IN TIME AND SPACE. 10 historical movies from ten countries

Every country has its own history, recorded in the annals or handed down from generation to generation. Therefore, historical cinema is a universal genre, practiced wherever cinematography develops. The belonging of specific films to this genre seems obvious on the surface, but nevertheless often raises doubts. They arise due to excessive deviations from what we know about history from textbooks. Old chronicles and archaeological research explain a lot, but will not create a complete picture of past reality. Directors often use historical materials in order to tell a fictional storyline, usually an adventure-romance one. They have the right to do so, but if they make a centuries-old historical event an important factor in the performance, there is no reason not to include it in the genre. Deviations from the “truth” are not always mistakes of the creators, as they often serve specific purposes – they are the result of budget, convenience, specificity, creativity….

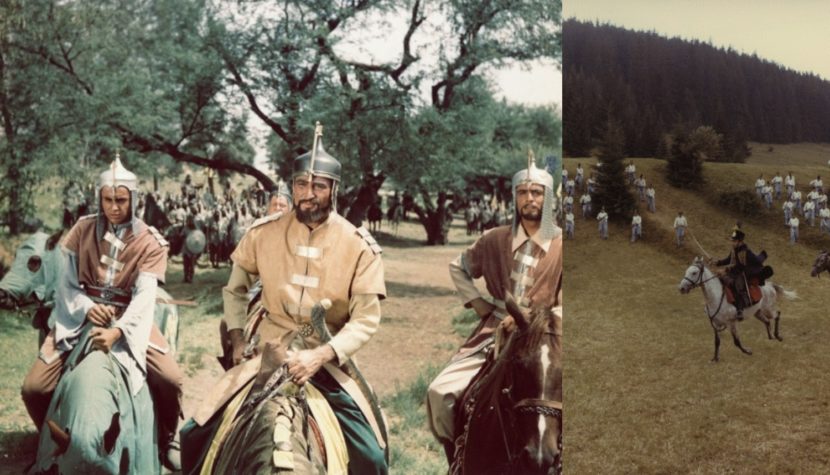

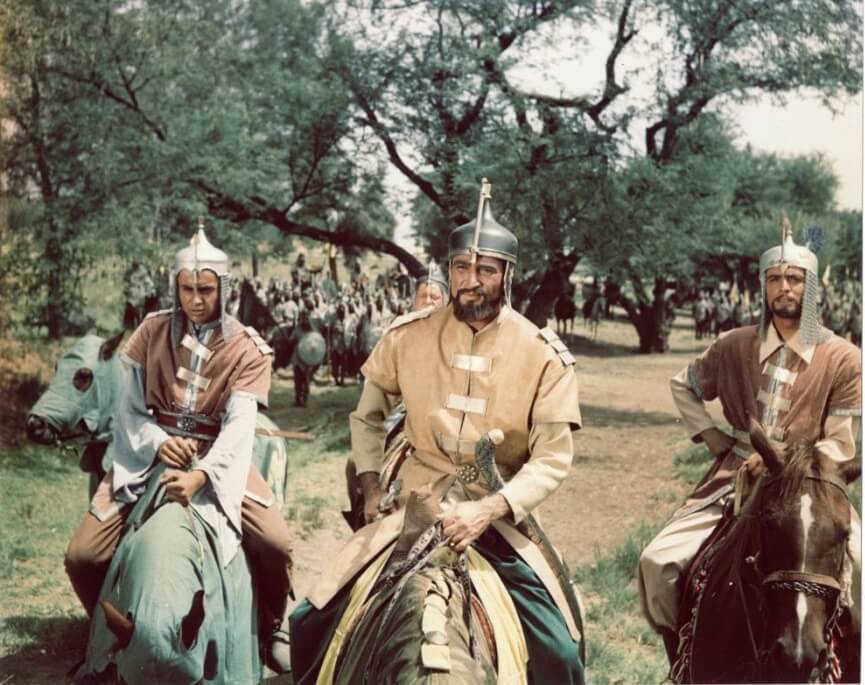

4. Saladin and the Great Crusades (El Naser Salah el Dine; Egypt 1963), dir. by Youssef Chahine

The first Egyptian superproduction, made along the lines of the Western events of the season. A colorful biography of the Sultan of Egypt, seasoned with a handful of melodrama, reminding us of the religious wars in grand style. The script was based on a novel by Najib Mahfuz, later a Nobel laureate who also wrote film scripts. The story is set during the Third Crusade (1189-1192), commanded by three European monarchs: Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, French King Philip II Augustus and English ruler Richard the Lionheart. The juxtaposition of Saladin and Richard comes off well, indicating emphatically that the director was not biased, and presented both superiors with respect, while emphasizing the pacifist message. Crusaders or Arabs – all corpses look the same. For what ideas do they make the sacrifice? For power, glory and personal gain of the commanders. Because, after all, not for God. “Those who use the cross as an excuse to invade my land aren’t my brothers”, these words are spoken by an Arab who is… a Christian.

Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine studied acting in Los Angeles. So he observed firsthand what was going on in Hollywood, but also became more familiar with the mentality of Christian America. And while he made sure to include extraordinarily impressive battle scenes in his film, he didn’t forget the ideological message of tolerance, respect and absolute honesty. Although Egyptian cinema is made mainly for the domestic market, this film can confidently conquer the world because no foul play has been cast. Every aspect of the film – from the thoughtful script to the technical nuances – is polished. It’s possible that Chahine – who is also a producer – drew handfuls from Italian productions called peplum, as composer Angelo Francesco Lavagnino was hired.

Saladin and the Great Crusades is a high-class endeavor, which for European or American viewers is an exotic production, but one that clearly conveys universal content. “Knights of the cross” and “knights of the crescent” have not yet buried their swords – this crusade is still going on, so the message of mutual acceptance and respect for the other is still relevant. The film also encourages you to delve into the era and try to understand its laws, specifics and atmosphere.

5. Samurai Banners (Fûrin kazan; Japan 1969), dir. by Hiroshi Inagaki

“Swift as the wind, gentle as the forest, passionate as the fire, unshakeable as the mountain” – this is the Takeda clan’s motto, inscribed on the banners. It’s taken from Sun Tsu’s The Art of War, dating back to the 6th century BC. Samurai Banners is a film in which war strategy and tactics are very important, so the film is closer to a historical production than a classic samurai story. The plot spans three eras during the Sengoku period, focusing on the life and career of prominent Japanese strategist Kansuke Yamamoto. We first get to know him as a ronin, then as a general of extraordinary ambition and imagination. The film moves smoothly from one event to the next, thoroughly presenting a picture of those times, carefully revealing the various pages of history. Events culminate in the fourth battle on the Kawanakajima Plain in 1561, which went down in history as the bloodiest.

Japan’s historical annals hide many inspiring episodes, so it should come as no surprise that many domestic directors have tried to reckon with the feudal past in their films. But, for example, plots from Akira Kurosawa’s films can be freely transferred to other realities, because they are universal. The situation is different with Hiroshi Inagaki’s films. His excellent works, such as the three movies about Musashi Miyamoto (Samurai Trilogy, 1954-1956), Daredevil in the Castle (1961) or, for example, Chushingura: The Loyal 47 Ronin (1962), are set in a specific reality and cannot be easily transferred. Therefore, in the historical drama category, Inagaki is, in my opinion, the most representative Japanese filmmaker. Samurai Banners is one of the last films of this great director. An excellent performance was created in it by Toshirô Mifune – tough and confident in scenes with men, but a bit dim in scenes with women. In addition – good roles by Yoshiko Sakuma as Princess Yu and Kinnosuke Nakamura as daimyō Takeda.

I would like to point out one more thing. Watching European historical films, I noticed that horses are treated terribly in battle scenes (and not only). The parts involving them look disturbing. Samurai films are more subtle in this regard despite the noisy and violent style of this type of production. The Japanese, led by Inagaki, used mounts for riding, but they were spared in the stunt scenes. Such an approach can cause disappointment, as it senses a not very high degree of credibility. I see it differently – the film gets an extra point from me for the fact that for the sake of art and entertainment, the lives of animals were not risked. Horses, by the way, are underestimated but essential actors of historical cinema. And this is often forgotten.

6. Michael the Brave / The Last Crusade (Mihai Viteazul; Romania 1970), dir. by Sergiu Nicolaescu

Sergiu Nicolaescu entered the film industry with momentum. His directorial debut was the impressive historical production The Dacians (1966), but it’s his second work, Michael the Brave, that is the most watched Romanian film worldwide. A great figure worthy of a great film. A man who fought fierce battles against the Turks. The success of Nicolaescu’s previous film made the Americans want to co-finance the director’s next project. They proposed casting a Charlton Heston or Richard Burton-type star in the role of Michael the Brave. However, the Romanian authorities headed by Nicolae Ceaușescu opted for a local actor to play the Romanian national hero. It just so happened that the director was also an actor, so it was he who was selected to play the main character, but he preferred the role of the vizier Selim Pasha for himself. The title character, on the other hand, was played by Amza Pellea, a respected theater actor who already had experience playing great chiefs. He twice played the last Dacian king, Decebal, in films: The Dacians (1966) and Trajan’s Column (1968).

The film about Mihai Pătrașcu outlined an interesting relationship between the characters. After all, the brave leader was friends with those with whom he fought: Selim Pasha and Sigismund Báthory. His motivation is clear – only the country of his ancestors matters. This attachment to his roots compels him to fight for three principalities: Wallachia, Transylvania and Moldavia. What first strikes you while watching the film is the mass of work done on the battle sequences. I would venture to say that we have here the best battle scenes ever filmed. But the smaller skirmishes, such as the chivalric duel between the Wallachian hospodar and the Transylvanian prince, also add to the viewer’s interest. The actors have been superbly cast, and Titus Popovici’s script is an expert job, the hallmark of a brilliant strategist. I also paid attention to the beautiful music (Tiberiu Olah) – it brings back nostalgic memories. The duration of the film is two hundred minutes – it passes without a moment’s boredom.