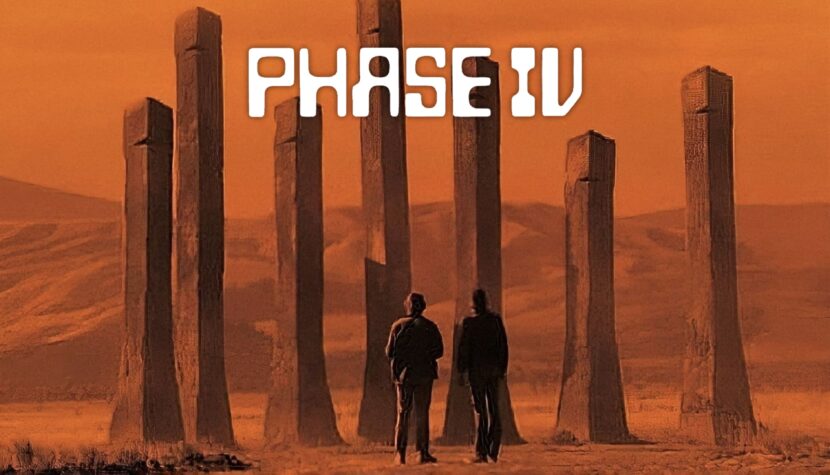

PHASE IV. Captivating and mysterious sci-fi horror

…, the opening credits, into an important and memorable structure. Graphic designer Saul Bass revolutionized cinematography by compelling filmmakers to pay significant attention to how a film opens, so that even before the plot unfolds, the audience would know or at least have a sense of what they are about to see.

Born in New York, Bass (1920–1996) elevated the opening credits, a secondary part of a film, into an art form. His methods were later adopted by many—drawing, photography, and moving frames served as perfect materials for building the mood and rhythm of a work, thematic introduction, and genre recognition. While they didn’t convey a story on their own, the credits always alluded to the narrative they were introducing. The fragmented titles in the opening credits of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho speak as much as Bernard Herrmann’s aggressive, string-heavy music. Similarly, the cutout hiding the text and the outline of a little girl at the beginning of Otto Preminger’s Bunny Lake Is Missing suggest not only the significant role of the child in the plot but also its uncertain status, reflecting in the narrative. Bass created the opening credits for over fifty films (his wife Elaine was the co-author of a considerable part of them), and towards the end of his career, he created credits for one of his biggest fans, Martin Scorsese. Bass’s contribution to the development of cinema is immeasurable, especially considering the present role and level of realization of opening credits in films. However, this creator once decided to test himself in something that forced him to shift his thinking to a more complex yet classical approach. As a director of a narrative work, he filmed Phase IV in 1974, a thriller on the border of science fiction and surreal horror. Despite his work on films as a visual consultant, storyboard artist, and documentarian (he won an Oscar in 1969 for the short film Why Man Creates), Phase IV remained his only narrative film.

The story of Phase IV follows two scientists, the older biologist Hubbs and the younger cryptologist Lesko, who venture into the desert areas of Arizona after increased ant activity is observed in that region. The cause of this activity (an unexplained cosmic event) seems as enigmatic as the subsequent developments—animals are killed by ants, a geometric sign appears in a nearby field as if trampled by someone (or something), and strange, tall sand towers near the research base put the characters on guard. While Hubbs tries to destroy the insects, convinced of their hostile intentions, Lesko decides to establish contact with them.

I suspect that a considerable number of viewers of Phase IV will react to the above description with a mocking smile—such a story may not encourage a thorough examination of Bass’s film, who chose a bold script for his debut. It is easy to fall into ridicule when talking about a duel between humans and ants, especially since the director strips his film of any humor, trying to present the actions of both sides with clinical precision. He doesn’t limit himself only to the human point of view, as in most stories that rely on the depiction of nature going wild (this horror subgenre is known as “nature runs amok,” although the term “animal attack” is also used), turning fauna or flora into an uninteresting antagonist. The actions of these creatures mainly amount to revenge on humans polluting the environment, and the overall ecological message, often accompanied by macabre imagery, prevails. Hitchcock’s The Birds (1964) lacks this didacticism, but George McCowan’s Frogs (1972), Irwin Allen’s The Swarm (1978), M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening (2008), and even Colin Eggleston’s role-reversed Long Weekend (1978) no longer shy away from it.

