THE LAST DAY OF SUMMER. Can one love after the war?

Masterpieces such as Kanal and Man on the Tracks (both 1956), and Eroica (1957) had premiered; October 1958 was to be marked by perhaps the most legendary of Polish films — Ashes and Diamonds. However, two months before this milestone of native art reached cinemas, a much more modest work was released, initially receiving incomparably less acclaim.

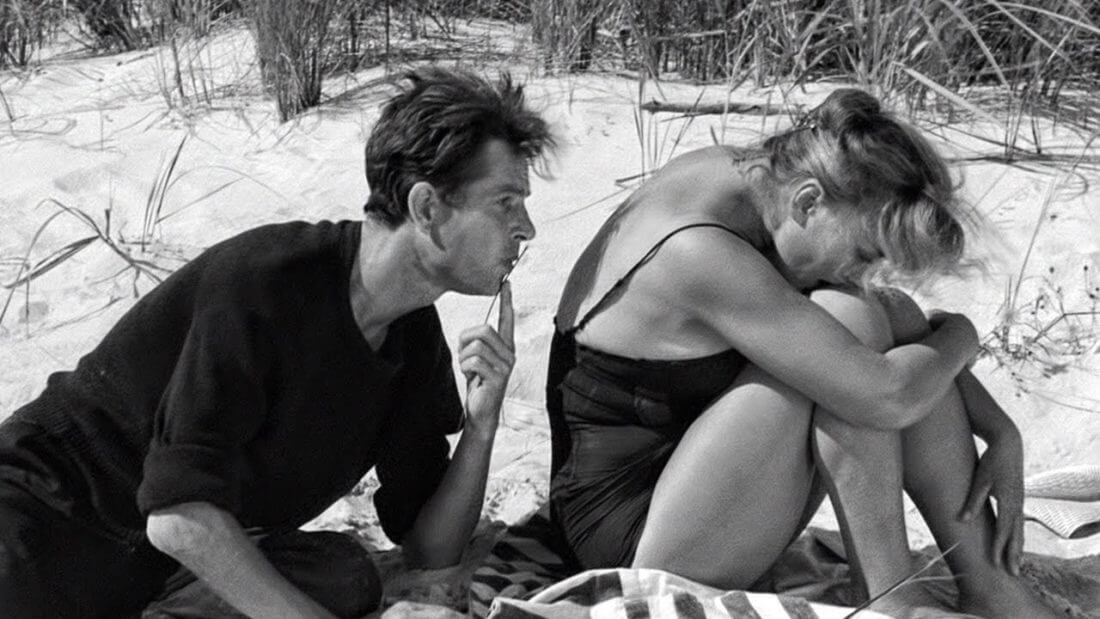

Fortunately, over time, this changed, and Tadeusz Konwicki‘s The Last Day of Summer can today be placed alongside Andrzej Wajda’s work. All it took was two actors, a deserted beach in Szklana Huta, and the creator’s unique sensitivity.

At that time, Konwicki did not occupy a particularly prestigious place in Polish art. The young artist was primarily known as a writer of literature belonging to the fading socialist realism. As a filmmaker, he had practically no experience — his only notable success was the screenplay for the excellent Winter Twilight (1956) by Stanisław Lenartowicz. Thus, Konwicki could not count on special trust in realizing his directorial debut. To finance The Last Day of Summer, the artist received the whopping sum of… ten thousand zlotys. This did not dampen the young director’s enthusiasm, and the ridiculously low budget was not an obstacle to realizing the work. One could even say it suited the intimate nature of the entire film, which did not require large sums, and the production limitations might have even been somewhat advantageous for Konwicki, providing him with the psychological comfort a novice creator might not have experienced working on a large project. To this day, The Last Day of Summer remains the cheapest film in the history of Polish cinema.

The outline of the plot can be summarized in a few short sentences. A nameless boy (Jan Machulski) meets a woman (Irena Laskowska) on a deserted beach. He has special feelings for her, but she resists getting too close. Both try to reach each other while also dealing with traumas that make it difficult. That’s it, but Konwicki didn’t need more to create a cinematic masterpiece. Because in The Last Day of Summer, it’s not about a specific plot but about these two characters. Although the film is classified as part of the Polish Film School, it does not form its thematic and stylistic core. That core usually consisted of stories about World War II, about struggling with its demons, whether during the conflict or immediately after its end. Konwicki took a different path. Here, the war is present, but in the minds and hearts of his characters. The Last Day of Summer is not a war film, openly reckoning, but primarily existential and psychological, centered on the human interior. Wounded, devastated, empty. With unhealed wounds that refuse to close.

