FARGO. Film Noir Upside Down: Coens’ Masterpiece Explained

And indeed! The brothers mock the audience when, at the very beginning of this theater of the absurd, they serve us this information: The film depicts true events that took place in Minnesota in 1987. At the request of the survivors, the names have been changed. Out of respect for the dead, the rest has been portrayed exactly as it occurred.

Why did the Coens play such a cruel joke on us? Perhaps they did it for fun, which ended tragically (how fitting to their style!). Maybe they wanted to convey that it’s not the Coen brothers who write such twisted stories, but life itself. Either way, if the viewer patiently watches until the end credits of Fargo, they will realize they’ve been fooled when they read that the characters in the film are fictional and any resemblance to real people is purely coincidental.

A Plot Straight Out Of A Noir Crime

The film tells the story of Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy) – a car dealer who, due to his unfulfilled ambitions, unwittingly initiates a chain of events that lead to the deaths of seven people.

Jerry has a business idea. All he needs is a significant capital, which his wealthy father-in-law (who considers him a life failure and a poor match for his daughter) refuses to provide. Jerry takes his fate into his own hands and hires two thugs (Steve Buscemi, Peter Stormare), who are tasked with kidnapping Jerry’s wife (Kristin Rudrud). Lundegaard is to receive half of the ransom paid by his father-in-law (Harve Presnell). The job is supposed to be clean, without any violence and consequently, no victims. However, the whole deal changes dramatically when the mastermind receives a call from one of the kidnappers: There’s been blood, Jerry – he hears through the receiver.

Everything begins when the gangsters are stopped by the police for a trivial reason. When the officer refuses to accept a bribe, one of the kidnappers – Gaear – pulls out a gun and shoots him in the head. They can’t risk a search – they have Jerry’s kidnapped wife in the back seat. Here, for the first time in Fargo, we can admire the Coens’ mastery in using blind chance. A car with a terrified driver and a young girl approaches from the opposite direction. After a short chase, the inconvenient witnesses are eliminated. Thus, within a few minutes, the “clean job” turns into a bloody massacre with three innocent victims. The mysterious murders are investigated by Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) – a kind and somewhat naive police officer in advanced pregnancy, who approaches her work with clear detachment.

Film Blanc

Fargo, as a work falling under the postmodernist system of signification, plays with the conventions of crime genres. The world presented – as is typical for the Coen brothers – is turned upside down and seems to defy all principles of the crime scheme. After watching Fargo, I noticed something that might not have been a deliberate effort by the creators, and if it wasn’t, it makes it all the more intriguing and noteworthy. I’m thinking of the construction of the presented world, which appears to be the complete opposite of the diegesis in noir films. Why such a judgment?

In a noir film, the world is twisted, exuding darkness and infecting the characters who inhabit it. It’s the world and environment that influence the characters, not the other way around. Noir films are full of gangsters, thugs, prostitutes, and corrupt cops. Practically no one acts morally; everyone is infected by the rot of their surroundings to some extent. Everyone has dirty hands, which is a necessary consequence of living in this flawed world. However, every fan of Chandler’s prose knows that detective Philip Marlowe is fundamentally a good person, defending himself against the rot with all his might (his weapon is sarcasm). The setting is always a big city – steeped in semi-darkness and full of suspicious nooks.

With the Coen brothers, values are reversed. The world is good and harmonious, untouched by evil – in a sense, “virginal.”

