THE 400 BLOWS. François Truffaut’s Masterpiece Explained

And despite the distress caused by some newspapers printing various foolish things, I absolutely do not regret making this film. I knew it would cause you a lot of worries, but I don’t care: since Bazin’s death, I no longer have parents.

The Unloved Child

Antoine, without a doubt, does not have a happy childhood. He is an unloved child—one who feels unwanted. His parents (especially his mother) largely treat him like an object—an obstacle blocking their path. Just listen to their conversations (or rather, arguments). In these discussions, Doinel often functions as a “bargaining chip,” tossed between parents. For instance, the mother threatens, If you can’t stand him, say so; he’ll be sent to the Jesuits or the cadets! At another time, the father asks during a meal, What should we do with him for the holidays? Antoine is not treated by his parents as a person but as an object to be sent away or left somewhere.

An exception to the rule is the family outing to the cinema—the only part of The 400 Blows where the Doinel family functions properly. Leaving the cinema, all three laugh loudly. The stepfather and mother walk on the sides, with Antoine in the middle, holding both parents’ hands—symbolically uniting a family usually broken. Truffaut proves in this scene that understanding between these characters is possible, but only on a proper plane—such as the cinema. The choice of film that the Doinels go to see is significant—Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us. By sending the characters to the debut of a friend, one of the most important creators of the French New Wave, and then demonstratively showing their satisfaction with the shared experience, Truffaut seems to say: Only the films we create—as ‘real cinema’—will restore harmony to your life.

