DARKMAN. Superhero monster transcending the genre

Darkman may not be the first title that comes to mind when talking about the most famous comic book adaptations, if only because it isn’t one. In the late 1980s, director Sam Raimi wanted to make Batman or The Shadow, but when it turned out that the rights to both had already been sold, he decided to create his own superhero. This is how the titular masked avenger was born, whose ability was to transform into any person. An impressive advertising campaign with the slogan “Who is Darkman?” helped the film become a hit, even though the studio didn’t believe in its success, and Raimi lost his heart to it with each successive re-editing of the film. However, it’s hard to imagine the director’s further career without this title.

So who is Darkman? He is Peyton Westlake, a brilliant scientist working on inventing synthetic skin. He’s a good man who loves his girlfriend, Julie. However, her work unexpectedly turns their idyllic life into a nightmare. One night, intruders led by gangster Robert Durant break into Westlake’s laboratory in search of a document belonging to a woman that incriminates a prominent businessman. The intruders kill the scientist’s assistant, severely mutilate him, and then blow up the entire place. Miraculously surviving but horribly disfigured, Westlake ends up in the hospital, where doctors subject him to an experimental surgery that makes him unable to feel physical pain but at the cost of emotional and psychological turmoil. Soon, dressed in an old trench coat and hat, with his face wrapped in bandages, Westlake decides to seek revenge on his tormentors and win back his lost love, using his invention in the process.

The screenplay is based on the classic theme of revenge, which turns an ordinary person into a vigilante. However, Raimi is more interested in the monstrosity of the main character than heroism. One might think that Darkman is not much different from Batman or the Punisher, except that unlike them, Westlake’s dark side is also expressed in his appearance. His physical deformity, especially his face, can repel many—thanks to Tony Gardner’s brilliant makeup work, we clearly see the charred areas on his head, the paleness of the untouched tissue, and the absence of lips exposing his teeth. However, it’s the change in character that is the most interesting aspect here, an eternal mood swing that turns a broken man into a maniac, a romantic into a madman. Raimi already played with this motif in his debut Evil Dead – Ash’s possessed friends (and later even Ash himself) were demonic beings one moment and then returned to their human form and behavior the next – but in Darkman, it takes center stage, infusing the familiar comic book theme with horror elements.

