CITY OF WOMEN Deciphered: A Masterpiece or Not?

The main character, supported by nurses, nuns, female doctors, and midwives, amidst pitiful moans, screams, and complaints, is dragged through a long hospital corridor. A vision of beds with mustached and strong men who breastfeed, cradle, caress, change, and lull their infants to sleep.

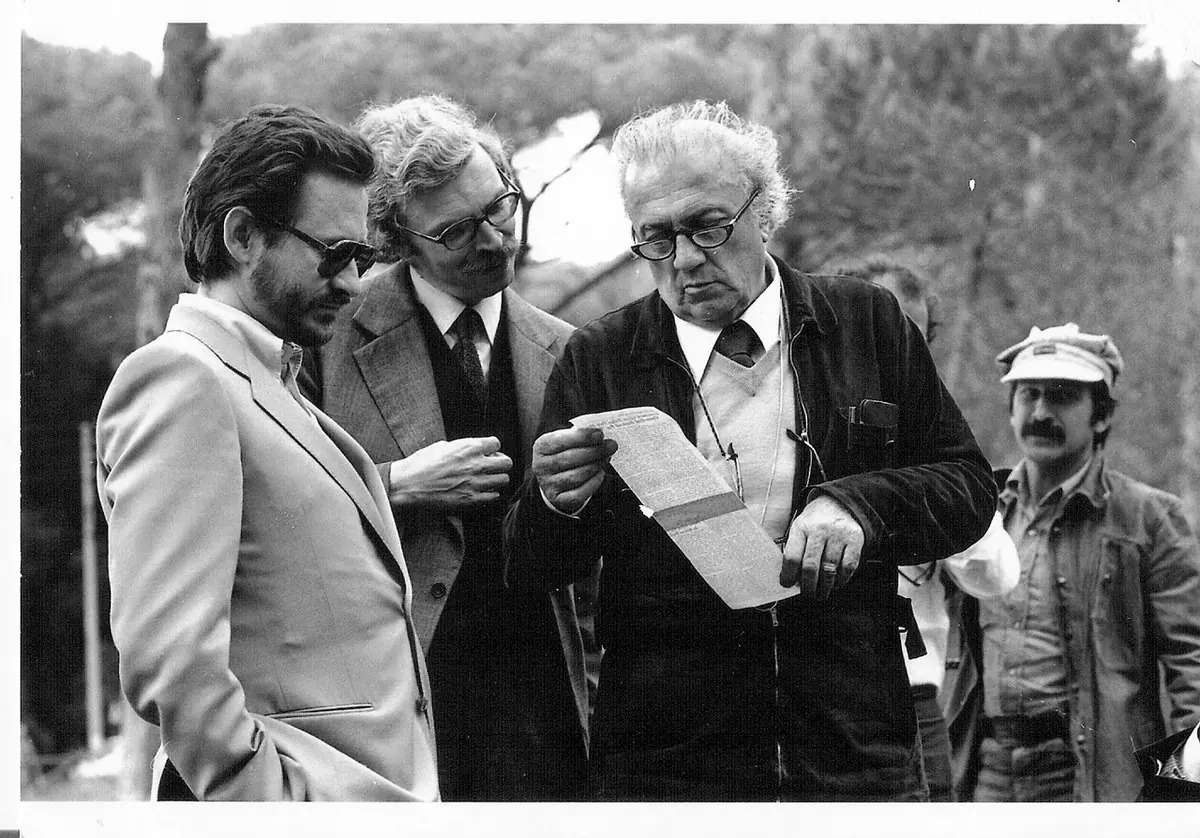

This is how the first paragraph of a small introductory sketch of City of Women looks, found by Bernardino Zapponi, the film’s co-writer, “accidentally in one of the forgotten folders (how many documents were lost in this way!).” Anyone even slightly familiar with Fellini’s remarkable 1980 work quickly realizes how little survived from the original concept for the opening. In fact, only the dream remained—a dream as the film’s narrative organizer, the dominant interpretation, a film-dream.

And the dreamer is a certain Snaporaz, perhaps the most enigmatic character among all those Marcello Mastroianni played in Fellini’s films. We know almost nothing about him. A man in his fifties, traveling by train, elegantly dressed, with a tie around his neck and oversized glasses on his nose. A bit clumsy, awkward, easily swayed by feminine charms, which lands him in no small amount of trouble. In pursuit of a beautiful stranger, our hero makes a spontaneous decision to leave the train. He finds himself at a makeshift station, in the middle of nowhere—just him and the woman he’s been following. Hypnotized, enchanted, Snaporaz follows her into a peculiar building located in the heart of the forest—a hotel overflowing with women gathered for a feminist congress.

