Stumped by the heel of a latex boot, or what to do with SHOWGIRLS?

Well, what to do with Showgirls?! The easiest thing would be to put a microphone under Paul Verhoeven’s nose and ask him about it in the tone of an intrusive journalist who likes to extract inconvenient facts from the past in order to provoke the interlocutor. The problem is that the director’s attitude towards Showgirls is intermittent, slightly bipolar and at least as shaky as the mood of Nomi Malone, the main character of this film.

Pure camp or just a failure?

Namely: Verhoeven sometimes claims that Showgirls is pure camp and that he was misunderstood, and sometimes he openly admits that the film did not work out because he couldn’t make it the way he wanted to (and in fact I suspect that it was left alone, without the producer’s supervision, he would have added more to the stove). Which position is closer to the truth? Well, both are contradicted by the graphic book by Verhoeven himself, accompanying the launch of Showgirls. In it, the director talks about his work as a serious, dark social drama that will surely shake the viewer and bring to light the rottenness of Hollywood – in short, he talks about a film from 1995, perhaps imaginary, but certainly not the one that then he shot.

His texts in the book are written too seriously to talk about a prank here, the other statements of the director accompanying the premiere are similar, and the actors also think similarly. When asked about his involvement in the film, Kyle MacLachlan replies that no one on set treated Showgirls as satire and that such an interpretation of the whole is an abuse. In interviews, the young Elizabeth Berkley talked with emotion about how strong and moving the film she plays the main role. Perhaps only Joe Eszterhas, the screenwriter, consistently sticks to the Showgirls defense as self-conscious kitsch. In his opinion, from the very beginning it was about the camp, about the swashbuckling retelling of All About Eve by Mankiewicz, but probably even he was not proud of the final result, since he had a deadly argument with Verhoeven after the failure of Showgirls – a film that was ultimately supposed to repeat the artistic and financial success of the previous project from both creators, Basic Instinct.

The director, writer and actors therefore do not know what to do with Showgirls. It’s hard, it doesn’t matter anyway, we’ve all mourned the Author’s Death in 1967. Maybe the critics will know? For a change, they were extremely unanimous right after the premiere, when they hailed Showgirls as the most monstrous film ever made, and showered it with The Razzies (personally received by the director!) first for the worst production of 1995, and then – the whole decade. Reviewers outdid themselves in the effective pouring of sloppy words on this film, which is sometimes really funny to read, and sometimes the texts from today’s perspective are disgusting with their overt misogyny towards 21-year-old Berkley. There is also in these first Showgirls reviews something of repulsive populism, of collective punishment and collective burning of the one whom everyone has already recognized as the weakest in the tribe and whom everyone must now ruthlessly hit, thus expressing their superiority, contempt and belonging to the herd of those who know better.

The turnaround in Showgirls’ reception begins with the title’s unexpected success on the VHS market. At the same time, the production began to gain the interest of queer audiences, who elevated the film to the status of an underground classic, eagerly recreating it as part of drag shows; Showgirls‘ uncompromising sexual expression resonated well with viewers who had to hide their sexuality in everyday life. Around the turn of the century, the first positive opinions of critics about the film began to clink timidly. They were: listen, are we sure we haven’t made a mistake? After all, Showgirls is just camp. Is this the worst movie in the history of cinema or is it more of an accidental masterpiece?

