IN TIME AND SPACE. 10 historical movies from ten countries

Every country has its own history, recorded in the annals or handed down from generation to generation. Therefore, historical cinema is a universal genre, practiced wherever cinematography develops. The belonging of specific films to this genre seems obvious on the surface, but nevertheless often raises doubts. They arise due to excessive deviations from what we know about history from textbooks. Old chronicles and archaeological research explain a lot, but will not create a complete picture of past reality. Directors often use historical materials in order to tell a fictional storyline, usually an adventure-romance one. They have the right to do so, but if they make a centuries-old historical event an important factor in the performance, there is no reason not to include it in the genre. Deviations from the “truth” are not always mistakes of the creators, as they often serve specific purposes – they are the result of budget, convenience, specificity, creativity….

7. The Deluge (Potop; Poland 1974), dir. by Jerzy Hoffman

The Poles also have their own film epic. And more than one. The first is Knights of the Teutonic Order (1960) by Aleksander Ford, the second is Pharaoh (1966) by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, which, however, I didn’t consider because it doesn’t tell the story of Polish history (if it does, it’s about modern Poland, but in a metaphorical way). Before I get to the point, I will mention two more films that were made on a smaller scale, so many people may not remember them. First of all, Mountains in Flames (1955) by Jan Batory and Henryk Hechtkopf, which is the first colorful historical production shot in Poland. It treats of a revolt of peasants against the nobility in 1651. The leader of the uprising was Aleksander Kostka-Napierski, who in the film utters these words: “You accuse me of betrayal of the homeland. You, who bring this homeland to its downfall. You have seized everything for yourselves, and the whole nation lives in slavery and misery. What right, then, do you call the just struggle of the people for freedom and life a godless rebellion”. Such a statement can be understood ambiguously, including as an expression of opposition to the system then prevailing after the war. Even if the film was made to the order of the authorities of the time, the communist propaganda contained in it no longer offends today, and the film defends itself by showing the realities of the era and efficient production.

Another Polish film of the genre worth mentioning is titled King Boleslaus the Bold (1971), directed by Witold Lesiewicz. It’s an interesting biography of one of the most famous Polish kings, realized with attention to detail… But let’s move on to the title that appears in the headline, because it’s the one I wanted to write more about, even though a lot has been written about it anyway. Why did I choose The Deluge? Because it fits the most in this list, since, like the rest of the titles placed here, it’s a model of epic cinema and a leading entry in the country where the director comes from. Therefore, it can be shown abroad without shame, watching the amazed faces of the audience.

Jerzy Hoffman’s previous work Colonel Wolodyjowski (1969) seems next to this film a mere exercise before taking on the real challenge. Hoffman, being an aficionado of the Sienkiewicz trilogy, set aside for the time being With Fire and Sword, which had already been filmed in Italy (1962) with a highly mediocre result, even by the standards of Italian peplum. Based on the 1886 literary work, the director – together with Adam Kersten and Wojciech Żukrowski – prepared the text, creating the basis for a passionate show. The Swedish aggression in 1655 wrote one of the bloodiest pages in Poland’s history – this subject deserved careful staging and an impressive setting. The film was shot over 535 shooting days in Polish and Soviet locations, and the budget amounted to 100 million PLN (by comparison, the making of Knights of the Teutonic Order consumed 38 million, Colonel Wolodyjowski – 40, and Pharaoh – 60).

The plot contains elements of a swashbuckler film style adventure romance. This is indicated not only by an emotional plot and a sabre duel in the rain, but also by intrigue with a change of identity, as in The Hunchback (1857) by Paul Féval and The Count of Monte Cristo (1844) by Alexandre Dumas (the change of identity in The Deluge, however, serves a purpose other than revenge – it serves to redeem guilt, to tarnish the stigma of a traitor). There’s a lot of exciting adventure here that leads to the reunion of two charismatic characters. But focusing on a pair of fictional characters, Kmicic and Oleńka, didn’t at all diminish the importance of the picture – the historical background, the intrigues of the magnates and the war going on around them remain a very important factor, shaping the personality of the hero, influencing his fate. It’s difficult to find appropriate words of appreciation for the numerous actors who took part in the production. It’s difficult to have reservations about the battle scenes – they are impressive as few in Polish cinematography. The five-hour screening doesn’t prove to be a tiresome experience, on the contrary – it promises a long, delicious feast.

8. 80 Hussars (80 huszár; Hungary 1978), dir. by Sándor Sára

“Why in history does the spirit of rebellion always return?” – asks one of the characters rhetorically. The hottest – due to revolutions – period in history dates back to 1848 and is called the Springtime of Nations. At that time, rebellions against despotic rulers broke out almost all over Europe. The Kingdom of Hungary was under the rule of the German Habsburg dynasty. The film tells the story of a group of eighty hussars who revolt against their Austrian superiors. After being ordered to whip out a comrade-in-arms for desertion, they make a joint decision that will cost them dearly. Stationed on Polish soil, the Magyars intend – against the orders of their commanders – to return to their own country, to their own homes, to their waiting families. The Hungarians had their own country, unlike the Poles, who were wiped off the map – there is, by the way, a beautiful scene in Sándor Sára’s film in which the Poles sing the national anthem (Poland Is Not Yet Lost). Much of the footage was shot in Tarnow and the Tatra National Park.

