AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD Explained: Descent Into Madness

It turned out to be a rather trivial work, intended for children to learn about explorers and their journeys. Herzog began flipping through the book, only to stop suddenly on a page mentioning Lope de Aguirre. Thousands of kilometers away, the turbulent waters were crashing against the rocky banks of the Urubamba River.

Over four hundred years earlier, these same currents had carried the rafts of conquistadors exploring new parts of South America. Aguirre was one of them. From the book, Herzog learned that the Spaniard had rebelled against his king, declared himself the ruler of New Spain and “Wrath of God,” and took command of an expedition in search of El Dorado. The director became intrigued by the figure of the conquistador and soon realized that there were not many sources dedicated to his story. In most accounts, Aguirre appeared only as a fleeting mention or a symbol of a madman who, upon encountering a foreign culture and environment, lost himself in the name of greed and a thirst for power. The story of Aguirre is thus shrouded in mystery—no one knows how much of it is factual and how much is legend, embellished with each retelling of the tale of rebellion on the road to the land of gold. Aguirre, the Wrath of God it is.

Herzog loves characters with significant gaps in their biographies—appearing from nowhere, mesmerizing, and disappearing without warning. Just think of Kaspar Hauser, who for society is born in middle age, Nosferatu appearing under the cover of night, or the lost Stroszek. Similar traits are also found in the characters of his documentaries—the old man waiting for death in Under the Volcano, Marc Anthony from The White Diamond, or the people “encountered at the ends of the world.” In this light, Lope de Aguirre fits perfectly into Herzog’s universe. The fascination with a brief passage from a children’s book inevitably had to turn into a film. But it all started rather unassumingly.

SOCCER AND FALLING LEAVES

Herzog once considered a professional career in soccer. Although his path eventually led elsewhere, in the early seventies, he still played in official matches. Before one of these games, Herzog’s team had to travel a distance of 320 kilometers, with Vienna as their destination. Onboard the bus was the whole team and a few barrels of beer, meant as a gift for their opponents. However, boredom caused by the long journey led to most of the beer disappearing before the chance to enjoy a slice of Sachertorte.

Herzog refrained from pre-match festivities, spending the journey with a typewriter. This is how the initial draft of the script for Aguirre, the Wrath of God was written on the way to Vienna. Unfortunately, some scenes penned on the bus filled with drunken players were destroyed. The culprit was the goalkeeper sitting next to Herzog, who first fell asleep on his shoulder and then made quite a mess. The director didn’t give up, though. Some of the manuscript was salvaged, and the remaining parts of the script were completed during Herzog’s stay in Austria, written in the breaks between soccer matches. By the time he finished writing, Herzog knew that Aguirre needed to have the face of a man he once lived with in a Munich apartment building.

Klaus Kinski was born sixteen years before Herzog. They lived in the same building in Munich (owned by Klara Rieth) for three tumultuous months. The unrest was, of course, due to Kinski, who occupied a small attic room (while Herzog, his mother, and his two brothers lived on the ground floor). Herzog recalls that Kinski’s room had no furniture—just bare beams and dry leaves that reached up to a person’s knees. Even then, Kinski took his acting profession very emotionally, training for hours for roles he performed in Munich’s theaters and flying into uncontrollable fits of rage when facing creative blocks. Kinski could spend forty-eight hours in the bathroom (constantly yelling), throw potatoes at a critic who used the wrong epithet to describe him, or curse out the building’s owner, who let him stay in the attic for free.

When Herzog put the final period on the script for Aguirre, the Wrath of God, he immediately felt that Kinski would look perfect in the armor of a conquistador. A copy of the manuscript was sent to him almost immediately. Two nights later, at three in the morning, Herzog received a call. After half an hour of shouting and words taken out of context, Herzog realized that Kinski wanted to become his Lope de Aguirre.

THE TWISTS AND TURNS OF THE URUBAMBA

The film’s budget was not very high, amounting to only $370,000. Given that one-third of that sum went into Kinski’s pocket and the film was shot in South America, creating significant logistical challenges, the amount was not particularly generous. Herzog knew he had to save money and couldn’t afford Hollywood-style extravagances. One way to cut costs was by filming with a single camera, which had “accidentally gone missing” from a display case at the Munich Film School. Part of the funding came from the earnings of Herzog’s previous films, while another portion was a loan from Herzog’s brother. A substantial financial boost also came from the German TV station Hessischer Rundfunk, which secured and utilized the right to broadcast Aguirre, the Wrath of God simultaneously with its theatrical release.

