THE NEVERENDING STORY Explained: A Timeless Fairy Tale

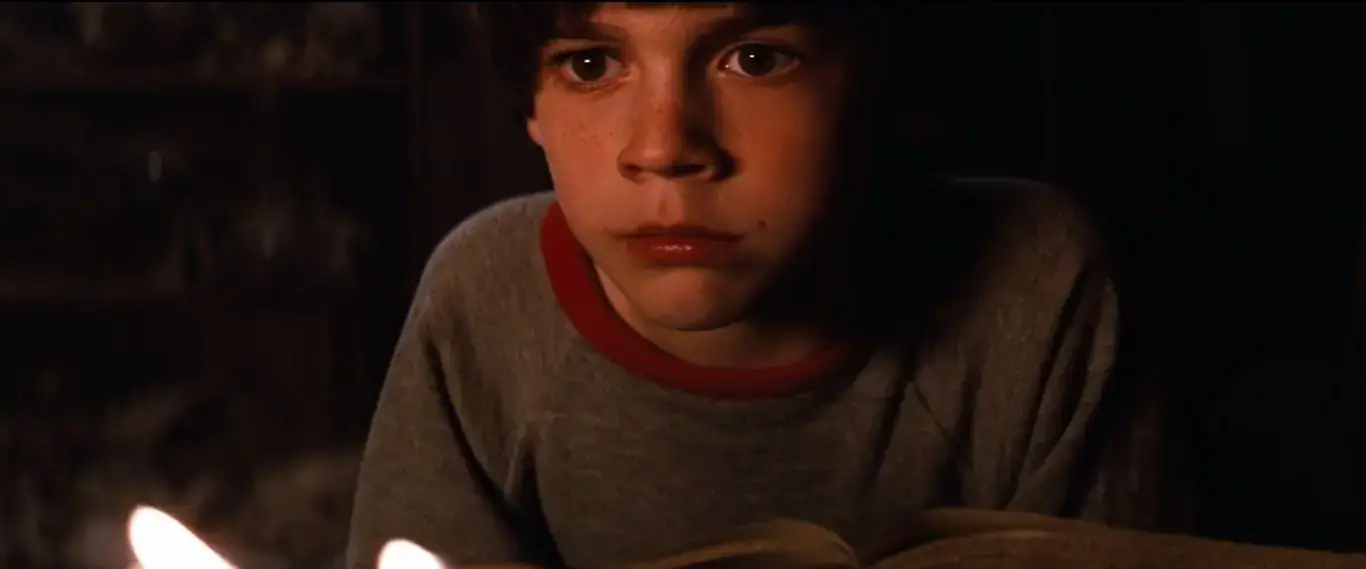

Whether our parents took us to the cinema to see them or we watched them on TV while building the next architectural wonder out of Lego bricks, they somehow became etched in our memory and probably will never leave it. For the Polish generation of people in their twenties and thirties, one such title is The NeverEnding Story by Wolfgang Petersen. The tale of the brave Atreyu, who must defeat the all-consuming Nothing that threatens to engulf the magical land of Fantasia, was at the time of its release (in 1984) the most expensive film ever produced outside the United States and the Soviet Union. The film cost 60 million marks, which, at the exchange rate of the time, was equivalent to 27 million US dollars.

Today, that sum no longer makes much of an impression. However, we must remember a few facts. In Petersen’s film, you won’t find big stars commanding astronomical fees for their performances. The Deutsche Mark no longer exists, and the value of the dollar has significantly changed. After all, The NeverEnding Story was primarily aimed at a youth audience, so its potential viewership was quite limited.

The main producer of the film, Bernd Eichinger, was well aware that the story of Atreyu could sink not only him but also other serious investors putting their money into the completion of the movie. The German market had no chance of covering the production costs, let alone generating any profit. That’s why Eichinger from the beginning counted on The NeverEnding Story succeeding across the ocean. For this reason, the lead child roles were played by actors from California. Moreover, the American cast wasn’t the only nod to the Western audience. The American version of the film also differed in terms of its soundtrack. While the original German version featured only the instrumental music by Klaus Doldinger, the “American version” was enriched with elements of techno-pop and the famous song performed by Limahl and Beth Anderson (worth mentioning, the composer of the song was Giovanni Giorgio Moroder)

In retrospect, we know that the creators somewhat misjudged the financial potential of the US market. The film debuted there on July 20, 1984, eventually earning around 20 million dollars, which — by American standards — was not a staggering amount. The film made about the same amount in Germany. It was seen by about five million cinema-goers there (which was, by contrast, a considerable success). What truly surprised the producers, however, was the film’s success in other markets. Outside of Germany and the USA, the movie brought in an additional 60 million dollars, making The NeverEnding Story a financial success.

