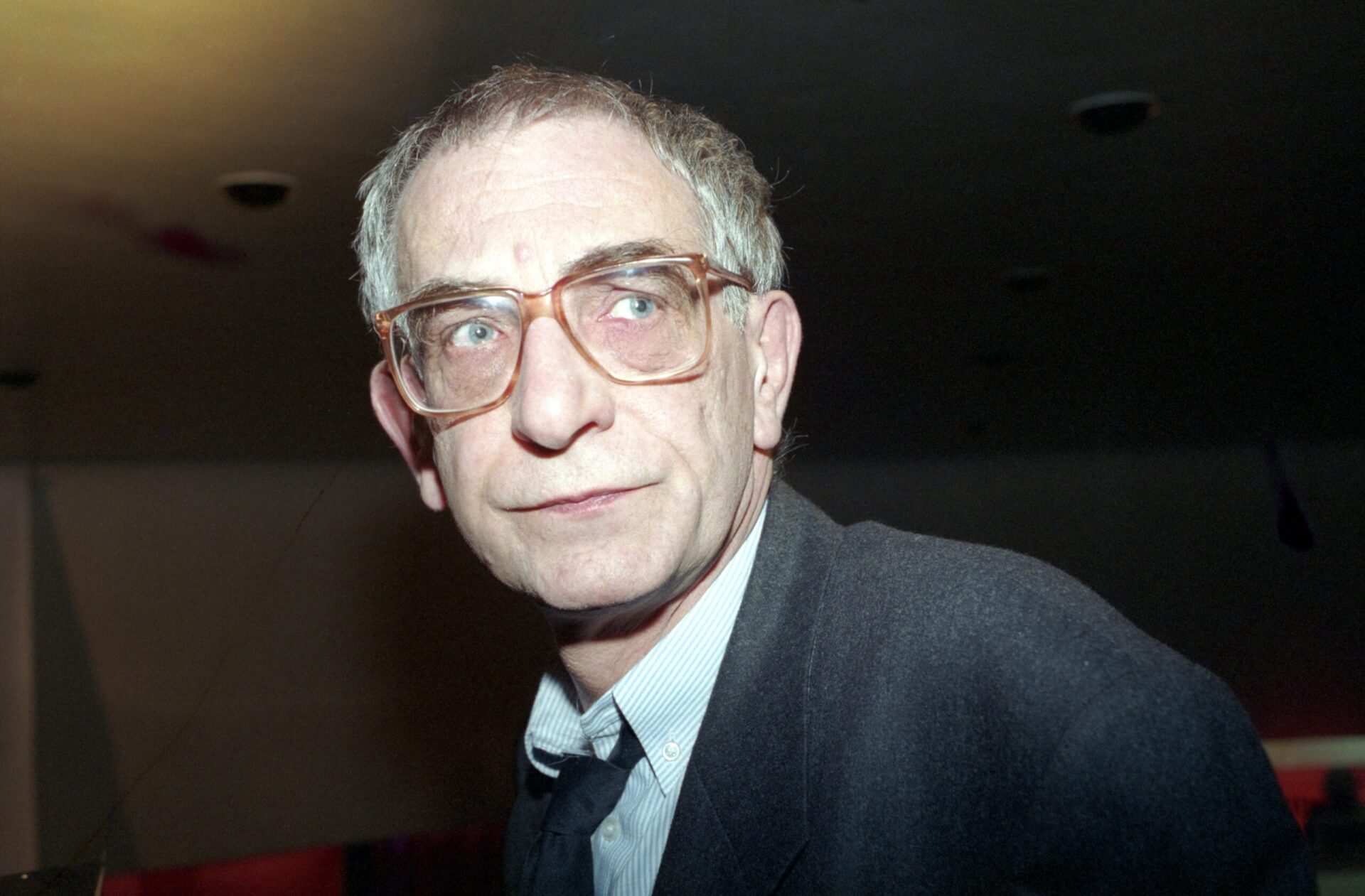

Everything There Is to Know About Krzysztof Kieślowski ‘s Cinema

…- a remarkable work, one of the most significant in the extensive filmography of this director, and certainly a standout in Polish cinema overall. On this occasion, we revisit Kieślowski’s film legacy, starting from his student short films, through documentaries, to cinematic classics.

His beginnings certainly did not foreshadow such an outstanding film career. It all started with dreams of becoming a theater director, influenced by Kieślowski ‘s time at the Theatre Technical High School, where he was captivated by the quality of Polish performances, which, in his later opinion, were fantastic between 1958 and 1962. The only problem was that to start a career as a theater director, one had to complete some higher education first. However, the solution turned out to be very simple—there were many possibilities, but he thought: why not choose film directing as a path to theater directing? Both involve directing. However, the Łódź Film School did not welcome Krzysztof with open arms—quite the opposite. Twice in a row, the admissions committee rejected his attempts.