This is one of those films in which not only human suffering is visible, but also that of animals. Crossing the river, mountains and stones must have been difficult and dangerous especially for the horses, which were not spared here. It affects the emotions very much, grabs the heart and puts you in a stupor. The director probably achieved the effect he wanted. It’s difficult to pass by this film indifferently, and for Hungarian cinematography it’s a unique work. All the more surprising that it’s usually overlooked in professional studies of cinema history. Timeless themes that often recur in discussions, such as patriotism, the courage to rebel, determination to pursue one’s goals, and independence and the associated comfort of having one’s own state, have here become part of an exciting historical-adventure story. The pessimistic pronunciation of the work was perfectly reinforced by the majestic mountain scenery, beautiful and unflinching in the face of convoluted human fate.

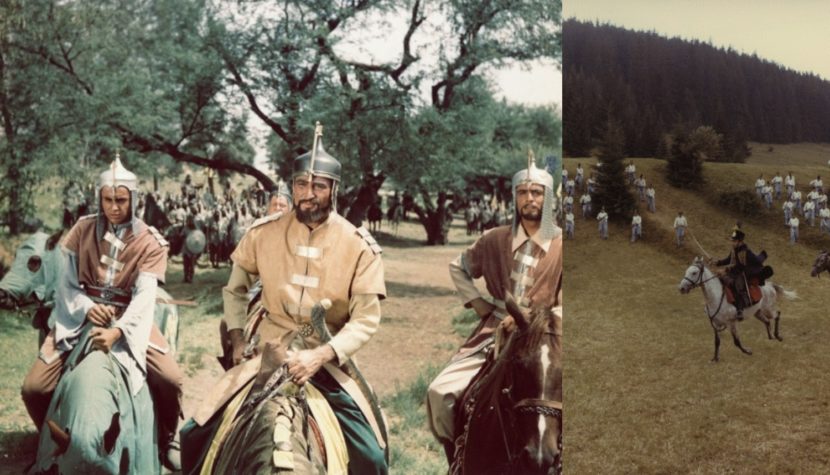

9. Khan Asparuh (Хан Аспарух; Bulgaria 1981), dir. by Ludmil Staikov

One of the biggest box office hits of Bulgarian cinema is Metodi Andonov’s moving drama The Goat Horn (1972), with the wonderful Katya Paskaleva in a dual role. The plot is set in 17th century Bulgaria under the Turkish yoke. However, the historical background gives way to a story about blind hatred that leads to nothing. About revenge that destroys the dream of a better future. Such a plot can be transferred with equal success to other realities, so among Bulgarian historical films the more representative work is Khan Asparuh, directed by Ludmil Staikov. The film was made to commemorate the 1300th anniversary of the Bulgarian state, but also to prove that a monumental historical production can be made in this country. It lasts about 320 minutes and is divided into three parts reflecting the three stages of the state’s creation: Phanagoria, The Migration and Land Forever.

“History is not the past, but what we know about the past”, says Byzantine Emperor Constantine IV to Belisarius, who befriended these “barbarians.” His point of view is taken by the scriptwriter (and researcher of the history of Bulgarian lands), Vera Mutafchiyeva, as she recounts the birth of her homeland. Located in what is now Ukraine, Phanagoria is an ancient city that was the former seat of the Bulgarian nation. Harassed by the Khazars, the inhabitants decided to look for another land to live in. It’s possible that many countries, not just Bulgaria, were founded in the way shown in the film. A lot of work went into this project. Thanks to a huge amount of money, wonderful mass and battle scenes were realized. Never before or since has such a large-scale production been created in this country. The end result is admirable. In 1984, a 90-minute long version was made for the international market. It was titled 681 AD: The Glory of Khan and English dubbing was added. In such a shortened and re-edited version, the film loses most of its qualities. The Deluge, too, in the original is about 300 minutes long. Can you imagine that the remake, shortened to 90 minutes, could match the original?

10. Queen Margot (La reine Margot; France 1994), dir. by Patrice Chéreau

The film is a French-Italian-German co-production made with the American Miramax studio, but the role of the French is dominant. It was in the country on the Seine that a page of history was written in blood with the date August 23-24, 1572. And it was two Frenchmen who made the best use of this page, creating something of absolute value based on it. The first was writer Alexandre Dumas, the second was director Patrice Chéreau, who shot his film almost entirely in France, casting most of the roles with actors from that country. Queen Margot is a mature and intense production that penetrates inside and strikes sensitive chords. The authors took care of the suggestiveness of the picture. In the 1990s, the exquisite style of costume romances and swashbuckler productions, so clearly rooted in the French film tradition, had not yet passed away – as evidenced by the films Revenge of the Musketeers (a.k.a. D’Artagnan’s Daughter, 1994) and On Guard (1997) – but Patrice Chéreau didn’t go that route. His concept was right – such a tragic and bloody moment in history deserves a more mature approach.

The strength of the film lies in the atmosphere, extremely gloomy and harsh, which co-create a decadent vision of a world full of people with a dark nature, thirsty for blood, possessed of a morbid fanaticism and thirst for power. It manages to bring to the surface the true horror of the era. This is not a boring lecture on history, but a cinema full of emotions. Emotions that aren’t expected from a typical entertainment production, but from a film drama that is ambitious and painful in its message. Passions and wariness come out of people at the least expected moments, contributing to a great tragedy. On the screen, this is presented believably, without embellishment or exaggerated effect. Realism simply strikes between the eyes. Also thanks to the actors. Isabelle Adjani in the title role is superb, but the supporting cast – led by Virna Lisi – is phenomenal as well. This is also due to a well-crafted script. Interestingly, the author of the text is comedy specialist Danièle Thompson, daughter of Gérard Oury and co-writer of his best films.