CREMASTER Explained. Fascinates, Shocks, Lulls…

…if it’s even possible to experience something truly new, unprecedented, and freed from all known principles of film production and narrative creation.

Since 1991, when as a 24-year-old, he climbed walls and hung from the ceiling of New York’s Barbara Gladstone Gallery, dressed only in sneakers, a swim cap, and mountaineering ropes attached to his anus, international critics have been unable to contain their admiration. ‘He is a true enfant terrible (a person who creates uncomfortable situations for others), embodying androgyny (a dual-gender attribute often associated with deities in various religions) and modern decadence,’ wrote the American magazine Newsweek. Germany’s Der Spiegel called him, somewhat less flatteringly, a ‘showmaster of mutants,’ while Michael Kimmelman, chief critic of The New York Times, promptly crowned him the most important American artist of his generation. Even before turning 30, the athletic artist with a passion for climbing and organic substances such as petroleum jelly, beeswax, starch, salt, and petroleum jelly—materials he uses to sculpt spectacular fetish sculptures, photo frames, and sets for his films—began his ascent to the upper echelons of the global art world… Cremaster

We live in an era where it’s exceedingly difficult to surprise the audience, if it’s even possible to experience something truly new, unprecedented, and freed from all known principles of film production and narrative creation. After all, we’ve already had David Lynch with his grotesque Eraserhead, the enigmatic Lost Highway, and the equally puzzling Mulholland Drive. We’ve witnessed the ‘fetishization’ of the human body, something David Cronenberg excelled at. His Videodrome, with scenes of inserting VHS tapes into the abdomen, still leaves a strong impression, while Brundle’s transformation in The Fly was as shocking as it was repulsive with its realistic approach to the feeding habits of a human-fly hybrid. Crash remains, to date, the ultimate homage to the human body, scars, and the intermingling of sexuality with the crumpled metal of a car in a crash, where destruction becomes an act of creating something new, and injuries sustained in accidents act as an aphrodisiac…

What distinguishes Matthew Barney‘s work from these mentioned directors is the absolute lack of narrative in all parts of the Cremaster cycle. Barney, an avant-garde artist, sculptor, and equally fascinated by corporeality and human sexuality, has created an unprecedented work that defies all classifications and does not submit to any objective rules of criticism or evaluation. This cinematic demiurge, freely creating breathtaking sets, has developed his own filmic language for the Cremaster (the title, in line with Barney’s analytical inclinations, refers to ‘the muscle responsible for raising and lowering the testicles’), whose universality and communicative accuracy he trusts so deeply that he forbids his films from being shown with translations into the language of the country where a copy of Cremaster happens to be screened. The limited number of copies is one of the most intriguing aspects of Barney’s cycle; according to unofficial data, as of today, Cremaster 1-5 exists in only 10 copies of the film reel, and the film is regularly shown in just a few art galleries in the USA, accompanied by appropriate exhibitions of Barney’s works. The Cremaster Cycle (aside from The Order, a 30-minute segment from Cremaster 3 released on DVD) has never been officially or unofficially released on any medium, and it’s even difficult to find images from any part of the series online.

Therefore, Cremaster remains a rare gem, and each time it is screened in theaters, it becomes an esoteric event, sparking emotions and drawing crowds eager to experience this extraordinary work. It’s not surprising that during the nighttime screening I attended, Cremaster 3 experienced a tape break (apparently, the film had flown in straight from the Canary Islands), and Cremaster 4 failed to arrive on time from Madrid (I might be mistaken about the city since it was 5 a.m. when the distributor’s representative informed us, and I might have misremembered) and was shown on DVD, thus being moved to the very end of this unusual marathon.

Cremaster, which breaks all known rules of film structure, causality, and character development, also defied chronological order in the creation of its individual parts. Is there another example of an ‘x’-part cycle where the parts were made in a similar order: Cremaster 4 (1995), Cremaster 1 (1996), Cremaster 5 (1997), Cremaster 2 (1999), and Cremaster 3 (2002)? And to turn everything completely upside down, Matthew Barney achieved something seemingly impossible—each subsequent part raised the intellectual and technical level of his works to the limits of today’s technology and his imagination, liberated from any pressure or expectations, remaining true only to his vision, consistently building the world of Cremaster. From Cremaster 4 to Cremaster 3, Barney’s work has remained a fully auteur project, distinctly marked by the hand of a master of ceremonies, who, apart from the first installment, played the most important roles in all other parts. Matthew Barney also performed most of his stunts himself, especially during the remarkable climb up the floors of the Guggenheim Museum in NY in Cremaster 3 and on the operatic stage in Cremaster 5—only in the bull-riding scene at the end of Cremaster 2 was he replaced by a stuntman.

