DIE NIBELUNGEN Explained: A Great Fantasy Spectacle

One of the most influential film theorists in history presented an extremely compelling thesis in the book. He observed a forewarning of nationalist madness in German cinema from 1913 to 1933, a madness that led to the outbreak of World War II. By placing characters from two different worlds in the title — the deranged psychiatrist from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and the leader of the NSDAP — Kracauer intertwined fiction and reality. In the expressionist madmen, who cleverly manipulate the protagonists of films from that era, Kracauer tried to see the specter of real tyrants. These manipulated characters were, in turn, a reflection of the German people, who, on one hand, dream of dominance, and on the other, easily submit to authority.

Kracauer’s text is a brilliant piece of literature. However, from a scholarly perspective, it raises many questions. It is hard to avoid the impression that the thesis proposed by the German researcher is somewhat exaggerated. The numerous examples and analyses do not prove certain assumptions but rather fit into a pre-established framework. Kracauer wrote From Caligari to Hitler in the United States. His emigration across the Atlantic was not voluntary; because of his Jewish roots, he had to flee Germany. During the war, on behalf of the Rockefeller Foundation, he analyzed Nazi propaganda films for the Americans. It seems, then, that the personal experiences of the scholar significantly influenced his work. Evil could not have come from nowhere, so Kracauer — due to his profession — tried to trace it somewhere between the frames of celluloid. Nibelungen

Why am I mentioning Kracauer at the beginning of a text about Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen? The reason is quite simple — due to the enormous popularity of From Caligari to Hitler, Fritz Lang’s films were viewed through the Kracauerian lens for many years. In his publication, Kracauer saw Die Nibelungen as a “manifestation of German nationalism” — a film that “through the objectification of characters in expressive decor, the creation of a ‘mass ornament,’ shows a totalitarian tendency and anticipates the mass stagings of the Nazi era, such as in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1934)”. Lotte H. Eisner, the author of another influential monograph on the expressionist movement, The Haunted Screen, also compared Nibelungen to the famous Nazi film. In the context of Lang’s film, she states: An individual is treated in Nibelungen as a static element devoid of individual life, frozen according to the plan of symmetry… The extras, gathered en masse, are also completely dehumanized. Did Lang indeed create a paean to Nazi ideology? Is this why Goebbels, despite knowing about the director’s Jewish roots, wanted to appoint him to lead the most powerful German film studio? I will try to answer these and several other questions in the following part of the text.

Chronicles Of The Weimar Republic

December 18, 1917, is one of the most important dates in the history of German cinema. On that day, by order of the commander-in-chief of the German armed forces, General Erich Ludendorff, the UFA film company was established. Germany quickly understood that cinema was an excellent propaganda tool. The newly formed company, uniting many previously existing production companies, aimed to create a positive image of Germany both domestically and internationally. The films produced by UFA were to counteract the intense anti-German campaigns of the Entente. One of the main shareholders of the company was Deutsche Bank. Thus, a true cinematic legend was born.

On November 11, 1918, in a railway car in the Compiègne Forest, Germany symbolically laid down its arms before the Entente countries. World War I ended, and the country along the Rhine faced enormous war reparations. The young Weimar Republic struggled with the post-war situation. The mood among the people was conflicted. On the streets, one could hear both communist and nationalist slogans. In 1923, with the participation of Ludendorff, the same man who had founded UFA, Adolf Hitler attempted a coup d’état (the Beer Hall Putsch). The state of the German currency did not help matters. In 1914, one U.S. dollar was worth about four German marks. By the end of 1923, twelve zeros had to be added to that four to obtain a dollar. Paradoxically, hyperinflation contributed to the success of UFA and its great directors, including Fritz Lang.

After the war, the government sold its shares in the company, which became a private corporation owned by powerful entities like Deutsche Bank and Krupp. Galloping inflation and non-revalued loans allowed UFA to make significant investments. The lack of revaluation meant that money invested in material goods (such as expanding film studios) was quickly recouped. For example, in October, UFA could buy equipment for 200,000 marks; by February, due to inflation, the same equipment would cost ten times more. However, without revaluation, the company would only have to pay back 200,000 marks. As a result, UFA quickly became a significant player. Its pride was the sound stage in the Staaken district of Berlin. During the war, the complex had served as a zeppelin hangar, but in the 1920s, it became the world’s largest film studio.

