CANDYMAN (1992). One of the most important horror films of the 90’s

…, and horror became mainly associated with lavish adaptations of famous gothic tales (such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula, Kenneth Branagh’s Frankenstein, Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire, and, a bit later, Stephen Frears’s Mary Reilly), it was easy to understand the need for changes in a genre that had somewhat come full circle, relying on classic texts and those corresponding to the classics. However, before the postmodernist resurgence arrived (especially thanks to Wes Craven and his New Nightmare and Scream), we received one of the most intriguing and fondly remembered horrors, intelligently attempting to challenge the foundations of fantasy horror. Although Bernard Rose’s Candyman stops halfway between being an outstanding representative of its genre and a standard monster scare, it’s a title that should be known.

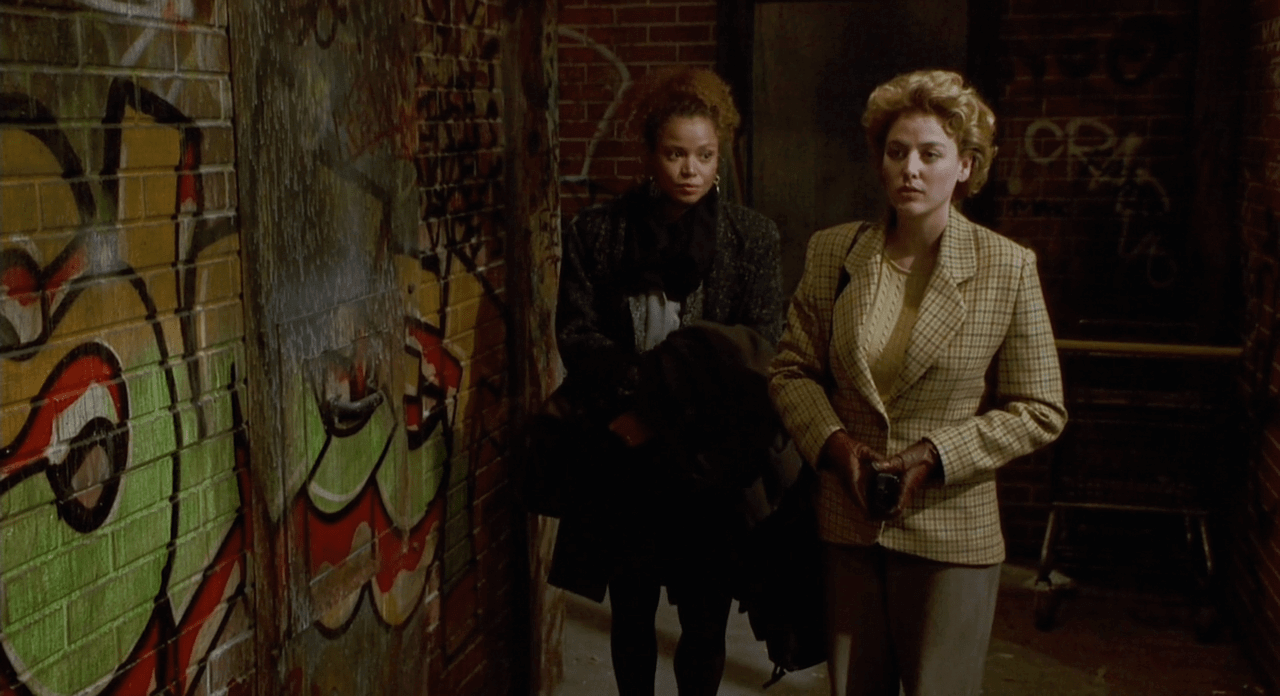

Helen Lyle, who is working on her doctoral thesis about urban legends (superbly portrayed by Virginia Madsen), along with her best friend and crime partner, Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons), stumbles upon the legend of Candyman, a monster that appears in the mirror when you say his name five times, only to gut you with a bloody hook. They quickly discover that the legendary figure is most feared by the residents of the Cabrini-Green housing projects in Chicago, where many murders have been attributed to the mythical monster. Helen, in particular, becomes deeply involved in the case, even leading to the arrest of a man who falsely claimed to be Candyman, but who was actually a member of a local gang. Soon, however, she is haunted by a tall man dressed in old fur, with a bloodstained hook…

This horror, based on Clive Barker’s short story, begins to instill an unsettling feeling in the viewer from the very beginning, even during the opening credits. Philip Glass’s organ and choral music takes the forefront as we see the city from an aerial perspective on screen. But there is something unnatural about these shots – the vertical framing makes the typical scenery appear alien to us, and the sounds associated with a church suggest a perhaps divine perspective. However, a male voice soon explains that blood is meant to be shed and the hook is meant to rip apart human bodies. This is no god, but Candyman, although he later refers to people who believe in his myth as “devotees.” During this narration, we see a swarm of bees on the screen, suddenly rising into the sky and creating a dark canopy above the city. This image is not explained within the plot but serves as a clear foreshadowing of the horror to come.

