SILENCE: Oppressive, Heavy, and Visually Stunning

The 1966 book Chinmoku by Shūsaku Endō became a major artistic success—widely analyzed for its religious ambiguity and quickly absorbed into other areas of culture. It inspired not only a stage play, a symphony, a libretto, and an opera but also adaptations for the screen. Naturally, the first adaptation came from the Land of the Rising Sun, where a film of the same title was released just five years later. More than two decades later, the Portuguese also turned to the book, creating Os Olhos da Ásia (The Eyes of Asia), though that production went largely unnoticed. A bit earlier, the story of 17th-century Japan as seen through the eyes of Jesuit missionaries caught the attention of none other than Martin Scorsese, fresh off his similarly themed and controversial The Last Temptation of Christ. However, Scorsese had little luck with this new project, Silence, which took nearly three decades to complete and ultimately floundered at the box office.

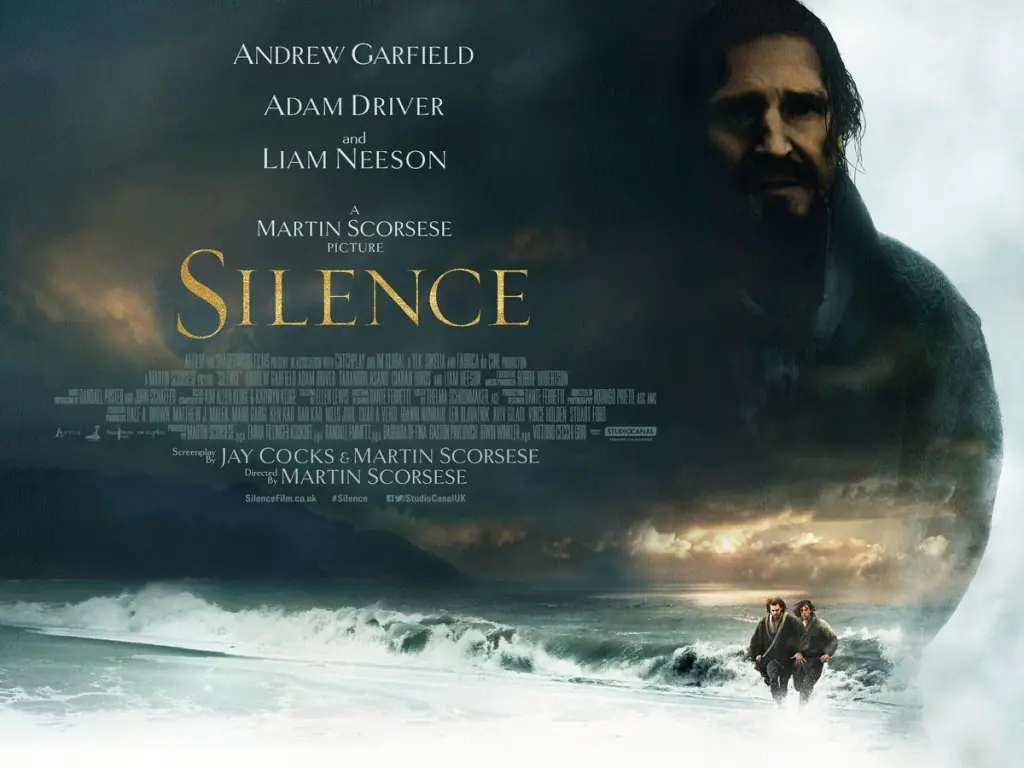

The story’s premise—based on historical facts only slightly altered by Endō—bears some resemblance to Apocalypse Now (though the author was reportedly also inspired by La Strada). In the bastion of Portuguese Christianity, word arrives that Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson, returning to themes reminiscent of The Mission after nearly three decades), who oversees a mission in distant Japan, has renounced his God and is therefore lost to the cause. Two of his former protégés—Fathers Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield, once again taking on a martyr-like role) and Garupe (Adam Driver)—are sent to find him and salvage the mission. Relying on vague, outdated reports, they venture into an isolated country embroiled in a true war, not knowing what awaits them or what has become of Ferreira. Thus begins not only a journey into the heart of darkness but also into the depths of their own souls.