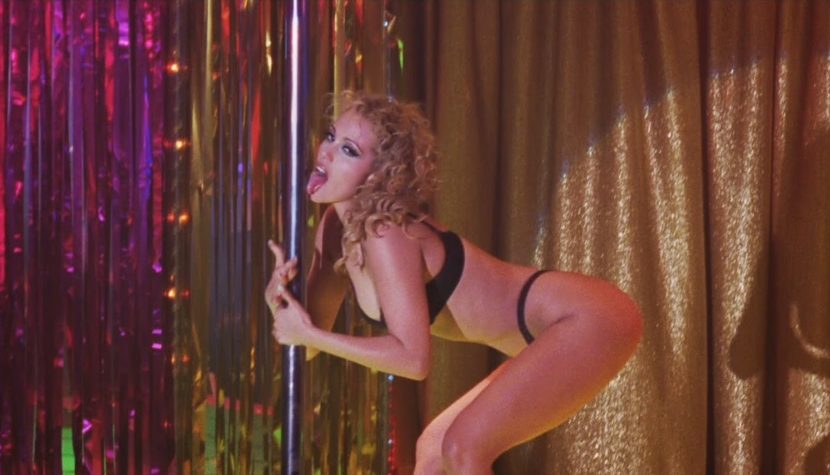

The concentration of kitsch and poor quality here is actually so high that it’s hard not to suspect premeditated action. The main character, Nomi (Elizabeth Berkley), resembles another feisty dancer written by Eszterhas – a girl from Flashdance, played by Jennifer Beals – but one on loads of amphetamine. It is a three-year-old child in the body of a tall, sensual woman. The only form of speech available to her is screaming, the three emotional states she knows are rage, euphoria and sulking: alternately, without ceasing, after the first minutes of the film, we feel exhausted from being in Nomi’s company. She gives a special show during hysterical fast food eating in one of the first scenes: first she tears a bag of ketchup and pours it over the fries with such aggression as if the fries were to blame for all her failures in life, and then, when asked by a new friend, where does she come from , she whimperingly exclaims “different places!”, throws her meal on the table, and collapses into the seat with a childish grimace. Emphasis, ecstasy, escalation: it was Verhoeven who ordered his actress to turn up all gestures, movements and behaviors, he pushed her towards creating one of the most confusing performances in American cinema – why?

If you stick to the interpretation of the whole as a social drama that didn’t work out – Nomi’s behavior becomes understandable towards the end of the film, when we learn about her dark past and dysfunctional family, which somehow explains her imbalance. However, if we look at the whole thing as a camp, then Berkley will become perfect in our eyes in its exaggeration, overkill, excess, in the category of “overstylization” it is an outstanding role. This second, camp interpretation of the actress’s handling makes more sense to me, because Nomi is not the only unnatural person in the world of Showgirls. No – the weirdness of Showgirls is precisely the fact that everyone here is equally artificial and ostentatious. Everyone is throwing themselves at each other and screaming in a veritable parody of human contact, two besties are jumping wildly on the couch because one of them got her nails done, and the spasms of pleasure experienced in the pool are more like electric shocks on the table of a sadistic psychiatrist.

The impression of watching this movie is that it could be made by an alien who knows human behavior only from theory: perfectly empty dialogues, exchanges, such as the following conversation between Nomi and Cristal, in which the latter compliments the bust of the former:

“You have nice tits. They are beautiful.

– Thanks.

– I love beautiful tits. I have always loved. And you?

“It’s nice to have nice tits.”

– Do you like them a lot?

– What do you mean?

“You know.”

“I like them in a nice dress, in a tight bra.

“You like to show them.”

It is hard to imagine that such an experienced screenwriter as Eszterhas would write such lines seriously. Unless, as commentators in the 1990s maintained, the writer’s low form was to blame for his wholesale intake of cocaine. Also, I don’t know if the lead choreographer, Marguerite Derricks, was influenced by more than Verhoeven when she was putting together the dance sets, asking her to choreograph at once sexual, wild, violent, and disturbing, but the end result is something so narcotically bizarre that it’s hard not to agree with commentators calling Showgirls the least sexy of sexy movies. It’s hard to blame the actresses for this state of affairs, since most of them (including Berkley) had dance experience, and their uncoordinated movements are choreographed.

Kitschy glitz?

Verhoeven’s energetic style leaves no space for the viewer to breathe. The story of Nomi is an amusement park and roller coaster, a wheel of fortune. In the first five minutes of the film, the protagonist manages to: hitch a ride to Vegas, threaten the driver with a knife and miraculously avoid an accident, win a lot of coins in a slot machine, lose a suitcase with all her belongings, let go, cry, attack a strange woman’s car with her fists, go with a strange woman for lunch and find her a roommate.

The director hinted here and there that the inspiration for the filming of Showgirls was the painting of George Grosz. Indeed, in Verhoeven’s portrait of Las Vegas one can see a resemblance to the grotesque ugliness and noisy Berlin of the 1920s from the paintings of the German artist. The capital of casinos and striptease in Showgirls is a sequin, neon monster, cannibalizing its own inhabitants, the antithesis of beauty, the apogee of vulgarity, the kingdom of artistic emptiness. Jost Vacano’s camera fetishizes the kitschy glitz of Vegas; Added to all this is Verhoeven’s characteristic mix of ugliness, physiology and sex, and the dark baroque so beloved by the director turns into bright rococo in an unprecedented way compared to the rest of his oeuvre.