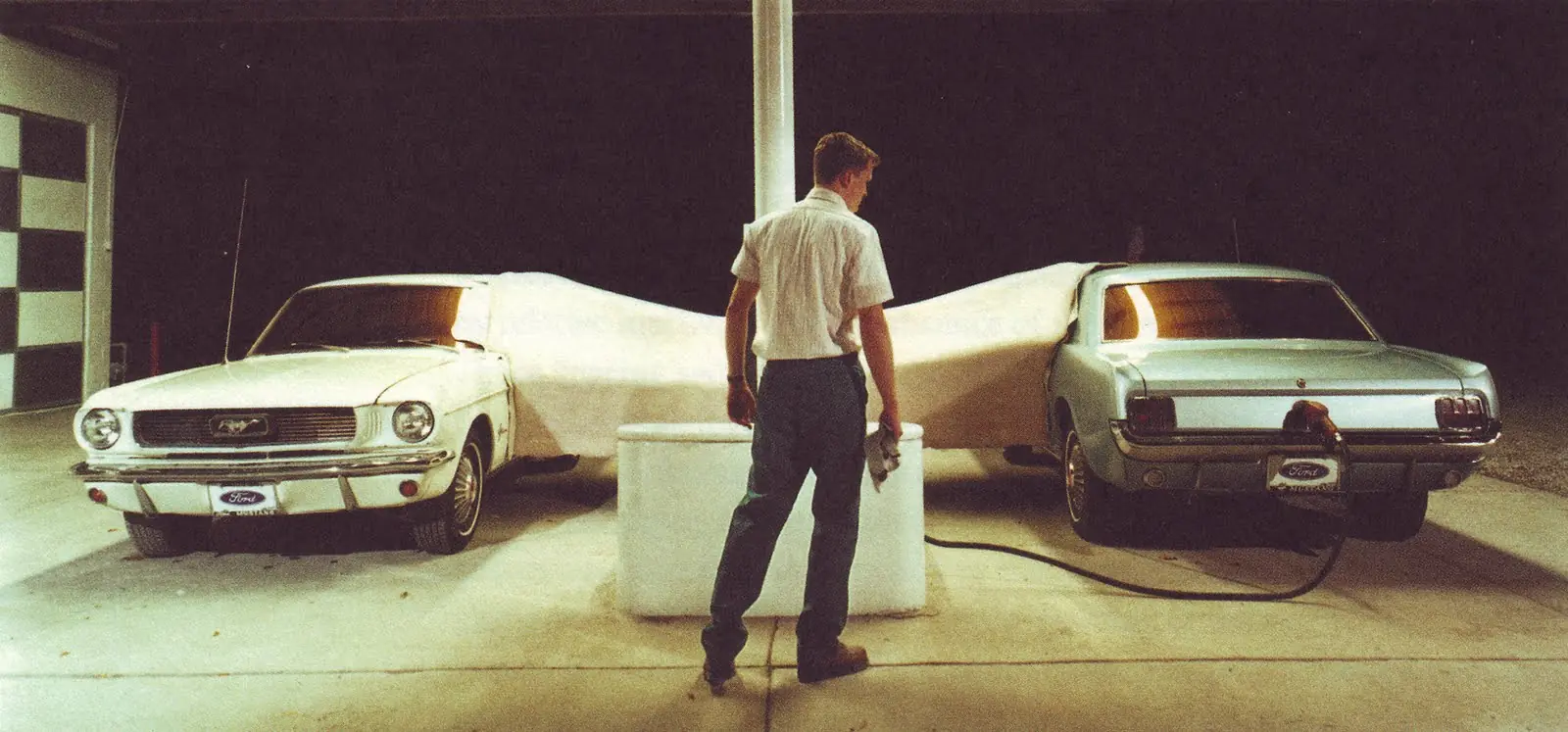

Apart from Barney himself, the characteristic elements of the entire cycle are the organic sculptures made from white rubbery plastic (at least in appearance), symbolism—most often in the form of a pentagram—and dancers filmed from a bird’s-eye view performing elegant choreographic arrangements (female dancers on the stadium in Cremaster 1—styled after the works of Leni Riefenstahl, mounted policemen in Cremaster 2, and a kind of dance involving five cars—again, the pentagram!—that crush an old Chrysler model, with the corpse of Gary Gilmore [more about this figure later in the text] inside, for which this ballet of metal, smoke, and screeching tires takes place on the wooden floor of the Chrysler Building’s hall), and most notably, the sticky goo that appears in every part, in various forms, always as unexpectedly as it is inexplicably. In Cremaster 1, Marti Domination—Goodyear—accidentally finds this secretion under the tablecloth covering a table with grapes (the ‘scene’ takes place on the deck of an airship floating above a stadium); in Cremaster 2, the waxy paste is persistently placed on a piece of string by Barney himself—playing Gary Gilmore (the murderer who, in the 1970s, was sentenced to death for killing a Mormon gas station employee, and who was allegedly the grandson of Harry Houdini—the role Barney plays in Cremaster 5). In Cremaster 4, Matthew Barney literally bathes in his favorite sticky, stretchy, and viscous substances, as he, in the role of ‘The Loughton Candidate,’ makes his way through an underground tunnel filled with them.