As Tadeusz Lubelski noted, The Last Day of Summer was a therapeutic film, both for Konwicki himself and for the Polish audience marked by the war’s stigma. The film’s characters represent two generations bearing this mark. The boy belongs to the young, who after 1945 could not find themselves in the new reality, because the world of their childhood was gone forever, and they looked uncertainly into the future. The woman’s life also collapsed, but in a different way — she lost her beloved during the war, for whom she had waited faithfully. With his death, everything that constituted her existence died; perhaps for this reason, she feels already somewhat dead herself.

These two meet on a deserted beach, and their rendezvous can be interpreted in many ways. Because one of the greatest advantages of The Last Day of Summer is its perfect ambiguity. It can be seen simply as a love story between a young, somewhat naive boy and an older woman. Konwicki, along with cameraman Jan Laskowski, through long, static shots interspersed with slow movements, gives the two actors a chance to shine, which they utilize excellently. In The Last Day of Summer, there aren’t many dialogues because everything important happens between the words, in the looks of Machulski and Laskowska, in their gestures and expressions. If we want to see the film as a summer romance story, it will be just as poignant and sincere as when viewed through the lens of something completely different.

It gets more interesting when delved into deeper. Psychologically, The Last Day of Summer is a film about the attempt to rebuild oneself by two people who cannot love, fearing closeness because it might end in loss, pain, misunderstanding. They want to fill the void in their souls, but it’s not an easy task. One way or another, the issue of occupation returns, subtly suggested by Konwicki through the sounds of airplanes occasionally flying over the couple’s heads. Because the stigma of the past war constantly weighs on the lovers, and although in an existential interpretation, there is universal space for unprocessed trauma, The Last Day of Summer clearly suggests what it really is — the memory of hell. It is still an unhealed wound that prevents people from finding themselves in the present; in their minds, they still hear grenade explosions, and they react to an outstretched hand by withdrawing, thinking it is not for an embrace, but a blow.

Regardless of how one looks at it, Konwicki allows himself and his actors delicacy, contemplation, and poetic ethereality. The director sets a slow pace, observing not only the characters themselves but also the silent emptiness that surrounds them. In The Last Day of Summer, the viewer can immerse themselves in this dreamlike atmosphere, attune to this rhythm, pulsating not with action but with the beating of two hearts reaching out to each other and uncertain glances, full of both hope and fear. Konwicki masterfully directs Machulski and Laskowska, whose retreats and hesitations can equally be expressions of shyness caused by an emerging, unexpected feeling as well as fear of potential harm. Their joy, always tinged with fear, even when it begins to blossom, quickly subsides, giving way to a cold retreat into themselves.

When discussing the New Wave in Poland, a few films gradually moving away from the Polish Film School’s poetics are usually mentioned, and the nascent movement appears as wasted potential, curtailed by the intervention of the censorship apparatus. However, before Roman Polanski made his Knife in the Water (1961) and Jerzy Skolimowski his Identification Marks: None (1964), it was The Last Day of Summer that reached for New Wave poetics, roughly at the same time as the most famous of the European New Waves — the French one — was forming. The audience in 1958 did not quite know what to make of Konwicki’s work. This withdrawn, non-narrative, contemplative film did not win the sympathy of the officials at the Chief Directorate of Cinematography, and only a fortunate twist of fate ensures that we remember it well today. The Last Day of Summer was sent to the Venice Film Festival almost by chance, where it won the Grand Prix in the category of short or documentary film. This success immediately elevated the film’s status in the eyes of the Directorate’s officials, allowing Konwicki’s production to reach cinemas.

Today, The Last Day of Summer is considered one of the most important films in Polish cinematography overall, and at the same time one of its most interesting debuts. Tadeusz Konwicki was perhaps the first to use New Wave poetics in Poland, which, although it did not last long here, perfectly matched the film’s character. And this film, despite its ambiguity, primarily turned out to be a self-therapy for Polish society, which, like the unhappily in love protagonists, needed to be reborn and experience post-war catharsis.