GREMLINS. Funny, parodic, pastiche but definitely horror

… or the action-packed Die Hard. Is it because Gremlins directed by Joe Dante is a worse film or one that has aged? Not necessarily. It’s more about what the director achieved with this family-friendly horror that determines its current status – after all, who wants to be scared during the holidays by a film supposedly aimed at the entire family, especially the youngest viewers? They are likely to be terrified by the sight of grotesque and crazy creatures that – initially fluffy and cute-looking – actually have dark souls and anarchic tendencies. The Gremlins not only cause mischief but also destroy, harm, and kill. They do it with a smile on their faces, laughing wildly and unrestrained; we also laugh at what we see on the screen, which doesn’t change the fact that the titular beasts, which used to scare us when we were children, continue to be frightening today.

Gremlins, debut screenplay by Chris Columbus (future director of Home Alone and the first two parts of the Harry Potter series) begins with a scene that introduces us to the film’s main theme, which is how America assimilates everything foreign, somewhat at their own request, to turn it into a product, without worrying about the consequences of changing the identity of that thing. The kind but unlucky inventor, Rand Peltzer (Hoyt Axton), is dragged by a Chinese teenager to his grandfather’s antique shop to buy something, anything. Rand is not interested in antiques until he stumbles upon a Mogwai, a little creature locked in a cage that hums a pleasing melody. The American wants to offer $100 for the mascot, then $200, but the shop owner, an elderly man, explains that the Mogwai is not for sale. However, his grandson, aware of his grandfather’s financial problems, secretly sells the creature to Peltzer, explaining the rules he must follow in taking care of the furry little creature. Of course, each of the three rules will be broken, indirectly due to Rand himself, who later gives Gizmo, as he will name the purchased Mogwai, to his son as a Christmas present.

