LOGAN’S RUN. No-nonsense and still fresh science fiction

However, the result of this journey was always the same. The brilliance of the ideal world blinded only for a moment. After some time, a significant snag, contradicting everything around, would come to light, leading to the sad but obvious truth – the perfect system is just an illusion.

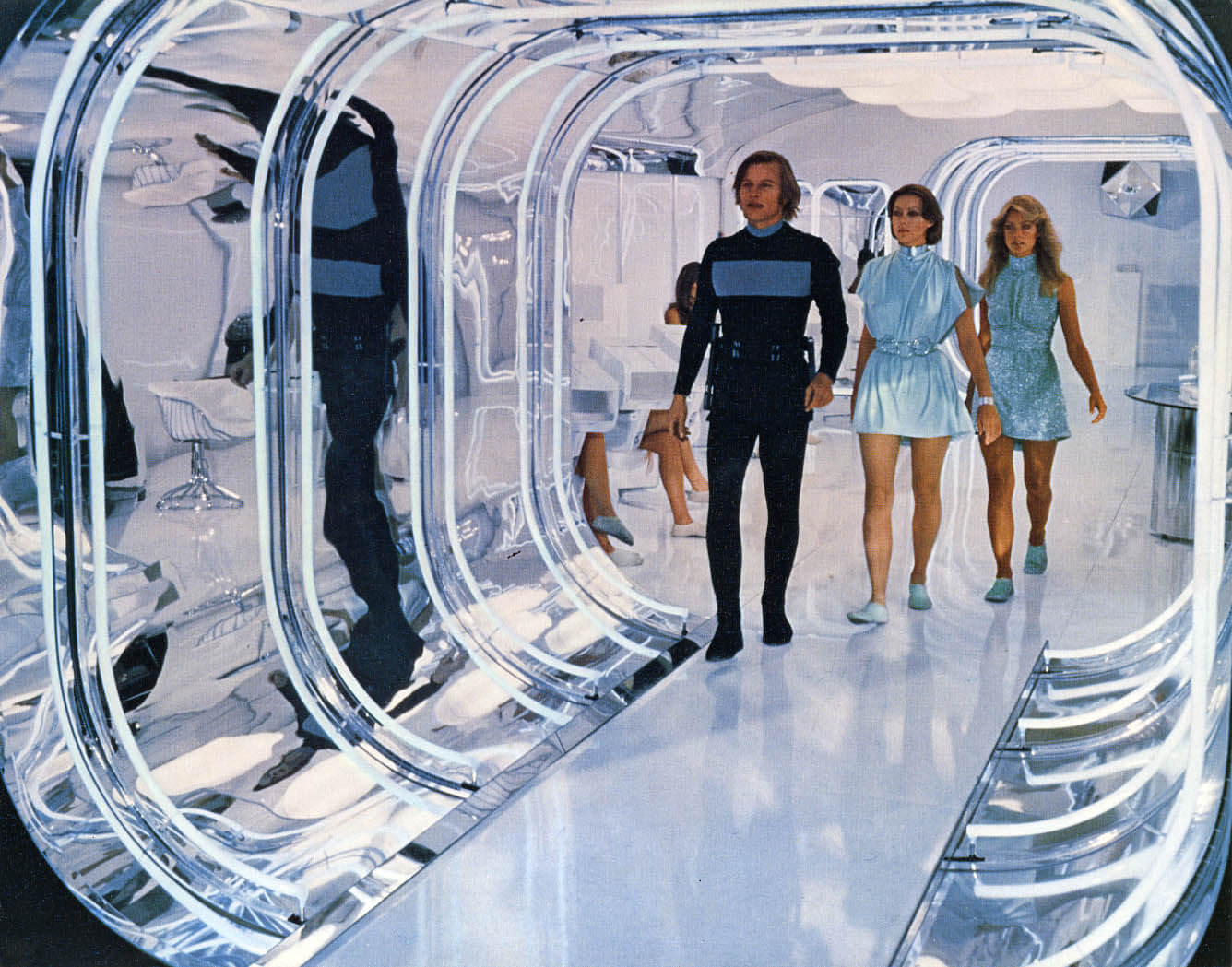

In 1978, Michael Anderson invited us on such a journey with his film Logan’s Run. Although the film is a result of combining familiar anti-utopian science fiction schemes, which solidifies its clichéd nature, over the years, it managed to develop its own personality. The audience liked it, as evidenced by the box office numbers (a budget of 9 million dollars returned almost three times in profits). As is often the case with science fiction works, Logan’s Run was most appreciated for its formal aspect – it even earned an Oscar for special visual effects.

In subsequent years, a television series based on Anderson’s film even made its way to the screen. Lately, there have been constant murmurs about a remake of Logan’s Run (at one point, Nicolas Winding Refn and Ryan Gosling were attached to a new version, but nothing came of it – although a remake under a different director is listed on IMDb as a project in development). There are, therefore, at least several reasons to acquaint oneself with Anderson’s vision – the creator, let’s add, enjoying a reputation as a solid craftsman in Hollywood.

The script is based on the novel of the same title by the duo William F. Nolan / George Clayton Johnson. But considering the plot, the association with Arthur C. Clarke’s The City and the Stars and the film Planet of the Apes works much better – classics of sociological SF. Logan’s Run is an exceptionally clever combination of anti-utopian tradition with post-apocalyptic fantasy, depicting a world struck by catastrophe. What does Logan’s Run tell us?