Returning to the unusual framing at the beginning, it translates into the construction of the entire film. The British director, known for his excellent fantasy drama Paperhouse shot earlier, clearly distinguishes between the unnatural and the supernatural – he forsakes the latter and focuses on the most realistic portrayal of the story, using fantasy only when necessary. For a good part of the story, there isn’t even a need for it. We witness Helen’s investigation, as she tries to deconstruct the urban legend of Candyman from the inside, attempting to uncover not so much who the murderer with the hook is (was), but how human imagination works and the power of gossip. She not only dismisses the possibility of the monster’s existence (we quickly see her say his name five times in front of a mirror) but also makes others stop believing, especially when the police catch the gang leader who liked using the hook.

As important as the legend itself is the place where it is spread so frequently. The Cabrini-Green housing projects are home to a poor African-American community, among whom there are often criminals. The Candyman myth can explain any unexplained murder, shift all blame onto the spectral killer, and make him a daily threat; all to make people fear the actual, non-fantastic danger less. Since reality overwhelms them, it’s easier to turn to the fairy tale, no matter how cruel it may be. Or is it the other way around, and the myth has become popular because of excessive crime, the evil present every day? Rose wisely uses authentic locations, not trying to exaggerate the dangers they carry. He relies on the truth, which keeps the journey of Helen and Bernadette through the corridors and deserted apartments in search of traces of Candyman’s presence (or rather absence) in unceasing tension.

The effectiveness of the first 45 minutes of the film also comes from the fact that, up to this point, we don’t see the titular character. We get to know him only through verbal communication; he is a story that lives through the courtesy of everyone who tells it to another person. But there is also fear because, after all, this ghost exists to invoke terror at the mere mention of his name. Take that away, and he ceases to be. And then, at the most critical moment, he reveals himself to show what he truly is.

Because the beginning of the film is incredibly suggestive and credible, what happens later hits the viewer all the harder. Candyman reveals himself to Helen, accusing her of disbelief in him, for which he decides to exact a beautiful revenge, making her the prime suspect in a kidnapping and murder case. Since she questioned his credibility, he will do the same to her. Doubts arise quickly because, for a classic boogeyman, this is a surprisingly devious (and not very horror-like) plan. The further the story unfolds, the worse it gets – initially, we think it’s revenge on a woman, then there’s a promise to turn Helen into another urban legend, and finally, the suggestion that she may be a reincarnation of his great love when Candyman was still a man. It’s difficult to see him as an avenging angel against the white community for years of persecution and his own death, especially when he guts his victims without regard for their skin color.

Moreover, the character portrayed by the charismatic Tony Todd is a being with a very ambiguous ontological status. On one hand, he can appear wherever and whenever he wants, going unnoticed by anyone except Helen, raising suspicion that he is only a product of the woman’s imagination. On the other hand, we see him sleeping (!) in his hideout, and the main character’s theory that the killer uses the passageways behind the mirrors in every apartment is confirmed. The way Rose constructs the scenes in which Candyman appears is surprising in the sense that, as I mentioned before, realism prevails over fantasy. Even when we observe a swarm of bees flying out of his mouth, it feels authentic. It’s not the supernatural presence of the titular character that is striking but the fact that it has become a part of the real world so effortlessly. The myth has come to life and, as a result, has ceased to be a myth.

There is, therefore, a certain inconsistency regarding Candyman in the second half of the film, as well as the replacement of the very atmospheric and unconventional horror with scenes of the character’s bloody activities, which turn the work of Rose into a common slasher. Thus, while up to the moment of the monster’s first appearance, the story focuses on the attempt to debunk his legend, later on, we witness the birth of a new one. Suffice it to say that after the ending we receive, it’s difficult to think about typical sequels, which were, however, made. In a thoughtful way, the director replaces one ghost with another, and the residents of Cabrini-Green stop associating the vengeful apparition with the black giant. They no longer believe in it – the hook ultimately lands in the hands of a new owner.

30 years after its premiere, Candyman holds a surprisingly low place among perhaps the most important horror films of its decade. It is, of course, remembered, but not necessarily for what it should be – everyone associates the hook and the utterance of the ghost’s name in front of the mirror, whereas the creators of the film are most interested in attempting to debunk the urban legend, which has the strongest impact on the viewer. This is what sets Bernard Rose’s work apart from the two unfortunate sequels, which focused solely on gruesome attractions (it’s worth noting that Bill Condon, the creator of the wonderful Gods and Monsters, a drama about the twilight of James Whale’s life, and the live-action version of Beauty and the Beast, was responsible for the second part). The original Candyman, although it does not shy away from gruesome moments and vivid characterization, opts for horror more firmly grounded in reality than the fantasy of something like A Nightmare on Elm Street. It doesn’t even make an effort to distinguish between reality and dream, truth and falsehood – it’s as if the titular monster exists regardless of whether we believe in it or not.