Similar mechanisms governed film production. In the early 1920s, there were no language barriers between world cinematographies, so UFA quickly began sending its films overseas. One advocate of this strategy was Erich Pommer, the producer of the famous The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. A leading UFA producer, Pommer advocated creating lavish films that matched Hollywood super-productions in scale but were artistically refined. This strategy guaranteed revenues in both the American and European markets (for example, in France, which craved artistic cinema and had no shortage of money after winning the war). Due to the poor state of the German mark, selling films on the foreign market and receiving payment in a stable currency was pure profit for UFA.

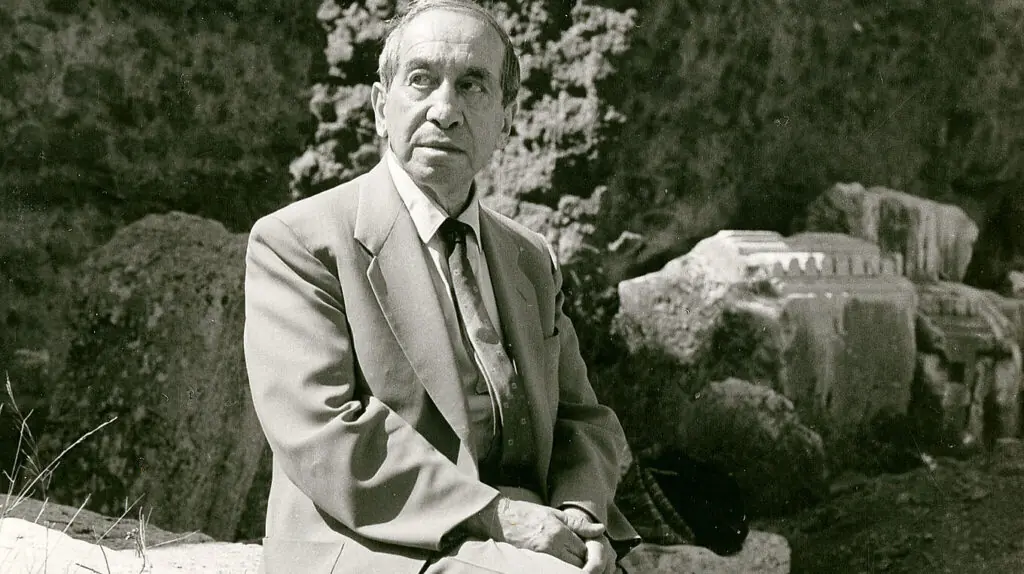

Husband And Wife

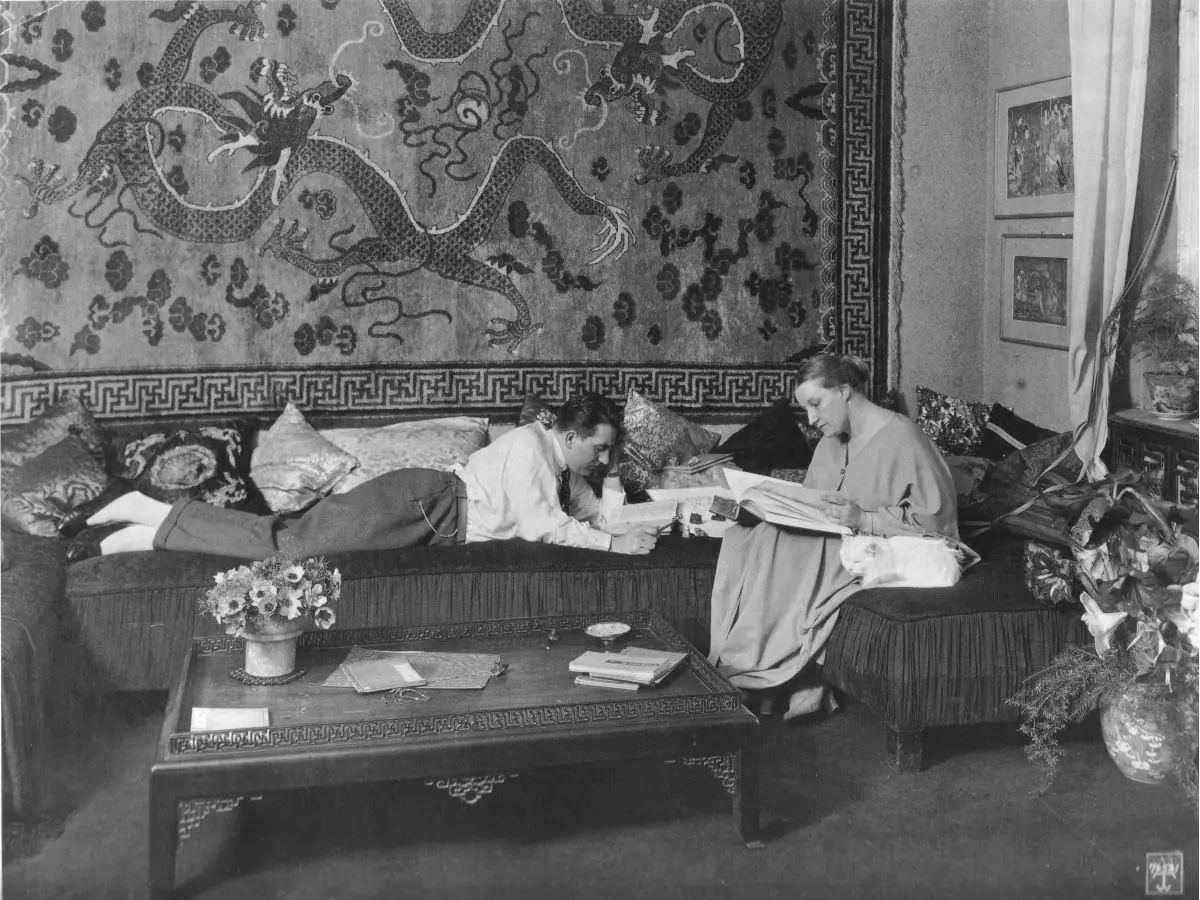

In 1920, Fritz Lang met Prussian aristocrat Thea von Harbou. Thea, the author of the novel The Indian Tomb, had just received a proposal to adapt the text for the screen. The film’s director was to be Joe May, one of the pioneers of German cinema. As fate would have it, Lang had been working on May’s productions since 1917 (mainly as a co-writer). It was no different for The Indian Tomb. The writer and the budding director quickly hit it off, united primarily by a fascination with the Orient. From the 1921 premiere of May’s film until 1933, all of Fritz Lang’s films were made thanks to script collaborations with von Harbou, who became the director’s wife in 1922 (following the death of his first partner).

Lang and von Harbou’s relationship was far from perfect. He did not shy away from the company of young women, who appeared behind his back as soon as he began achieving significant success. A few years after the wedding, Thea also had an affair (in 1933, Lang caught her in bed with a lover). However, the marriage was divided by another important issue. Fritz Lang had always been wary of Adolf Hitler’s brand of nationalism. When Goebbels offered him cooperation, the director decided to leave Germany immediately. Thea von Harbou did not share her husband’s view and clearly sympathized with the Nazi Party. The shadow of their ideological dispute can be seen in the films they collaborated on, including Nibelungen, which is an inseparable product of its time.