The modest budget necessitated careful planning. Herzog began his Aguirre, the Wrath of God adventure with a solo reconnaissance mission along the Urubamba, Huallaga, and Nanay rivers. Testing the waters on rafts, he assessed whether certain sections of the rivers would be too dangerous for the crew. During one of these tests, his raft split in two. Part of the wood was immediately sucked into a whirlpool, while Herzog reached the shore on the remaining half, carried a few kilometers downstream by the current. These meticulous preparations certainly helped avoid some unpleasant surprises, though that didn’t mean everything on set went according to plan.

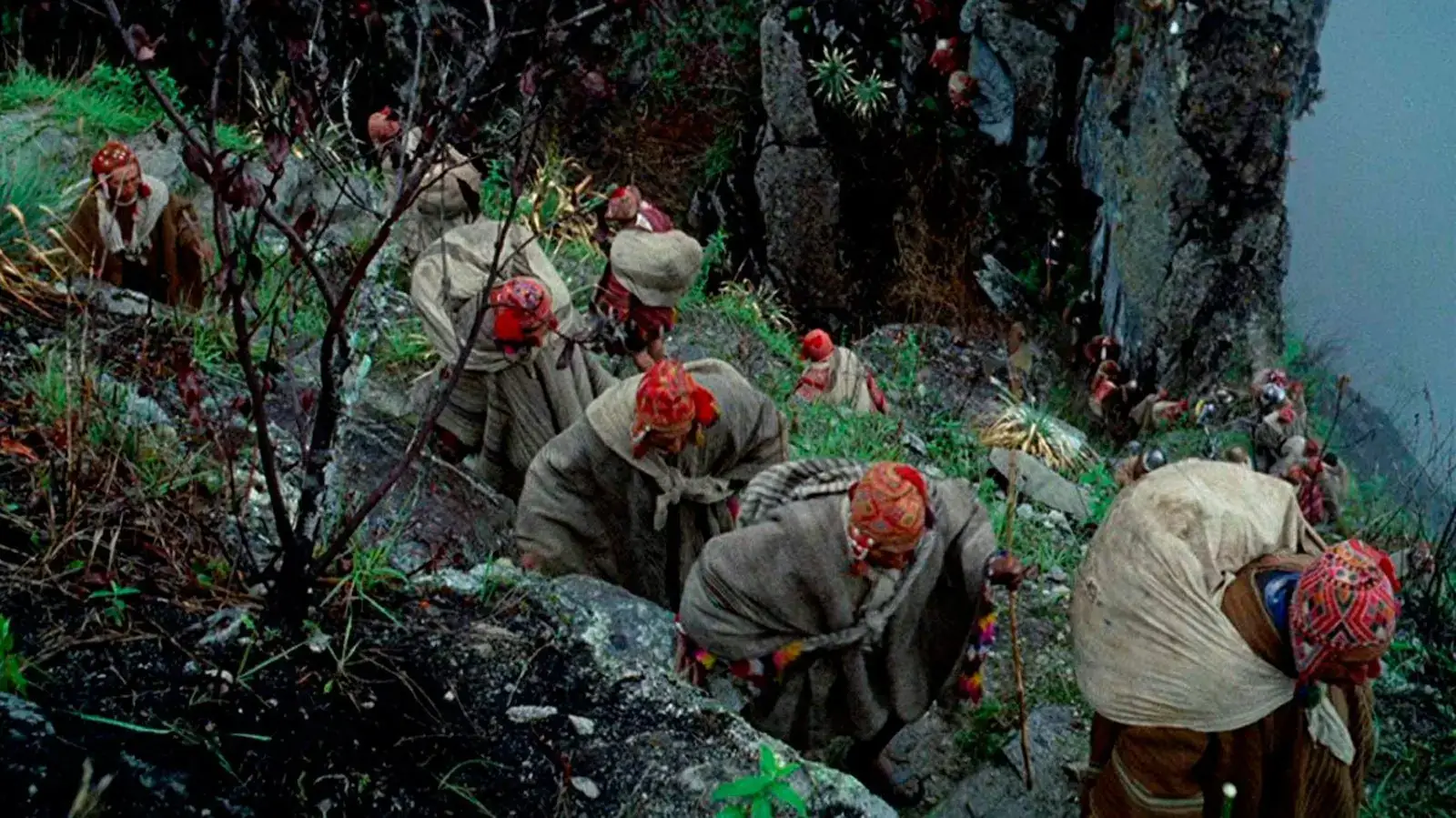

During the preparation phase, Herzog stayed in a hut owned by a local Peruvian woman, who kept about a hundred and forty guinea pigs (a traditional delicacy in Peru, known since pre-Incan times). Herzog recalls that nights spent among these curious animals were far from pleasant. The first proper camp was set up on the banks of the Urubamba River. Built on mobile rafts, it housed the crew and local extras (more than four hundred Indians from the higher Andes). When relocating between rivers (specifically, the Huallaga), the camp was destroyed. A much smaller team continued on. It took a week to transport all the equipment, people, and supplies 1,600 kilometers to the Rio Nanay (the entire shooting period lasted six weeks). From that point on, life continued only on the rafts built by the Indians. Setting foot on dry land was impossible because the jungle was flooded several kilometers inland.

Some scenes were written by nature itself. A prime example is the one where the raft full of conquistadors helplessly spins in a coastal whirlpool. During filming, the raft genuinely fell victim to the whirlpool, spinning in circles for several days before eventually breaking up on sharp rocks. Similarly, the sequence where some of the rafts are sunk and the Spaniards and Indians build new platforms was based on reality. A sudden rise in the river level submerged the previously constructed rafts, forcing the crew to stay put and rebuild their “wooden fleet.”

The intensity of the film’s final scene was also partly accidental. Herzog recalls that the monkeys swarming around Aguirre went into a frenzy, biting and attacking crew members (including the director, who kept quiet despite being bitten—he was, after all, shooting the take). Their appearance on set was also somewhat lucky. Herzog had paid for them earlier in the shoot, but their owner—taking advantage of the crew’s distraction—resold them to a wealthy American businessman. The monkeys were already in crates on a plane bound for the U.S. Herzog and his team went to the airport and, pretending to be veterinarians, demanded that the flight crew show them the vaccination certificates required for exporting animals out of the country. Since the documents were missing, the monkeys were released and promptly reclaimed by the filmmakers.

