OH, CANADA. Paul Schrader’s Reckoning Elegy [REVIEW]

Paul Schrader is a rare figure in American cinema today. A filmmaker and co-writer of films such as “Taxi Driver”, “American Gigolo”, and the recent “The Card Counter”, he has earned a reputation as a sharp and biting critic of postwar America, often exploring ethical and religious dilemmas that aren’t always straightforward (“The Last Temptation of Christ”, “Affliction”, “First Reformed”). Born just after World War II in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Schrader represents a dwindling generation, one steeped in the spirit of protest and shaped by the intersection of postwar conservatism and the defiant counterculture of self-styled nonconformists. Another representative of this generation was Russell Banks, who passed away in 2023. Banks, the author of “Affliction”, which Schrader adapted into a film in the ’90s, left behind a legacy that Schrader now revisits by adapting Banks’ second-to-last novel, “Foregone”, to the screen as “Oh, Canada”.

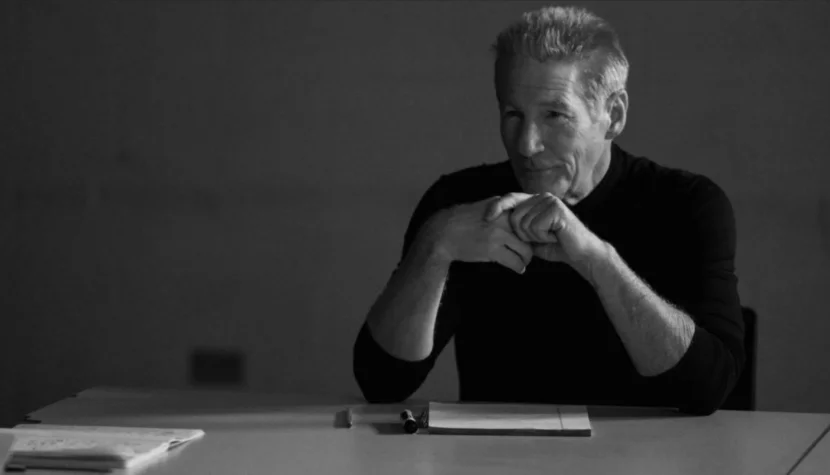

The film centers around an interview with Leonard Fife, a renowned documentarian, given in his Montreal home. Likely his last, as Fife is dying of cancer under the watchful care of his wife, Emma, and a private nurse, the interview serves as his farewell to the world and a final reckoning. Fife not only recounts his proudest moments but also reveals long-hidden sins and secrets that even his wife did not know. This intimate recording in a successful man’s home turns into a tension-filled scene between him, his loved ones, and the filmmakers eager to document his story.

Schrader weaves this narrative by playing with time, disrupting both the sequence and logic of events. Younger versions of characters meet their older selves, the older ones take trips into the past, and Fife’s storytelling is repeatedly interrupted and questioned as unreliable, seen as the delusions or even fabrications of a mind clouded by illness and medication. Schrader further emphasizes this non-linear memory work by mixing aesthetic techniques—color alternates with black-and-white footage, and various filters and aspect ratios evoke a ‘retro’ feel for specific scenes. The resulting kaleidoscope of scattered events unfolds as a complex, unconventional narrative, examining the life of an uncompromising visionary artist tormented by the looming specter of death.

Richard Gere plays the dying Leonard, returning to work with Schrader over four decades after “American Gigolo”. His portrayal in “Oh, Canada”, sometimes aggressive yet melancholic and filled with genuine emotion, stands out as one of his finest performances. Gere’s work is notable for blending the character from Banks’ novel with the author himself, who infused it with his own fears and regrets, as well as Schrader’s own reflections on mortality. Gere is supported by Uma Thurman, who plays Emma, Leonard’s wife, who is both supportive and burdened by the dark secrets that come to light during the interview. Unfortunately, Jacob Elordi, who portrays the younger version of Fife, fails to break away from his image as a handsome young man with a chiseled jawline and six-pack. His performance falls flat, coming across as an odd, less effective reprise of his role in “Euphoria“. This makes the flashback scenes feel disappointingly one-dimensional compared to the richly emotional contemporary sequences.

This issue affects “Oh, Canada” on a broader scale. Despite its thematic ambition, stylistic experiments, and meta-cinematic layers, Schrader’s film ultimately feels lackluster. The shifts between timelines lack fluidity, and the storytelling lacks the sharpness it needs. Gere strikes a more dramatic note, Thurman adds depth in her scenes, and the set design of the recording room offers some visual intrigue, but the screenplay’s reliance on convenient shortcuts and clichés holds back its potential. Schrader doesn’t succeed in infusing the story with the existential tension that usually drives his films. Even the title, which suggests a biting commentary on national or political identities, ends up feeling like a hollow slogan. Schrader’s usual style remains visually cold, but without the substance that his work typically demands.

This might be because Schrader focuses too much on the personal tone of “Oh, Canada”. In too many scenes, Gere’s character transforms into a defiant custodian of countercultural ideals, spouting nonconformist catchphrases and becoming a mouthpiece for a creator who seems to reflect on his past without fully admitting to his mistakes. It’s as if Schrader struggles with self-critique, even if only symbolically. Thus, he crafts an ambivalent narrative, torn between a genuine reflection on the ethos of the ego-driven artist-macho, who believes himself entitled to do more in the name of art, and a deathbed elegy celebrating that very ethos.