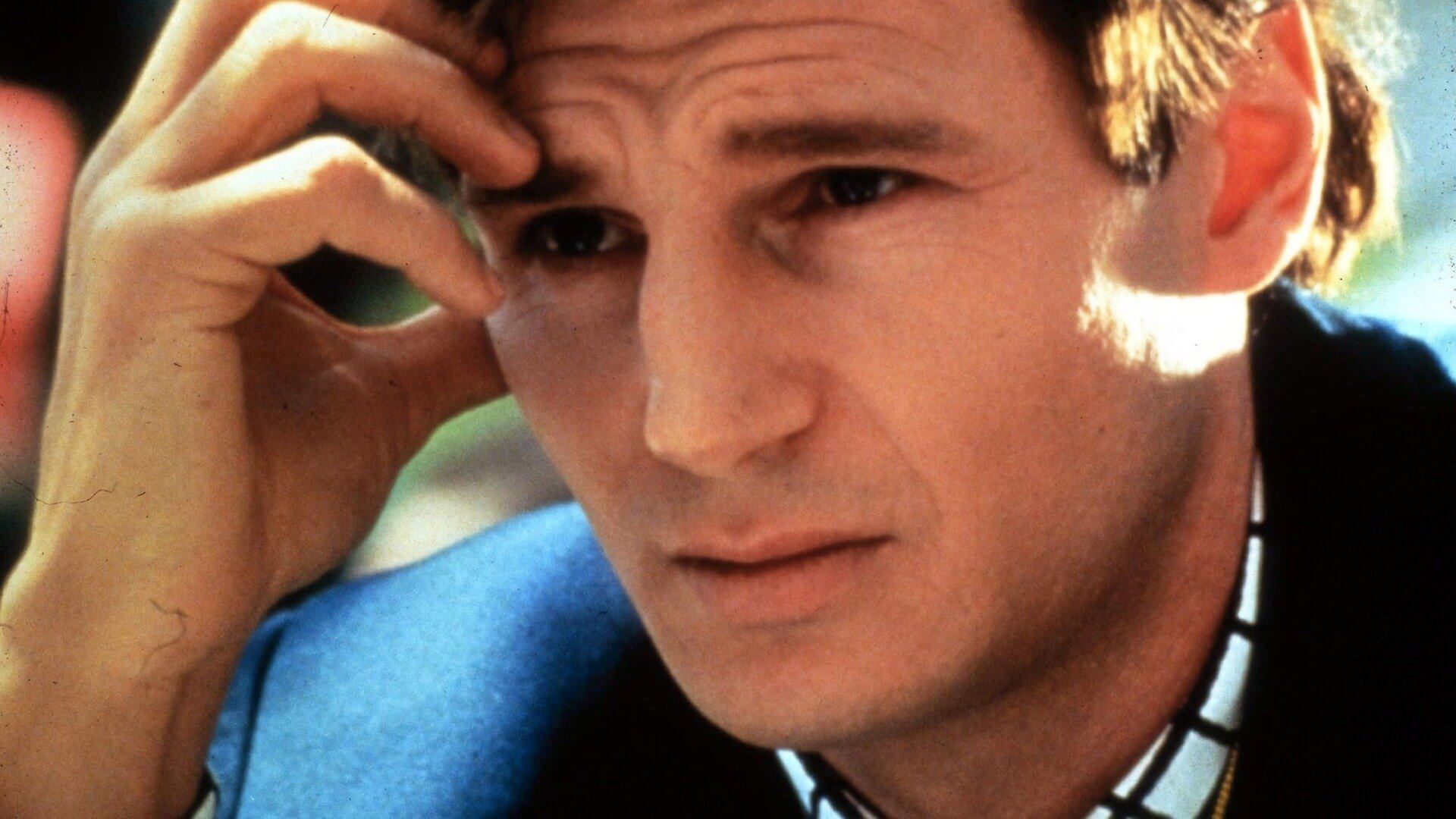

After my last viewing, I also noticed how much Raimi draws from the Universal Studios horror tradition of the 1930s (no wonder the same studio produced Darkman). This is most evident in the silhouette of the main character – Westlake appears to be a direct descendant of both Dr. Frankenstein, his monster, the Invisible Man, and even the Phantom of the Opera. He is an antihero with a monster and lover in his soul, someone who kills with a smile on his face but is also aware of his own descent. Unlike those horror icons, we never doubt that Darkman is a positive character, although Raimi and the lead actor, Liam Neeson, often emphasize the main character’s madness. In this regard, my favorite scene remains the visit to the amusement park, where Westlake loses control and breaks the fingers of an exceptionally unpleasant park employee as if they were made of rubber. This moment is exaggerated, grotesque, shocking, but also funny – a brief sample of tonal disruption that encapsulates the entire film in just a few seconds.

This makes Darkman decidedly more entertaining than gloomy, even though it tells the story of an unbalanced hero who has had his normal life and humanity taken away. Raimi treats his first cinematic comic book adaptation in this way, focusing more on visual storytelling than dialogue, which also harks back to the tradition of old cinema. However, the director of The Quick and the Dead wouldn’t be himself if he didn’t infuse this story with energy and visual flair, finding the perfect balance between melodrama and action. The camera work and framing are often unconventional, emphasizing the story’s artifice (Bill Pope, the future cinematographer of The Matrix and Edgar Wright’s films, is responsible for the cinematography). Some of the visual effects, already glaringly artificial at the time, primarily signal the medium from which Raimi drew his greatest inspirations. The film is complemented by Danny Elfman’s music, which is strikingly similar to his score for Tim Burton’s Batman from a year earlier. It builds the atmosphere but also takes center stage, giving the scenes the appropriate emotional tone.

Is Darkman as enjoyable to watch today, mor then 30 years after its release, as it was back then? It still impresses with the typical Raimi energy, but I admit it has aged a bit in my eyes. It can be criticized for its narrative simplicity and naivety, the cheapness of some visual effects, and the caricature-like qualities of the main character in a few moments, although all of these elements also contribute to its originality. Also, by today’s action standards, there isn’t all that much action here. Nevertheless, the helicopter chase sequence with Darkman hanging on a rope is still incredibly impressive today, as it was mostly done as a stunt without the use of computer-generated effects, which would be mandatory nowadays. On the other hand, brutality is surprisingly pervasive here, partly mitigated by a thick layer of dark humor – even in the scene where Westlake is tortured, the absurdity of the whole ordeal tempers the cruelty.

It’s interesting to see Liam Neeson in his first “action” role, long before Taken and the flood of similar films; the actor seems to be having a great time and fits the genre perfectly. An even bigger surprise is the presence of Frances McDormand, a two-time Oscar winner, in a role so different from the ones we know her for. She later admitted that she was miscast in Darkman, trying to make Julie more than just a damsel in distress. The role of Durant, the dangerous man who enjoys cutting off his victims’ fingers, was played by the late Larry Drake (and is it just me, or does his character resemble the comic book Kingpin, the elegant crime lord?). Keen eyes will also spot Ted Raimi on screen as one of Durant’s henchmen, as well as John Landis, Jenny Agutter, and the director himself in cameo roles. Bruce Campbell also makes an appearance, although in a much smaller capacity than Raimi had wanted – the actor known for Evil Dead was the first choice to play Westlake, but the studio deemed him not famous enough. Nevertheless, his appearance is a true treat for fans.

Compared to the later comic book wave, of which Raimi was also one of the main contributors (after all, he directed Spider-Man in 2002 and its two sequels), Darkman stands out as a work that transcends the genre. It strikes at the current extravagance and spectacle of comic book adaptations, equally willing to experiment with visual style as it is with the character of the main hero, who is far from the typical comic book hero. In the end, even Darkman found his place in comics, getting his own comic book series. There were also two direct-to-video sequels, with Arnold Vosloo replacing Neeson, but they are not widely regarded as successful.

In a recent interview with the creators of the original Darkman, we learned that the film, in its initial form, had a runtime of two hours, and the version that ultimately made it to theaters was not the one the studio had agreed upon. Raimi, producer Robert Tapert, and editor Bob Murawski (completely unrelated to the project but who has been collaborating with the director since then) secretly re-edited the film shortly before its release. Therefore, it’s difficult to say how much we would have gained from Raimi’s original version and how much we would have lost if Universal had stuck to its guns.