Klaus Kinski

Originally, the film’s prologue was intended to look completely different. Herzog wanted to start filming on a glacier located over 5,000 meters above sea level. However, he abandoned the idea because the altitude seriously affected many crew members. The prologue was ultimately filmed on the steep slopes of Huayna Picchu (2,720 meters above sea level), a peak that you can see in the background of every photograph of the famous Incan site, Machu Picchu.

Before departing for the shoot, Kinski was aware that Herzog had given up on the high-altitude scenes. Nevertheless, this didn’t stop him from bringing a large amount of mountaineering equipment. Herzog recalls that, along with Kinski, the camp was filled with “half a ton” of ice axes, crampons, ropes, carabiners, and harnesses. Kinski declared that he wanted to face the wilderness head-on. However, his willingness to confront the elements was quite selective. His vision of the jungle had no room for mosquitoes or rain. Even a single mosquito could trigger a panic attack that would end with him demanding anti-malaria injections for hours. The rain bothered him in a similar way. Despite the fact that an additional roof made of large leaves was constructed above his shelter, Kinski quickly concluded that there was no suitable place for him in the thickets surrounding Machu Picchu. After less than a day of “fighting with the wilderness,” he was already sleeping in a hotel room (at that time, there was a small guesthouse with eight rooms nearby).

As the crew moved down the river, Kinski became increasingly unbearable. He complained about the food, refused to drink boiled water (insisting on only mineral water), and constantly insulted the crew members. He derisively called Herzog a “director of dwarfs” because he had watched Herzog’s second feature film, Even Dwarfs Started Small, before arriving in Peru. But that was not the most dangerous aspect of Kinski’s behavior.

Just before the filming of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Kinski had performed a series of monologues titled Jesus Christ Savior. When he arrived on set, he still hadn’t entirely left his previous role. In the Peruvian jungle, he continued to portray himself as an emotionally unstable and misunderstood Jesus. Herzog mentioned that throughout his life, Kinski sometimes became so immersed in his roles that he couldn’t free himself from them for months. In addition to Jesus, he was also overtaken by characters like François Villon, Prince Myshkin from Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, and later in life, Paganini. In the Amazon jungle, Jesus met God’s Wrath in the form of Lope de Aguirre.