Kieślowski had practically given up on his dreams of a career as a theater director, but his ambitious (and fortunately so) and sensitive nature, which I consider a characteristic strongly reflected in his work and will refer to multiple times, compelled him to prove that he would get into the School anyway. And he did. I will explain this sensitivity by recalling an episode from the life of the young Krzysztof—In June 1963, he took the film school entrance exams for the second time and reached the final phase again. He didn’t get accepted. He returned from Łódź to Warsaw and met his mother at the moving stairs of the W-Z route. He didn’t have to say anything. She looked at him and burst into tears. I promised myself then that it would never happen again. Fortunately, the third time was a success. Someone might know why it worked out that time, but Krzysztof himself comments on it very simply—I don’t think they should have accepted me. I was a complete idiot. I can’t understand why they accepted me. Probably because I applied three times. Kieślowski’s film career developed exceptionally vigorously; his body of work, which includes both shorts and feature films, documentaries, and fiction, counts nearly fifty films.

Although the director’s filmography opens with the narrative short film Tramway (1966) created at the National Film School in Łódź (TV addition came later), which didn’t impress the examiners and received only a 3+ grade and the label of being average, his early work was dominated by documentaries. The poetics of these documentaries, based on the observation of everyday life and a thorough analysis of encountered characters, attitudes, and dramas, permeate his (especially later) fictional films.

At the National Film School in Łódź, he created two more shorts—a documentary The Office (1966), exposing the bureaucracy of the Social Insurance Institution, and a narrative short with a predominantly documentary handheld camera style— Concert of Requests (1967), a reflection on the behavior and attitudes of young people, with a musical background rich in catchy and iconic tunes like Dwudziestolatki, Nigdy więcej or Trzynastego.

Right after graduating from film school, Kieślowski made his first (though not last) film for television—The Photograph (1968). The inspiration for it was a photograph he received from one of Poland’s greatest documentarians, Kazimierz Karabasz, depicting two small boys with rifles. Years later, Kieślowski found the now-adult subjects of the photo and made a conversation with them the topic of his next documentary film. The young and still inexperienced director used a method in this film that he then considered right but soon realized was not and never used again—a dispassionate observation and filming of life as it unfolds, without considering that someone’s privacy might be violated.

However, Kieślowski stayed with the documentary film trend for a while. He began collaborating with the Documentary Film Studio (where he had previously done student internships) and made eight films there between 1969 and 1973, mostly short films (with one exception—the approximately 45-minute film Workers ’71: Nothing About Us Without Us, co-directed by Tomasz Zygadło). During this time, Kieślowski also made a sixteen-minute documentary for the Film Studio Czołówka—I Was a Soldier, about soldiers who lost their sight during World War II.

Returning to Krzysztof’s collaboration with the Documentary Film Studio (WFD), its first result was Kieślowski’s graduation film From the City of Łódź (1969), in which he wanted to showcase what he considered the picturesque city he knew well, along with its residents and all their daily worries, concerns, and dramas. It was an authentic depiction of the reality surrounding him, observed daily. He explained his intention as follows: “I want to seek the non-newspaper truth, to contrast everyday reasons with those presented in the newspapers. There will be no exoticism here—no criminals, no outcasts, no dens. Everyday life and ordinariness are exotic enough.”

A rather typical documentary, Factory (1970), rightly awarded in 1971 for being the film most engaged with social issues, as the title suggests, depicts a day on the shop floor in a tractor factory. It shows the feeling of the employers’ soullessness and the inhumane working conditions, making it Kieślowski’s first work stopped by censorship.

The next film, Before the Rally (1971), fortunately did not have these problems due to its relatively entertaining and neutral topic. It tells the story of driver Krzysztof Komornicki’s preparations for the Monte Carlo rally and his struggles with the iconic Polish Fiat. However, the director did not consider the report successful.

The aforementioned longest film from this period (1969-1973), Workers ’71: Nothing About Us Without Us (1971), is, as Kieślowski himself says, “the most political of my films,” presenting a portrait of workers during that period, more precisely, the state of their minds. It was, of course, stopped by censorship and re-edited by television without the authors’ consent, after which it was broadcast under a different name, The Hosts.

The next entry in Kieślowski’s filmography is a short but poignant and substantial portrayal of the operations of a funeral home, titled Refrain (1972). Perhaps it was frightening at the time it was viewed, but from today’s perspective, the absurdities shown often bring a smile to the viewer’s face. The circumstances of this short film’s creation are interesting. As Witold Stok (cinematographer of Refrain) recalls, Marysia, Krzysztof’s wife, was then heavily pregnant. On the film set, Krzysztof looked at the tombstones and wondered what name to choose for his child. He was convinced it would be a daughter. The gravestones were all marked with 19th-century names like Genowefa, Łucja, and Felicja. He didn’t like them. Maybe I’ll name her Opona (eng. Tyre) (it’s worth mentioning here that Kieślowski had a passion for cars). Opona Kieślowska—that sounds pretty good, he joked. To satisfy the reader’s curiosity, the daughter was ultimately named Marta.