Germany, mired in crisis, needed grand narratives that would reinforce their sense of self-worth. The lost war and the reparations that affected the country’s honor could be depressing. The falling value of money and the growing assets of foreign companies only reinforced the belief among average citizens that it was time to wake up from the nightmare and take matters into their own hands. Soon, the word “nightmare” would acquire a completely new meaning. Nevertheless, before that, in February 1924, the first part of Nibelungen — The Death of Siegfried — premiered in German cinemas. Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou, and Erich Pommer brought the German national epic, a 12th-century story celebrating the strength of the Germanic spirit, to the screen. The film’s release coincided with the end of the inflationary boom that had driven UFA’s actions. At the beginning of 1924, the German government introduced a stable currency (the Reichsmark), which curtailed financial manipulations and brought the studio to the brink of bankruptcy. But that is another story — it’s time to give the stage to Nibelungen.

Siegfried and Kriemhild

It must be acknowledged that the Song of the Nibelungs possesses immense power and grandeur; it is difficult for a Frenchman to grasp this. It is a stony language; the verses are like rhyming blocks of stone. Here and there, in the cracks, bloody flowers bloom… It is hard for you, good, civilized, refined people, to understand the passion of the giants appearing in this epic… All the Gothic cathedrals have gathered on one plain… It is true that their gait is somewhat heavy, that some of them are so clumsy that their amorous ardor sometimes makes us laugh; but the jokes stop when we see them raging, lunging at each other… There is no loftier tower, no harder stone than the cruel Hagen and the vengeful Kriemhild.

