THE SILENT STAR. First Sci-Fi adaptation of Stanislaw Lem

From adventurous spectacles with large budgets to monstrous propaganda about aggressors from the Red Planet, which was a not-so-subtle allusion to the Soviet Union. Of course, the poor cinematographies of socialist states, recovering from the war’s devastation, turned to science fiction much later (although the Czech Krakatit by Otakar Vavra was made in 1947).

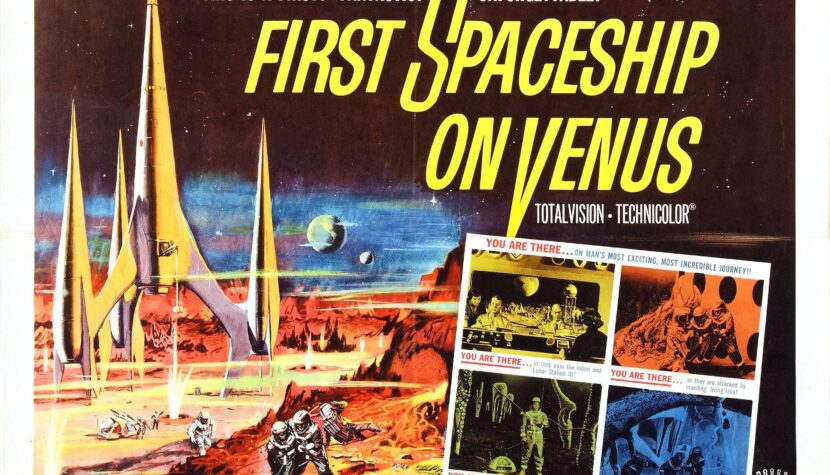

Several films, exploiting the most classic themes of SF literature, were produced in the Soviet Union in the 1950s. The cinematographies of other communist countries only began to flirt with science fiction in the following decade. Among the first to attempt this were fraternal artists from Poland and East Germany. The material for the screenplay of this prestigious co-production was provided by the first published SF novel by Stanislaw Lem, The Astronauts from 1951. The film, titled The Silent Star aka First Spaceship On Venus, was made in 1959, directed by a leading East German filmmaker, Kurt Maetzig. The scenes were shot in the DEFA studios in Babelsberg near Berlin, in the film studios in Wrocław, and near Zakopane. The premiere took place on March 7, 1960.

Why Lem? Firstly, the surname of the young writer was already widely known in Poland and abroad (although more due to the exoticism of the Iron Curtain and Khrushchev’s thaw). Stanislaw Lem was triumphing at the end of the 1950s with the adventures of Ijon Tichy in The Star Diaries, and he had already published The Magellanic Cloud and Eden, with Return from the Stars and Solaris to follow in a few years. A well-known name in a joint, pioneering, socialist film production was an additional advantage. Secondly, the theme of The Astronauts was extremely favorable from a genre perspective. Lem’s description of the first manned flight to Venus perfectly met the requirements of the first SF film production in Polish cinema. Why would our creators embark on an interstellar journey from The Magellanic Cloud when they first had to symbolically break away from Earth with a rocket and land much closer? World cinemas started with moon expeditions, based on the prose of Verne and Wells, which set an informal order of space flights for creators, slightly later beginning the exploration of the cinematic cosmos.

The creators of the film moved the action from Lem’s 2003 to the year 1970, closer to their own time. The triumphant, Soviet socialist economy successfully civilized the most inhospitable regions of the country. International cooperation, which established permanent bases on the Moon, is progressing successfully thanks to socialist countries. During work in Siberia, a piece of metal completely unknown to humanity was found, a remnant of the Tunguska meteorite from 1908. Engaged in the work were teams of scientists and electronic brains who, after calculating the presumed trajectory of the meteorite, concluded that the piece of metal was a remnant of a Venusian spaceship that crashed on our planet. This led to the decision to undertake the first interplanetary manned flight to Venus. The crew of the spaceship “Cosmocrator” was composed of representatives from Japan, the USA, Poland, the USSR, India, Germany, China, and one from an African country. The astronauts, expecting to see an advanced, thriving Venusian civilization beneath the cloud cover, instead saw the blackened, radioactive ruins of Venusian technology, turned to rubble. The conclusion was obvious – the inhabitants of Venus had planned an invasion of Earth, but meticulously amassed arsenal was used in a fratricidal war…

