M Explained: Fritz Lang’s Shockingly Relevant Masterpiece

The Enduring Relevance of M

The question of “crime and punishment” still hovers over the gray streets of an unnamed German city. And most importantly, for understanding the phenomenon of M: the question posed by Lang nearly eighty years ago—long before the demons of World War I and World War II—remains just as relevant in our era of globalization and commercialization. Lang delicately captured nearly all the “for” and “against” arguments raised by modern abolitionists and retentionists. In the following paragraphs, I will not claim the right to make a definitive judgment on the described situations. Instead of offering a final verdict, I will pose rhetorical questions.

Let us begin by analyzing the character of the serial killer, likely also a rapist and pedophile (stating this explicitly would not be in the style of the German director), since the potential death penalty would concern him—Hans Beckert. Lang from the beginning portrays him as a calm fellow who is perpetually amazed by the world around him, with unrealistically large and deep eyes. The problem begins when a characteristic whistle starts coming out of Hans’s thin lips (imitating the tune of In the Hall of the Mountain King, composed by Edvard Grieg for Ibsen’s drama Peer Gynt). The melody, which accompanied Ibsen’s hero as he fled from hostile mountain creatures, signals the worst in M—the awakening of Hans’s evil nature, a murderer who takes pleasure in killing innocent, naive children. In the murderer’s eyes, we see helplessness and panic on a platter. The best illustration of this is the scene where Hans walks down the street, whistling the tune. Suddenly, he speeds up and, like a madman, runs into the nearest bar/restaurant with no idea what to order. Finally, after a series of nervous changes in decision about what he wants, he orders a shot of something stronger. The melody gets faster—he tries to drown it out, he tries to fight it, but as we know, it’s all in vain (the “other” is stronger).

The hyperbole of this already expressive fragment comes in the next two scenes: the chase in the abandoned building and the trial of Hans by local criminals and the victims’ families. The first scene perfectly illustrates the fear that accompanies the life of a murderer, the fear of being exposed, completely contrary to the psychological profiles of serial killers. We can understand that this man is not another emotionless deviant who doesn’t comprehend the seriousness of his actions. The next scene tells us even more about him. During his crimes, Hans falls into a frenzy, causing him to forget the crime afterward. He learns about the horrifying nature of his outings from newspaper headlines and posters offering a reward for his head. As if that weren’t enough, he falls to his knees and sincerely (it’s obvious) expresses his internal tragedy, his inability to control his sick urges. “You don’t know what it’s like,” he says, and he’s probably right, we don’t.

In summary, Hans is a normal man in his day-to-day life, keeping away from high society and crowded cafes. He doesn’t stand out, doesn’t seek cheap thrills, and avoids trouble. Against his will, something sometimes awakens in him (let’s call it using religious terminology) a “demon” commanding him to kidnap and murder children. He first pampers them with sweets, balloons, and toys, taking advantage of their trust and naivety to fulfill his wild desires. However, he doesn’t remember the act of killing itself. It seems that his memory is wiped clean from the moment he starts whistling to the moment he falls asleep after the act of aggression. After returning to his “normal” state—the state before falling into one of those murderous frenzies—Hans sincerely regrets his actions and is terrified at the mere thought that soon Grieg’s notes will once again escape his lips. Do we have the right to judge Jekyll for Hyde’s bloody escapades, especially considering that Hans did not experiment with drugs to create his own Hyde?