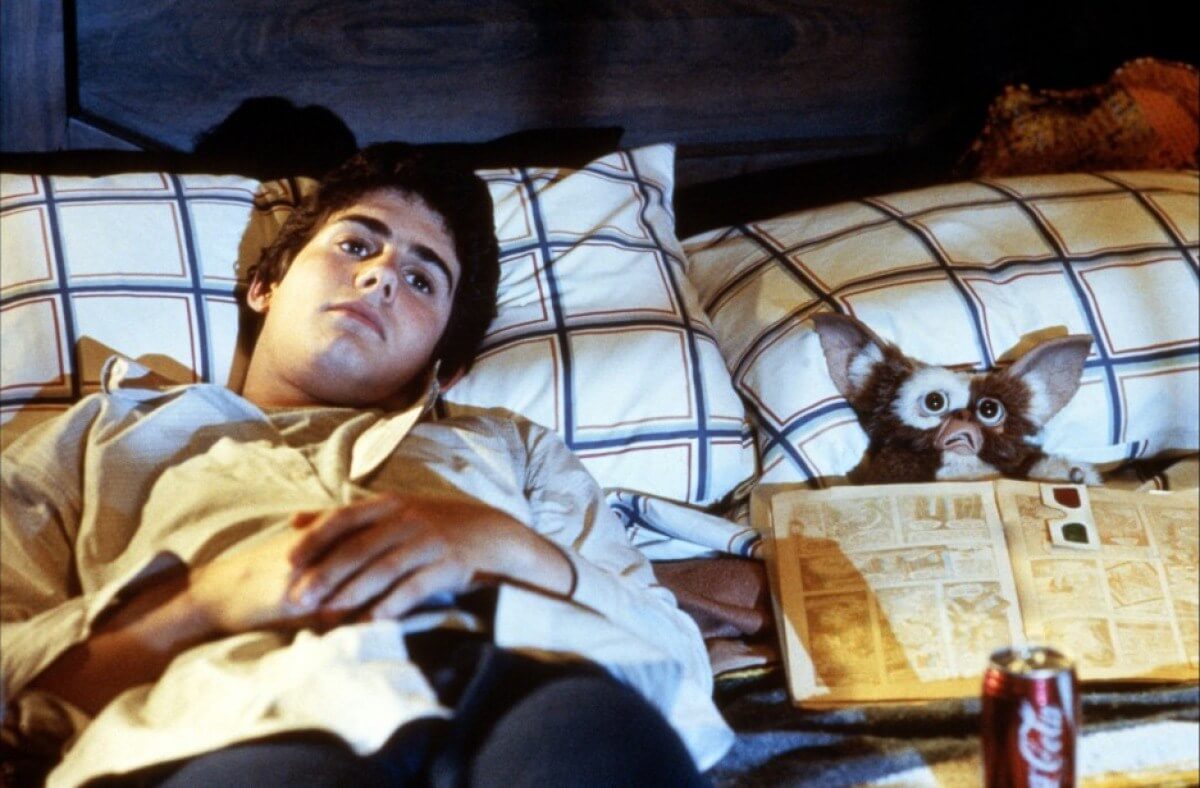

We like Rand, and we also like his son, Billy (Zach Galligan), because they are likable and good people. But they are also foolish, believing they can control something they do not understand. Elder Peltzer buys Gizmo (which can also be translated as “gadget” – it’s hard to find a better example of how Rand treats Mogwai) as a gift for his firstborn, but when the creature multiplies after getting wet, breaking one of the rules, Rand sees an opportunity to profit – now not only he but anyone can have a sweet furry creature in their home. However, Gizmo’s offspring is not as cute as he is. The grimaces on their faces suggest sinister intentions, and on the first night, they tie the Peltzer’s dog with Christmas lights so that he hangs himself on the porch. Later, Billy is tricked by them to break another rule – not to feed Mogwai after midnight – thus turning the small furballs into large, green, and hideous monsters. From that moment on, Dante’s film becomes a full-fledged horror, which, on the one hand, is realized in the monster movie genre, and on the other hand, complements it with a satirical vision of revenge by a foreign culture, which, once completely Americanized, loses what was true in it.

The term “gremlin” itself dates back to the time before World War II when any malfunctions and failures in RAF aircraft were blamed on little creatures. Later, there was Roald Dahl’s children’s book The Gremlins (1943) and an episode of The Twilight Zone (1963) in which a nervous airplane passenger, played by William Shatner, sees a strange figure on the wing of the plane. Echoes of the creatures’ aviation heritage are heard in the film itself in a conversation with Mr. Futterman (played by Dante’s regular actor, Dick Miller), a war veteran who believes that gremlins are primarily a foreign plague lurking in non-American vehicles and electronics. But ultimately, the creatures, while indeed originating from a foreign culture, resemble unruly children of Western pop culture – they love watching TV, go crazy in the cinema, throwing popcorn and loudly singing along with the song from Snow White on the screen, they love unhealthy food, and disdain fruit. In a bar scene, one of them pretends to be an exhibitionist, while another imitates a rapper adorned in gold. Gizmo is sweet, innocent, and unique, while his “brothers” seem to be a manifestation of the worst aspects of a consumerist and violent civilization.

Kingston Falls is ostensibly the ideal American town, but – ironically – even without the gremlins, the world it portrays is infected with evil, albeit in a more classic form. The wealthiest person in town, Mrs. Deagle, resembles a cross between Ebenezer Scrooge and the Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz – she seeks to evict people from the buildings she owns and threatens the main character with the horrific fate of his dog. Kate (Phoebe Cates), Billy’s love interest, tells him one of the most depressing Christmas stories ever heard in cinema, as evidence that Christmas is not a time of love and joy for everyone. The well-intentioned Mr. Futterman’s comments are tinged with xenophobia. What I like about Gremlins is the cleansing power of the mischievous creatures’ actions, as they punish the entire community of Kingston Falls for its apparent sugar-coating and perfection. It affects both the good and the bad because this is the only way the lesson will be remembered, and perhaps the same mistakes will not be repeated (those who have seen Gremlins 2 know that this is not the case).

Dante had previously made a name for himself as a skillful director of horror films with works like Piranha and The Howling. In the case of Gremlins, he doesn’t shy away from his dark sensibilities, infusing the film with imagery of an exceptionally sinister aura. The cocoons from which the adult versions of the mogwais hatch are appropriately slimy and unpleasant, clearly suggesting that even the future creatures won’t be cute. During the pool scene where the main gremlin, Stripe, falls into the water, it seems to be boiling – the green light, heavy steam, and underwater flashes can still frighten even the youngest viewers today because there’s something unnatural and simply evil about it. The sight of hundreds of gremlins emerging from the darkness on a bright winter night is also impressive, although the animation in this scene stands out from the rest of the film. The attacks of the creatures also contain a lot of black humor, given the mischievous nature of the titular characters, but even then, Dante doesn’t shy away from underlying tension and surprising brutality. In one of the film’s best moments, Mrs. Peltzer spectacularly kills three gremlins, but the fourth, hidden in the Christmas tree, almost kills her, jumping at her and strangling her with a cable.

Gremlins is a horror film. Period. Dante’s film is funny, somewhat parodic, definitely pastiche, and Jerry Goldsmith’s music perfectly combines sweet, somewhat naive melodiousness with the mischievous nature of the titular characters. But above all, it is scary. I knew it when I first saw the film at the age of 7 or 8, and I know it now. Americans knew it too during the summer of 1984 when it was released. It was Gremlins and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, released in the same season, that led to the creation of a new age category – PG13. The audience’s reactions, especially the children’s, were so intense that the co-creator of both films, Steven Spielberg, appealed to the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) to introduce stricter guidelines for images that are not suitable for the youngest viewers. Up to that point, there was nothing between the PG (films for children, with recommended adult supervision) and R (films for older audiences, requiring adult accompaniment if someone is under 17). As it turned out, the heart-ripping scenes in Indiana Jones and the creatures exploding in the microwave in Gremlins were definitely too much for toddlers.

Six years later, a sequel was made, also directed by Dante, which moved the action from the small town to the metropolis. The sequel is surprising because it’s much crazier, more playful, and satirical, aiming even more squarely at consumerism, but it’s practically devoid of the horror found in the original.