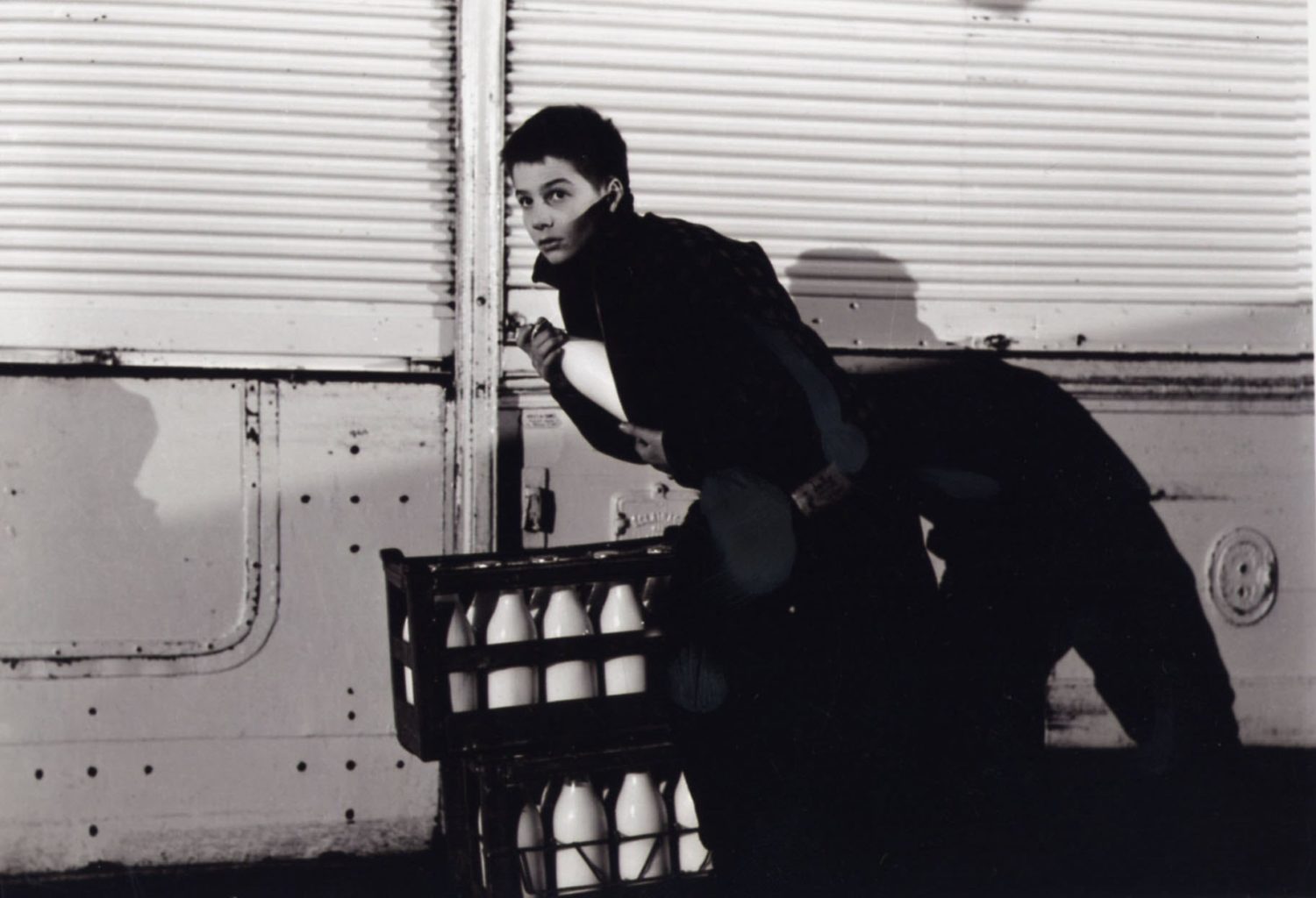

Unfortunately, such a positive experience is just a small drop in the ocean of the Doinels’ indifference. Daily, Antoine is forced to seek love and acceptance elsewhere than home. The protagonist finds these values in friendship—René is a faithful companion whom the boy can always rely on. Their shared experiences are often accompanied by a cheerful musical leitmotif, clearly indicating the joyful, carefree nature of these scenes. Antoine is truly happy in the company of his friend. The second “character” with whom Doinel seeks solace is Paris. How important the capital of France is to Truffaut’s debut is shown by the film’s prologue, during which the opening credits appear on the screen. It consists of relatively short shots of Parisian streets, with the Eiffel Tower always in the background. This iconic landmark, due to its recognizable character, quickly orients the viewer to the film’s setting and hints: Pay attention to the location. Indeed, as the plot develops, Paris begins to play a significant role in the protagonist’s life, becoming a kind of surrogate mother for Antoine. The city provides Doinel with food (the scene of milk theft is particularly telling, as the milk takes on a symbolic, “maternal” character), shelter, a sense of security, and, last but not least, entertainment.