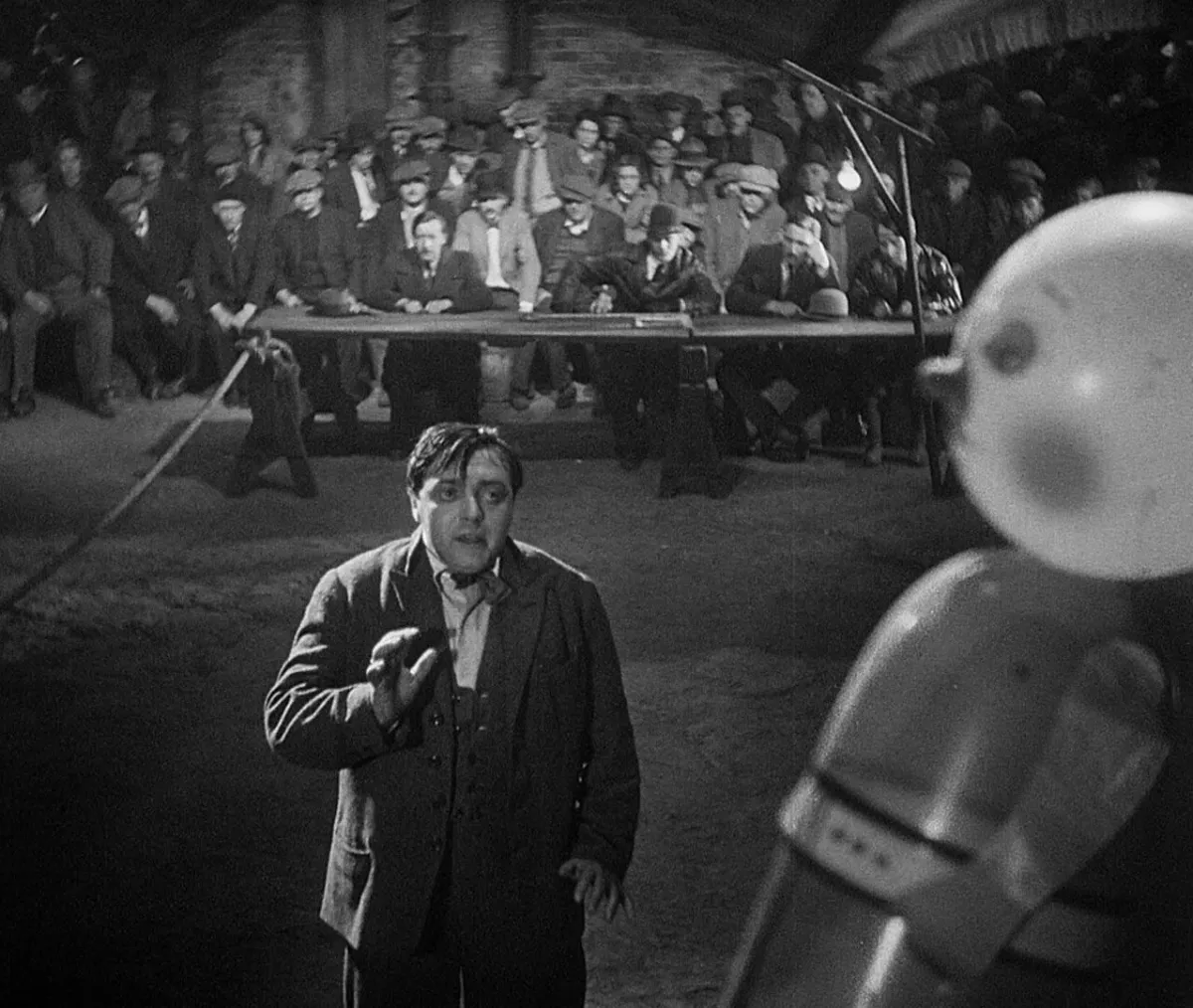

The last sentence of the previous paragraph raises a question of enormous importance in the debate between abolitionists and retentionists—“Do we have the right to judge?” Lang’s film asks it masterfully—there’s no other word for it. In this respect, M is simply a masterpiece. We need only focus on the social trial scene, which takes place in a dark, dirty, forgotten basement, the kind found in every major city. We’ve already mentioned Hans’s “confession,” made during this segment of Lang’s film. But we must also note that sitting in judgment over the murderer are people who have themselves killed or sinned multiple times. People devoid of judicial office—unquestionable criminals, shady characters, but also mothers of murdered children staring at their tormentor in pain. The questions Lang asks directly pierce through the dust-laden basement air of this unusual courtroom. Can a person claim the right to decide the life of another when they themselves are not perfect, and perfect people do not exist and never will? And perhaps more importantly, is the very institution of court sometimes an illusion that allows us to silence our conscience? Let’s note that no lynching—no bloody mob justice—took place. Instead, a makeshift trial was organized with remarkable speed. Why, when the outcome was clear from the beginning? After all, one of the first lines in the trial was: “We do not intend to keep you in prison on our hard-earned money.”

The scene that sums up M, and in my view is key to understanding Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou’s position, is the brief snippet of the official trial, or rather, the reaction of one of the mothers after hearing the sentence, which we viewers can only speculate about. The tearful woman, clothed in mourning, says (as if to herself) that what happened just moments ago in the massive courtroom, carved from some noble wood, will not bring her children back. What was the point of it all?

The suggestiveness of this scene makes me believe that Hans received a death sentence, postponed by the police’s intervention during the basement trial. And it seems that Lang put his own feelings about the death penalty into the grieving mother’s mouth. Why, since we cannot restore life, should we take another? On the other hand, can the life of a murderer balance the scales if, on the other side, lies the life of his innocent victim? Lang’s ambivalence may also explain his repeated claims that real events (especially Kürten’s case) did not influence the story presented in M. While Hans Beckert may evoke sympathy from the audience, a ruthless murderer, rapist, and deviant drinking the blood of his victims could not gain any public sympathy. Perhaps Lang simply did not want society to think that their great director was defending someone like Kürten?

