THE BIG BLUE Explained: Incomprehensible, Yet Beautiful

In 1989, Raphaël Bassan, one of the most influential French critics devoted to exploring new forms of cinematic expression, declared that another New Wave had begun to wash up on the shores of the French Riviera. Cinéma du look was to be the voice, or perhaps the scream, of young people suffocating in a country governed by François Mitterrand. The protagonists of films belonging to this movement were often outcasts, drifting through the streets and metro stations like sleepwalkers, unable to connect with their families or with the reality of 1980s France. Their stories were meant to be told without too much emphasis on complex narratives and intellectual twists. What mattered was the impact on emotions, the style. The so-called “big three” of Cinéma du look were quickly recognized as Luc Besson, Jean-Jacques Beineix, and Leos Carax.

The films created by these young directors in the 1980s indeed shared a common thread. They mixed high and low culture, displayed a fascination with the West, and featured the kind of characters and themes that Bassan rightly recognized as the birth of a new trend. However, during this period, Luc Besson made a film that defies any easy categorization. The Big Blue indeed carries the spirit of its time, but ultimately, it stands as a one-of-a-kind film. One could try to fit it into the prevailing trends of that era, find the appropriate boxes in the massive files of film history. But it’s important to remember that freedom, like water, can’t be confined to a wooden drawer in an archive.

Luc, Jacques, and Enzo

Luc Besson was not the kind of person who knew from a young age that his future would be connected to the arts. For a long time, cinema was not among his interests. His childhood was filled with completely different activities. Besson’s parents were diving instructors, so young Luc often found himself underwater. Due to his parents’ passion and profession, he frequently visited Greek and Balkan beaches, becoming deeply addicted to the world that lies beneath the waves. After his parents’ divorce (when Besson was ten), the ocean became his escape and a way to forget his troubles. There was a strong possibility that he would pursue a career related to the sea. However, his diving career came to a halt at age seventeen due to a serious accident. Besson had to abandon his underwater adventures. As he recalls, he was devastated but decided not to give up. He sat down, took a piece of paper, and started listing his strengths and weaknesses. The self-reflection led him to conclude that he needed to make films. Much to his mother’s dismay, he dropped out of school and began working on film sets, often serving coffee on semi-amateur projects. The first ideas he scribbled down would soon become some of his greatest successes—The Fifth Element and The Big Blue.

Besson’s desire to create a film about two divers was born before he turned twenty. He came across a French documentary about Jacques Mayol, one of the pioneers of deep diving without oxygen tanks. After watching it, he knew he had found the protagonist of one of his future films. Nearly a decade later, after completing the successful Subway, Besson fulfilled his youthful dream by starting production on The Big Blue. Moreover, Jacques Mayol himself, the man who inspired the film, helped Besson with the screenplay.

The storyline was based on the rivalry between two exceptional divers. We already know one of them; the other was Enzo Maiorca, portrayed in the film as Enzo Molinari, the best character brought to life by Jean Reno. Maiorca’s name was likely changed because, for a long time, he objected to how his character was depicted as too caricatured. He only softened his stance toward the film in 2001, after Jacques Mayol’s tragic death by suicide.

The Big Blue has much in common with reality, yet it is by no means a film that strictly adheres to the facts of these two great divers’ lives. Mayol and Maiorca indeed competed to see who could dive deeper, but their rivalry was never as direct as portrayed in the film. In reality, both divers operated independently, learning about each other’s achievements from the press, television, or word of mouth. Because Mayol worked on the screenplay and because Besson viewed him as the film’s main inspiration, Mayol’s character is closer to reality. Maiorca, or Molinari, is drawn with a bolder brush, emphasizing his competitive nature and desire to be the best. That drive was what originally inspired young Maiorca to begin his journey into diving (after reading an article in 1956 about someone breaking the forty-meter mark, he felt he had to be “the man who went deepest”). Besson also doesn’t overlook that beneath the bravado of a sportsman lay a sensitive person, which Jean Reno’s performance brilliantly conveys, especially during the bitter conclusion of his rivalry with Mayol.