We find ourselves in the early 23rd century. The population, decimated by wars, resides in a closed city under a dome. Order in this world is maintained by artificial intelligence, a computer that rules over everything, including reproduction. Spoiled by the lack of the need to work, society worships the cult of hedonism, so pleasures have no end. In this perfect world, there is, however, one significant hitch. To maintain the status quo of the city, citizens who reach the age of thirty must undergo the (seemingly religious) ritual of the Carousel, leading to the process of so-called renewal, ultimately a euphemistic version of bidding farewell to life.

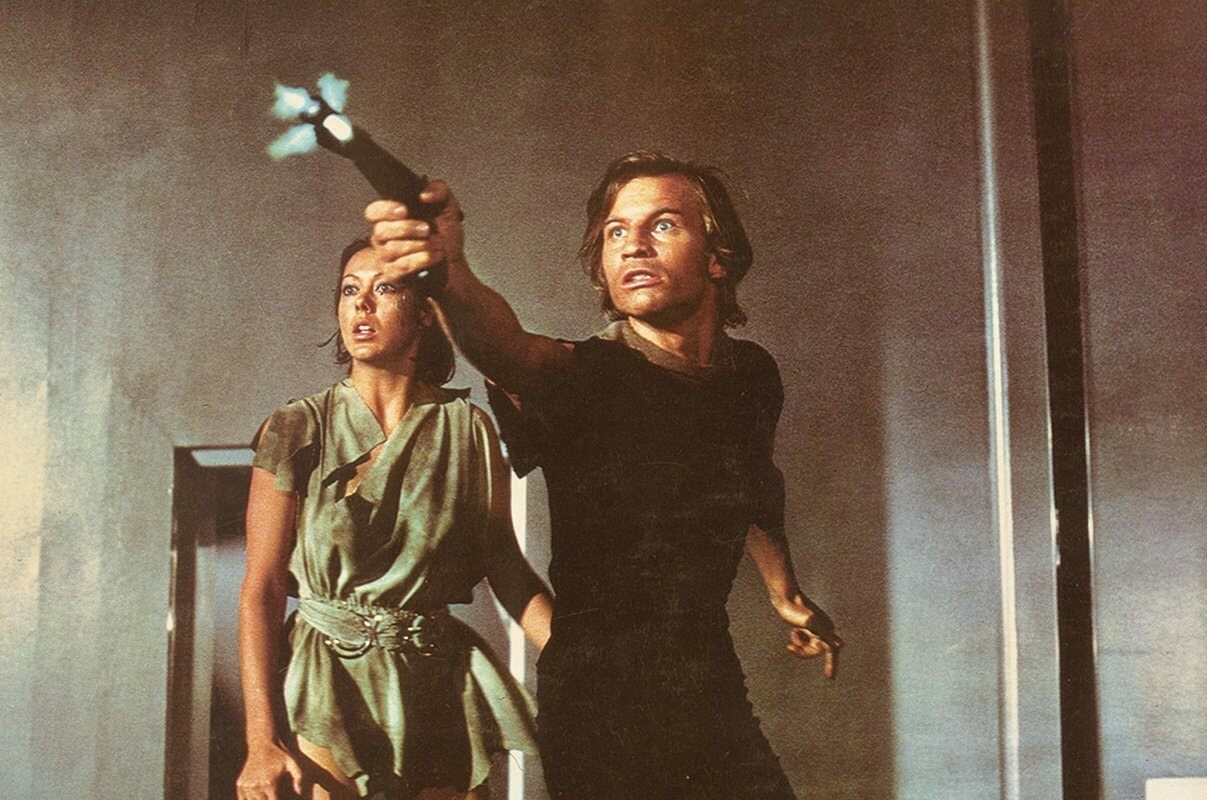

Like the later Rick Deckard from Blade Runner, the film’s Logan (Michael York) belongs to a special police force tasked with pursuing those who rebel against the system, dreaming of the mythical Sanctuary. A red light illuminating a citizen’s hand signals that the time for death has come, making room for others. If for some reason this individual wants to avoid their fate, Logan and his colleagues must find the rebel and eliminate them in a way far from glamorous. The game begins, however, when Logan himself receives the signal of his demise.

The book from 1967, serving as the literary basis for the film, was created as a commentary for the awakening counter-culture of young society at the time. Add that it was to be a highly critical commentary. The film also relates to the condition of the youth of that period in its content (the lifespan limit, however, was changed from the book’s 21 to 30 due to the actors’ ages). A civilization based on mindless, aimless existence, devoid of ideological order, based on pleasures of bodily indulgence and narcotic trips, has no right to exist. Paradoxically, therefore, it is not artificial intelligence that kills this society, but the gradually progressing decadence within it.

One of the most crucial moments in the film is Logan’s encounter with an old man hiding in the ruins of former Washington. The responsibility for wars rests on the shoulders of people of his generation. However, it is precisely he, the old man who remembers the past, who can provide the heroes with answers to their most pressing questions and give meaning to their actions. This is an important message. The experience and knowledge acquired by seniors are an invaluable resource for building a culture of a given society. Closing the door to using this resource may be due to extreme ignorance or the desire to influence young society.

I am aware that in the case of Logan’s Run, it would be appropriate to devote a few more lines to its production kitsch. In many moments, be it in the logic of events or in acting behaviors, you can see that Anderson’s film is very close to B-movie cinema. However, I appreciate Logan’s Run for its visual scope (including some interesting technical experiments) that harmonizes well with the not foolish content, conducted in a dynamic, adventurous convention. However, I am looking forward to a remake that could give this story more realism.