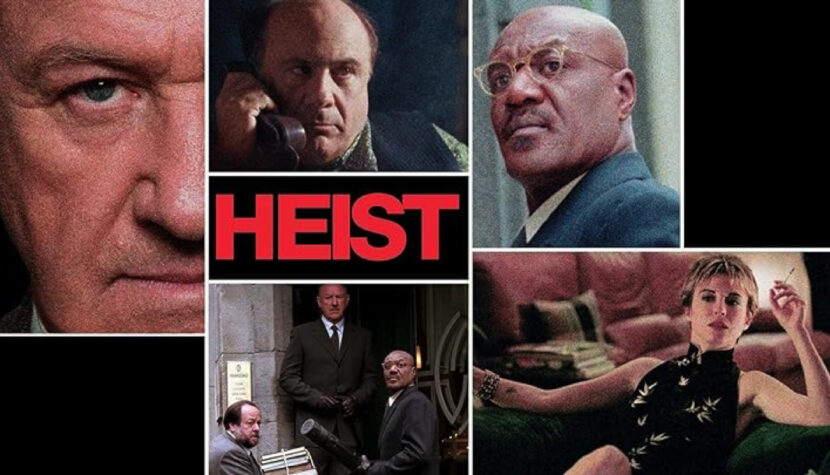

HEIST. David Mamet’s sophisticated intellectual thriller

… Malcolm X, Glengarry Glen Ross, and Wag the Dog. Who are we talking about? Of course, David Mamet. The pretext is his work Heist.

David Mamet, the director of Heist, is primarily known for his excellent thrillers House of Games and The Spanish Prisoner, is an independent creator, a writer of sophisticated plots, and an intellectual provocateur who smuggles unconventional content under the guise of a suspenseful drama—reflections on the human condition. He exposes weaknesses but also hidden desires and often overlooked needs that haunt characters, peering beneath the mask of pretense that surrounds us. In short, he is an excellent psychologist uncovering our impulses and motivations. As a master architect of cinematic intrigue and suspense, he perfectly fits into the tradition established by Hitchcock and Polanski. Today, when talking about famous cinematic surprises, people remember mainly Shyamalan, Fincher, or possibly Bryan Singer with his famous The Usual Suspects.

However, people tend to forget about the finely crafted films of Mamet, led by the mentioned House of Games, culminating in one of the best, most dramatic endings in the history of cinema. I had been eagerly awaiting his this film for months. It’s not surprising—Mamet, decisively focusing on intellectual entertainment and character drama rather than spectacle, is not among directors bringing in massive profits for producers and distributors. Unfortunately, I was disappointed. The director, returning after a certain hiatus to the style of film noir, disappoints with this work. Similar to the for example Femme Fatale by Brian De Palma, he created a film not much different from the average Hollywood production. In short, there’s nothing to boast about.