However, Bass in Phase IV treats the situation with a stone-cold face, surprising with its quasi-scientific approach and a narrative that allows us to follow the actions of both sides. The former is evident from the beginning of the film when we hear the voices of the characters off-screen explaining the importance of the discovery and the imminent danger if it is ignored. The text of a memorandum written by Hubbs (Nigel Davenport) refers to the observed unnatural behavior of ants. He believes that the previous antagonism between different ant species has been replaced by cooperation, which initially manifested as the elimination of their hostile counterparts. The biologist, fearing an escalation of these actions, sees no other solution than to immediately investigate the problem on-site and, as a last resort, launch a direct attack. Lesko (Michael Murphy), on the other hand, for a long time, doesn’t know what to make of the situation. He observes certain geometric regularities suggesting surprising intelligence in ants and the possibility of communication with them using the language of mathematics, while not being entirely convinced of the unequivocally hostile intentions of the insects.

Motives and relationships between the men don’t particularly interest Bass. He attentively follows their actions but doesn’t find intriguing characters in these roles, focusing more on their roles and duties regarding the common problem. The situation somewhat livens up when a young girl, Kendra (Lynne Frederick), joins them, miraculously escaping with her life not so much from the ants as from the spray that Hubbs used to exterminate the insects. However, Mayo Simon’s screenplay abandons this subplot. Conflicts between people disappear in the face of an unusual threat, especially since what the trio soon encounters transcends human understanding. Sand mounds built by ants are so perfectly aligned that sunlight effectively heats the walls of the research base; ants attack the integrated circuits of the computer, leading to serious damage; the insects’ response comes in the form of an enigmatic drawing. And as nonsensical as it may sound, Bass masterfully controls the entire narrative in an admirably effective way, preventing it from turning into a silly joke. The manner in which he presents his small heroes plays a significant role in this.