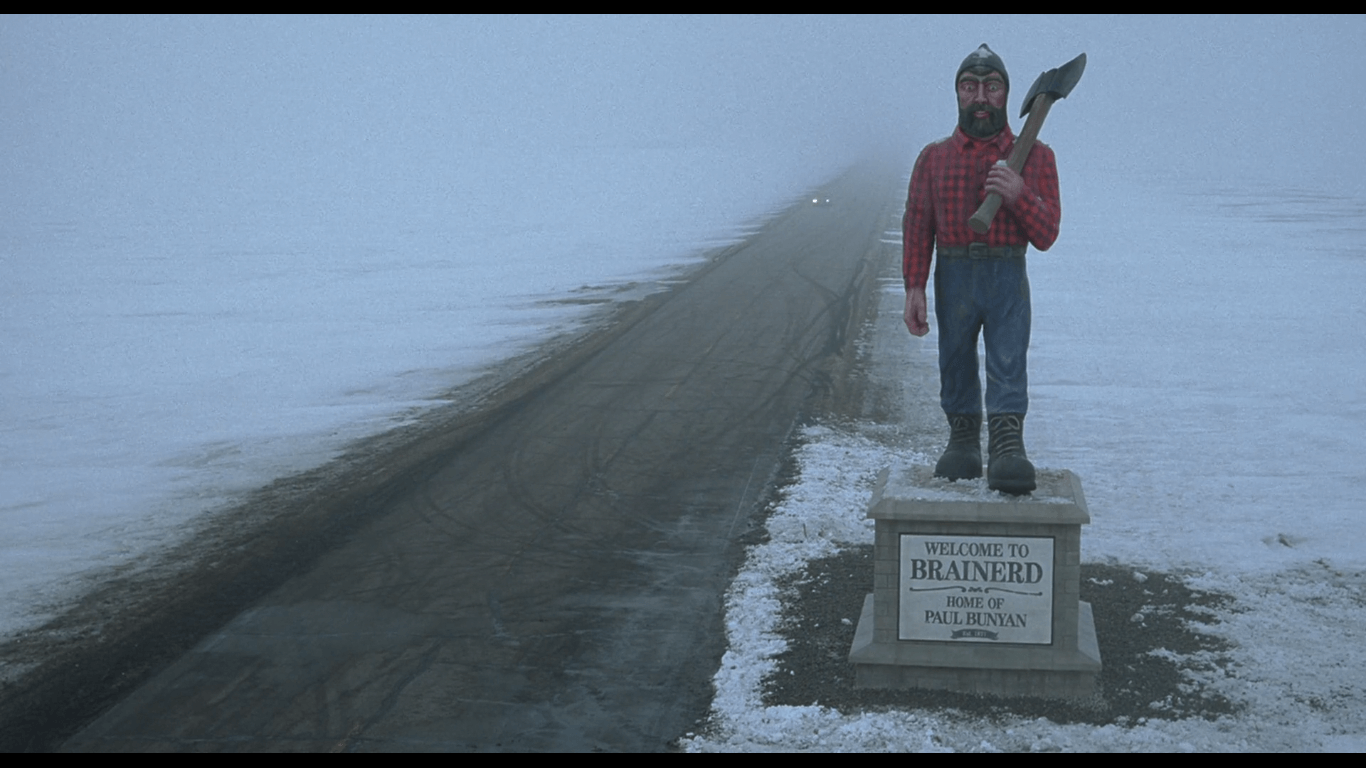

Let’s look at the town of Brainerd, where the murders occur. Its residents are kind and straightforward people for whom crime and cruelty are anomalies. These are so foreign that they can’t even describe what the wanted criminals look like. The only description that comes to their minds is “funny.” What does ‘funny’ mean?– the officers ask. How do I know? Just funny. In the general sense – one of the interviewed prostitutes says, and later the bar owner. The sleepy town has a friendly atmosphere, everyone knows everyone, and they are painfully polite to each other. The specific accent used only by positive characters adds to Brainerd’s and Minnesota’s overall cozy climate (the brothers are known for exaggerating various accents in their films). The annoying “yaaa?”, “oh, yaaa” follows us throughout the film, endearing us and deepening our connection with the residents.

Everyone seems content and happy (the wide, almost unnatural smiles that never leave the faces of Brainerd’s kind folk are telling), living peacefully where the devil says goodnight and minding their own business. An interesting character in the film is Marge Gunderson, flawlessly portrayed by Frances McDormand. In the middle of the night, the police officer receives a report of a triple murder. She drags herself out of bed, as her caring husband – looking like a true homebody – declares that he won’t let her go without breakfast. Their cozy nest exudes warmth and tenderness and thus could serve as a metonymy for the entire Brainerd and the world created by the Coen brothers in general. Marge and her partner at the crime scene seem to not fully grasp what they’re doing, as if the brutal murder is new to them. They chat about everyday matters as if they don’t fully understand the gravity of the situation.

Just as in noir films some characters in the corrupted world carry the seed of goodness, so in the Coen brothers’ film, in the pure environment of this “white” world, there are individuals who seek to disrupt its harmony. As mentioned – values are reversed. In Fargo, individuals influence the environment (unlike in noir cinema). What are the brothers trying to say with this? Perhaps it means that, in their view, humans are inherently pure, and evil is an artificial and foreign creation. This would contradict the views of noir crime and film noir authors, who present evil as an integral part of the human soul – spreading like a disease. In the Coen brothers’ film, the characters marked by the stain of sin and anomalies are essentially only four people: Jerry Lundegaard, Shep Proudfoot, and the two kidnappers who mercilessly disturb the peace of the town’s residents. The first character is fundamentally different from the rest – cold and ruthless criminals. After all, Jerry Lundegaard initially evokes our sympathy and even compassion. He is a person like any of us – he wants to finally succeed but lacks the opportunity.

So why do I list this character alongside the three bandits? The recipe for life according to the Coen brothers seems very simple and can be summarized in short slogans: “Don’t stick your neck out,” “Be content with what you have,” “Learn to take joy in the little things.”

Of course, all the other characters are just ordinary people! They don’t stand out with any particular traits and are simply going about their own business. They are anonymous, but because of this, they are happy. Just mention the friendly police officers at the station, the “warm noodle” – Marge’s husband, the killed officer who didn’t take a bribe and whose only notable trait is that “he looks like a nice guy.”

There are more of these ordinary folks – the innocent parking attendant, the silly yet friendly prostitutes (who are far from noir’s femmes fatales), the random witnesses of the road murder, Jerry’s wife around whom the whole plot revolves but about whom we know almost nothing, and finally the child (the embodiment of innocence!) – Jerry’s son, who in one scene listens to a lecture about his mediocre grades. Also noteworthy is the dialogue between Marge and her husband in the last scene, where the loving wife rejoices over her husband’s small success.

