CASINO Explained: The True Story Behind Scorsese’s Movie

Goodfellas instantly captivated both audiences and critics. In numerous prestigious year-end rankings for 1990, the film claimed top spots, and Roger Ebert even called it one of the best, if not the best, gangster films in cinema history.

The American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences also recognized the film, though Goodfellas losing to Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves remains one of the most frequently cited, biting anecdotes used to poke fun at the choices made by the Oscar jury. While Cape Fear (1991) didn’t receive such unanimous praise, it nonetheless solidified Scorsese’s already formidable reputation, which wasn’t even dented by the lukewarm reception of The Age of Innocence. After that, it was time to return to the gangster underworld, and Scorsese directed Casino.

The story of gangsters controlling the American El Dorado—Las Vegas—inevitably faced comparisons with the brilliant Goodfellas. The themes of both films were too similar to avoid lengthy comparisons. Many accused Scorsese of repeating himself, telling the same story again. However, from today’s perspective, this critique seems unfair. While there are indeed many similarities between the two films, including the same actors, a deeper reflection reveals fundamental differences that make any accusations of self-plagiarism baseless.

This City Will Never Be the Same

It’s difficult to talk about Las Vegas in the context of Casino because the story told by Scorsese has a certain poetry. The Italian-American director is one of the few filmmakers who can spend an hour meticulously explaining to the audience how the phenomenon that supposedly serves as the backdrop for the main characters’ lives actually operates. It’s like James Cameron spending several minutes showing us the inner workings of a shipyard and an office before the Titanic sets sail, explaining the ticket sales policy and the reasoning behind specific structural elements. The mastery with which Scorsese handles the narrative is simply dazzling. The characteristic freeze frames, tracking shots, whip pans, and obsessive attention to detail elevate the film from a mere guide for novice gamblers to a cinematic masterpiece. This elongated prologue also clearly signals who the real protagonist of the story is this time—and it’s not Sam Rothstein or even Nicky Santoro, but Las Vegas itself. The neon lights of the gambling kingdom overshadow the character portraits because that’s precisely how Vegas works, a place where hundreds of stories worthy of being told unfold daily between the roulette table and the bar.

In Goodfellas, there’s a notable ironic distance, especially in the epilogue, framing the film with the sentiment: Since I was a kid, I wanted to be a gangster. I made it, but it turned out that the gangster life isn’t as glamorous as it seems, though it’s hard to say if living a mundane suburban life isn’t worse. Scorsese thus mythologizes the mafia, playing with childhood fantasies about it, shaped by growing up in New York’s Little Italy. At first glance, Casino seems to use a similar approach. As long as things are going well, life for someone entangled in mafia dealings can feel like a paradise. But once one domino falls, the rest follow, triggering a chain reaction that takes a bloody toll, destroying lives and futures. However, the epilogue in which De Niro’s character reflects on the changes that occurred in Las Vegas after the successful police crackdown on mafia control over the casinos is starkly different from the one delivered by the protagonist in Goodfellas.

In the finale of Casino, there’s no humor or ironic smile. Part of this is due to nostalgia for what has passed (as in Goodfellas), but it’s also because Scorsese, through Rothstein, subtly questions what happened to Las Vegas after this crackdown. He wonders whether the corporate control of gambling by wealthy financiers differs all that much from the days when mafia bosses ran the show—and whether it was more natural when classic criminals were the ones cheating people, rather than a group of suit-clad individuals exploiting connections, weaknesses in the system, and the capital they had amassed. The era of Rothstein and Spilotro has passed; the age of the Wolf of Wall Street has begun.

It’s on this level that the fundamental difference between Goodfellas, which focuses primarily on telling the story of specific characters, and Casino, which uses the characters’ lives to explore the mechanisms governing Las Vegas and the changes that occurred in one of America’s most iconic cities during the 1970s and 1980s, becomes clear. It’s not so much a story about individuals as it is about the time and place in which they’re entangled. Scorsese’s directorial prowess ensures that the viewer doesn’t experience a sense of dissonance from this structure. This is because Rothstein, Santoro, and Ginger are, in essence, personifications of Las Vegas itself, embodying its full range of characteristics. Their evolution and downfall are inextricably tied to the transformations happening in the gambling capital.