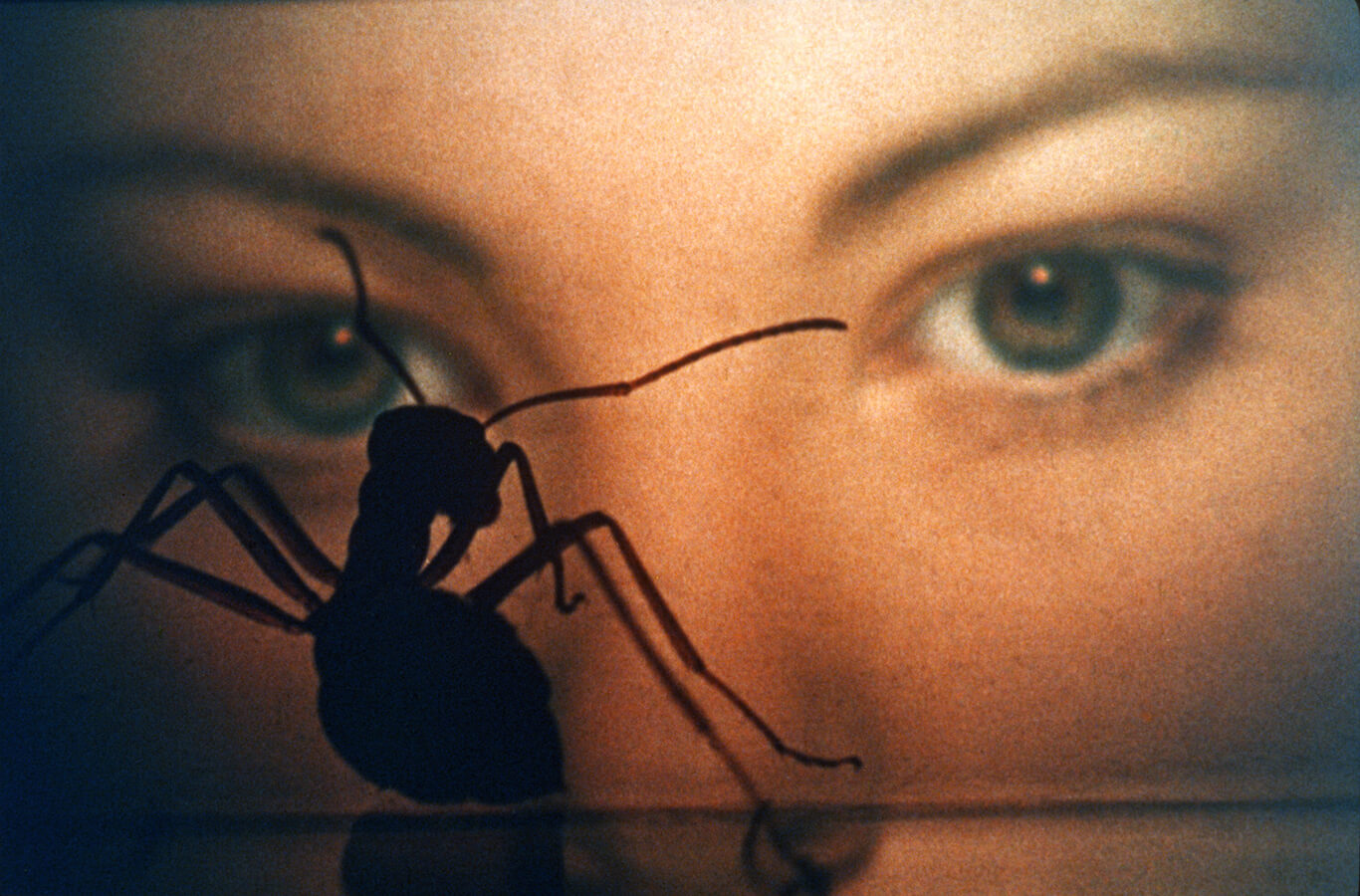

The ant scenes in Phase IV are masterful, not only due to their authenticity. There are entire sequences where all we get are images without any dialogue, explanation, or commentary, allowing the underground world to be watched like an alien, almost extraterrestrial civilization. Despite this, we have no trouble understanding the action scenes. In one of them, an ant takes a piece of poison, travels a certain distance, and then dies. Then another ant appears, takes the load, and also dies after some time. The situation continues, and the last insect reaches the queen, who, after consuming the poison, assimilates it, ensuring that future ants are resistant to it. Bass, in the “duel” scene of ants with a cricket, manages to outline the situation in a simple, unforced way, simultaneously building drama and introducing the viewer to a reality hitherto unknown.

Sometimes the director moves on the fringes of readability—observed events are left to our own interpretation, and sometimes they appear to be mere sketches, devoid of narrative value. They then resemble the opening credits he created. However, as fragments of a larger whole in a narrative film, they serve a slightly different purpose, creating a peculiar atmosphere and possibly depicting the beginning of a new hierarchy.

I won’t reveal what the fourth phase is, although on the other hand, official releases of Phase IV are missing a four-minute sequence from the ending explaining the title. It can be found on YouTube and will surely delight all fans of Luis Buñuel’s The Andalusian Dog—Bass’s surreal vision resembles a nightmarish dream, captivating and frightening with its psychedelic rhythm and frames of not entirely understandable content. At the same time, one can read from it a conclusion not only for the film’s characters but also for all of humanity. The horror of future events becomes palpable, regardless of whether the presented images are interpreted as a harbinger of positive or negative changes. Without this final fragment, Bass’s horror is somewhat devoid of deeper meaning flowing from previous events; the story ends before we learn what the director wanted to tell. He himself was dissatisfied with the interference of producers who cut these four minutes without his involvement. Without them, the film seems incomplete.

With Phase IV, Saul Bass proved that he could tell a story, even with some stumbles. His only narrative has a not very fast pace, sacrificing some interesting plotlines for images that are so fascinating and unprecedented that they become a topic in themselves. It is both a technical showcase, a brilliant setting for an absurd story, and a thoroughly original work, the suspension between symbolism and concreteness creating an unparalleled atmosphere and a strange denouement. The ants themselves may not be frightening, but the discovery of their intentions can leave one in awe.