According to various accounts from those involved in the production, Silence is both the most challenging (primarily due to the weather conditions in Taiwan, where it was filmed) and the best film of Scorsese’s career. At least, that’s what producers Irwin Winkler and Emma Tillinger Koskoff claim. They’re echoed by Neeson, who admitted in an interview that during their second collaboration (after Gangs of New York), Scorsese could be intensely unpleasant, even terrifying. Neeson also lost nearly ten kilograms while playing Father Ferreira, as did Driver, who shed over twenty kilograms during the shoot. Add to this the numerous casting changes over the years—Neeson’s role was initially intended for the inimitable Daniel Day-Lewis, with other parts slated for Gael García Bernal, Benicio Del Toro, and Ken Watanabe—and the endless delays in starting production, scheduling, and securing funding, and a grim picture of the project’s development emerges.

All of this translated into the final product, which is undoubtedly engaging but also exhausting to watch, challenging to interpret, and painfully personal. The nearly three-hour fresco (originally, the material reportedly ran to 195 minutes) can at times feel tedious, drawn-out, and monotonous. It’s no surprise, then, that with a modest $40 million budget, it turned out to be a financial failure. Poor marketing didn’t help—promotion began just a month before the premiere, and the film didn’t enter general distribution until January, which also contributed to its artistic underperformance, a fate it certainly did not deserve.

In some ways, this is a fascinating work that hypnotizes with its ascetic nature and minimalist form and content.

The subject matter alone is already uncomfortable, as Scorsese delves into religion and its significance in human life. The filmmaker, who dedicated the piece to his family and first screened it in the heart of Christianity—the Vatican—is well-versed in the topic. This is not only due to his Italian heritage and earlier works on the subject (such as Kundun) but also because he once attended a seminary and, before fully committing to cinema, seriously considered becoming a priest. As a result, Silence is devoid of platitudes or ethically dubious discussions about one religion versus another. While there is a touch of kitschy symbolism, the director—co-writing the screenplay for the first time since Casino—keeps everything under control, at times teetering on the edge of excessive subtlety.

That said, religion here is essentially just a backdrop. Scorsese shows little interest in Christianity or Buddhism or the philosophies behind them. While we observe certain rituals characteristic of both sides, see their typical elements, and hear specific phrases from their followers, we don’t learn anything new about either faith, nor do we delve into their essence. If not for the historical context, the religions could easily be replaced by any other cult. The key to understanding them here lies in faith itself—what drives it, how strong it can be in an individual, how far one can go for it, and how much one can sacrifice for it. Despite the evocative final shot, Scorsese examines the events and his characters with an almost documentary-like detachment, avoiding a black-and-white division into good and evil.

The Asian aggressors are admittedly drawn with broad, almost caricatured strokes—as in the case of the elderly Inoue, played by Issei Ogata, who could double as a comic book villain. This, combined with their brutal treatment of victims, automatically casts them as the antagonists. However, their actions, morally ambiguous and sadistic as they may be, are not mere whims. Moreover, their reasoning is entirely believable and can easily be applied to other eras and cultural-religious clashes that ended in various purges. It’s an age-old truth about the impossibility of understanding across divisions and prejudices—depicted by Scorsese with the skill of a true master.

On a fundamental level, Silence is an incredibly beautiful, visually stunning work.

This is due in large part to the irreplaceable Thelma Schoonmaker (with her practically invisible, perfect editing), the austere, contemplative score by Kathryn and Kim Allen Kluge, previously unknown to wider audiences, and the picturesque cinematography by Rodrigo Prieto (The Wolf of Wall Street, Passengers)—the only member of the crew to receive an Academy Award nomination.