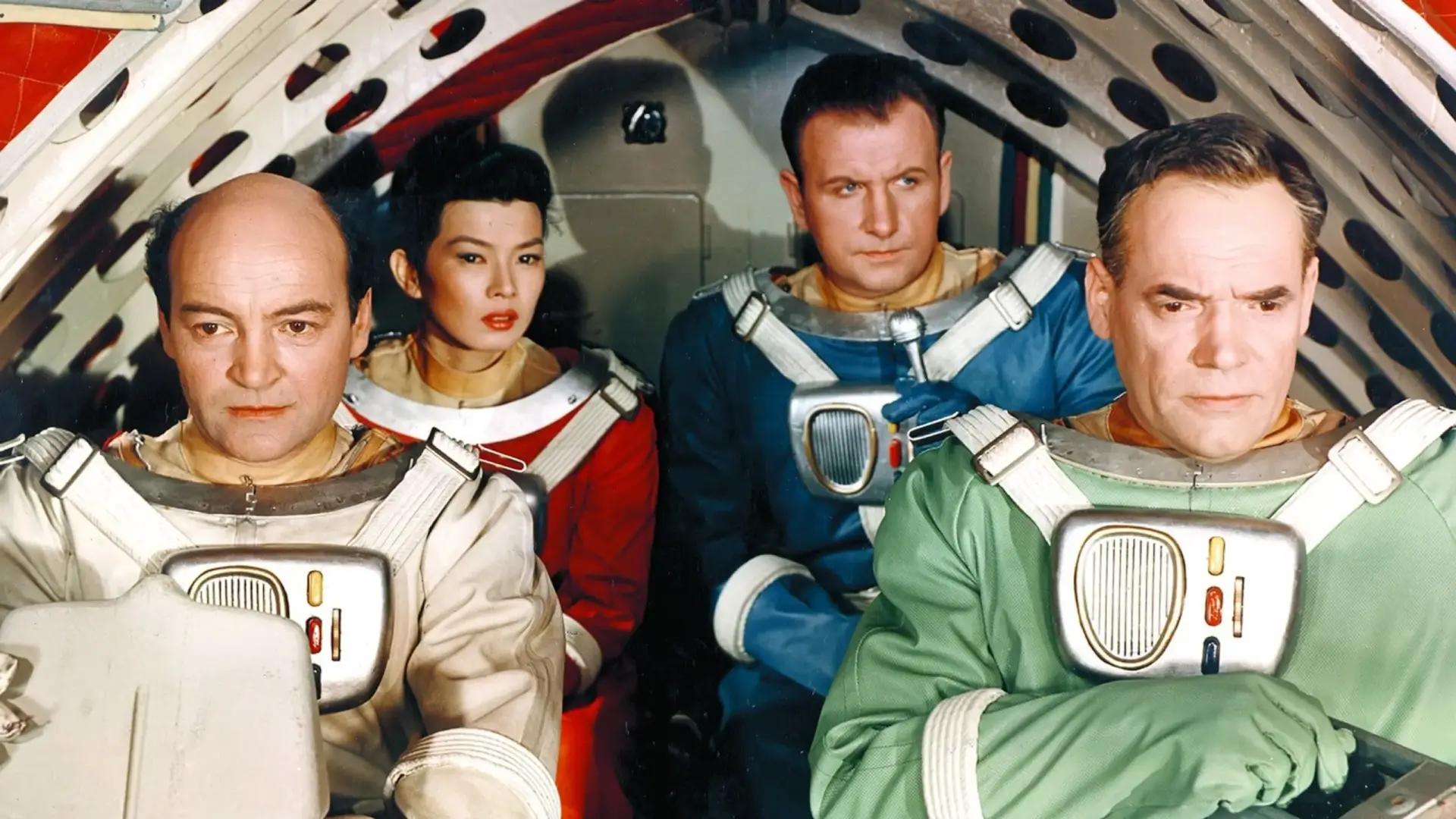

Stanisław Lem repeatedly emphasized that the ideological hymns to the only correct communism sprinkled throughout the novel were treated solely as a showcase servitude for the authorities during writing, so that his work would meet the statistical norm of correctness. The screenwriters of The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus wisely abandoned the outdated, socialist-realist veneer. In the novel, all atomic evil is attributed to bloodthirsty capitalism; the film departs from these absurdities in favor of the then-current appeal for the disarmament of atomic powers. The idea is noble, but its presentation on screen is another confirmation of why Stanisław Lem dislikes adaptations of his novels so much. Instead of directing the actors properly, Kurt Maetzig placed before the camera figurines molded from lofty ideas, drenched in a thick, indigestible, moralistic sauce. The characters on screen are devoid of life and energy, not to mention wit or self-irony. Particularly targeted is Yoko Tani in the role of the attractive Japanese doctor, with a perpetually suffering expression, a remnant of the traumatic events of Hiroshima and the death of her husband on the Moon.

