FREAKS Explained: Sadly Misunderstood Fairy Tale

On the screen, characters like Frankenstein, the Mummy, and Dracula reigned supreme, cementing themselves in the history of modern culture. The director of the latter – Tod Browning – was thus given free rein to create another terrifying monster. However, he chose a slightly different approach, showcasing not one but an entire group of them, and in an unusually sympathetic and unconventional light. Thus, in 1932, a true bastard child of contemporary celluloid was born – a creation for which no one was prepared, Freaks.

Freaks is often categorized as a horror film, but this label is both inaccurate and deeply unfair. Certainly, the appearance of some titular characters might evoke unease or churn the viewer’s stomach, and the finale depicts them as almost bloodthirsty beings, driven by a razor-sharp desire for revenge. However, the film contains far more humor (sometimes dark), grotesque elements, and even hints of crime drama, with the entire work being, at its core, a pure drama. A drama not just about the titular characters – wronged either by evolution or by fate, which deformed them, leaving the circus or freak shows as their only refuge – but also about their constant internal suffering. Frequently mocked, pointed at, or even feared by more delicate onlookers, they endure perpetual anguish (even as they consciously earn a living from their appearance).

Paradoxically, the central drama does not revolve around the so-called “ugliest” or most “grotesque” freaks of nature, but around a single representative. Hans, a dwarf who looks like a little boy, naively falls in love with a trapeze artist named Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova – one of the few “normal” and professional actors in the film; interestingly, Myrna Loy was originally cast for the role). Unfortunately, the love is unrequited. The shallow Cleopatra and her lover, a circus strongman, regard Hans as a walking joke, exploiting him to access his rumored fortune. Blinded by love, Hans ignores the danger and the affections of Frieda, the one who truly loves him and is his equal.

This is the entire plot, further enriched by glimpses into the lives of other “freaks” and their roles within the circus hierarchy. The story is neither particularly complex nor sophisticated. Nor is it especially expansive, given that the runtime is just over an hour. To add to this, the presentation of the plot is underwhelming. The dialogue is clunky, reminiscent of 1980s soap operas (though it does feature a few gems), and the production has aged significantly over 90 years since its release. Over time, the film itself has become something of a “freak,” and it’s hardly surprising that, from today’s perspective, it’s considered an old movie, unlikely to frighten more than a few – if any. Indeed, this is the 21st century, an era of promoting all sorts of minorities, deviations, and broadly understood otherness. One might even imagine that Freaks would fare much better today, though still far from perfectly. So why all the fuss?

Undeniably, human curiosity hasn’t changed. Nor has a certain masochistic tendency to find entertainment in things (and not only things) that defy norms – in so-called exotica or, naturally, macabre elements. Freaks satisfies this voyeurism in spades, showcasing on the big screen sights that remain difficult to comprehend even today. A man without arms or legs who functions independently; a half-woman, half-man; the aforementioned dwarfs; obligatory conjoined twins; or people with various head or limb deformities. It’s all here! In an age of superheroes shooting lasers from their eyes and running through forests wielding blades, this might be a tough pill to swallow – but these are real mutants. No special effects, no computer enhancements, no superpowers. Pure nature in its cruelest, most fascinating form.

And since, regardless of personal views on such matters, it’s genuinely hard to look away from some of these sights, it’s no surprise that audiences reacted primarily with shock upon the film’s release (one woman even sued the filmmakers, claiming the screening caused her to miscarry). For many, this film was like stepping into an entirely different world – one they hadn’t known existed. These were like “freak shows” of yore, as popularized by P.T. Barnum – whose musical biopic The Greatest Showman starring Hugh Jackman we saw not long ago. This is a fitting comparison, as Browning drew inspiration from his early years spent in the circus as a clown and acrobat (some cast members also worked in the circus). Another source of inspiration was Clarence Aaron Robbins’ short story Spurs, initially acquired for Hollywood by Lon Chaney, and ultimately forming the basis of Freaks.