Rebel

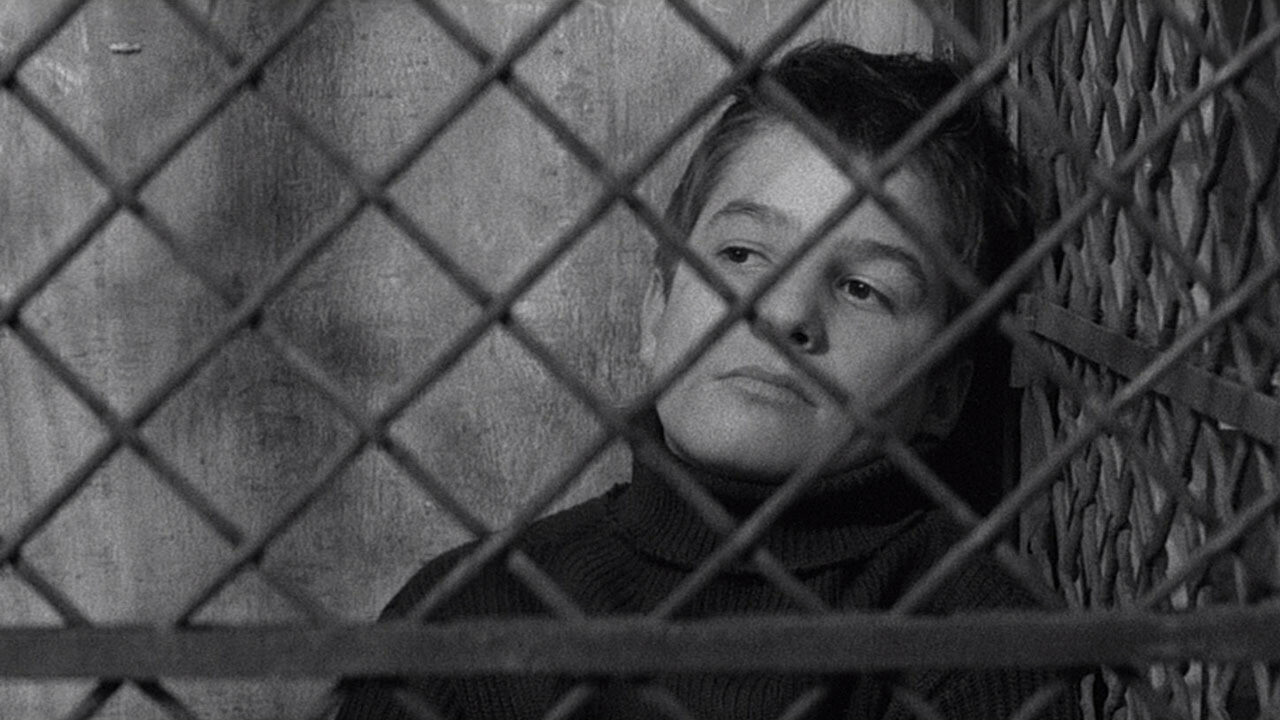

Antoine is also a rebel—not without reason and not by choice. The reality he faces, which, to put it mildly, is not optimistic, forces him into rebellion. The most characteristic signs of Antoine’s rebellion are, unsurprisingly, his escapes. Throughout the film, Doinel decides to run away three times—twice from home and once from the juvenile detention center. However, it is only the last escape that proves truly liberating. The camera follows the protagonist running toward freedom for an exceptionally long time—the shot lasts exactly 80 seconds! Truffaut emphasizes the significance of this scene, giving it a symbolic, almost mystical character. He forgoes music, and in the background, only the sounds of nature and the steady rhythm of Antoine’s footsteps can be heard—each step bringing him closer to the freedom he longs for. Eventually, the protagonist reaches the sea, on the beach where his journey ends. The final shot of The 400 Blows is a freeze-frame showing the protagonist’s face—a boy who may have experienced true freedom for the first time in his life and now, with the initial emotions having settled, is unsure of what to make of this new feeling.

Antoine’s rebellious nature is signified not only by his actions but also by his clothing. It’s worth noting that the insulated jacket the protagonist wears during his nighttime escapade through Paris closely resembles the jacket worn by the American icon of rebellion in On the Waterfront. Marlon Brando, in this case, played Terry Malloy—a former boxer who, throughout the film, undergoes a transformation, gains self-awareness, and decides to stand up against a powerful local gangster. There is no doubt that Truffaut, a great film enthusiast and active film journalist, had seen On the Waterfront—one can assume that Doinel’s jacket is a conscious reference to Kazan’s work, whose films the French director held in high esteem, further emphasizing the rebellious nature of the protagonist.

It is also worth mentioning the generation to which Antoine Doinel belongs—a generation that took to the streets in May 1968, initiating a wave of demonstrations across almost the entire country. The riots were sparked by students who, a decade earlier (around 1958—the date of Truffaut’s debut film’s production and setting), were roughly Doinel’s age. Considering this, the contemptuous rhetorical question posed by the teacher, irritated by the students’ behavior during the first classroom scene, seems almost prophetic: What will become of France in 10 years?

Artist

An unloved child, a rebel, but also an artist. Antoine’s childhood is the childhood of a future creator (who, in an unspecified future, might create an autobiographical film about his own youth). This is already hinted at by Doinel’s early interests, as he seeks refuge from his bleak everyday life in the cinema, visiting it three times over the course of the film (it’s worth remembering that The 400 Blows spans just a week)! Where does he get the money for this? From his parents, of course—he pays for movie tickets with change intended for the school cafeteria.

The second, equally important, if not more important, passion of Antoine’s is literature. The most vivid sign of this interest is Doinel’s absorption in Balzac. Truffaut staged this scene in a rather peculiar way—an anonymous voice (perhaps in Antoine’s mind, a sort of imitation of Balzac’s voice) can be heard off-screen, reading the ending of The Quest of the Absolute, while the camera focuses on the protagonist. One can easily see the expression of great pleasure on his face. Inspired by Balzac’s work, Doinel constructs a shrine dedicated to the author of The Human Comedy in the next scene and then resorts to plagiarizing The Quest of the Absolute while writing a school essay. Other manifestations of Antoine’s passion include small creative acts—attempting to forge his mother’s handwriting and the well-written letter he leaves for his parents, informing them of his first escape from home.

In subsequent installments of the series, Antoine will pursue his passion for literature and his artistic ambitions, working on his debut autobiographical novel—in Bed and Board, he will still be writing it, and only in Love on the Run will he complete and publish it. This will allow Doinel to do what Truffaut largely accomplished with The 400 Blows—finally come to terms with his traumatic past, conducting a form of self-therapy through art. It is no coincidence that the director ended the aforementioned letter to his father with the words: You mockingly say in your letter that I came back from Cannes finally liberated from my numerous complexes. You have no idea how right you are: for the past two months, I have felt that I have rid myself of an old nightmare and that, as a result, I have become a man capable of raising a child.