Thus wrote the 19th-century German poet Heinrich Heine about the literary source of Lang’s film. Lotte H. Eisner applied his words to the cinematic version of Nibelungen. It must be admitted from the outset that Heine’s words perfectly capture what viewers experience while watching The Death of Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge. The first part of the film is a “gathering on one plain,” full of “amorous ardor that often makes us laugh.” The second part transforms into a “clash of Gothic cathedrals.” Sharp stones fall from their facades, crushing successive mortals. The cracks where “bloody flowers bloomed” are shattered, and the blood of the fallen floods UFA’s massive studio. There is no room for laughter or sentiment anymore.

The Death of Siegfried is a classic fantastical fairy tale. We meet the title character as he forges a sword, sweating profusely. A master craftsman examines the weapon. It turns out that the blade is so sharp that it can cut a bird’s feather as it floats down onto its edge. The master admits that he has nothing more to teach Siegfried and tells him to leave. Before setting off, the young man overhears a conversation about the kingdom of Burgundy, the castle of Worms, and the beautiful Kriemhild, who is waiting there for a valiant suitor. Siegfried decides to become part of this story. He asks his master for directions, and out of jealousy over Siegfried’s skills, the master directs him to a wrong path, leading him into a forest full of strange and dangerous creatures.

Siegfried unexpectedly takes advantage of this situation. As he makes his way through dense thickets, he encounters a dragon, kills the beast, and — following a lark’s advice — bathes in the blood of the dead creature. From then on, his body is impervious to all swords and spears. Only a small patch of skin near his shoulder blade remains vulnerable (during his blood bath, a falling leaf from a tree covered it). In the forest, Siegfried also meets the dwarf Alberich, who tries to kill the dragon-slayer. Siegfried avoids the dwarf’s tricks. After defeating him, Siegfried acquires the immense treasure of the Nibelungs, the mighty sword Balmung, and a cloak that allows him to become invisible and transform into another person. With this inventory, he heads to Worms Castle.

At the court, it turns out that King Gunther is in love with the warlike Icelandic queen, Brunhild. She has declared that she will only marry the man who can defeat her in a spear duel. However, Gunther is not a great warrior. On the advice of Hagen, the king’s most loyal supporter, Siegfried agrees to help Gunther (in exchange, he will gain Kriemhild’s hand). Using the magic cloak, he helps the king and defeats the Icelandic queen. After a series of unfortunate events and another magical intervention by Siegfried, Brunhild learns of the trick. In a fit of revenge, she accuses Siegfried, claiming that he — disguised as Gunther — deceitfully took her virginity. Furious, the king decides to get rid of Siegfried. He and Hagen conspire, leading to the fatal stabbing of Siegfried in the only vulnerable spot on his body. The hero dies, Brunhild commits suicide, and Kriemhild vows revenge on Hagen.

The second part of the film focuses almost entirely on her. Kriemhild falls into a murderous rage, resorting to any means to bring about her husband’s killers’ demise. Her path to vengeance involves marrying the king of the Huns, Etzel (a literary equivalent of Attila). While residing in his castle, she devises a plan. She asks her husband to invite Gunther and Hagen to celebrate the equinox. The men arrive with Burgundy’s troops. Kriemhild bribes the Huns to kill the guests. In the final scene of the story, Gunther loses his head, Hagen dies at Kriemhild’s hands and from the blade of one of the Huns. Her last wish is to be buried alongside Siegfried.

The Greatness of Nibelungen

The Nibelungen can amaze even modern audiences. Its scale can be compared without exaggeration to the largest super-productions of today. It is hard not to marvel at the fact that the film was shot in a studio. Towering castle turrets, streams, forests, jagged peaks, treasure-filled caves, royal chambers, and vast plains were the work of graphic designers and set designers — Walter Ruttmann, Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht. Lang’s film is undoubtedly one of the greatest achievements in set design in cinematic history.

Working in a studio allowed Lang to have complete control over the final look of the film. This is why nothing in Nibelungen happens by chance. Every composition is carefully planned. Many of them become visual commentaries on the stories of Siegfried and Kriemhild. When creating Nibelungen, Lang acts like a painter. The word is transformed into an image, but this does not mean it loses its communicative power. Nibelungen speaks to the audience continuously, throughout its five-hour runtime. When Hagen enters the chamber in The Death of Siegfried, we immediately know he is evil, strong, and dangerous. Lang dresses him in black, elongates his figure through costume design, and emphasizes his sharp features with a helmet. In full armor, he indeed looks like a Gothic cathedral detached from its foundations, spreading terror among insignificant humans. Siegfried appears only in light costumes; the camera often focuses on his smile and cheerful eyes. Despite his boyish naivety, he earns the viewer’s trust. His character often appears against idyllic natural landscapes — these pastoral scenes will witness both his romantic encounters and his death.