M and Formal Revolution

Playing with Expressionist Fetishes…

…and particularly the recurring motif of the shadow as an almost autonomous entity. While in early expressionist films based on Caligarist aesthetics, the shadow detached from what cast it, occupying large canvases crowded into cramped film studios, in the later phase of the movement (mainly thanks to Murnau and Lang himself), it was given life. Recall the vampire creeping toward his victim and the perspective from which this approach was filmed. In the early stages of the shot, we do not see the character (which, for those times, was unusual), but rather a well-lit wall where the huge shadow of the night visitor appears. The black blot cast by him on the wall becomes more terrifying for a moment than he himself. Similar techniques can be seen in other Murnau films, like Faust, and in Lang’s works (for instance, Destiny or Metropolis—a sort of city of shadows). In M, the shadow gains another property—it starts to speak. At one point, it replaces the protagonist (in the scene where Hans’s face casts a shadow on a wanted poster). Thus, the shadow becomes an autonomous entity—something it had aspired to throughout the movement’s existence.

Revaluations…

…the most important of which is the previously mentioned revaluation of the dichotomous model of the world, proposed by expressionist cinema for almost its entire duration. In M, we do not have good people and bad people. Those dressed in white in bright rooms, and those dressed in black rags, huddled in equally black dwellings. In Lang’s world, everyone seems equal—a bit bad and black, and a bit good and white. The director looks at the world from a completely different perspective than the one that prevailed just a few years earlier.

The same can be said about the figure of the murderer himself. Peter Lorre’s appearance—those teary eyes and remorse for his sins—would make him a positive character in most expressionist films. Lang avoids painting another madman with corpse-like skin and black eyes contrasting with unnatural skin brightness, a madman laughing maniacally at his actions, plotting great crimes against humanity. Finally, he also strips the character of fantastic dimensions. Hans cannot be seen as a legendary hero—a symbol drawn from folklore. He is a flesh-and-blood human being, as the film’s working title says—“someone who lives among us.”

Masterful Sound Design…

…despite M being Lang’s first sound film. While most sound films produced shortly after the invention of sound used music and voices to crudely illustrate events on the silver screen, Lang immediately reached the level of today’s productions. He instantly understood that sound could not be just an addition—it could become an equal element of the film, influencing its reception as much as the image.

To illustrate what I mean, a few short scenes suffice. The first takes place in Elsie’s house—the girl abducted by Hans. We see her mother preparing a meal. Suddenly, the clock strikes the hour, and the bells chime—the mother smiles, knowing her daughter has just finished school. Unfortunately, her return is delayed. The mother begins to worry, and the sounds fade and fade until we hear nothing. Then the mother rushes to the window, calling her daughter loudly and with growing distress. Lang shows us the empty staircase, the empty attic, and the empty meadow. When the action moves outdoors, her shouts fade. In complete silence, we watch the balloon Hans bought for Elsie get caught on power lines…

The second scene connects two distant places. Visually, we are in Hans’s house, but the sounds come from the police station. A policeman provides a psychological profile of the murderer, emphasizing that he is surely an ordinary citizen. Hans watches himself in the mirror with horror, nervously touching his face as if he hears the officer describing him.

Throughout the film, Lang frequently contrasts scenes full of noise (street hustle and bustle) with completely silent ones. He understands that silence can sometimes say much more than noise. Finally, we must mention how the beggars expose the murderer—the blind man recognizes the melody Hans whistles while buying a balloon for Elsie. Sight failed, but sound solved the case—a symbolic nod from the old medium to its modified version.

A Few Words in Conclusion

Despite the passage of time, M has not lost any of its value, let alone its relevance. Just consider the emotions sparked by films addressing the death penalty, such as The Green Mile, Dancer in the Dark, or Dead Man Walking. Look at how much controversy arose around the execution of Saddam Hussein, an undoubtedly guilty criminal. Examples are not hard to find. Consider the case of the W. brothers, responsible for lynching a recidivist who endangered the lives of villagers. According to the letter of the law, they should be convicted of premeditated murder, but the people see them as local heroes. The same issues arose in M—does the life of a criminal equal the life of his victims? Is the judgment of those wronged more natural than the judgment of bureaucrats? And why should we pay money to keep a repeat offender in prison (if the brothers had not taken matters into their own hands)?

The topicality of the themes matches the relevance of the form. I dare say that if someone were to show M to an audience unfamiliar with its existence and claim it was an independent film made in contemporary times, many people would buy that story. There’s no theatrical acting typical of silent films, the relationship between sound and image is as we know it from today’s films, and the topic remains relevant and emotionally charged—what more could you want?