DOUBLE TAKE Deciphered. Did Alfred Hitchcock Have a Double?

They say, that if you meet your double,

you should kill him, or that he will kill you (…)

The two of you is one to many.

By the end of the script one of you must die.

Did Alfred Hitchcock have a double? Did a sinister shadow follow the director? Did he come face to face with his doppelganger and decide to follow the age-old principle: If you meet your double, you should kill him, or he will kill you. Two of you are one too many? Double Take it is.

Four years before the biographical film Hitchcock directed by Sacha Gervasi hit theaters, and before Anthony Hopkins took on the role of the master of screen horror, a much less known film was made, where the great director, who had been dead for nearly three decades, returns and speaks to the audience post-mortem. This film is *Double Take* by Johan Grimonprez. But this full-length pseudo-documentary film has its more modest twin brother.

In 2005, Johan Grimonprez—a Belgian filmmaker with artistic ambitions—was preparing to work on the film Double Take. He organized a casting for a double of the famous director Alfred Hitchcock. At the audition, several men of different ages appeared, believing that they bore a striking resemblance to the master of cinematic suspense. Among the potential Hitchcock doubles was the now-deceased Ron Burrage. The preparations for the film led to a sort of epilogue of Double Take, a video installation titled Looking For Alfred. Double Take is an extension of Grimonprez’s search and an extraordinary film collage oscillating around seemingly unrelated themes such as: the sinister double, the specter of death, original and copy, the Cold War, nuclear tests, communism, television, the role of the media, the American industry, the beginning of the post-war era of consumerism, filmmaking, etc.