Behind the Scenes at the Casino

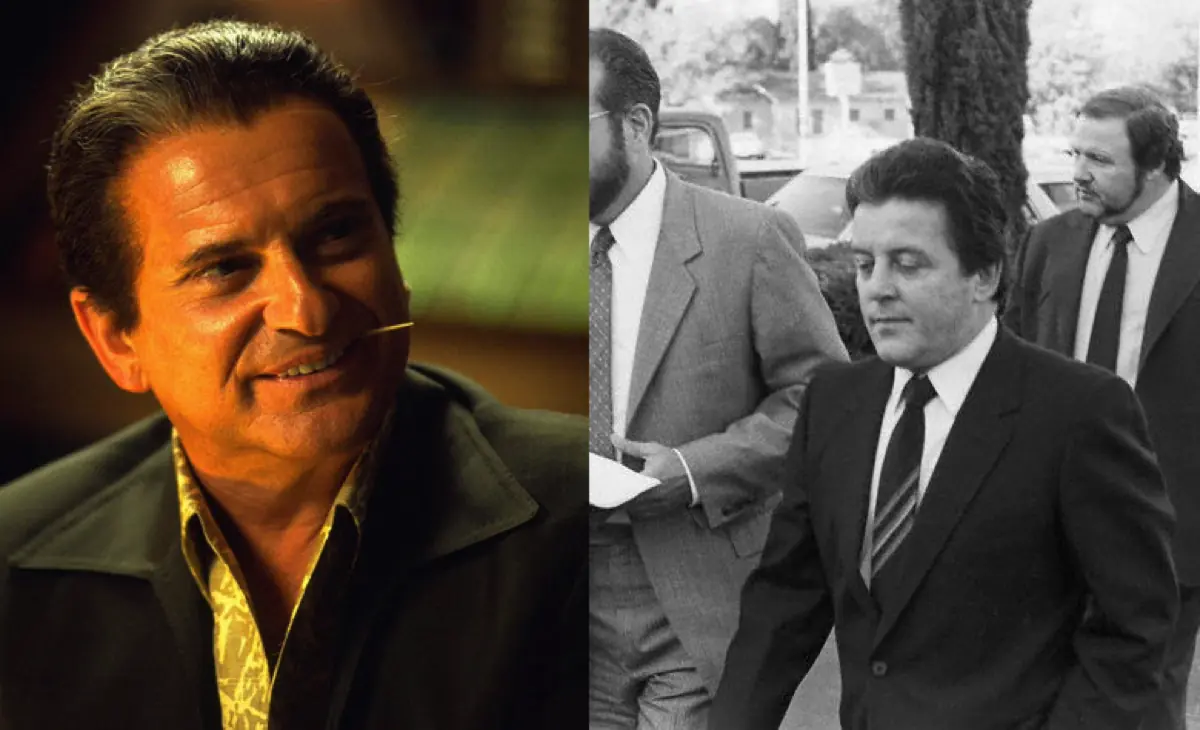

The directorial mastery on display in Casino cannot be overstated. However, it’s important to remember that the film’s screenplay was co-written by Nicholas Pileggi, based on his book Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas. In it, Pileggi tells the story of two prominent members of the Chicago mafia—Frank Rosenthal and Anthony Spilotro. By systematically detailing the stages of their operations in Las Vegas during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Pileggi uncovers the criminal underpinnings of the highly profitable casino business. The author’s journalistic work was made easier by his access to Rosenthal himself, who, like the film’s Sam Rothstein, survived a car bomb explosion and managed to escape the tightening noose around the leaders of the gambling scene that controlled the city lighting up the Nevada desert. Robert De Niro’s character is, in Scorsese’s world, the equivalent of Frank Rosenthal, while Anthony Spilotro transforms into Nicky Santoro in Casino. Watching the Hollywood production, it’s worth keeping in mind that the story told by the director and screenwriter represents a significant piece of American criminal history.