The film’s depiction of Jacques Mayol (played by Jean-Marc Barr) is more subtle. Insight into his character is provided by the brilliant soundtrack composed by Eric Serra, one of the best musical accompaniments in cinema history. One of the tracks is titled Homo Delphinus, a nod to Mayol’s book of the same name, in which he philosophically ponders whether humans might have an inherent, though hidden, connection to the ocean—a trait that would allow them to function naturally in the sea. Though such ideas may seem surreal, scientists partly confirm Mayol’s suspicions. Biologists agree that mammals, including humans, possess a natural dive reflex that adjusts the heart’s function when submerged. Mayol himself was the best example of this instinct; during dives, his heart rate would slow down, beating as low as 27 to 60 beats per minute depending on depth, water temperature, and effort.

The fates of the divers in the film differ significantly from reality. Enzo Maiorca is still alive today, while Jacques Mayol, after battling depression, took his own life in 2001. His ashes were scattered on the coast, echoing the ambivalent conclusion of Besson’s film and Molinari’s words: It’s much better down there. It’s a better place…

Different Shades of Blue

The Big Blue is undoubtedly a beautiful film, but it is also profoundly ambiguous, leaving far more questions than answers. To simply call it a film about diving is like saying The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann is a story about a stay at a mountain sanatorium. It’s a film about the pursuit of freedom, a longing to reconnect with nature, and the sacrifices made for passion. Love, friendship, and the struggle to conform to the social norms of life on land all play significant roles. It’s a story of individualism, but one that isn’t tainted by simple optimism suggesting that just being yourself and moving forward is enough to be happy. Because amidst all those beautiful slogans, it’s important to realize that The Big Blue is, in fact, a deeply melancholic film. And this sadness isn’t just about the fate of the main characters, but in the way that every beautiful thesis in the film has its antithesis. Sometimes it’s subtly hidden between the scenes, and other times it’s presented quite directly. The best example of this is the final scene, where Jacques is suspended in the dark ocean depths. Above him, Johanna and life await; below him, he feels the impossible pull of nature, and he’s caught in the middle. Is the dolphin that appears then a friend or a foe? We don’t know, and neither does Besson.

