CHARLIE CHAPLIN. In the End, Everything is a Gag, Vol. 1

Hundreds, thousands, or maybe even tens of thousands of film reels have been resting for years on the shelves of film archives around the world and in the attics of people who have no idea what treasures lie in rusty, round cans. Not a year goes by without a researcher interested in this period of cinematography discovering something new—a material that, despite the deteriorated image, brings back the times and figures of people who have long since passed away.

Cinema halls can still find room for these kinds of productions, and not only during film festivals. Just recall the year 2011 and the spectacular success of The Artist by Michel Hazanavicius, a film that openly references the time before The Jazz Singer (the first sound film). However, this is a kind of swan song because it’s hard not to feel that in an era where even classics from the 1970s are seen by many as relics of a bygone era, silent cinema has become little more than a faint mention in history textbooks. That’s the way of things—there’s no need to tear our clothes in despair—but sometimes it’s truly worth slowing down, cutting a few new releases from your movie schedule, and looking back. If only to meet Charlie Chaplin again.

This and the following texts in this newly launched series might provide such an opportunity. Those who know the filmography and biography of perhaps the most famous representative of the silent film era can once again meet the good old Charlie. Those who are just thinking of getting acquainted with what he left behind will be able to treat this series as a guide. I invite you to journey back in time and immerse yourself in a world that now exists only thanks to our memory.