So no, no, no – apart from whether it’s successful or not, Showgirls is a conscious stylization. The author’s stamp is also reflected too clearly in each frame. So if it is a pastiche, what is traversing? If camp, what kind of pedestal kitsch? If satire, then for what? And finally: if satire is so deeply hidden in the layer of the work and so not obvious, is it good satire? It so happens that I have my own answer to these questions and I will not hesitate to write it down below.

First of all: Verhoeven is an artist who willingly uses strong means of expression and the poetics of shock, but the irony in his works is much more subtle and difficult to grasp. The Dutchman’s films often make fun of something, but the satire never comes to the fore in them, it is rather a wink of the eye, it works on the principle of “who knows, knows”. Like Sharon Stone, who throughout Basic Instinct mocks Michael Douglas’ tender male ego, and he misses most of her allusions. In Verhoeven’s works, added meanings never interfere with the captivating story, do not slow down the action and do not dominate the effective audiovisual layer, thanks to which his films work on so many different layers … and the irony inscribed in them so often turns out to be too discreet for the viewers to pick up.

Second: Showgirls is a satire on the broadly understood Americanness created by a European, and as such – not easy to notice by Americans. They do not belong to nations as self-aware, complex and sensitive to even a trace of criticism directed at themselves, as, for example, Poles. No wonder then that Verhoeven’s giggle in the background of all Showgirls frames remained inaudible to Americans for so long.

But let’s start from the beginning. Showgirls begins with a young hitchhiker entering a huge American car, driven by a boy with an Elvis haircut, with country speakers playing, and going to Las Vegas, where the girl intends to start all over again and find wealth and fame. American dream to the power. However, everything that follows is a deconstruction and ridicule of the “from zero to hero” myth, which is done not through scathing derision, but through a slight but noticeable exaggeration of the clichés.

Cristal Connors, played with exaggerated nonchalance by Gina Gershon, is a comic book villain whose only motivation is to harm the main character. James (Glenn Plummer) and Molly (Gina Ravera) exist only to support and help the main character. In general: all the characters introduced into this world exist only in relation to the main character and for the main character, and everyone treats the main character as someone special from the first meeting, although from the viewer’s perspective, she does not stand out with beauty and talent compared to other dancers. The main character herself is a boss bitch driven to the absurd, with an eternal streaky face, a clichéd independent strong girl of American pop feminism, the protagonist of Hollywood, clumsily trying to reflect the female perspective, and still soaked with small gaze. And of course, according to the logic of Tinsletown, she succeeds in everything from the very beginning, despite stupid decisions and mistakes: she gets the job despite insulting the producer at the casting, performs in the main production after only one rehearsal, despite numerous mistakes during her stage debut, she becomes the main competition and eventually the team leader’s successor.

Pop culture references and American satire

Individual scenes are so breakneck in their message that they can be derived either from the clumsiness of the creators or from their satirical intentions; Verhoeven’s earlier work precludes option number one. My favorite of such narratively clumsy scenes is the sequence with one of the dancers throwing crystals at the feet of a rival couple. The images lead the viewer by the hand: slow motion enters, we have a close-up of Nomi’s face to make sure that she saw what happened, and ominous music emphasizes the wickedness of the act. Zero subtlety leaves the viewer no room for independent thinking – which is a feature of the play that the Dutch director has repeatedly described as hated, so it’s hard to believe that he uses pathology so extensively in Showgirls without hidden goals.

Verhoeven remains faithful to the conventions of genre cinema until the very end and after all the horrors experienced by Nomi, he serves her a clichéd ending with a happy ending, conversion to the right path, restoring justice and kicking (literally) the ass of the main baddie. Because the director does not reinterpret the clichés in any place, but only strengthens them in a camp fashion, the “uninitiated” viewer may have a problem with noticing the satirical nature and will classify the whole thing as simply a bad film

Verhoeven plays with pop culture, but does he convey some deeper critique of American society? Yes. First of all, I see Showgirls a mockery of America’s view of eroticism and sex; from this view, which vulgarizes and commercializes sexuality, uses it as an advertising ploy and manipulative trick, tries to force it into narrow frames and show only the aesthetic, generally accepted side; all the while pretending to be prudish and willing to censor those who don’t fit, and thus remains a parochial view, faithful to the Puritan roots from which the USA grew. Verhoeven goes all the way into this utilitarian, safe sex from American movies with his naturalism, physiological fixations and his view of eroticism as something inherently non-normative and not subject to standardization. That’s why his sex and striptease scenes are such an antithesis of the common understanding of sex appeal. So at the end of a hot lap dance, Nomi tells the man to put his hand in her panties to check if she has her period. That’s why the queen of the Cheetah club is the chubby Henrietta “Queen of Tits”, obese and adoring her body without embarrassment, joyfully and openly celebrating every element of human sexuality. That is why, finally, the bewildered audience mostly rated Showgirls as a film in poor taste.