Rosenthal was indeed noticed by the mafia as an exceptionally talented bookmaker who could make significant amounts of money from sports betting. Initially, his operations were not on a large scale, but the people pulling the strings within the criminal organizations appreciated his caution and ability to calculate risks. Thanks to these traits, he managed to avoid drawing much attention from the police until the 1960s. Even more impressively, he earned a reputation among gamblers as a specialist in bookmaking. However, ambition grows with success—once Frank began associating with individuals already on the FBI’s radar, more and more investigative leads in Miami, Rosenthal’s first area of operation, started to point toward his doorstep. In 1968, the bookmaker moved to Las Vegas, where, under the guise of legitimate business, he was tasked with managing four casinos—Stardust, Fremont, Marina, and Hacienda—using his organizational skills. Under his supervision, these gambling establishments significantly increased their profits, which naturally pleased the mafia representatives. To protect Rosenthal from those hostile to this success, the bosses decided to bolster his security. Back in 1964, during his time in Miami, a similar move had yielded good results. Rosenthal’s protection was entrusted to Anthony Spilotro, who lived in Chicago and had known the bookmaker since childhood. In 1971, the man responsible for eliminating potential threats to the business arrived in Las Vegas. But this time, things began to spiral out of control.

Spilotro quickly became too greedy, which significantly worsened Rosenthal’s situation. Aside from starting his own ventures and openly engaging in criminal activities that attracted the attention of the local police, Spilotro was banned from entering any gambling establishments. He was also linked to murders, including the killing of Chicago real estate agent Leo Foreman, who was murdered by Spilotro’s colleague Sam DeStefano in a way eerily reminiscent of the famous bar murder scene from Casino. Before being shot in the head, Foreman was stabbed with an ice pick, which DeStefano used to tear pieces from his body, just as Joe Pesci’s character used a pen in the bar scene.

After being banned from casinos, Spilotro became even more involved in robberies, forming a gang in Nevada known as The Hole in the Wall Gang. The group became infamous for burglarizing businesses by drilling through walls, particularly in jewelry stores. The gang was dismantled in 1981. By this time, Spilotro’s and Rosenthal’s relationship had turned from friendly to decidedly hostile. Contrary to what one might expect, their falling out wasn’t solely due to Spilotro’s criminal activities, though that certainly played a role, but rather the fact that Spilotro had an affair with Rosenthal’s wife, Geraldine McGee—depicted as Ginger McKenna in the film. Like Sharon Stone’s character, McGee married the enamored Rosenthal, bore him two children (in the film, one), and was unable to escape her addiction to drugs and alcohol, which—after their divorce—led to her death in the hallway of a cheap motel.

A year after the gang’s dismantling, Rosenthal’s car exploded in Las Vegas. He survived thanks to the fact that a few months earlier, he had purchased a Cadillac Eldorado, which, to improve its geometry, had been factory-fitted with a thick metal plate under the chassis. This plate absorbed the force of the blast, giving Rosenthal the chance to later tell his story to Nicholas Pileggi. A month after the explosion, Rosenthal left Las Vegas and moved to California. In 1987, he was officially banned from returning to the city. Spilotro’s story ended the year before. He and his brother were lured by the mafia to a house where they were brutally beaten nearly to death in the basement. Their bodies were buried in a cornfield along U.S. Route 41. The era of mafia dominance over Las Vegas casinos, which attracted millions of tourists, officially came to an end. A broad police operation, culminating in the so-called Operation Pendorf, sought to prove once and for all the connections between criminal organizations, casinos, and state-run companies. The primary target of the police investigation was Allen Dorfman, who in Casino became the character Andy Stone.