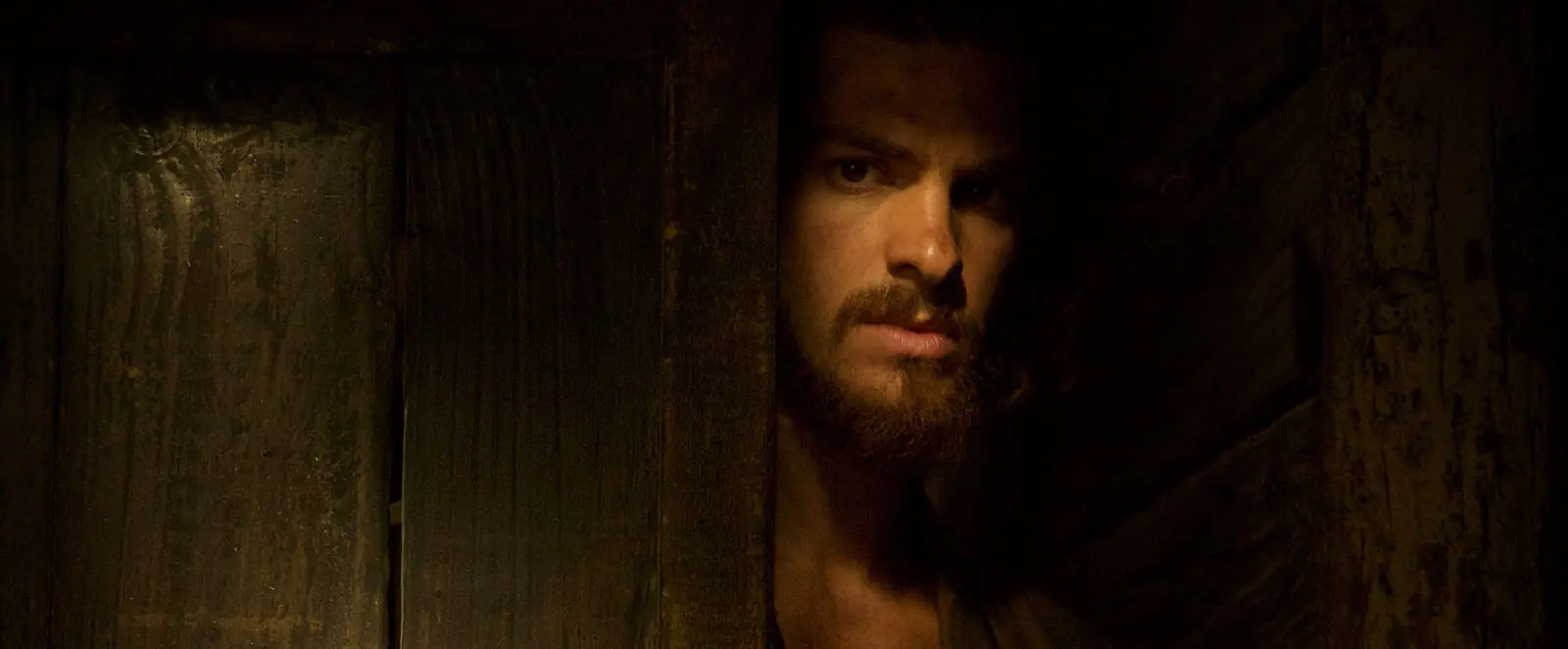

However, the real driving force of Silence lies in its outstanding performances. This applies not only to the leads, with perhaps Garfield’s best performance of his (still young) career, but also to the farthest reaches of the cast (where Ciarán Hinds appears in a brief role)—especially the Asian ensemble, led by the aforementioned Ogata, Yōsuke Kubozuka (the drunken Kichijiro), and Tadanobu Asano (the cunning translator).

Sometimes, silence is the deadliest sound. That’s the film’s tagline, and the creators took the title to heart. The slow pacing, relationships between characters built on simple dialogues, glances, or other nuances; ethereal music enhanced by the sounds of crickets or the rustling wind; gloomy weather amplifying the dominance of cold tones (with the presence of fire filling the frame with warmer hues)—all contribute to a film where much happens, but never too quickly. Emotions run high, but they rarely explode outright. Tears are lost in falling rain, and screams are drowned out by waves crashing on rocky shores. Stoic calm is maintained even in numerous acts of violence, which appear disturbingly aesthetic, like living works of art. Paradoxically, it’s this conspiracy of silence, sadistic persistence, and consistent self-destruction that electrifies the most.

It’s incredibly difficult to definitively assess Scorsese’s film because, contrary to appearances, it defies categorization or neat labels. It’s undoubtedly a good, meticulously crafted, high-caliber work of cinema. But it’s also a film that grows on you over time. It’s specific, deeply artistic, sometimes even poetic—in short, it’s for the patient viewer. This is not a film one revisits often (if at all) or fondly remembers or casually recommends. Despite its faint glimmer of hope, Silence doesn’t offer spiritual solace or satisfying conclusions. It’s oppressive, heavy, and even mentally exhausting—a film where the devil is in the details, and its power lies in its expression and the precision of its message.