Adaptation

The warm reception of the film did not save it in the eyes of the book’s original author, Michael Ende. One of Germany’s most popular writers of children’s and youth literature, he sharply criticized the project even before its completion. He was unhappy with the significant changes compared to the novel and the film’s visual style. Ende insisted that his vision of the land of Fantasia was built on mystery and ambiguity. Petersen and his team’s vision was, for him, too literal and even kitschy. For example, he compared the Ivory Tower (the heart of the land and home to the Childlike Empress) to a TV tower with interiors resembling a nightclub. He also sarcastically commented on the Sphinxes guarding the entrance to the powerful oracle, criticizing their exposed, feminine breasts. Ende’s main criticism, however, was directed at the depiction of the Nothing, which for him didn’t resemble a menacing force but rather a quiet, gradual erasure of reality — something closer to the loss of memory than a progressing disaster.

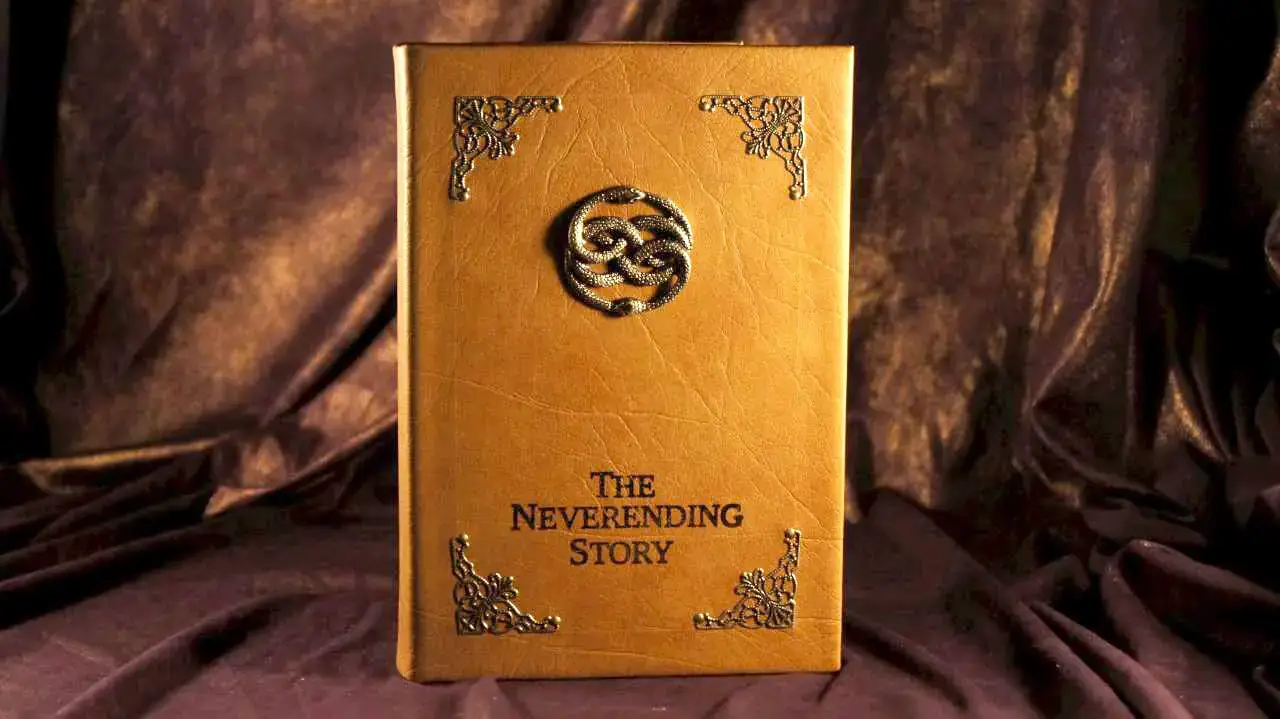

The difference in opinion between the author and the film crew was so great that Ende demanded the cessation of filming or a change in the title and the removal of his name from the credits. The first option was, of course, out of the question. Too much money had already been invested in The NeverEnding Story to halt the film’s production. The creators also didn’t want to give in regarding the film’s title. Ende’s book, published in 1979, had already garnered a significant fanbase (even beyond the borders of West Germany), so changing the title for marketing reasons would have been a serious misstep. The whole matter ended up in court, where Michael Ende lost the case.

Of course, many people familiar with the novel point out numerous simplifications in the film compared to the original. Moreover, supporters of the book version are probably right in this regard. Petersen’s film adapts only the first part of Ende’s text, completely omitting the second part, which focuses on Bastian’s presence in Fantasia. This decision turns The NeverEnding Story into a tale much more firmly set in the framework of a classic fairy tale, featuring the dynamic of “zero to hero” and the unequivocal triumph of good over evil. Ende’s text, in this aspect, was much more subversive. After entering Fantasia, Bastian turned into an anti-hero, deluded by the magical power of Auryn. Atreyu, after defeating the Nothing, had to confront the gradual change in Bastian’s character. Ende suggested that imagination and fantasy could both destroy and create. Everything needs moderation; one must be cautious.