At this point, the exposition ends, and the narrative picks up the pace of an express train. Dreaming of returning to the station, Snaporaz is caught up in a whirlwind of mysterious events—deemed an intruder, he must flee the hotel, ending up in a giant roller-skating room, a boiler room inhabited by a giantess-witch, Dr. Xavier Katzone’s enormous estate, and finally inside a woman-shaped balloon that lifts him high into the sky. The protagonist moves from place to place unexpectedly, following Fellini’s beloved dream logic (Fellini, a devoted follower of Carl Gustav Jung‘s psychoanalytic theories, sometimes called him “his older brother”). Situations change abruptly without rational motivation. They are somewhat indeterminate, unfinished, as if in a state of unstable, fragile equilibrium. At any moment, they can turn into their opposite, surprising us with an unforeseen twist. […] Causal relationships cease to function. They are replaced by the law of metamorphosis, systems of analogies and correspondences. Like in The Hourglass Sanatorium—just crawl under the bed, and you might find yourself in an entirely different time and space. Nothing in City of Women is fixed, certain, or permanent—and that is the most fascinating thing about Fellini’s film and his entire oeuvre. This constant, unstoppable metamorphosis.

Snaporaz’s long, extraordinary journey is tinged with mythological motifs. This is, of course, tied to Fellini’s personal obsessions, which found their fullest expression in Satyricon over a decade earlier, and to the unnamed profession of the main character, a professor specializing in Greek and Roman mythology. The most significant myth in City of Women is the one about Theseus and his journey to Crete to slay the Minotaur. As Snaporaz falls asleep, he enters the Labyrinth, something Fellini signals at the film’s beginning when the train enters a dark tunnel (a magical passage). The protagonist’s main goal is to find the exit—the way back to the station—with the help of Donatella-Ariadne, whom he meets at the hotel and who, as she says, “always carries a needle and thread.” In the film’s climax, unlike the heroic Theseus, Snaporaz reaches the labyrinth’s center—a giant stone arena where a monster awaits. But after a laborious climb, he finds no monster, just an old servant who leads him to an enormous balloon shaped like Donatella. By the end of City of Women, the protagonist is revealed to be both Theseus and the trapped Minotaur, destined to die. The balloon carrying him is eventually shot down by the real, physical Donatella-Ariadne, causing Snaporaz to awaken from his dream, thus leaving the labyrinth (in the final shot, the train, just like at the film’s beginning, enters a tunnel again).

But let’s dig deeper. What else is City of Women about? Let Fellini speak for himself:

It seems to me that the audience doesn’t realize that City of Women is a film about cinema, cinema seen as a woman, through its femininity, through the masturbatory discovery of its femininity. And I don’t mean the scene where twenty boys are masturbating in a huge bed while watching a film, but rather the film as a whole, the way it expresses itself, the things it quotes in a hidden way.

Fellini’s obsession with self-referentiality had already haunted him during the making of 8½ and grew stronger over time, reaching its peak in the final phase of his career—from The Clowns onward.

It’s no different in City of Women. Snaporaz, climbing a ladder, repeatedly chants the characteristic, charming phrase reminiscent of a magical spell (Asa Nisi Masa?), “Smick! Smack!”, and for a moment, looks directly into the camera; mysterious gentlemen in suits address the protagonist by the real name of the actor playing him – calling him Marcello (a similar technique can be found at the very beginning of the film – when Mastroianni’s name appears in the opening credits, a tender, laughing female voice calls out from the speakers: Marcello again? Maestro, please…); the fiery tirade delivered by the seductive woman from the train during the congress is directed at none other than the director himself – the women gathered in the hall are called “puppets,” “an excuse for another primitive, animalistic tale,” and the author of this tale is labeled as the “grim, vain, burned-out Sultan.”

These examples could go on, but I would like to highlight one more, perhaps the most significant – Snaporaz’s passive attitude, as throughout the entire film, he mostly surrenders to the unexpected events rather than actively participating in them. This is clearly illustrated by the means of transport (train, motorcycle, car, cage-cart) the protagonist travels in. Always as a passive passenger, never as an active driver who has real control over the situation. As Maria Kornatowska observes:

His behavior resembles that of a moviegoer in a cinema – a voyeur allowing himself to be hypnotized, drawn in, almost sucked into an illusionary reality arranged for his amusement.

Snaporaz as Theseus, Snaporaz as the Minotaur, Snaporaz as the viewer.

Of course, the film also references other myths and mythological figures. Most notably, there is Cerberus, recognizable in the three cars driven by drug-addicted women who follow the helpless Snaporaz in one scene, and in the three dogs at Dr. Katzone’s estate (who later reappear in Interview as guard dogs for Anita Ekberg). Odysseus also comes to mind, with his years-long journey full of unforeseen obstacles and unexpected stops, strongly resembling the adventures of the simple-minded Snaporaz, who, like the ruler of Ithaca, merely wishes to return home – to the starting point of his journey (the train).