The acting in The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus is a textbook example of “academy in homage with artistic demonstration.” The result of such direction (or rather its absence) is the viewer’s almost complete indifference to whether our heroes will return safely from Venus or not. In this international stew, fortunately, there was only one Polish actor, Ignacy Machowski, in the role of the onboard engineer (many years later he played Kasia Piorecka’s father in Stanisław Bareja’s series Zmiennicy). Among the native artists in supporting roles, Lucyna Winnicka appears on screen as a journalist from Interwizja. It was already quite extravagant of Maetzig, as this outstanding actress, with a whole bunch of great roles in Polish cinema, practically played just a pretty ornament and nothing more in The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus.

The visual side of the film is a true museum of SF imagination, which could only impress contemporary viewers. It confirms the old rule that the scenery in science fiction films ages the faster the more modern it wants to look. For a contemporary viewer, the interior of the “Cosmocrator” is a kitsch that is hard to take seriously without a smile on one’s face. The electronic brain of the ship, named Marax, can perform an astonishing five million operations per second. Onboard devices consist of obligatory sets of flashing lights or screens displaying abstract patterns. When I watched it, it suddenly dawned on me where the creators of the old, though still charming, television program Visitors from Matplanet got the view of the computer speaking to Sigma and Pi. In one of the scenes, weightlessness is also shown. Unfortunately, the seat belts are clearly visible on equally visible wires.

But speaking seriously, it must be remembered that The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus was essentially a pioneering spectacle of SF in communist cinema. Empathizing with the viewer from over 60 years ago, it must be clearly stated that the vision of the splendid Polish set designer Anatol Radzinowicz (and the German Alfred Hirschmeier) must have made quite an impression. The Venusian landscapes, the bizarre constructions covering the surface of the destroyed planet, were outstanding achievements for those times, as were the interiors of the “Cosmocrator.” No one has such an idea of decor for an SF film anymore, but cosmic fantasy had to mature thanks to such attempts by screen artists of bygone years.

Moreover, comparing the visual appearance of The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus with the look of the Star Trek series, the production of which began in the USA five years later, one can conclude that our imaginative artists lacked nothing, and despite the civilizational delay, the scenic visions on both sides of the Iron Curtain were at times remarkably similar. Since we are comparing the East with the West, the special effects in The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus were, for those times (and technical capabilities), quite advanced. The optical merging of miniature shots with live action was done flawlessly; only the use of miniature cosmodrome decorations screams of naivety and lack of credibility. The Oscar-winning effects by Wah Chang and Gene Warren for The Time Machine, made in the same year in the USA, surprisingly do not seem more advanced. Several American critics even wrote that The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus is the best-looking cosmic SF film of those years produced outside Hollywood.

The Silent Star in two editing versions (81 and 99 minutes), of which the longer one circulates with not always confirmed information. The Americans, preparing the film for distribution in the USA (under the title First Spaceship on Venus), made many drastic changes, including changing the nationalities of most crew members to American and removing all references to the Hiroshima tragedy. The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus opened a series of adaptations of Stanislaw Lem’s prose, continued by Andrzej Wajda (Layer Cake), Andrei Tarkovsky (Solaris), Marek Piestrak (Pilot Pirx’s Inquest), or even Steven Soderbergh and James Cameron, making the third adaptation of Solaris. Kurt Maetzig’s film is certainly weaker than all those mentioned. Stanisław Lem bluntly described it as the “bottom of the bottom” and “muddled, socialist-realist pastiche.” Well, Master from Krakow never minced his words, although on the other hand, he himself sold the rights to adapt his novels to people who probably shouldn’t have done it…

Currently, The Silent Star / First Spaceship On Venus is characterized only by its unique and difficult-to-replicate atmosphere of old, naive SF cinema, appreciated perhaps only by ardent fans or genre historians. It is also certainly one of the most difficult-to-obtain films based on Lem’s prose (although it is available in foreign online stores, unfortunately only with German dubbing and without subtitles). I acquired it by accident, from Jan Sladecek, a Czech SF film fan (many thanks!), who, incidentally, only had its German-language version, recorded from the German MDR television…