The most memorable MOVIE MURDER SCENES

Kill, how easy it is to say. Certainly easier than writing a list about it. Killing is an everyday thing on screen. This is a topic for many publications and even film literature. And always with this type of selection some important scene will be missed. Creating a description of the most suggestive sequences, where one person takes the life of another or a third, aimed at creating an impression of horror and shock, often also moving, means a difficult choice. There is a certain simplification of the task: it does not say that the more brutal and gory the scene, the better the emotional result on the part of the viewer. One moment of murder can have more impact and meaning than mass murders in a typical slasher, gore movie or ordinary “stock” where the corpse is too dense and the mother’s head (sometimes literally) served on a plate. Much depends on the dramaturgy and climate, context, convention, meaning or justification of a given murder. The performance of the actors and the work of the director also play a significant role in building the effect. Sometimes such scenes can also have a negative impact on the viewer. Fascination with the crime shown may be born. After all, there have been cases of murder inspired by a film record, and the cinematic matter also draws from authentic killings. Below is a subjective list of the most interesting and memorable on-screen kills. In some descriptions, references were made to other scenes that could not be included in the general list due to their volume. The sequence of the scenes listed is random.

WARNING: MANY DETAILED SPOILERS!

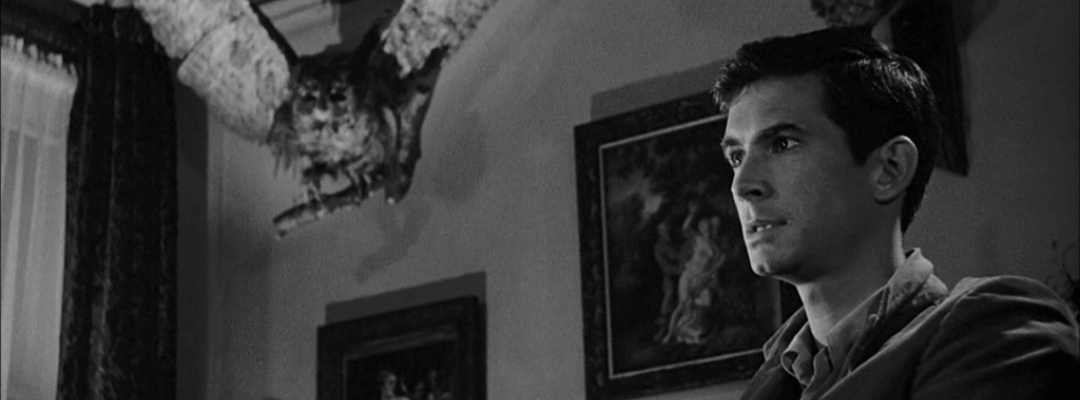

Psycho (1960)

It could not be missing from the list of this legendary scene in the shower, about which almost everything has been written, so it does not make sense to disassemble it into prime factors. Probably no movie murder is so often quoted and reproduced. No wonder, because since Hitchcock’s film set a new framework for the thriller, it had to include at least one scene that is a showcase of the story. It was surprising at the time that the main character dies in the middle of the film and is replaced by other leading characters. Of course, in fact, the main character is Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins, unforgettable in this role), but the viewer is convinced that he is not behind the murder. The scene caused real “shower phobia” for a long time. Interestingly, it is not shown at all that the knife touches the body. We have a classic scream of the victim, a nervous score with a thrill plays in the background, we see the perpetrator’s shadow, a body with a curtain falling down, water flowing with blood into the drain. It was enough to save this moment as a milestone of cinema, to which numerous artists refer, and the number of references is difficult to count.

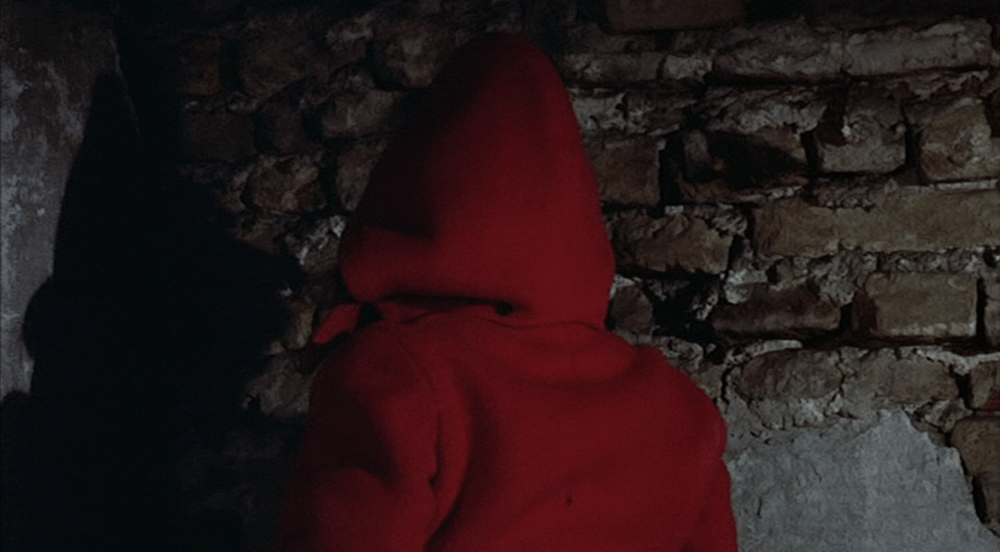

Don't Look Now (1973)