The Kid

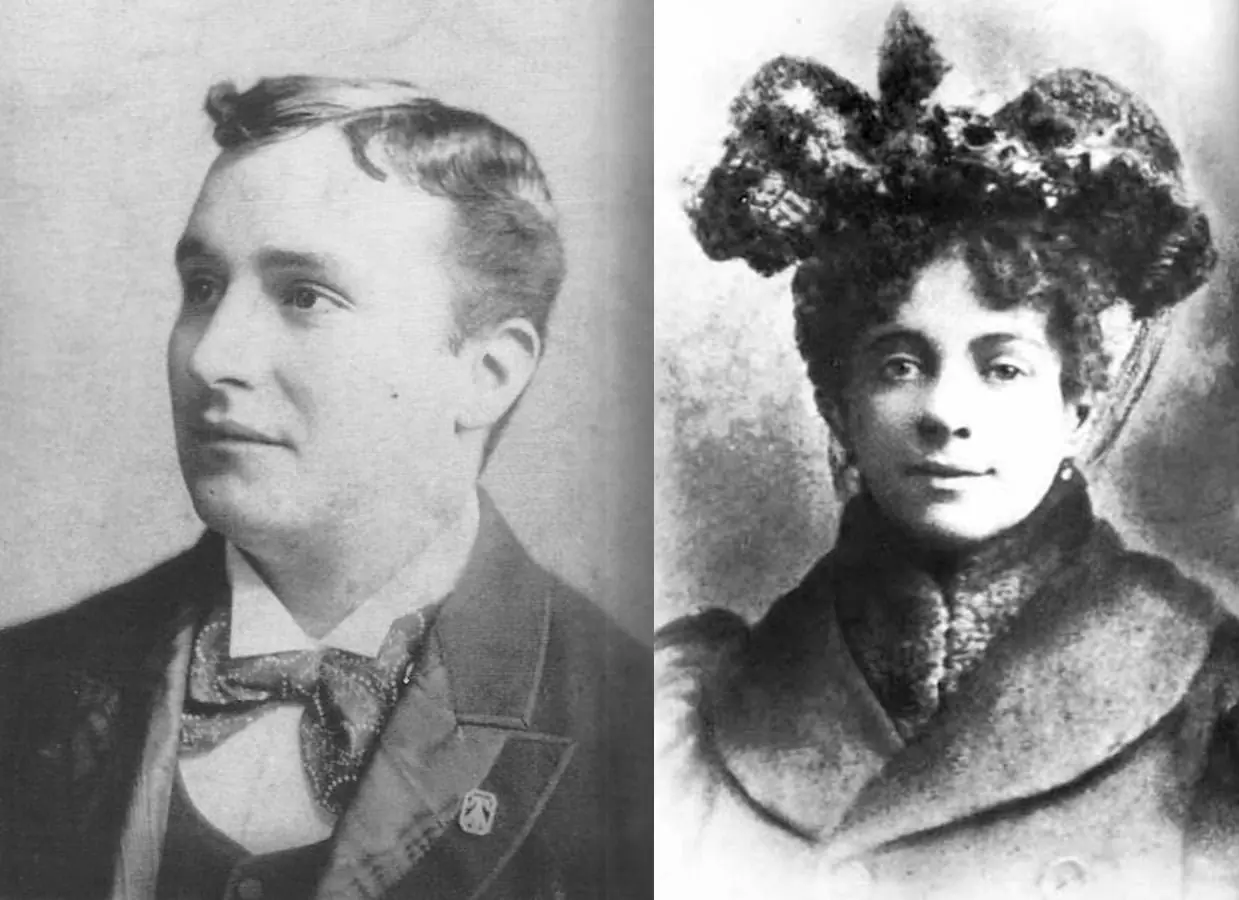

Hannah Harriet Pedlingham Hill, better known by her stage name Lily Harley, began her career at the age of sixteen. The modest daughter of a shoemaker, in love with Lillie Langtry—the star of the late 19th-century stage—decided to leave her father’s workshop and try her luck on the stages of British music halls. These types of performances were extremely popular entertainment among Victorian crowds, combining elements of theater, musical, dance, acrobatics, and cabaret. The audience wasn’t expected to maintain theatrical seriousness but rather a good sense of humor, so it’s easy to see that this world wasn’t the most friendly to young girls. Early in her career, during performances in Shamus O’Brien, Lily met Charles Chaplin Sr., who earned a living through singing. Their romance lasted probably for several months, but neither took steps toward marriage. Furthermore, Lily set her sights on another man, Sydney Hawkes, with whom she left Britain to live in South Africa. However, the relationship with Hawkes turned out to be a total failure. According to many sources, the young woman was forced into prostitution by him. In 1884, Lily returned to the United Kingdom pregnant by Hawkes (probably). Charles was waiting for her back home. After giving birth, Sydney took his surname. On June 22, 1885, the couple married at St. John’s Church in Walworth. Less than four years later, on April 16, 1889, their first child together, Charles Spencer Chaplin, was born. Throughout her pregnancy and afterward, Lily continued performing on the stages of British music halls.

However, from the late 1880s, her health began to deteriorate rapidly. Doctors were unsure how to help her. From medical records analyzed years later, it is highly likely that it was during this time that Lily contracted syphilis, which later led to mental illness and contributed significantly to her death. From the 1890s, her relationship with her husband also declined, as he spent more time away from home and turned to alcohol. His addiction destroyed his career and, eventually, with the help of cirrhosis of the liver, claimed his life in 1901. However, Charles Chaplin Sr. was never really present in young Charlie’s life. Despite her illness, Lily continued to try to earn a living through performing. She also sought to rebuild her life to provide for her family. From a brief relationship with Leo Dryden, her third son, Wheeler, was born. Until 1893, Dryden stayed with Lily and acted as a father figure to her three children. However, Lily’s illness won out, and when syphilis significantly affected her mental condition, Dryden left, taking Wheeler with him. Wheeler only learned that Charlie Chaplin was his brother in 1915, when his father saw the comedian on a cinema screen and decided that Wheeler should know.

When Lily was left alone, her husband was drowning his life in alcohol, and Charlie was four years old while Sydney was eight. In 1894, during one of her performances, Lily literally lost her voice. It was then, in a rather unprestigious venue in Aldershot, that Charlie Chaplin first took to the stage. The five-year-old sang in place of his mother, saving the evening and her meager earnings. It turned out the boy was a natural on stage. Soon, Lily had to give up performing entirely. She settled in London’s Kennington with her two sons, trying to make ends meet through small shoemaking services. Around 1896, she was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, while her sons were sent to an orphanage in Lambeth, which today has been transformed into a museum of cinematography.