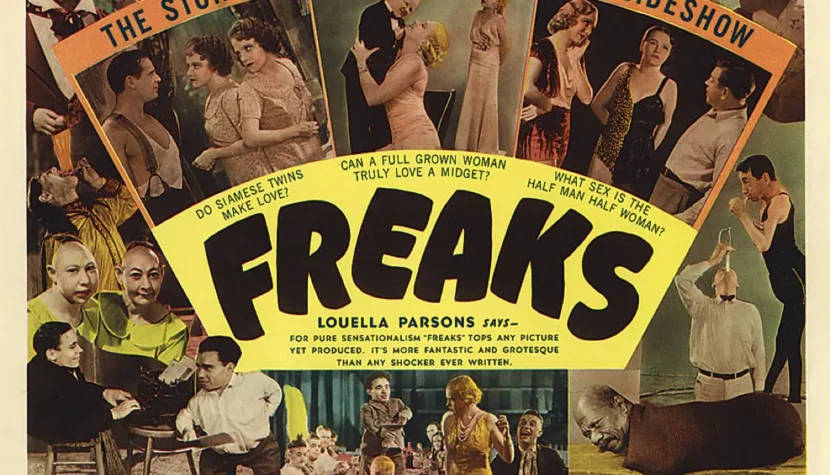

MGM Studios shot the film entirely on its own lot, keeping the main cast hidden not only from the outside world but also from the “full-fledged” members of the crew, who never shared meals or bathrooms with the “freaks.” The finished film was advertised with slogans worthy of cheap, traveling carnival shows, like: “The strangest, most shocking human story ever told! Are you afraid to believe what your eyes see?” This was enough to draw audiences to the premiere screenings in droves.

Ultimately, the budget of $350,000 didn’t even come close to breaking even, as Browning’s work was immediately decried as disgraceful and blasphemous after its initial screenings. Audiences fainted, critics lambasted the creators, and local authorities began banning the film, where it remains prohibited in some areas even today. The situation wasn’t much better across the ocean – in the UK, the film wasn’t officially released until 30 years later, and even then, only with the highest possible age restriction: X. Caught unprepared for such a backlash – or for what Browning had delivered in the first place – the producers heavily censored their own work (the infamous Hays Code did not yet apply to them).

Nearly 30 minutes of various scenes were cut, never to be recovered, despite many efforts to locate them. The film was reduced to just 64 minutes, which is painfully evident, as many scenes end abruptly with no cause-and-effect continuity, and some subplots are left hanging. Attempts were made to change the bittersweet ending in various ways, but to no avail. Reduced to the role of the tragic (yet vibrant) characters it portrayed, the film was not only quickly pulled from cinemas but also largely disowned, sold to the first buyer for a modest sum.

This celluloid outcast – too grotesque, offensive, and simply too ugly for mainstream audiences – was relegated to the underground, eventually gaining cult status during late-night marathons popular in the 1960s and 70s. Remarkably, its infamous reputation inspired two remakes: the B- or even Z-grade She Freak in 1967, and Freakshow fifty years later by the notorious Asylum studio. Both were outright disasters – in form and content – entirely missing not only the spirit but also the essence of the original.

Regardless of one’s opinions on Browning’s magnum opus, it aspires to much more than simply shocking audiences with people without limbs or mocking their appearances to boost others’ self-esteem. It’s a parable reminiscent of the timeless and still relevant fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. This is evident from the prologue, where Hans’ story of unrequited love is recounted by a third party – partly as an introduction to a freak show, but also as a moral lesson. A similar approach, with comparable effect, was used in an episode of Black Mirror.

It’s a great pity that Browning’s vision wasn’t understood – particularly since Freaks, though black-and-white, constantly oscillates in the gray area of moral ambiguity among all its characters. Sadly, the film’s impact was utterly destroyed, and its essence lost amid cuts, poor advertising, and a wave of collective panic reminiscent of Orson Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds broadcast. Unlike Welles, however, the uproar around Freaks didn’t benefit its creator. Browning shared the fate of his deformed creations, who literally killed his career. Forced into early retirement, he spent the rest of his life in seclusion, becoming an outcast himself. Unlike his film, he was completely forgotten – and that is the truly terrifying freak show.