It’s still one of the most thrilling endings in more than just horror movies, even though the movie has aged as a whole. There is some kind of inevitable fatalism in this culmination. Donald Sutherland’s father follows the figure in the red cloak, thinking it’s his dead child. The man, unlike his wife, did not believe the warnings of the two sisters who acted as mediums. The figure lures Baxter into the dark corners of an abandoned cathedral. When she hits a dead end, she pretends to cry and the man addresses her as his daughter. The figure turns around, it is revealed that he is a dwarf armed with a knife (razor?), and Baxter and the sight stands speechless and motionless. The moment the dwarf shows his deranged old woman face, we shudder because both Baxter and the viewer had the innocent, childlike face of a girl in their minds. Lilliput cuts his throat, the man dies in convulsions, blood oozes from his neck, the last events of his life flash before his eyes. Questions arise about the mystery of this scene. All indications are that John Baxter was a medium himself, saw things related to his death, more or less clear warning signs that he could not read properly. The warnings came not only from the haunted sisters, but were also sent by the city itself, Venice. The dwarf was a marauding killer, and his clothes were deceptively similar to the red coat in which Baxter’s daughter had drowned. Already at the time of the unfortunate accident, before leaving for Venice, my father received a sign while working on a project to renovate a historic church. The moment his daughter drowned, blood flooded the photo seen under close-up. For a fraction of a second, there is a figure of a dwarf in the church. Baxter had not foreseen his destiny, and his daughter’s death foreshadowed his own nemesis. Perhaps if a new version of Nicolas Roeg’s film is made, these shivering theories will be much more developed. Scenes of a similar nature include the one in Carrie De Palma, when the title character is killed by her mother, but she still manages to kill her using her telekinetic abilities.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

“You have the right to kill me, but you have no right to judge me” – these words of Colonel Walter Kurtz perfectly reflect the scene in which Captain Willard kills a senior officer at his own request. Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now based on Joseph Conrad’s book is a mystical journey through the madness and absurdity of the Vietnam War seen through the eyes of Captain Willard chosen for a very risky task. Command recognizes that one of their best men, a colonel close to being made general, with an almost exemplary service record, has lost his mind and is out of control. Kurtz has become the lord and ruler at the edge of the war-torn world, he has created his own kingdom, where the natives serve him as subjects. Willard is supposed to find him and remove him from power, that is, kill him. The captain, sailing down the river towards Kurtz, to the place where the devil says goodnight, is an eyewitness to the horrors and nonsense of war. What’s more, he is increasingly aware of the hypocrisy and falsehood represented by his command. After meeting Kurtz, he only confirms this. The found colonel is a god of war with a broken soul. Powerful and enigmatic, Kurtz is somewhere between good and evil, madness and normality. He opposed the hypocrisy of the outside world and its representatives, so he built his own “state”, where he exercises very bloody power at times. Kurtz could easily kill Willard if he deemed him unworthy of his death sentence. Meanwhile, the colonel, who had been through the horrors of war, had seen too much and no longer saw the point of living any longer, was waiting for someone like Willard who sincerely understood his intentions. The captain, knowing that Kurtz wants to die like a soldier and not like a coward and a liar, attacks him at night just as the colonel is finishing his notes. Willard machetes Kurtz, who does not try to defend himself, which coincides with the ritual killing of a buffalo by the natives, which is a kind of sacrificial mystery. Kurtz’s last words, “horror… horror…” match the colonel’s last recorded sentence for Willard to convey to the authorities: “Drop the bombs, kill ’em all!” It’s a kind of testament. Why did Kurtz want to doom his kingdom and his “children” to destruction? Perhaps he was sure that without him the whole settlement had no reason to exist and it was he who wanted to decide about its further fate on the basis of “God gave, God took away”. The long, dark and heavy scene is not easy to read, but it gives food for thought, which makes Coppola’s picture much more than a war drama. It can be safely treated as a philosophical treatise adapted from the time and place of the action of Heart of Darkness to Vietnamese conditions. In the original version of Coppola’s work with the end credits, we see Kurtz’s wish fulfilled, his jungle asylum is completely bombarded, and the flames of the fire in the middle of the night convey the beauty and horror of the apocalypse as the absolute fulfillment of the colonel’s last will just after his death.