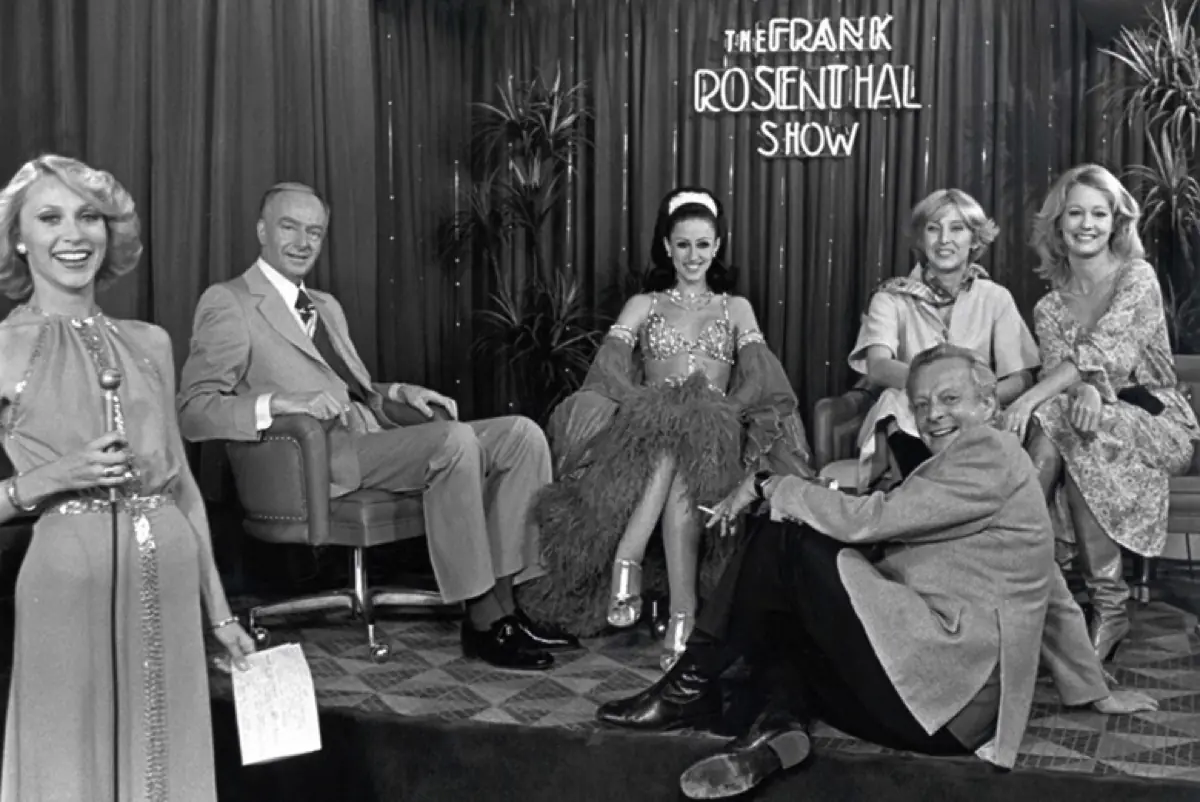

Scorsese’s engagement with history doesn’t stop with the main plotline of Casino. Several scenes in the film reference specific events that, in one way or another, relate to the story of the mafia’s downfall in the gambling empire. In 1977, Frank Rosenthal indeed launched a TV show bearing his name, where he acted as the host. These efforts were likely aimed at improving his public image and distancing himself from Spilotro’s activities. The Asian gambler who appears in one scene, initially winning a small fortune at the casino only to lose it due to a canceled flight, is based on Akio Kashiwagi, a frequent guest of Las Vegas in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Like the film’s K.K. Ichikawa, Kashiwagi played high-stakes games, which eventually led to his bankruptcy and massive debt. It’s highly probable that these debts led to his murder in 1992 by members of the Japanese Yakuza.

The infamous torture scene involving Nicky Santoro and a vise, which was censored in countries like Sweden, refers to the beginning of Spilotro’s criminal career and the so-called M&M Murders of 1962. To win favor with the mafia, Spilotro killed the men responsible for murdering the Scalvo brothers, who were associated with the Chicago mob. The brutal torture depicted in Casino mirrors the method Spilotro used to deal with Bill McCarthy. For three days, McCarthy was beaten and mutilated, and an ice pick was driven into his groin. Ultimately, McCarthy revealed his accomplice’s name after having his skull crushed in a vise. After McCarthy begged for death, Spilotro doused his body in lighter fluid and set it on fire. Such references abound in Casino, leading us to somewhat humorously conclude that Martin Scorsese’s film is one of the most riveting documentaries in cinema history.

For a long time, Casino remained in the shadow of Goodfellas, and even today, it has not entirely shaken the burden of its predecessor’s greatness. This is deeply unfair, yet that’s how history works. If this film is viewed merely as a gangster variation on the 1990 movie, it deserves a second chance. Not only because it is an almost encyclopedic example of masterful filmmaking and superb acting, which is obvious, but because of the subtlety with which Scorsese can speak about change and the passage of time—regardless of the brutality of the world he portrays.