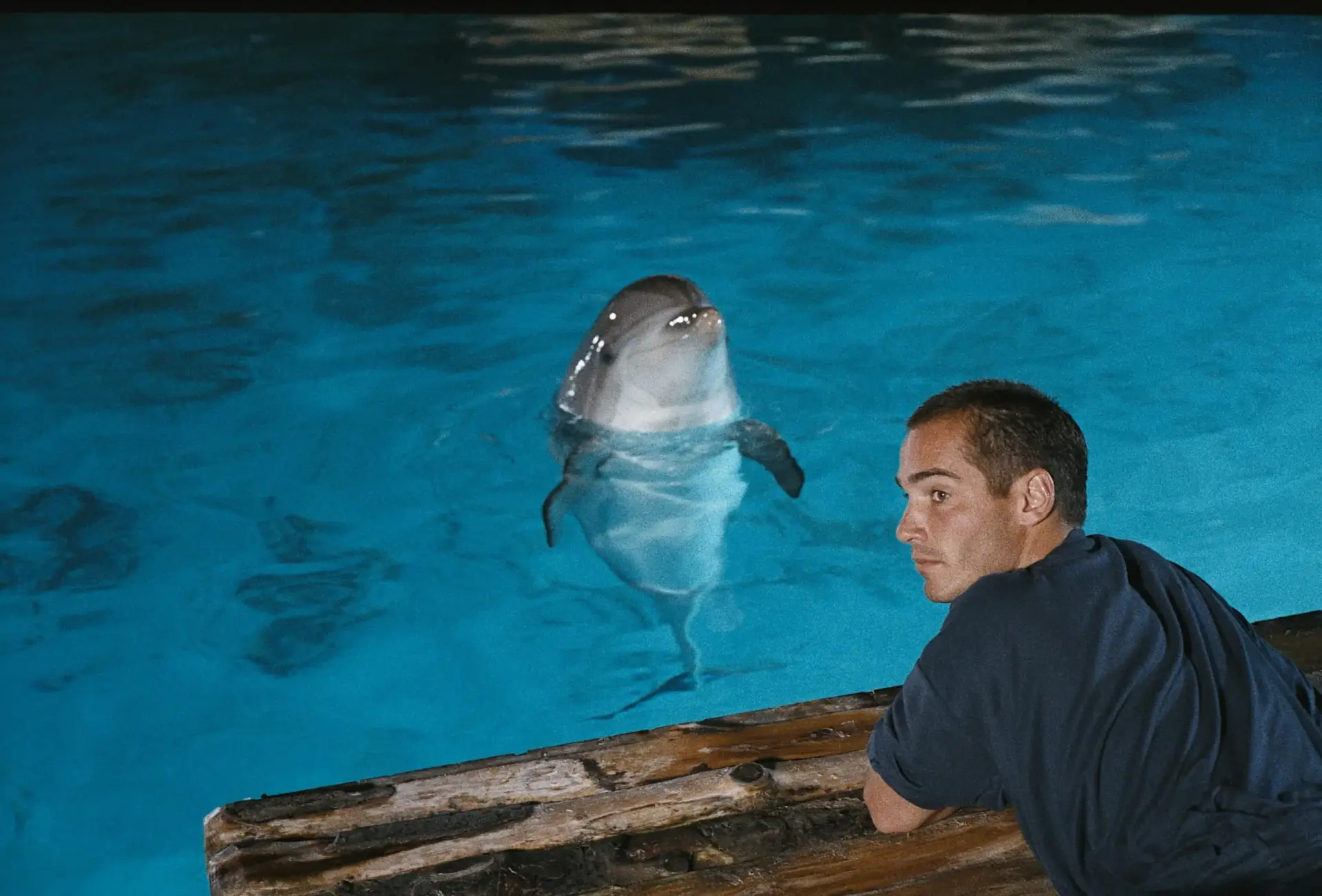

We encounter similar dilemmas at every step in The Big Blue. Take, for instance, the scene where Jacques shows a photo of a dolphin that he carries in his wallet. On one hand, the diver (like his real-life counterpart) considers these marine mammals his best friends, his family. He escapes to them whenever he can. When he drunkenly shows the photo to Johanna, he cries and questions what kind of man he is if these are the only close friends he has. Mayol, despite his great love for the ocean, is not a happy person. He’s torn between different worlds. On one side, he longs to escape civilization and all its comforts, yet on the other – like any human – he craves closeness and love. The tragedy of his character lies in the fact that, despite his sincere efforts, neither world will ever truly feel like home.

Mayol’s call of nature is not an entirely positive force. Besson understands this well and doesn’t portray the ocean’s depths as just a beautiful postcard image, like something out of a National Geographic documentary. In The Big Blue, the beauty and awe of the underwater world intertwine with scenes of impenetrable darkness that forebode nothing good—He who fights with monsters should see to it that he does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you. In a way, Mayol becomes a victim of Nietzsche’s dark prophecy. His struggle with not fitting into the world around him, with the trauma caused by his father’s death (echoing Besson’s own childhood trauma from his parents’ divorce), and with loneliness drives him toward the abyss, paradoxically wounding him even more. The wounds become so deep that they can’t be healed. Even though Jacques tries (seeking advice from Enzo about women, attempting a relationship with Johanna), nothing works out. Ultimately, Mayol becomes the monster from the prophecy, because who would plunge into the sea while a woman bearing his child stands on the shore? Of course, nothing is straightforward, as it’s hard to tell whether Jacques dives of his own free will or if he’s compelled by that call—a call both beautiful and terrifying.

The heart of The Big Blue lies in this strange dance with death. On one side, there is joy, hope, love, freedom, breathtaking nature, Johanna’s sweet awkwardness, and Enzo’s jovial spirit that somehow fuels Jacques’s desire to live. On the other side, there is sadness, loneliness, constant struggle, life’s failures, and a nature that is strange, incomprehensible, mysterious, and therefore frightening.

In Werner Herzog‘s Encounters at the End of the World, there is a scene where a penguin breaks away from its group and begins to run toward mountains that lie dozens of miles away. A penguin specialist explains that even if we caught the bird and returned it to its flock, it would soon begin its escape again. There is nothing in the mountains that has any value from a biological standpoint for the penguin. Yet it runs towards them until it eventually dies of exhaustion. In every generation, there is such a bird. It’s sad, incomprehensible, and yet hauntingly beautiful. And that’s exactly what The Big Blue is all about.