From that time on, the brothers’ lives were never the same. Brief improvements in their mother’s health gave them hope for a return to normal life, but Lily was never able to stay out of the hospital for more than a few months. The boys attended orphan schools and lived in shelters. In 1898, after another of Lily’s breakdowns, they were sent to live with their father, whom they barely knew. Charles was then at the peak of his alcoholism. After two months, Charlie and Sydney were taken from him by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC). Sydney eventually joined the navy, leaving Charlie in an even worse position. In the early 20th century, the teenage Chaplin often slept on the streets and sought food in places not meant for that purpose. The stage became an escape from daily problems and a way to earn a few pennies.

The Footlights

Although Charlie’s first stage performance, substituting for his mother, was just a one-time incident, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, we can already speak of the beginnings of his real career. Through his father’s connections, between 1899 and 1900, ten-year-old Charlie began a small tour around Britain with the dance group The Eight Lancashire Lads, entertaining music hall audiences with young boys’ dances. Although the group, founded by Billy Cawley and William Jackson, was generally well-received, Chaplin quickly realized that dancing was not the form of expression he preferred. Around the same time his mother’s mental health crises worsened, Charlie decided to approach a theater agency in London’s West End. His first role was at the age of fourteen in a production titled Jim, a Romance of Cockayne, where he played a boy selling newspapers. The play wasn’t well-received by the audience and closed after barely two weeks. However, the agency director saw potential in Chaplin and cast him in the same role in a much more popular production, Sherlock Holmes, produced by Charles Frohman. The boy toured extensively throughout Britain, participating in three large tours. Both audiences and critics received him warmly, and he even performed alongside William Hooker Gillette, who was then the most famous Sherlock Holmes actor on the British Isles. The collaboration with Conan Doyle’s character ended in 1906, after which it was time for comedy.

