that she draws Michał into, escalating his alienation and schizophrenic sense of loneliness amidst the jungle of voices and faces. Played by Małgorzata Braunek, the woman thus becomes the embodiment of the only significant force present in The Third Part of the Night – the eros-thanatos element of destruction leading to the brink of madness. However, in this perverse transgression, fulfillment is missing – death touches but does not completely annihilate, taking only part of what is due to it. Instead of completing the process of oblivion and finding eternal rest, Michał constantly experiences unfulfilled decay, sinking into an abyss of fears and paranoid delusions.

This is all filmed by Żuławski in a virtuoso style, combining the grotesque abstraction of dark colors and cold contrasts with the frenzied expressiveness and chaotic dynamics of individual sequences. The “playing” of wartime Lviv by Kraków is gray and profoundly grim, and when light occasionally illuminates the frames, it is pale, almost dead, casting an unsettling glow on the weary faces of the actors. Żuławski deftly transitions static scenes, imbued with metaphysical inspiration, into jittery passages, extracting surreal blurring of the boundaries between cruel reality and ghastly delusion from the realistic portrait of wartime Lviv’s daily life. Daring motion shots sit alongside strikingly composed visual metaphors, and exaggerated facial expressions with inspired monologues. Everything is seemingly contradictory, unreal, but simultaneously terrifyingly believable. The effect is not only an antithesis to heroic war cinema but also a brutal exposure of the real madness of the individual in the face of horror. In the Żuławski family memoirs, the fever caused by lice was a natural and inseparable element of the occupation experience; for viewers, it becomes a convincing and fertile hyperbole of war viewed from the perspective of a single person besieged by such a situation.

The Third Part of the Night, as openly surreal cinema, is not an easy watch. The viewer may at times feel lost in this tangle of symbols and threads, and the director’s stylistic choices only heighten the sense of strangeness and not necessarily pleasant detachment from reality. However, all of this forms a coherent and consistent vision, beneath the disjointed and frenzied surface lies a strong message. By creating this existential-mysterious depiction of war as an experience of spiritual and bodily apocalypse, Żuławski did not choose half-measures and made a bold film that, to this day, impresses with its formal extravagance. The Third Part of the Night is, alongside the equally personal Possession, his best directorial achievement – unlike some of his later films, in this debut, he managed to find a shaky balance between his characteristic overexpression and content coherence, resulting in perhaps the most meticulously constructed puzzle of dramaturgical complexity and symbolism in his career.

Andrzej Żuławski’s film is an extraordinary work, extracting from trauma and the unrealized experience of the individual fundamental motifs of religiosity, spirituality, and existential fears. It is also one of the most spectacular and successful flights of fancy in Polish cinema, as well as one of the most original war films. A work that is aesthetically refined, rich in meaning, and continuously evokes both horror and awe. It is undoubtedly one of the visionary masterpieces of Polish cinema, or at least its more unconventional realms.