In hindsight, it is difficult to understand the author’s hostility towards the film adaptation. It’s hard not to feel that megalomania, which often appeared in the statements of The NeverEnding Story’s author, came to the forefront here. By agreeing to the adaptation, Ende must have realized that not everyone sees Fantasia the way he did while writing it. Adaptations follow their own rules. The hostility is even more surprising considering the passion and dedication of the team working on the film. Besides, the completed film stands on its own merit.

Creating Fantasia

Even though the visual aspects of The NeverEnding Story have begun to show their age, it’s hard to deny the film’s enduring charm. This is undoubtedly due in part to nostalgia, but it’s also important to remember that at the time of the film’s release, epic fantasy movies were just beginning to make their mark in cinemas. Of course, the history of such films goes back much further (consider Fritz Lang‘s monumental Die Nibelungen or the American epics of the 1960s), but the release of The Empire Strikes Back in 1980 seems to be a pivotal moment in their development. The debut of Irvin Kershner’s film set certain trends. Fantasy worlds became a fusion of various forms of art and technology. Their creation was not only in the hands of set designers and costume makers but also involved computer graphics specialists, puppet creators, and mechanical effects experts. Productions from the 1980s, like Ridley Scott’s Legend, David Lynch’s Dune, and Wolfgang Petersen’s The NeverEnding Story, fit into this new trend of filmmaking.