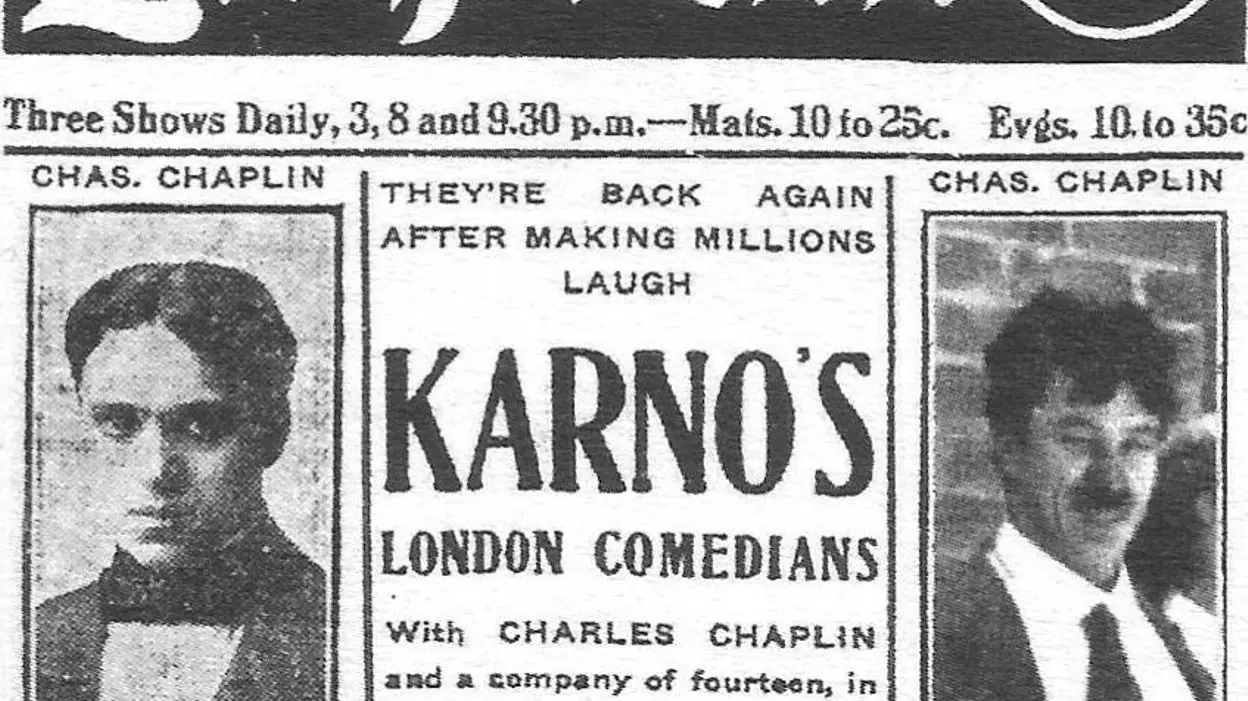

In 1905, Charlie’s brother, Sydney, who had returned from military service, also decided to try his luck in the entertainment business and joined him in Sherlock Holmes. After the play concluded, the Chaplin brothers debuted with their first comedic performance, Repairs, around 1906. Their paths diverged again for a while, though they would cross many more times in the future. Sydney signed a contract with Fred Karno, considered by many to be the father of slapstick comedy. It’s said that he popularized the famous gag of a pie hitting an unsuspecting person in the face. Charlie returned to the stage.

Between May 1906 and June 1907, Charlie traveled across Britain with the show Casey’s Circus. By the time the tour ended, the now-eighteen-year-old Chaplin struggled to find new work, discovering that going it alone was much more difficult than he had anticipated. Meanwhile, Sydney had risen to become one of the main stars of Fred Karno’s troupe. His older brother quickly secured Charlie a spot, although Karno initially saw little potential in him, describing him as a “pale, scrawny, and gloomy-looking boy, too shy to succeed in theater.” However, after Charlie’s first performances, Karno quickly changed his mind and signed a contract with him. For the next few months, the boy, approaching his twenties, played minor roles. He didn’t take center stage until 1910 when he played the lead in the sketch Jimmy the Fearless. From there, things moved faster. By mid-1912, Chaplin was constantly on tour, receiving many positive press reviews. In early October, he embarked on another British tour with Karno’s group. After half a year on the road, a representative from New York Motion Picture Company—a film studio that later became Keystone—spotted Chaplin on stage and thought he would be perfect to fill the gap left by Fred Mac, who had left the studio after disagreements. Thus, at just under twenty-five years old, Charlie found himself in front of the camera.

Mack Sennett and the Keystone Studio

Mack Sennett’s studio, Keystone, was founded in 1912 with the support of the New York Motion Picture Company. Over several months, primarily through slapstick comedies, which were then known as “flickers,” it gained a strong position in the American film entertainment market. Sennett’s comedies were characterized by their fast pace, numerous simple gags such as pies hitting characters in the face, chase scenes, and boldness in defying social conventions. Among the studio’s iconic features were the Sennett Bathing Beauties, a group of women in swimsuits featured in promotional materials and short sketches. Chaplin signed a contract with Keystone in August 1914. Although he wasn’t a fan of the films produced by Sennett, he thought that trying his hand in film could be a great alternative to theater work. Moreover, Chaplin was interested in directing from the beginning, and a contract with one of the most active film companies allowed him to learn the specifics of working on set and the technical aspects of filmmaking. The contract was signed for one year. During that period, Chaplin appeared in about forty productions.