Verhoeven also pushes hard for the ideals of a Western, extremely commercialized society. Nomi’s goal? Buy yourself a Versace dress (the only right pronunciation is verseys). The scene in front of the brand’s store brings kitsch to a boil. The pace of the film slows down, generic, moving music pours out, and Nomi’s eyes shine as she tells her friend about the dress she just saw, as if she was talking about the most important man or the highest fulfillment in life. The authorities of Western society? Artificially promoted celebrities, stars and starlets. The space show in Stardust, maintained in the atmosphere of space Barbarella, shows the elevation of individuals to the status of deities. The film ends with a raid on a billboard with the image of the main character and the inscription “Nomi Malone is a goddess” – an ironic punchline to the two-hour screening showing how Nomi reached this place by ungodly roads.

Conspiracy theories can be made that Paul Verhoeven wants to tell us some dark truth about Hollywood through Showgirls. The grotesquely brutal, pornographically unrealistic rape scene, taking place at the time of the industry event and thanks to the world-class star, is a literal show of the dirt hidden behind the scenes of show business. Hollywood’s dual nature is embodied by Zack Carey, the producer Nomi and Cristal compete for, sleeping with him to ensure their success. From the viewer’s perspective, however, Zack is just gross in his ill-matched clothes, bizarre vest, greasy bangs falling over his forehead and a perpetual goofy smile on his face: no charisma, no intelligence, no personality. This guy is a kind of Hollywood “expectation versus reality.” It is not without significance that he is played by Kyle MacLachlan, an actor who brings semantic baggage to every role: he is first and foremost Lynch’s man. Compared to his polished image from Twin Peaks in Showgirls, he looks at most like an early disco polo star, but just like Agent Cooper, he functions at the junction of two realities: the apparent, charming and delightful and the real, hidden and dark. And just like in Blue Velvet, she peeks under a beautiful, neat dummy of American society to expose the rot and stench underneath.

Lynch connection

Speaking of David Lynch, I have one little Showgirls conspiracy theory related to him: I believe the director was inspired by this movie when making Mulholland Drive (and a number of others, as we know). Let’s make a deal: we’ve sailed far from the author’s intention anyway and we’re quite cool in these dangerous waters, so let’s dive deeper into the depths of over-interpretation. The first time this thought came to my mind was when in one of the scenes Cristal said that she was from Del Rio, Texas. Who sings at Mulholland Drive? Rebekah Del Rio. Then the associations went down hill. Both films are about a young blonde who tries to make a career in the entertainment industry. In both, she meets a mature brunette who has already achieved what the main character aspires to. In both, they compete for the favor of one very influential man in the industry. A specific relationship develops between the two women: a bit of jealousy, a bit of admiration, and a bit of erotic fascination (in both films we also have an almost identical close-up of their kiss).

Further: both films play with the theme of the doppelgänger, split personality – the blonde and the brunette can be the same person, the former is the younger version, the latter the older version, devoid of illusions about the nature of show business. Both show the hideousness of this show business, and the main character makes a career through the bed. Finally, both films achieve the effect of hyper-realism, albeit with different means. Lynch would certainly have noticed that Showgirls is a perfect film simulacrum, a film valley of the uncanny, a creature only pretending to be reality, but through some internal crack, artificiality piercing every scene, being totally unreal and evoking a confusing sense of being in someone else’s dream.

Truly I tell you: Showgirls is a simulacrum, it is a movie simulation, a movie about a movie within a movie. In it, Verhoeven calls American pop culture a simulation of art, the same as the Vegas infrastructure shown in his film, which is a simulation of the Colosseum, an imitation of the pyramids and a cheap copy of everything sublime that humanity has created. The Dutch director, in his hail of American entertainment cinema as an amusement park, is not as gay as Martin Scorsese, because unlike the creator of Taxi Driver, he likes these mocked, trashy productions and knows how to play with them, creating in the process the craziest shit possible .