This blend of roles led Kinski to lose touch with reality and give in to his emotions even more easily than usual. During a scene where the conquistadors arrive on the shore and begin to destroy a native village, some of the starving characters start grabbing bunches of bananas. Aguirre decides to drive them away from the fruit. We see Kinski running in the background, his face contorted with rage and madness. Moments later, he raises his sword and strikes another actor on the head. The blow is so forceful that only the actor’s steel helmet prevents him from being killed. The blood seen in this scene is real. The injured man spent nearly three months in the hospital. On another occasion, forty-five extras gathered in a shed to play cards and drink. Kinski didn’t like the idea. He ran out of his hut with a Winchester rifle he had brought from home and fired four shots at the wooden building full of people. One of the bullets shot off the tip of an extra’s finger, which, considering the crowd in the shed, was a fortunate outcome.

During the last week of filming, Kinski completely ignored Herzog’s directions and couldn’t remember even a single line of dialogue. He vented his frustrations on the crew. When Herzog informed him that he wouldn’t fire the sound technician whom Kinski had just insulted, Kinski threatened to board a boat and leave the set immediately. Herzog took him aside and said he had a gun and nine bullets in his tent. Kinski was shocked as Herzog calmly told him that if he truly decided to leave the set, then at the next bend of the river, he’d have eight bullets in him, with the ninth reserved for Herzog himself. Thus, the legend of Herzog threatening to shoot people on set was born (Herzog also admitted that he once thought about blowing Kinski up). The threat worked; Kinski stayed on the set and behaved exceptionally calmly for the final week of filming.

Years later, Herzog admitted that during the making of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, there were only two problems: the budget and Klaus Kinski. Even the native extras who returned to film Fitzcarraldo (Herzog’s later film shot in the same locations) seriously suggested to Herzog that they could “take care” of the mad Aguirre for good. Herzog declined, though the offer was quite tempting.

Into the Mouth of Madness

Aguirre, the Wrath of God is often categorized as a historical drama. A few real names, a title card before the first scene, and a series of references to events recorded in chronicles—this seems to suffice for many viewers to see Herzog’s film solely as a story about the Spanish conquest. However, Aguirre, the Wrath of God doesn’t strive for historical accuracy. In interviews, Herzog either cannot or does not want to specify the sources he used while writing the script, openly admitting that he treated history merely as a source of inspiration. Therefore, Aguirre, the Wrath of God is not a historical drama but a drama of the human mind.

The film’s unforgettable prologue (one of the most hypnotic and unsettling scenes in the history of cinema) signals this from the start, with a line of faceless individuals moving through the mist over Huayna Picchu. Amid the vastness of nature, humanity appears so small and lost. For the Andean slopes and fog, it doesn’t matter if it’s Pizarro, Aguirre, or Ursúa in the procession—they are insignificant against the tangled web of rocks and trees. Popol Vuh’s eerie music enhances the surreal feeling of descending into the jungle, which for Herzog is a reservoir of “our deepest desires, emotions, and nightmares.” For the German director, the setting is never just a background. Both the act of descending into the jungle and the jungle itself are meaningful. Is there awareness at the peak, and only madness downriver? We don’t know, as we’ve never seen either the peak or the river’s mouth.

The film’s composition and rhythm continuously emphasize not only Aguirre’s inner journey but also that of his entire crew. In the early stages of the film, we can clearly distinguish what is real from what is mere illusion. The jungle seems unsettling, but in a natural way—a primal fear of nature’s vastness. Once Aguirre seizes power, everything changes. Reality begins to crumble like a house of cards. Popol Vuh’s music suggests that nothing is what it seems, the action nearly halts, and time loses its meaning. The rafts with the conquistadors drift into an unfamiliar space that no longer resembles the initial jungle. In this reality, even the birdsong sounds eerie, signaling the presence of something unspeakable.

Herzog highlights the nature of this place at every step. Among the treetops, there are ships (the crew built ship fragments on the ground and then hoisted them into the trees!), arrow wounds stop bleeding, people vanish into the jungle never to return (Inez even dons a festive dress for the occasion), and actors look into the camera with terror. It all circles around the heart of darkness, which, like El Dorado, exists only “in the mind” of man.

Initially, Herzog wanted to end Aguirre, the Wrath of God with a scene in which the raft carrying the conquistador reaches the river’s mouth and sails into the Atlantic. A parrot on board was to cry out, El Dorado! El Dorado! Such an ending would have been too simple, a kind of escape from this strange place. The final scene, with Aguirre (the last survivor of the expedition) still heading toward the unknown, is far more powerful. There is no escape from the demons of one’s mind. For Aguirre, the search for El Dorado will never end.