The Cremaster cycle lasts a total of exactly 400 minutes, and it’s 400 minutes of the most captivating boredom I’ve ever experienced in a cinema. From ‘nothing happening,’ Barney creates the greatest asset of his oneiric cinematic works. Excluding Cremaster 4 (the fourth part, shot chronologically as the first, presents a completely different aesthetic compared to the rest of the cycle; the camera work is dynamic, the cuts are more frequent, there are many shaky shots from a handheld camera, and the whole film, from a technical standpoint, seems like Barney’s exercise, a practice piece before crafting the magnificent and meticulously refined remaining parts), the entire cycle is built upon silence, the contemplation of successive sublime shots, beautiful and inventive imagery, slow panoramas, lazy camera movements, slowing the pace to the point of lulling the viewer into a trance, and extraordinary staging ideas: for example, the giant from the prologue of Cremaster 3 with a few miniature sheep standing at his feet, the symbolic execution of Gilmore, riding a bull in an arena located on a Canadian glacier: Bonneville Salt Flat in Cremaster 2, or the car race on the tracks of the Isle of Man.

The atmosphere is also constructed from trivial and (seemingly and not so seemingly) senseless activities, which are performed by the characters with extraordinary reverence, meticulousness, precision, and dedication, such as pouring beer in the bar of the Chrysler Building, Aimee Mullins (a model and athlete listed by People magazine among the 50 most beautiful people on our planet, who has no legs below the knees – something that Matthew Barney brilliantly utilized in Cremaster 3 by characterizing Aimee as a leopard-woman with thin lower limbs, and in another scene, dressing her in porcelain high-heeled shoes – cinema history surely won’t overlook this!) cutting out pieces of potatoes in Cremaster 3, grapes regularly flying out of the heel of Goodyear Girl’s shoe in part 1, cementing the elevator and the endless ‘destruction derby’ in part three, the never-ending pointless car race in Cremaster 4 (though according to the distributor’s descriptions, the race of the ascending and descending coils has some purpose after all ;), Gary Gilmore trapped inside two cars connected by an organic tunnel at a gas station, or finally, the aforementioned climb by Matthew Barney himself.

If we add the fact that, except for a brief dialogue at the finale of Cremaster 2, not a single word is spoken in any of the other parts, we can be sure that this isn’t just a film but a peculiar work of art that influences the viewer through the suggestiveness of its imagery, characters, the symbolism of places, shapes, and meanings of objects – such as Masonic attributes: the compass, the plumb line (symbolizing introspection), the hammer (helpful in shedding faults), and the trowel (morality and justice), as well as the hewn stones (supposedly, Freemasons were the first to master this skill) that the candidate Mason – Matthew Barney – carries in the pockets of his leather apron, representing the symbol of creating a better society. These objects are the focal point of Cremaster 3, serving as a kind of allegory for the construction of the Chrysler Building, the creation of the ideal structure, emphasized by breathtaking aerial shots that show the newly erected, steel skyscraper in all its glory, with ribbons flowing from its highest windows.

However, the Cremaster isn’t solely about its technical and substantive aspects. The individual parts of the cycle feature such unconventional figures from show business as Dave Lombardo, the former leader and drummer of the band Slayer (apparently Gary Gilmore’s last wish before his execution was a phone conversation with Dave Lombardo himself, depicted in Cremaster 3 as dark, hoarse screams into the phone, performed by Lombardo himself, whose body is covered by hundreds of bees – one of the main elements in Cremaster 2), the renowned Swiss actress Ursula Andress (still best known as the first Bond girl, kissing Matthew Barney himself in Cremaster 5, or, if you prefer, Matthew Barney kissing Ursula Andress!), the American disabled model Aimee Mullins, whom I mentioned earlier, writer Norman Mailer, representatives of the Masonic lodge, and the famous American sculptor, Richard Serra. This collection of curiosities added an extra touch of uniqueness and originality to Cremaster.

The Cremaster Cycle exists thanks to this (and the aforementioned features) beyond all boundaries, classifications, and understanding. It is like an art exhibition that everyone experiences in their own way, either accepting or rejecting it. It is precisely due to the controversy and divided opinions that Cremaster continues to evoke emotions, fascinates, shocks, lulls, and simultaneously doesn’t let you take your eyes off it. But can anyone who, in art galleries, performs an unparalleled performance, jumping on a trampoline with plastic, surgical tubes tied to their arms while simultaneously drawing on the walls – could such a person create a film that could fit into any rational template of understanding or be deciphered using any existing key? Matthew Barney (privately the husband of Björk!) indulges in autoeroticism, exploring the dual-gender nature of humanity (which he expresses, perhaps primarily, in Cremaster, where most of the hybrid characters lack defined sexual organs), cherishing above all his own sexuality and the iron condition of his body, creates fetish-sculptures, and is currently the most eccentric, postmodern, and liberated creator in the world, with Cremaster being his most comprehensive and accurate calling card. A calling card that, unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), not everyone can see…