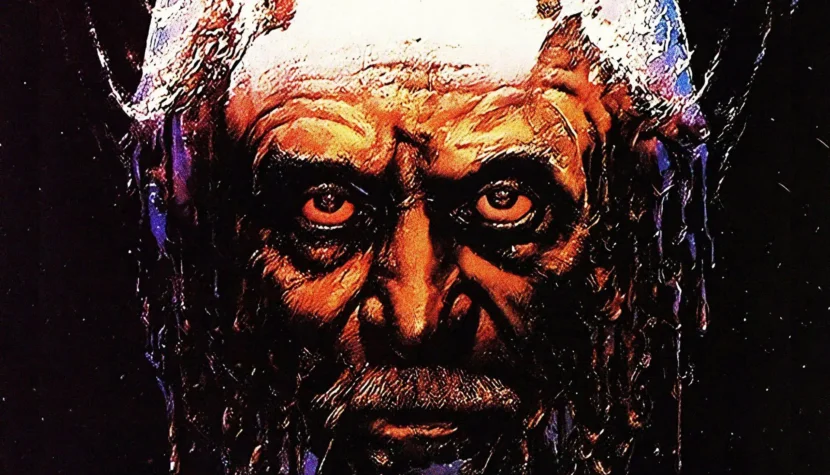

DEAD MAN’S LETTERS. Is the end of humanity science fiction?

“Dead Man’s Letters” by Konstantin Lopushansky is a manifesto film, anti-war and pacifist. It’s ideologically intriguing, especially because it was made in the USSR, a state with militaristic, expansionist, and politically vampiric tendencies. The production years (1986) likely play a role here, as the communist system in the Soviet Union was already severely degraded. Chernenko died in 1985, followed by Gorbachev, who had to radically clean up the USSR, regardless of party lines. Who, then, would bother with some niche cinema when it was urgently necessary to save mining, housing, and other important sectors of the economy? “Dead Man’s Letters” survived and can serve today as a metaphor for what will happen to our beautiful human civilization if we fail to respond in time to the budding totalitarian regimes, with which you don’t negotiate but suppress before they reach their lethal maturity. “Dead Man’s Letters” is more post-apocalyptic cinema than strictly science fiction, as its reflection on nuclear war is more philosophical than scientific. But does that really matter in the overarching perspective the film presents?

It’s certain that fans of sci-fi, especially older ones, will find the film thought-provoking for a long time. They need not worry that “Dead Man’s Letters” is a Soviet production. In this case, the execution is neither childish, nor will any screws fall out during the course of viewing. The film is well-made, with bold outdoor scenes where the post-nuclear war landscape is depicted very suggestively. Sometimes it’s a pity that most of the production is kept in sepia tones, with a few scenes in cyanotype (those foreshadowing hope), yet there isn’t a single color scene. I don’t mean the entire film, but the introduction of some motif in full color, not necessarily in the external world, would have given the production even more character. The core of the plot is the dramatic story of a professor, a Nobel laureate, who, along with a small group of museum workers, sits in a bunker. From the context, it appears that the museum was converted into a shelter, or the shelter was already part of its security system. In any case, people took refuge there from the consequences of a global nuclear conflict that erupted between nations unnamed in the story. The important thing is that the world was completely destroyed, something the professor doubts as he writes letters to his missing son. Larsen also doesn’t believe in his son’s death.

Hope keeps him alive, and the few excursions outside somehow still reinforce it, although the images he sees (the children’s ward), the orders the doctor tells him about, the situation with restrictions, and the shooting of people— even in such a devastated world—should make him realize that his son couldn’t have survived. Yet, what parent would believe that, especially as the professor soon finds himself alone—his sick wife dies, and the rest of the bunker inhabitants decide to move to another supposedly safer place for so-called “conservation.” Everyone except one person, who commits suicide. “Conservation” in the film means being sealed underground for up to 50 years. The authorities thus assumed that nothing remained on the planet’s surface, and the only way for the remnants of humanity to survive was through complete isolation.

The professor doesn’t accept such a disconnection from the world. He has his hypotheses, perhaps driven by irrational hope, but he was already a scientist, and nothing good came of it for the world. He tries to remain a father until his death, because it’s a much more important role than conducting experiments, the results of which led not to the development of civilization, but to its painful end. “Dead Man’s Letters” is a sad film, often very theatrical, existentially philosophical, dark, and offering no hope. In terms of science fiction, viewers won’t find scientific explanations of how to survive in the face of a nuclear apocalypse, although the vision of the world destroyed by it is coherent. Even the dog wears a gas mask. Attention was paid to scenographic details, and the people really behave and look like remnants of a barely-surviving rat pack, nervously scavenging for scraps of food and ready to kill each other for meat at any moment.

The remaining question is how much of this vision of the end of humanity is today’s science fiction—in the colloquial sense of something unlikely to happen. It seems that even the harshest regimes wouldn’t voluntarily resort to such radical methods, as they too rely on their own survival. It would be different if only they possessed total weapons. Then, the desire for domination through the destruction of the enemy could prevail, but fortunately, that’s not the case. There is a balance of power, similar to that during the Cold War. The problem will undoubtedly arise when an additional factor enters the game, one that is non-human, rational, and conscious to boot. Somehow, our human history is unfolding into an evolutionary whole. Species in nature become extinct for various reasons, including being replaced by a more dominant one. Surely, however, many desperate letters to our loved ones will remain after us, both analog and digitally stored, in which we desperately seek justification that our time on Earth was more needed by it than by ourselves.