When closely examining City of Women, another, less obvious thread should be explored – one that connects to the figure of the co-writer, Bernardino Zapponi, an Italian writer and poet, a declared fan of Franz Kafka’s work, whom Fellini also highly esteemed. It’s worth mentioning that the La Dolce Vita director had long planned a monumental (how could it be otherwise?) adaptation of America (one of the main threads in Interview even revolves around the preparations for this adaptation). Unfortunately, the project fell through, joining the ranks of his never-completed works, sitting alongside the famous The Voyage of G. Mastorna and A Love Story (a project once planned in collaboration with none other than Ingmar Bergman). Hence, we won’t find a true Kafka adaptation in Fellini’s filmography. However, this does not mean we shouldn’t search for Kafkaesque elements in the works of the Magician of Rimini, as Zapponi calls him in his book. The co-writer of City of Women even urges us to do so, writing that Kafka was an inexhaustible source of inspiration for Fellini, omnipresent in every one of his films.

Indeed, there are solid grounds for interpreting City of Women through a Kafkaesque lens (as awful as that adjective may be, it’s quite useful). The atmosphere of a nightmarish dream, the irrational, overwhelming sense of guilt haunting the protagonist, his passive and submissive stance toward reality, the overt hostility and rejection from his surroundings, permanent isolation, and finally, the judgment (the women’s tribunal), the sentence, and its execution – all these elements can be easily found in Fellini’s film. As he falls with the punctured balloon, Snaporaz, in one of the final moments of his life-dream, spots a beautiful, blue-eyed girl – the ideal woman. Fascinated by her sudden appearance and irresistible charm, he asks, “Who are you?” Maria Kornatowska rightly points out that this moment closely resembles the scene preceding Josef K.’s death in The Trial, where the protagonist “notices a window opening in the distance and wonders who the person opening it might be.” Death and the mystery that accompanies it. However, Kornatowska concludes, and I fully agree, that Kafka’s stories resemble haunting nightmares from which there is no escape or salvation. Fellini loves life too much to fully succumb to the dark side of dreams. In the tunnels of his films, there is always a glimmer of light, even in the farthest distance. A rising dawn. In City of Women, that dawn is, of course, the protagonist’s final awakening – placing everything we’ve seen on screen within a grand parentheses. A nightmare, but by no means a tormenting one.

Films are never created in a vacuum, and City of Women is a perfect exemplification of this idea. Bernardino Zapponi emphasizes in his book that during the time between writing the screenplay and the film’s production, an exceptionally violent wave of feminism erupted. Roman feminists took over a center on Governo Vecchio Street, occupying it in protest – the caricatured vision of the congress, which made it into the City of Women script (and later the film), suddenly didn’t seem so far-fetched. Worried by the developments, Fellini decided to send Zapponi to the occupied building to investigate and consult the screenplay with the group of rebellious feminists (provided, of course, they were interested in the project). Zapponi described the trip to Governo Vecchio in his characteristic literary, humorous style (which may have negatively impacted the credibility of the account):

I timidly crossed the threshold of that sanctuary. In the spacious vestibule, my eyes fell on a shattered, bottomless mailbox and a pile of letters scattered on the floor, alongside a sign on the wall: ‘Dear feminists, it’s not a man asking you to install a new mailbox,’ signed ‘The Postman.’ I climbed the stairs to the large rooms upstairs. Everywhere, only women. I felt like a black man touring the headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan. They looked at me, frowning, as if asking: what the hell are you doing here? I explained that Fellini and I had written this screenplay, and although the action takes place in a completely imaginary realm, given recent events, we wanted to acknowledge the birth of a new feminist “consciousness” and would happily enrich the script with details of the protest they were leading…

Ultimately, the group from Governo Vecchio declined the screenplay consultation (Fellini later reached out to more cooperative feminists), advising Zapponi only to read their pamphlets, listen to a few of Magdalena’s lectures, and thoroughly delve into feminist ideology before coming back with a prepared list of questions. (I personally think that’s a very reasonable suggestion.) How much truth and how much of Zapponi’s cinema and literature-soaked imagination is in this strange story? I fear we’ll never know the answer to this lengthy question.

City of Women premiered in Italy on March 28, 1980 – nearly 45 years ago. It entered theaters amidst a cloud of moral scandal, which “initially acted like a magnet for audiences” (a similar situation occurred twenty years earlier with La Dolce Vita). However, the film quickly disappointed those who attended due to the controversy – for such viewers, it proved too long, tiresome, and difficult to digest. Feminists weren’t fond of it either, seeing in it “a mocking, distorted image of their own stance.” Even the reviews were mixed, with many Italian journalists shouting in headlines that: The master repeats himself! He’s spinning in circles! He has nothing new to say! (a constant critique of Fellini’s later films – perhaps it’s the critics, not the artist, spinning in circles). Did anyone actually like City of Women? Most likely, only the true, dedicated fans of the Magician of Rimini – those who understand that artists who create their own mythologies (and Fellini certainly belongs to that category) are writing the same, multi-volume novel, painting the same picture, and exploring the same “personal” world throughout their entire careers. They’re making the same film – in Fellini’s case, the same masterpiece.