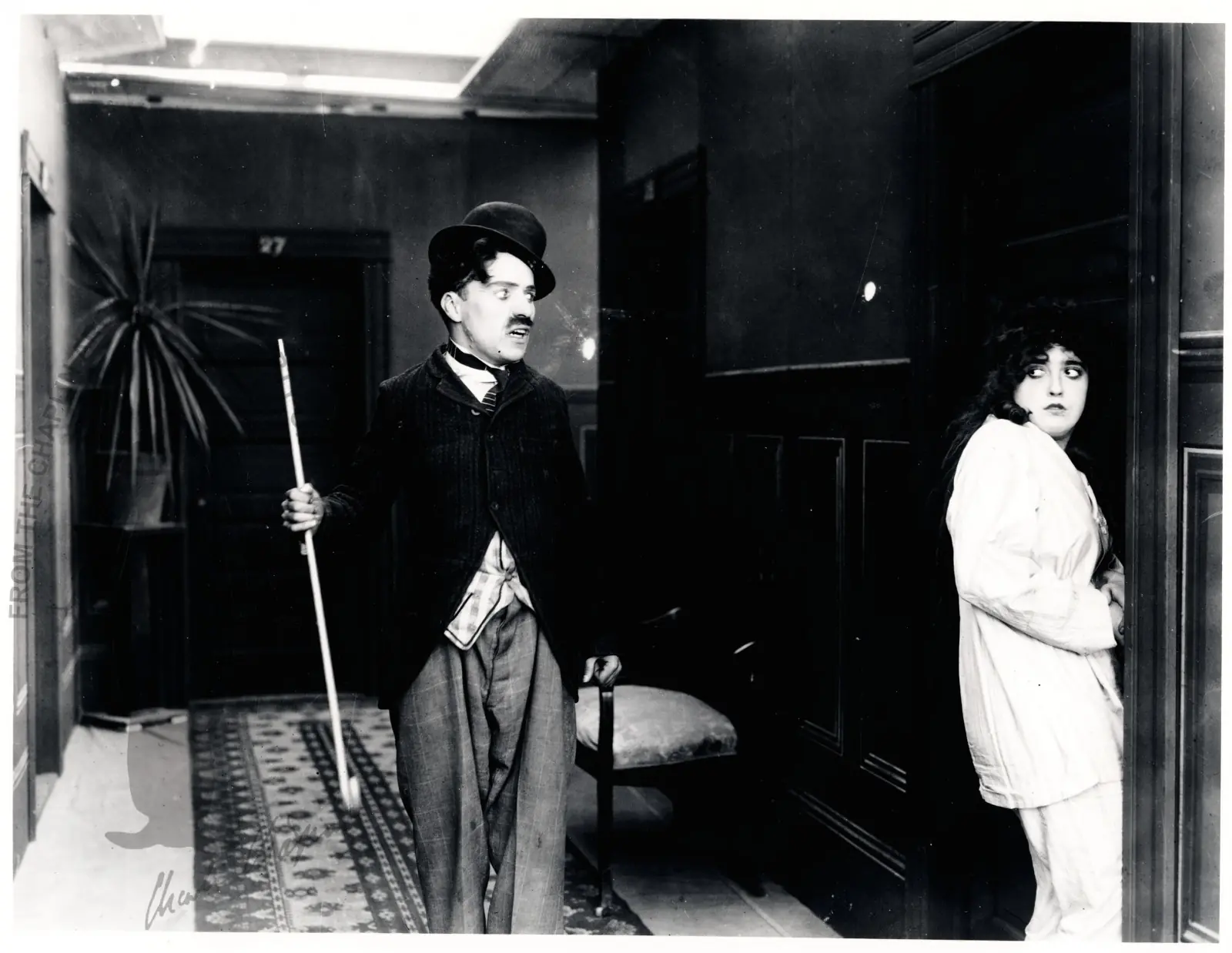

His film debut was in Making a Living, where he played a petty swindler and thief, who in the final part of the film had to face the iconic Keystone Cops, an eccentric group of policemen. Chaplin’s negative character was contrasted with the decency of the main protagonist, played by the film’s director, Henry Lehrman. Although Sennett wasn’t pleased with Chaplin’s first performance, accusing him of lacking comedic talent (similar to Fred Karno’s earlier critique), the press and public responded positively. The next two films were released almost simultaneously. Filming for Mabel’s Strange Predicament began earlier, but due to the simpler nature of the footage, Kid Auto Races at Venice hit theaters two days earlier on February 7, 1914. Chronology is important here because it was in these films that audiences first encountered Chaplin’s iconic alter ego, the Tramp. In his autobiography, Chaplin recalled that the character was created specifically for the film with Mabel Normand, Keystone’s biggest female star, in the lead role. He described the birth of the Tramp as follows:

On my way to the dressing room, I thought I’d wear baggy pants, oversized shoes, carry a cane, and wear a bowler hat. I wanted everything to be a contradiction: the pants should be baggy, the coat tight, the hat small, and the shoes too large. I couldn’t decide whether to appear older or younger, but I remembered that Sennett wanted me to play an older man, hence the small mustache, which I figured would age me without hiding my expression. I didn’t know who my character was, but the moment I dressed up and finished my makeup, I felt I knew him well. The moment I stepped onto the set, the Tramp was born. [Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography]

Both Mabel’s Strange Predicament and Kid Auto Races at Venice, the latter being largely improvised during a real children’s race, offer evidence of Chaplin’s words. Although the Tramp would evolve over the years, his debut already highlighted the key characteristics of the character. His mismatched, odd attire reflected his inability to fit into the surrounding world, but also his desperate desire to find his place in it—after all, it consisted of seemingly elegant elements like the cane and bowler hat. Under Sennett’s direction, the melancholic aspects of the Tramp’s nature couldn’t fully develop, as the studio’s productions followed a less ambitious style. However, Chaplin treated this period as a learning experience, bringing him closer to his ultimate goal—writing, directing, and producing his own films, in which he would play the lead roles.

Initially, Sennett refused to let Chaplin direct or even give him a proper place on the posters (the actor wasn’t yet popular enough to “waste ink on him”). After several productions, Sennett finally allowed Chaplin to direct his next film, Caught in the Rain, on the condition that Chaplin would reimburse him $1,500 if the film flopped (Chaplin’s monthly salary was $150). Caught in the Rain clearly stood out from a typical Sennett production. Its pace was slower, with more emphasis on the story and characters. While it wasn’t a huge leap in quality, the success of Chaplin’s directorial debut earned him the green light for future projects and significantly increased his popularity, leading to the formation of a growing audience that embraced Chaplin’s vision of comedy. Thus began a gradual shift away from entertainment focused solely on action and gags toward a form of comedy that retained slapstick elements but also acknowledged the emotions and experiences of its characters.

After Caught in the Rain, Chaplin wrote and directed nearly every Keystone film in which he starred. The exception was Tillie’s Punctured Romance, which went down in cinema history as the first feature-length comedy. Depending on the version/restoration, the film’s length ranges from seventy to eighty-two minutes, an unimaginable length at the time when a standard comedy was usually only a few minutes long. The title role of Tillie was played by Marie Dressler, who was about fifty years old at the time. The film’s humor largely relied on the fact that Dressler, who looked more than mature, played the role of an innocent, flirtatious girl with the emotional maturity of a young adolescent. Chaplin’s character, drawn to Tillie’s wealth, attempts to seduce her and maneuver in such a way as to leave with a vast dowry. Although Chaplin and his on-screen partner, Mabel Normand, had roles that were nearly equal to Dressler’s, Keystone nearly omitted their names from the promotional campaign. This was indicative of the time—Dressler was a well-known and beloved star of Broadway theater and operetta, considered “real” art.

Cinema, at the time, was viewed as mere carnival entertainment, something for the masses. It would take many years and the creation of thousands of films—including those that contributed to the elevation of cinema as an art form—to change this perception. Among them, of course, are Chaplin’s films, which will be discussed in the subsequent parts of this series dedicated to his work.

To be continued in Vol. 2.