Hilarious and suggestive is also the scene where one of the kidnappers tries to leave the parking lot without paying and, arguing with the guy in the booth, gives us the definition of a content, Coen-esque average Joe: You must think you’re a big shot in that dumb uniform. Office tie, important figure. This is your whole world. You’re the king of this gate. Here’s your lousy 4 dollars. Ambition, then, seems to be the gravest sin according to the Coen brothers. That’s why the clumsy Jerry is as much a villain in the film as the bandits who pull the trigger without hesitation. He committed the sin of ambition and is condemned by the Coen brothers.

Let’s stick with the characters for a moment. They all seem to have been created by simply reversing the traits from noir films. The criminals, for instance, are not serious and lack a professional approach to their task. They bungle literally at every step. Before the action, they stop at a motel and order girls, then call their contact who’s out on parole. Later, in broad daylight, they break into the victim’s house with a crowbar (making a lot of noise, and it’s the victim who notices them first, thus ruining the element of surprise that professionals from noir films would certainly have maintained). In the same scene, one of the thugs gets bitten by Mrs. Lundegaard, who, with a terrified scream, breaks free and runs upstairs. The kidnapper (right in the middle of the action!) looks blankly at the wound and says: Ointment. I need ointment – then starts looking for it. Carl forgets to put the temporary plates on the car, and thus the kidnappers get stopped by someone who wouldn’t exist in a noir film – a cop who doesn’t take a bribe. Not only are the gangsters’ behaviors in Fargo grotesque, but – as I mentioned earlier – the police methods also leave much to be desired. Just think of Marge’s partner, who serves as a coffee holder while investigating the crime scene, or Marge herself, who doesn’t see anything suspicious in Lundegaard’s nervous behavior during questioning. Examples abound.

Just like in a noir film, the setting here is extremely important – in Fargo, we move to the wilderness, a place where a person finds peace untroubled by the noise of the asphalt jungle.

An important element in the creators of Barton Fink’s film is the symbolism of white – omnipresent and filling almost every frame of Fargo (standing in opposition to the ubiquitous black of noir). Let’s look at the cinematic landscapes. The action takes place in the open spaces of Minnesota – vast and snowy. The white that dominates the screen reflects all the characteristics of the world outlined by the Coen brothers – innocence, purity, goodness, honesty, etc. Symbolic, for example, is the bird’s-eye shot of a lone Jerry against the backdrop of a white desert. This shot perfectly illustrates the relationship between the world and the character I talked about earlier. Lundegaard looks like a dark spot contrasting with the snowy whiteness of the frame – Jerry clearly doesn’t fit, he’s a foreign element disrupting the harmony of the scene. Another interesting shot with a similar meaning is the close-up of a bag of worms held by Norm – Marge’s husband. At the moment of the close-up, we hear Frances McDormand’s voice-over – Looks pretty good. She obviously means the sandwiches brought by her husband. However, the shot is telling. It’s as if the Coen brothers are saying: This perfect world looks good, but under the surface, disgusting vermin lurk.

Another important element capturing the film’s atmosphere is the music, sometimes sad and melancholic, other times calm and idyllic – contrasting with the dramatic events of many scenes. We hear it during the attack at Jerry’s house, during the burial of the money suitcase, and in other such situations. This choice of music might aim to ridicule the actions of the “bad” characters. This contrast shows how pointless and pathetic their efforts are since the brothers know from the start that ultimately, good and justice will triumph in their film. Evil is only a temporary pathology that fades as quickly as it appears.

There was Mrs. Lundegaard on the floor. And that guy in the wood chipper was your accomplice? Plus the three others in Brainerd. For what? For a little bit of money. There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’t you know that? And here you are, and it’s a beautiful day. I just don’t understand it. These words of Marge Gunderson, spoken in the police car to one of the kidnappers, are the best conclusion to Fargo. They reflect the naive way of thinking of the good-hearted inhabitants of Minnesota and their lack of understanding of the cruelty that shakes their orderly and stable world. The white world of this unique film blanc – if I may coin a neologism.

Grotesque Realism of Fargo

It’s hard to say whether the reversed noir convention brings us closer to realism. Could the events depicted in Fargo really take place, as suggested by the opening credits? The Coen brothers’ characters paradoxically seem more human than the characters in noir films (despite this realistic scheme being reversed by 180 degrees). The detective role is filled by a pregnant woman instead of a handsome man in a trench coat, the bandit is a guy who “looks funny,” and the mastermind behind the whole operation, which goes out of control in the first scenes of the film, is Jerry – financially dependent on his father-in-law, who in no way resembles the criminal masterminds from crime novels.

So, do we “buy” the story in Fargo as the creators intend, or do we think it’s too absurd to be true? The brothers seem to claim that the more grotesque and incredible the story, the truer it is.

Did the experiment succeed?

Words: Milosz Drewniak