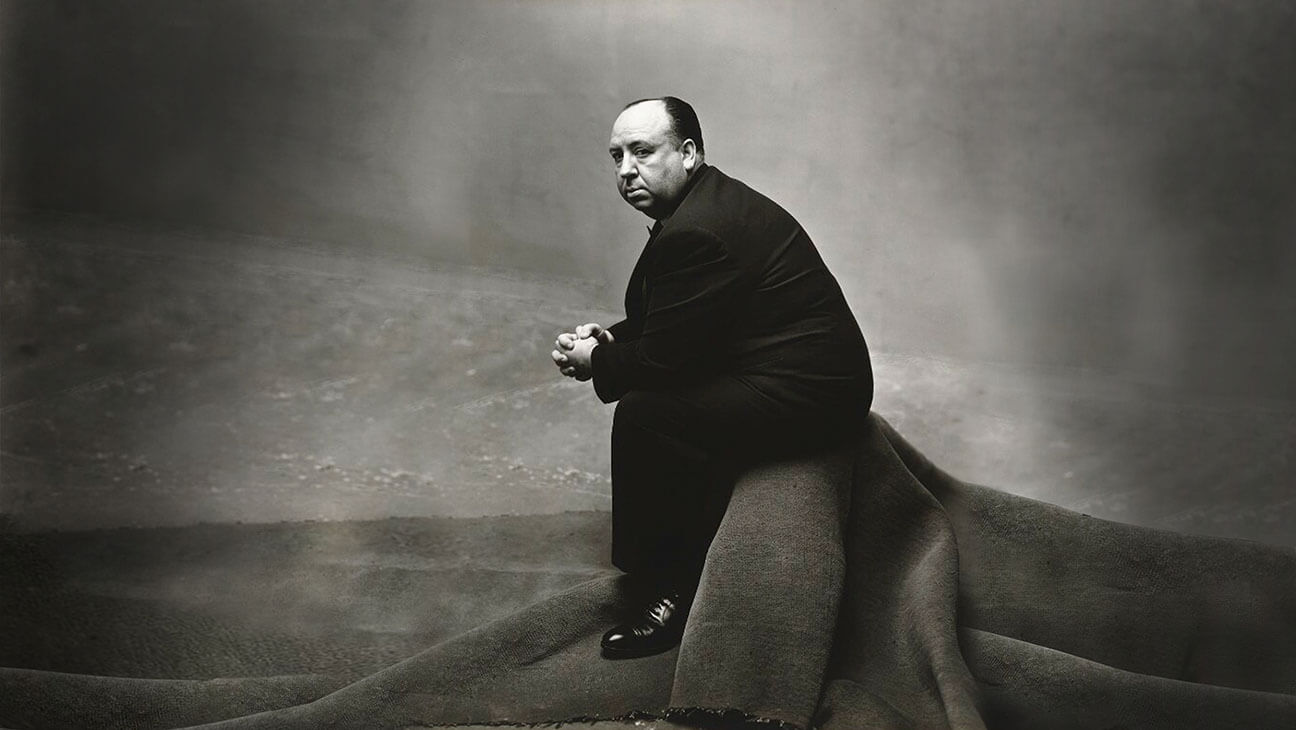

Double Take hit the cinema screens in 2009. It was recognized at the Berlinale and Sundance festivals, as well as at Poland’s New Horizons. It was presented at the prestigious Museum Of Modern Art in New York and is part of the permanent exhibitions at the Tate Modern in London and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. What is so extraordinary about the Belgian director’s film? Everything. The subject matter and form. The metaphors and the originality of the message. The references to literature and (pop) culture. And most of all, the central figure of this work, its main character, the returning-from-the-grave Sir Alfred Hitchcock.

The core of this cinematic story consists of excerpts from the prose of the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, whose obsession with doubles was reflected in, among others, his stories August 25, 1983 and The Other. In Grimonprez’s film, we encounter a paraphrase of Borges’ stories about encounters with the double. A doubly unusual encounter, as it is not with one’s ideal copy, but with a younger/older version of oneself. Just like in August 25, 1983, in the filmic story, Hitchcock meets his doppelganger in a hotel. This event is a combination of reality and fiction, probability, and fantastic eeriness. Grimonprez partly placed this encounter in the actual time and place where Hitchcock was staying at the time, while simultaneously giving it a universal, symbolic, mythical—one might say—character.

The year 1962, while working on the film The Birds, the director is asked to answer the phone. He opens a certain door and sees himself behind it… The encounter with the double takes place at the intersection of different dimensions. Perhaps in a film studio office, or maybe in a café. The location also resembles a hotel room and several other places familiar to the director. Just like in Borges’ story The Other, it’s impossible to establish the place and date of the meeting. It takes place outside of place and outside of time. Perhaps it is only a dream.

I immediately recognized the voice. The figure slowly turned toward me. ‘I was waiting for you,’ he said. And that’s exactly what I feared. The man I had been tricked into meeting by a false phone call resembled me in every way, except for one thing. He was—as the guard noted—older.

The contemporary Hitchcock double consists of two people (sic!). The first is the doppelganger with whom the director shares appearance, Ron Burrage; the second is the man speaking with the director’s voice, Mark Perry. It’s astonishing how well he imitates Hitchcock’s voice. The timbre, depth, and tempo of speaking—all match. But this wasn’t an innate talent; practice was required. One of the first scenes of Double Take documents such a rehearsal recording. Mark Perry, using Alfred Hitchcock’s voice, tells the famous joke about the nonexistent MacGuffin. Meanwhile, Ron Burrage, during the making of Double Take, was roughly the same age as Hitchcock was when he was working on The Birds. Burrage has Hitchcock’s height, build, baldness, and face. After Hitchcock’s death in 1980, Burrage often took on the role of the famous director at film events, imitated Hitchcock in commercials, and replaced the late director in the announcements of the Italian edition of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents program. Both Burrage and Perry play dual roles in Double Take, portraying both Hitchcock and themselves.

The eighty-minute film is mostly black and white due to the nature of the archival footage used, including clips from Hitchcock’s films and the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV series, 1960s television commercials, and contemporary propaganda films. The color fragments stand out and contrast sharply with the rest of the image. A characteristic feature of Grimonprez’s work is the blurring of the boundary between reality and cinematic creation. Sometimes it’s hard to tell whether the scenes visible on the screen and the off-screen comments are still source materials with the real, unique Hitchcock or the cinematic creation of his doubles, the Burrage & Perry duo…

Already during the film’s opening credits, we see pairs of twins. Old grainy photos and recordings. Two identical girls, two identical young men standing shoulder to shoulder and smiling at the camera. All these doubled figures have something demonic in them. Sinister looks, false smiles, behind which lies darkness and unspoken threat. This epilogue aptly captures the horror of meeting one’s double, which will soon befall the film’s Hitchcock.