Lang does not only create static images. His camera perfectly captures the essence of the story being told. The Death of Siegfried is much more static, with a clear division into separate micro-stories — the journey through the dragon forest, the duel with Alberich, the first visit to the castle, the clash with Brunhild, and so on. Lang often lets us catch our breath and enjoy the frames, which grow darker and darker (a brilliant use of lighting). Kriemhild’s Revenge abandons the calm of the first part; it is violent and sometimes jerky. Lang’s camera reflects the emotional state of the protagonist and pulls the viewer into the mad whirl of plots and crimes leading to Hagen’s death. The idyllic landscapes of The Death of Siegfried are nowhere to be found, nor is the magical world of the Nibelungs, dragons, and enchanted artifacts. They are replaced by faceless Burgundian troops and hordes of Huns, who, at first glance, do not resemble rational human beings. Human passion kills fantasy.

A few lines above, I compared Lang to a painter; Jerzy Płażewski, however, calls Nibelungen “animated architecture.” While I have minor reservations about this comparison for the first part, Kriemhild’s Revenge indeed looks as if it were carved in stone. This is not a comparison meant to discredit Lang’s achievements. Properly crafted stone can look monumental and impressive.

Nazism

Over the years, largely under Kracauer’s influence, Nibelungen has often been seen as a covert endorsement of Nazi ideology. Supporters of this theory had various interpretations. Siegfried became a symbol of Germany defeated in World War I, Kriemhild a metaphor for the necessity to fight for honor, and Hagen the embodiment of the country’s enemies. However, the most serious accusations involved the use of extras and the film’s structure.

Compositions made up of dozens of characters that resembled moving mosaics rather than human beings, and the frequent subordination of characters to a strict frame composition, were said to foreshadow the dehumanization of humanity, the denial of individual value. Lang’s film was compared to the achievements of Nazi crowd architects like Leni Riefenstahl. The film’s subject matter certainly lent itself to such interpretations. After all, Nibelungen was based on the German national epic, which — despite its cruelty — glorified Germanic power and morality. However, we should consider whether the mere choice of source material and the decision to create a cinematic monument can be seen as promoting National Socialist ideas.

The answer, as is often the case, cannot be straightforward. One must remember the situation the German people were in when the decision to make Nibelungen was made. People crushed by the lost war, galloping inflation, pervasive poverty, and the unjust enrichment of a few potentates needed solace. Cinema was an escape from everyday problems. Tickets were inexpensive, and people were willing to spend their worthless currency on this type of entertainment. Referring to tradition and reinforcing cultural roots was necessary at that time — Nibelungen simply had to be made. The fact that Nazi propaganda later exploited the national myth for its own purposes is not the director’s fault.

It is also difficult to agree with the accusation of total dehumanization of the characters. Indeed, Nibelungen often feels like a fresco in which an individual is merely a component of a carefully thought-out composition. However, one must not forget that the pace, camera movements, and the creation of frame space are inherently linked to the emotional states of the characters and their relationships. Although Lang’s films may initially seem austere, devoid of human sensitivity (especially Kriemhild’s Revenge), a thorough study reveals that at the heart of the story lies the individual, with their personal dramas, dreams, weaknesses, and passions, which are the domain of humans, not Gothic cathedrals.

The most disturbing aspect of the film is the portrayal of the Huns, who, compared to the Germanic warriors, look like beings of a lower order. Etzel’s troops are depicted as a threat, a band of foreigners lacking moral backbone. Unfortunately, this reflects the sentiments emerging in post-war German society, where the Other was automatically considered an enemy. The shadow of von Harbou’s political views or a medieval stereotype of the “barbarian”? It’s hard to say.

Summary

Overall, Nibelungen is an absolutely outstanding film, masterful in terms of filmmaking craft and world-building. It is also clear that it is the predecessor of today’s great fantasy spectacles. The Death of Siegfried is almost classic sword and sorcery fantasy, while Kriemhild’s Revenge is its violent and poignant conclusion. Every fan of the genre should set aside a few hours for Fritz Lang. After all, it was in Nibelungen that man first faced a fire-breathing dragon, before only running away from dinosaurs.