In his book It Doesn’t Suck, Adam Nayman calls Showgirls a “masterpiece of shit.” He also states that it is impossible to settle the argument about whether the film is a misunderstood masterpiece or the worst picture ever made. Showgirls is both of these things at the same time, and this is what makes it unique. Of all the attempts to capture the essence of this film, this one is my favorite.

Conspiracy theory

Also, for me, and this is another one of the numerous conspiracy theories fertilizing my imagination, Showgirls is a confirmation of the multiverse hypothesis. “It came from outer space,” like Rocky Horror Picture Show or Pink Flamingos, comes from an alternate timeline or some sick, broken thread of reality that never developed, where people jump on each other and yell and threaten each other with knives and taste each other’s monthly blood, and it all seems normal, and that’s how the cinema is made there. This flash of consciousness from an alien space-time, however, left a real mark of shame on the real biography. Not the director who came back into favor with later films. Not this producer who recouped financial losses with subsequent projects. I’m talking about the biography of Elizabeth Berkley, who showed everything as an actress and lost everything as an actress. Before her appearance in Showgirls, she was a promising teenage star of popular TV series – after her appearance in Showgirls, her agent abandoned her, no one wanted to work with her, and her name became synonymous with embarrassment.

All the most important works devoted to Showgirls, (let’s call them Redemption), were created relatively recently. Jefferey Conway’s book of poems Showgirls: The Movie in Sestinas is 2014, the aforementioned book by Adam Nayman as well, and the documentary You Don’t Nomi was shot in 2019. It is no coincidence that Showgirls is experiencing a renaissance of interest on the wave of debunking the Hollywood myth and the general crisis of the elite status of American cinema. What was just an undocumented suspicion at the time of the film’s release – that Hollywood is a place of systemic sexual violence – today, after #metoo, is a widely known fact. Viewers no longer buy into the Dream Factory myth. The viewership of the Oscar gala is declining from year to year, and the global monopoly on entertainment was long ago taken away from the Americans: for example, thanks to Asian productions such as Squid Game, much more original and more accurately reflecting social unrest than the nauseating ersatzs expelled by Hollywood. On the wave of these resentments, Showgirls emerged from the depths of oblivion.

Because Showgirls is a satire primarily on the mechanisms that set the wheels of Dream Factory in motion. It is a mockery of the fact that instead of despising producers and directors who despise their actors and actresses (like the star of Stardust, insulting the appearance of dancers and shouting at them: “Be nervous! Go ahead! Sell your body!”), we admire them, we explain a difficult character with a genius, and the more excesses an artist has, the more fascinated we are with him, as in some nasty version of the Stockholm syndrome (and like Nomi, who can take a lot from a mobbing director and adapt to the worst requirements of the business, “because that’s what’s needed here.”

There’s one brilliant scene in Showgirls that gives me chills. During an audition for a role in a play, a particularly obnoxious director complains about Nomi’s soft nipples and makes her put ice on them to make them stick out. The humiliated girl looks at him reproachfully, and after a moment she shifts her resentful, resentful gaze straight at the viewer, breaking the fourth wall. Her intense gaze locks on us for a moment, then there’s a montage cut and we see that she’s actually looking at Cristal looking at her. The director make a connection between a viewer and Cristal – sitting in the audience and, just like the viewer, eager for further effects, crossing borders in the name of the spectacle, without caring about the suffering of others. With typical overexpression, Nomi throws the ice bucket away and storms out of the room, shouting “I hate you!” into the ether. To whom are these words addressed? To the chubby casting director? To Cristal, who is having fun at her expense? To us, the viewers, for whom the fall of the girl is an interesting spectacle? To the entire entertainment industry that feeds on the sacrifice and humiliation of its performers? To Paul Verhoeven, who forces her to act out more bizarre scenes?

It’s hard to admit that our favorite director can be a dick. But alas, I have to: Paul Verhoen has been, and probably still is, a dick. He was when he convinced Sharon Stone that no one would see her naked in the cross-legged scene, and he was when he consciously made the unconscious Berkley into a caricature. The ostentatiously kitschy story of a young stripper is a self-referential satire on the entertainment industry and how people trying to succeed in it are objectified and degraded. The gloomy and unpleasant self-referential nature of the film, which transcends the fabric of the story, unfortunately also lies in the fact that by showing the pathology of Hollywood, he himself used and hurt his main star, devouring and spitting out her entire career. With this bloody conclusion I end my reflections on Showgirls.