There are many more obvious and less obvious references, symbols, and metaphors related to doubles in Double Take: the omnipresent quotes from the advertising campaign of Folgers Coffee, instant coffee—an imitation, a substitute for real coffee, a product that—as the manufacturer claims—tastes like freshly ground coffee, is “just like” the original but isn’t one; the director’s two identical terriers, which Hitchcock used to walk on a leash; August 13th, the birth date of both Alfred Hitchcock and his double Ron Burrage—an unmistakable sign of the double essence; a bowler hat rolling down corridors and stairs… Hitchcock didn’t often wear this headgear, but another great artist, Grimonprez’s fellow countryman, René Magritte, the surrealist painter who couldn’t get doubles and mirror reflections out of his head, never parted with it; Hitchcock himself played with the motif of the double, the split identity, the original and the copy, and identity itself in his films (in one episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, he appeared in several copies, and in another, in two slightly different incarnations); then there’s the film set as a replica of actually existing places, characteristic editing, repeatedly showing the same shots and scenes; finally, “le double,” the French term meaning “double” but also “ghost,” this second meaning directly refers to cinema as a reflection—the double—of reality (Double Take is, to some extent, also a meta-film, a work about how a film is made, about shooting, and sound design). Double Take also shows how the movie screen, smaller in size but multiplied in quantity, began to massively infiltrate the homes of ordinary citizens in the 1960s…

The television set, that unassuming box often paired with a quirky antenna, possessed immense influence. The glass screen became a source of information and entertainment, but also a powerful tool for mind control and manipulation.

There is only one direct quote from Borges’ story dated April 23, 1983, in the film. In Grimonprez’s adaptation, there’s a place for this fragment:

I hate your face, which is a caricature of mine, your voice that mimics mine (…) So do I, said the doppelganger.

Meanwhile, in the story The Other, Borges wrote:

If something supernatural happens twice, it ceases to be terrifying.

And he suggested a second meeting with his doppelganger, who naturally also bore the name Jorge Luis Borges…

Double Take is a treat not just for Alfred Hitchcock enthusiasts. This unconventional cinematic patchwork, brilliantly interwoven with music from Psycho and The Birds, will satisfy any cinephile who appreciates originality and complex, multi-layered cinema. What isn’t there in this film? Sputnik in orbit; Laika in space; the Cuban invasion; the American dream, morning coffee in a bright kitchen with a view of a perfectly manicured lawn; Khrushchev and Nixon, Khrushchev and Reagan, Khrushchev and Castro—summit talks in every possible configuration; Castro and his doppelgangers, who he used to play tricks on American intelligence agencies; fear of nuclear annihilation; panic, psychosis; apocalyptic moods; UFOs. And all of this framed within the archetypal fear of encountering one’s double. What connects all these phenomena? The fear that some of them might turn out to be real while others remain fiction, and ultimately, the fear of death.

This is what the doppelganger used to symbolize: death. An encounter with a double foreshadowed, at best, great misfortune, and at worst, sudden and unexpected death. Does the meeting of the director with his older self mean he will soon die? It doesn’t make sense—after all, he’s looking at himself years ahead, so he’ll live at least that long. At least. Because this encounter might signify not his own death but that of the other… In Borges’ story, this theme was presented more literally and dramatically, as the younger Borges—the narrator of August 25, 1983—witnesses the older Borges die. The meeting in the hotel is a confrontation with his own future death.

On a deeper, metaphorical level, the encounter created by Grimonprez between Hitchcock and an older version of himself portrays a director torn between the desire to remain true to the grandeur of cinema and the urge to embrace the progress and film for television.

Did Hitchcock and Burrage actually meet but, being thirty years apart, failed to recognize each other, and thus neither of the doubles noted the encounter? It’s possible. Ron Burrage worked in the hotel and restaurant where the director frequented. Could Grimonprez’s cinematic variation on Borges’ writings be more real than it seems? Perhaps…

One thing is certain, however: Alfred Hitchcock would have been intrigued by Double Take. Even if it weren’t him but someone else as the main character of the Belgian filmmaker’s work, upon watching this extraordinary and contrast-filled film, Hitchcock would probably have said: Excellent work!