AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON. Second best werewolf horror

… and for many, it’s the number one among werewolf movies. If I were being malicious, I would write that the reason for this is rather the poor quality of most films whose main theme is the transformation of a person into a hairy beast. Among the most successful ones, we should mention, above all, Joe Dante’s The Howling (1981), and Mike Nichols’ Wolf (1994), and later, John Fawcett’s Ginger Snaps (2000), Neil Marshall’s Dog Soldiers (2002), and perhaps one of the classic werewolf films, be it from Universal or Hammer studios. And although horror is Landis’s primary genre, the strength of his film comes from the fact that while it is also a comedy, it doesn’t reveal where the horror ends and the joke begins.

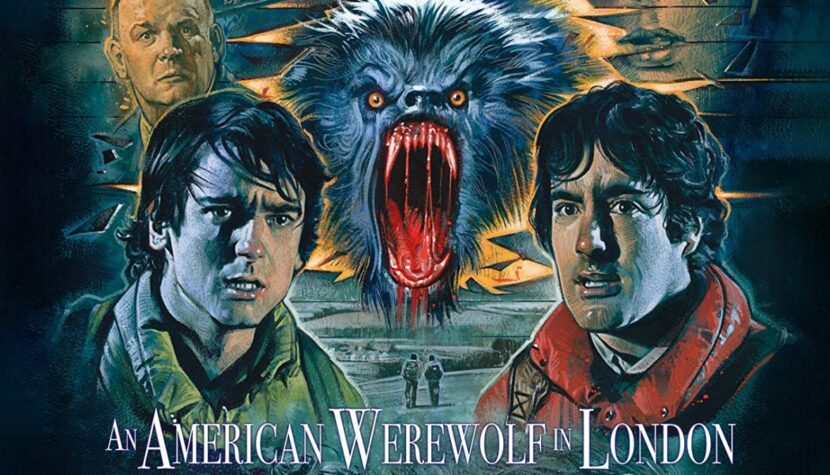

The titular American is David (the excellent David Naughton), who, along with his friend Jack (Griffin Dunne, After Hours), is attacked by a werewolf during a trip through the English countryside. Jack dies on the spot, while David escapes with minor injuries and ends up in London. In the hospital, the protagonist forms a close relationship with the nurse taking care of him, Alex (the wonderful Jenny Agutter, known for Walkabout and An American Werewolf in London). He also encounters the ghost of his deceased friend, who warns him that during the next full moon, David will transform into a beast.

On one hand, the film follows a very classical narrative structure for this type of story— the protagonist attacked by a werewolf ultimately transforms into a monster and, at the same time, finds the love of his life, heightening the tragedy of the situation. It’s not hard to predict how it will all end, especially since Landis is a big fan of conventions, as evidenced by his 2011 book Monsters in the Movies, a guide to the most famous movie monsters. However, in 1981, Landis was primarily known as a comedy director, having achieved success in the United States with Animal House (1978) and the worldwide cult hit The Blues Brothers (1980). Moreover, he was still to release Trading Places (1983), Spies Like Us (1985), Three Amigos (1986), and Coming to America (1988). Based on these titles, Landis can be confidently considered one of the most important American comedy directors of the 1980s. His An American Werewolf in LondonAn American Werewolf in London seemingly deviates from this lineup, yet from the very beginning, it’s a horror film filtered through the mischievous imagination of its creator.

Starting with the balance between not only horror and comedy but also different types of humor, the choice of songs for the soundtrack, the majority of which have the word “moon” in their titles, to the ending, so abrupt that when the end credits roll accompanied by a rock and roll classic, we are immediately taken out of the film, Landis’s work has an element of humor that isn’t always readily understood. The cameo by Frank Oz (whose voice is known to fans of Yoda and Miss Piggy) as a horrified embassy official witnessing David’s hysterical behavior when he learns of his friend’s death is just as surprising as the superb nightmare scene with Nazi monsters exterminating the main character’s family in their suburban American home. When the character wakes up, and we think we’ve escaped from his gruesome dream into the real world, Landis serves up another surprise. This tonal rollercoaster of An American Werewolf in London, consistently maintained, becomes a defining element of the film, with its jokes often punctuated by jump scares and horror pushed to the brink of absurdity.

But when needed, Landis is serious. In the An American Werewolf in London ‘s most memorable scene, the one that earned Rick Baker his first Academy Award for makeup effects (in a category that, up to that point, had not existed at the Oscars), David’s transformation into a werewolf unfolds before our eyes, and it’s an excruciating process for him. The music playing in the background again seems inappropriate for what we see on the screen, but there is nothing funny about the protagonist’s terror, even when he breaks the fourth wall, reaching out to the viewer and looking directly into the camera. It’s a risky move, one that could have turned into another joke, yet thanks to Naughton’s convincing performance, Baker’s groundbreaking effects, and Landis’s incredible directing talent, this moment leaves a profound impact. Perhaps also because comedy was so prevalent in the film, this scene hits even harder – we expect the director to break the horror with humor at any moment, but it doesn’t happen, and the transformation into a beast unfolds powerfully, accompanied by the screams of the main character.

Subsequent scenes of An American Werewolf in London heavily rely on humor derived from the British mentality, which dictates responding to potential threats in an unemotional and authoritative manner until the victim realizes they are face to face with a monster. However, the horror promise in the title doesn’t need to be taken literally – David is portrayed as a brash (though always likable) American in a place where everyone around him behaves reservedly. He doesn’t need to transform into a werewolf to be a completely different creature from the more civilized Englishmen. Are they really like that? Landis isn’t interested in answering that question, although the Mark Twain read by Alex A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court suggests that beneath the veneer of a satirical tale, there may be some reflection.

However, I don’t believe in that very much. An American Werewolf in London lacks significant ambitions – the text doesn’t carry interesting observations about the differences or similarities between human and animal nature or the collision of two entirely different cultures. All of this serves only for entertainment, often bloody and humorous through the accumulation of elements that simply don’t fit together. The only value that can be observed during the viewing is shock value – regardless of whether a scene is more comedic or horror-oriented, its final effect should be sudden, unexpected, and often unsettling for the viewer.

Landis attempted the same trick in Innocent Blood (1992), but the film about a vampire killing gangsters was already devoid of the energy and shock characteristic of his An American Werewolf in London. Much better in this regard was the last film in the American director’s career, Burke and Hare (2010), although comedy clearly dominated over horror here. And only once did Landis want to scare us without relying on humor – in his segment in the movie Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), the main character, a racist, assumes the roles of representatives of the races and nations he despises: a Jew during World War II, an African American persecuted by the Ku Klux Klan, and a Vietnamese person. It was a thought-provoking story but gained notoriety due to the tragic on-set accident in which the lead actor Vic Morrow and two children were killed.