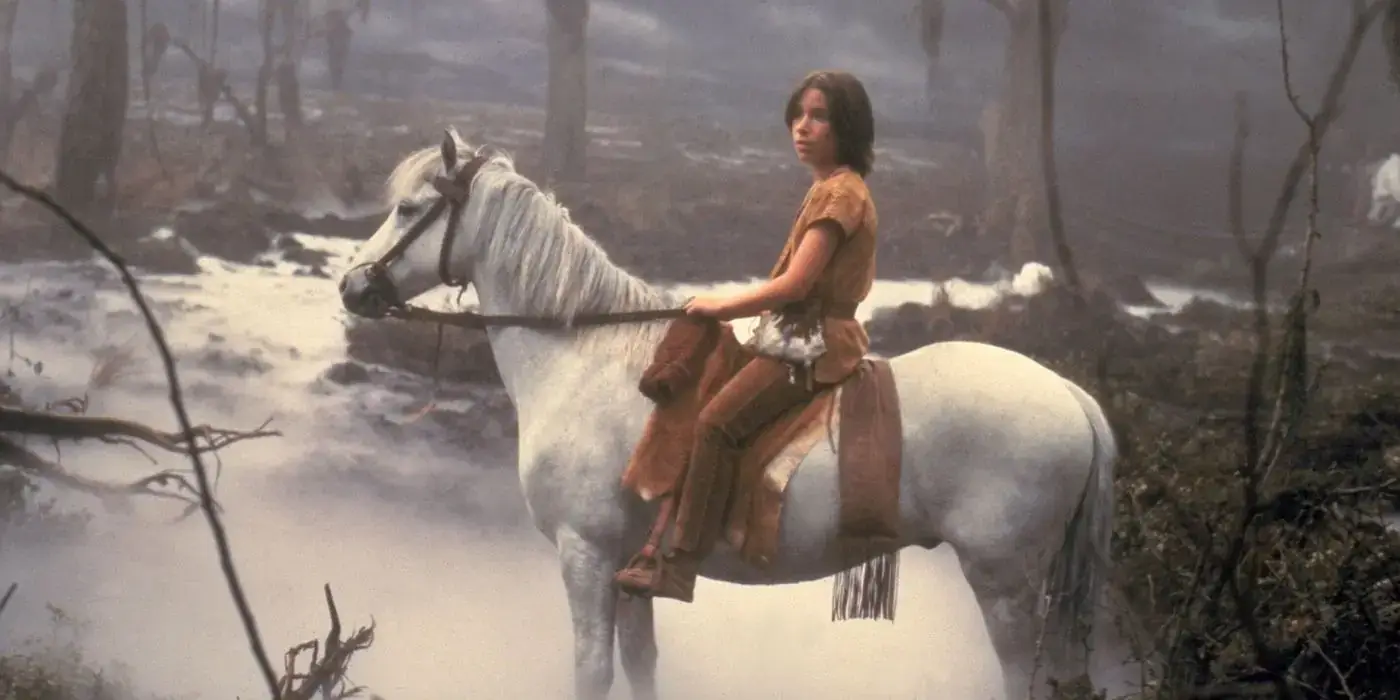

Despite comparable budgets between The Empire Strikes Back and The NeverEnding Story, the story of Bastian has aged more rapidly than the second installment of the Star Wars saga. However, it’s still worth noting the immense effort that went into the visual presentation of Petersen’s film. The desire for complete control over the filmed material led to the construction of Fantasia in one of the largest film studios in Europe. Only the scenes with Bastian (the boy reading the book in the school attic) were filmed outside Europe, in Canada. Inside the studio, they shot scenes like Atreyu traveling through the Swamps of Sadness, an obstacle in his journey to find the all-knowing Morla. For these scenes, tons of mud, peat, and gallons of water were brought into the studio to create a convincing replica of real wetlands. The most crucial moment in the swamp—the drowning of Atreyu’s horse, Artax—was achieved through the collaborative efforts of a professional horse trainer, roboticists, and set designers. During the sinking sequence, the horse stood on a special pneumatic platform that gradually lowered it into the mud (the trainer worked with the animal for two weeks to ensure it wouldn’t panic during the descent). During one take, a near-disaster occurred when a malfunction in the pneumatic system almost resulted in Noah Hathaway, who played Atreyu, being pulled underwater. Although the Swamps of Sadness sequence makes up only a small portion of the film, filming this segment took over four weeks and cost more than $120,000.

The malfunction of the swamp platform wasn’t the only accident on set. Hathaway also had bad luck with machines built by the mechanical effects specialists. Another incident occurred during the scene where Atreyu confronts the giant wolf, Gmork. The creature, which could speak like a human, was actually a robot mounted on a movable structure, allowing it to lunge forward. This mechanism enabled Gmork to leap out of the cave and attack Atreyu. Petersen, who wasn’t shy about doing multiple takes, repeated the scene with Gmork several times. During one take, the robot lost control and collapsed onto Hathaway, who was lying on the ground. Thanks to the quick reaction of the crew, he suffered only minor bruises. After this incident, the director decided not to risk another take and chose from the already recorded material.

For safety reasons, Noah Hathaway didn’t perform all the scenes involving Atreyu. He was replaced by a stunt double, the 26-year-old Bobby Porter, known for his stunt work in films like E.T. and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Porter can be seen in the scene where the Nothing catches up to Atreyu, causing the world around him to disintegrate. To avoid being swept away by the hurricane-like winds, Atreyu clings to a tree branch. From the viewer’s perspective, he appears horizontal, but in reality, Porter and the set were on a platform initially parallel to the studio floor and then tilted 90 degrees. The camera followed the platform’s movement, creating the illusion of a stable angle for the audience. In reality, Porter was hanging above the ground, with pieces of the set (mainly Styrofoam rocks) falling onto him, making it difficult to maintain his grip on the dry branch. Petersen didn’t skimp on additional takes, even though they required rebuilding the set after each attempt.

Gmork is just one of many extraordinary inhabitants of Fantasia. The world created by the crew is filled with a variety of characters—some played by actors in elaborate makeup (like the Night Hob and Teeny Weeny), some fully robotic (like Falkor the luckdragon and the bat used for transportation), and others that combined both approaches (like the Rockbiter). Bringing these robots to life required a whole team of people. For example, bringing Falkor to life required a dozen or so people working simultaneously at control stations connected to the dragon via cables, synchronizing the movement of each part of his body. The facial expressions of characters like Gmork and the Rockbiter were controlled remotely, with electronic mechanisms enabling detailed movements. There were two models of the Rockbiter: one for mobility, operated by a specialist inside, and another, more flexible version used for close-up facial shots.

In discussing the film’s unique effects, it’s worth mentioning the “villain” of the story: the Nothing. The eerie sky heralding the arrival of this catastrophe was not achieved through computer graphics but through the ingenuity of the crew. Each scene showing the ominous clouds was filmed using a tank of water with dye, viewed through a plexiglass panel. The only scenes where computer-generated effects played a significant role were Atreyu and Bastian’s flights on Falkor (where footage of the actors was combined with aerial shots or scenes filmed in a water tank) and various electrical discharges like lightning or laser beams from the Sphinxes’ eyes. It’s no surprise that these segments are the ones that have aged the most.

A Touch of Nostalgia

Even after reading Michael Ende’s novel and realizing that Petersen’s film adaptation is far simpler and more one-dimensional, it doesn’t change one important thing for me: The NeverEnding Story still works wonderfully as a timeless fairy tale. The story of Bastian and Atreyu continues to awaken the child in me who used to build Lego creations and snack on Kinder Surprise while watching the film, and that feeling is sometimes more valuable than wandering through the philosophical depths explored in Ende’s original. There’s also one more reason I still feel drawn to these kinds of productions. It’s nice to look at the set photos and see something tangible and real instead of something purely digital.