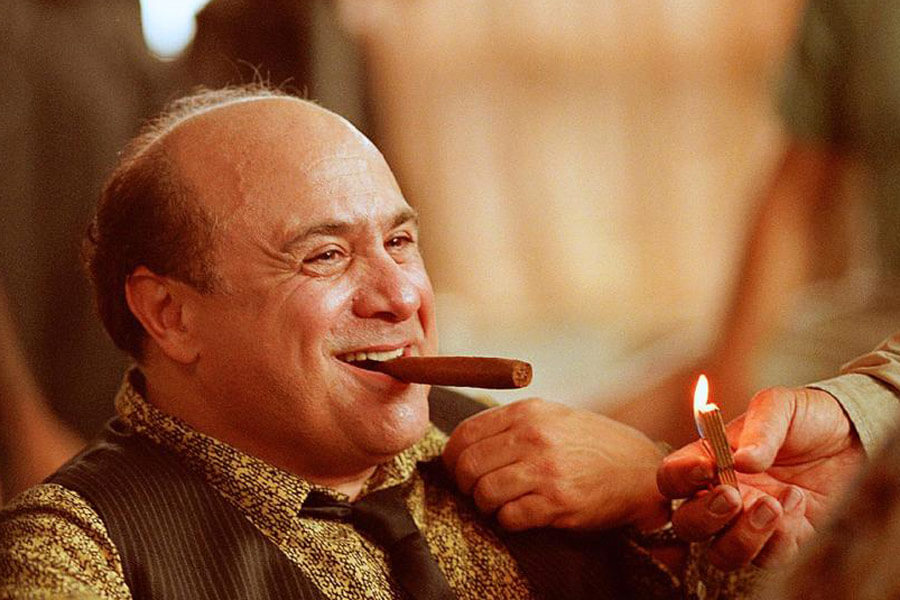

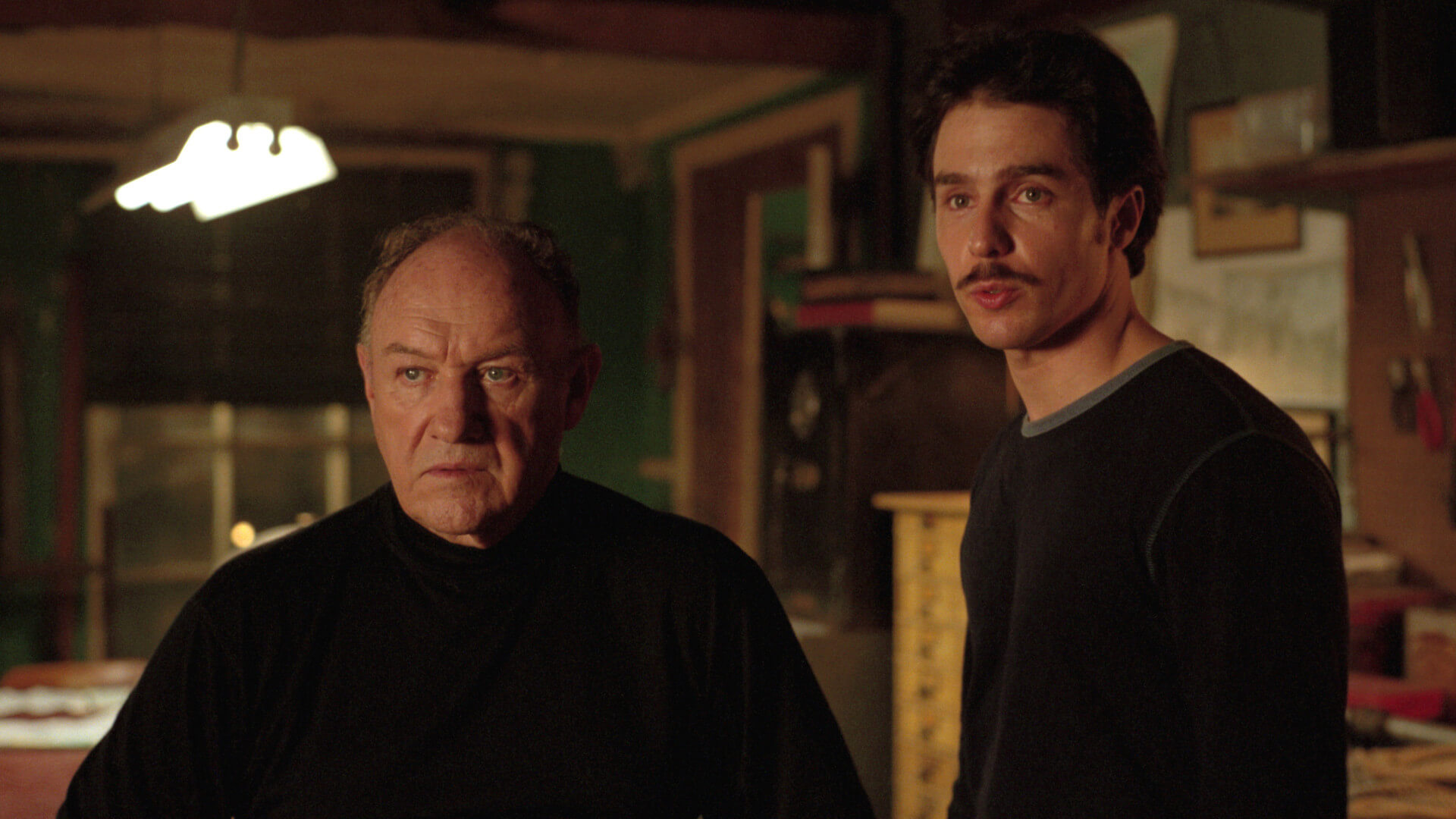

Joe Moore (Gene Hackman) is a thief; not just any thief, but the best in the business. He doesn’t work alone; for years, he has been accompanied by a well-coordinated team of specialists: Bobby Blane (Delroy Lindo), Pinky (Ricky Jay), and his wife Fran (Rebecca Pidgeon). The entire operation is run by the resourceful and cynical Bergman (Danny DeVito), who finds suitable targets and finances the entire enterprise. Unfortunately, during the last job, Joe is caught on security camera at the crime scene. This becomes the direct reason for his withdrawal from the business. However, Bergman has other plans for him. Blackmailing Moore with the threat of not paying his share of the loot, he tries to force him into organizing a heist on a Swiss gold transport. Joe, compelled by the situation, decides to discourage Bergman.

Mamet’s films are known for their complex, intricate plots that even more sophisticated viewers may find challenging to follow. The same is true in this case. The director doesn’t spare us mental gymnastics and doesn’t allow us to look away from the screen, as it would risk losing the thread of the film’s sophisticated plot. In Mamet’s previous works, this technique, often used, left the viewer exhausted but satisfied with the intellectual play the creator provided. In the case of Heist, it only leads to exhaustion. There are twists, exciting moments, surprises, but at some point, I felt that the multiplication of plot twists serves only to impress the viewer and not to tell an interesting story. Each element, if isolated, could serve as a model for any creator drawing on the proud traditions of film noir.

In Heist we have a vividly portrayed protagonist in Gene Hackman, a true femme fatale (Rebecca Pidgeon), themes of loyalty and friendship, and, of course, the reason for all the commotion—the gold transport. However, the problem arises when it comes to combining these perfectly prepared components into a coherent whole. In short, it leads to boredom: the intellectual play stops engaging the viewer when they can no longer distinguish who deceived whom, when, and how. The comedic, somewhat satirical character of the main antagonist, Bergman (brilliantly played by Danny DeVito), also doesn’t fit well with the rather serious tone of Heist. It creates a visible (perhaps intentional) boundary between the serious world of thieves—professionals and the grotesque, somewhat unreal world of gangsters—clients. When conflict arises between them, it’s clear that there will be casualties at some point. However, when they do occur, they feel as unreal as the perpetrators of the crime—simply not very credible.

The final trial also leaves a certain dissatisfaction, and the appearances created by Mamet for the sake of surprise make us wait until everyone rises and laughs at the perfect joke that the unfortunate viewer fell for. All of this poorly serves the coherence of the film. Finally, I saved a particular stumble (emphasized by other reviewers) for the end, something that shouldn’t have happened in Mamet’s usually impeccable scripts. I’m referring to the previously mentioned video recording plot, which exposes Joe Moore and becomes the reason for his departure from the profession. Mamet breaks the old Chekhov’s rule that says if a gun is hanging on the wall in the first act, it must inevitably be fired in one of the following acts. The video recording remains silent as if under a spell and has no intention of firing. This subplot becomes the driving force for the main character, serving as a pretext for the development of the plot, but it lacks a spectacular conclusion that could contribute to the additional dramatization of the events.

David Mamet is a director, erudite, a connoisseur of the human psyche, and an excellent dramatist. Heist fits perfectly into his previous directorial achievements with one “but” however. This time, despite—or perhaps because of—the refined construction, the film’s form surpasses its content, which is the direct reason why it unfortunately does not equal his outstanding genre predecessors—House of Games and The Spanish Prisoner. This does not change anything in David Mamet’s position as one of the outstanding creators—intellectuals; it remains intact. However, it disappoints those who expect another cinematic gem from the demystifier and connoisseur of the dark corners of the human soul, including myself.