Before his daughter was born, simply wanting to earn money, Krzysztof made two commissioned films—Between Wrocław and Zielona Góra (1972), a promotional-recruitment film encouraging young people to work in industrialized regions, and Basic Safety Procedures in a Copper Mine (1972), an instructional film whose plot is summarized by the title. These works may not be groundbreaking, but they are still by the author featured in this article.

In 1973, Kieślowski made The Bricklayer, whose “plot” is clearly described by Danuta Stok using the director’s words: On May 1st, a bricklayer recalls his past—he advanced to an office job as a young party activist and exemplary work leader. After 1956, disillusioned, he returns to work as a bricklayer. Using the very apt phrase of Prof. Mikołaj Jazdon, this was a portrait of the Sisyphus of the communist world. Unfortunately, the film was once again stopped by censorship and premiered only eight years later, in 1981.

After a series of documentaries, he made another narrative film for Polish Television, also beginning his collaboration with Sławomir Idziak, who would later become the cinematographer for many of his works (such as The Scar, Blue, Decalogue). Kieślowski’s work with the popular playwright Ireneusz Iredyński on his screenplay looked as follows: We met about ten times. Each time was the same. Very early (Iredyński only wrote until noon), early—a bottle of vodka from the freezer. Thick, frozen vodka, and from six in the morning, we drank. We drank, we drank. Until we were completely drunk. At least I was. This is how the half-hour Underpass, the story of a woman who left her husband and job in the provinces and started a new life as a decorator in a shop in the titular Warsaw underpass, came to be.

He then alternated between making films with the Documentary Film Studio and Polish Television. First came a documentary for which Kieślowski promised himself he would win an award. A specific one, but extremely important to the author. It was the award of the Committee for the Fight Against Tuberculosis (granted at the Krakow Film Festival). The film held great sentimental and personal value for him, as it showed tuberculosis patients’ struggles in Sokołowsko, where his father was once treated. Kieślowski was ultimately not completely satisfied with the final result, nor did he receive the award he had aimed for, as it was no longer awarded. However, a film festival, Hommage à Kieślowski, was established in Sokołowsko (https://hommageakieslowski.pl), with the first edition taking place on the 70th anniversary of the director’s birth and the 15th anniversary of his death (in 2011).

The next film was influenced by a paper Kieślowski wrote titled Reality and Documentary Film, in which he posited that one can imagine that every person’s life is a plot. Why invent actions when they exist in life? This text and the idea within it, authored by someone who could only be a keen and patient observer with the aforementioned extraordinary sensitivity, form a foundation for this remarkable director’s work. This assumption is reflected in almost every one of his films.

As a justification for his work, First Love (1974) was created, where the camera follows Jadzia and Romek—a young couple in love—during pregnancy, marriage, and childbirth. Working on the continuation of this documentary, which ultimately was not made, also shows how genuinely good, for this seemingly simple word holds great value, a person Kieślowski was. “(…) thanks to Kieślowski, they got an apartment. He told the TV notables that if they wanted the continuation of First Love to have optimistic accents, the film’s protagonists could not wander around rented quarters. That worked. Krzysztof ensured they had a roof over their heads for the time being.”

A classic blend of fiction and documentary, or in other words, a dramatized documentary that, despite the director’s intervention in the existing reality, turned out to be highly credible, was Curriculum Vitae (1975). This politically tinged work depicts members of the party Control Commission discussing the punishment of one of the party members. The role of the worker was played by the director’s friend Krzysztof Wierzbicki, but the party control commission was authentic. Due to its subject matter, the film sparked heated debates, although the party was satisfied.

Next came the first longer (lasting well over an hour) creation, once again made for television – Personnel (1975). Once again, this is a somewhat personal film based on a piece of the director’s biography, specifically his time at the Theatre Technical High School, where Krzysztof also worked as a wardrobe master. The main character of the film (played by Juliusz Machulski) is a graduate of the aforementioned school and takes his first job as a tailor at the opera. Although it was a fictional film, it was not an abstract, detached-from-reality fiction. Kieślowski’s friend Hanna Krall even says: I watched ‘Personnel’ convinced it was a documentary. Kieślowski simply fooled me, an experienced reporter. The characters chosen by Krzysztof were not random; we could see Irena Lorentowicz, Kieślowski’s set design teacher, three directors (Lengren, Zygadło, Kotek), and tailors from the Wrocław opera. A true elite creating a genuinely artistic world, which, however, disappoints the main character as it turns out to be full of gossip and denunciations.

Another documentary – Hospital (1976) – could be called a work of chance. To get funding for making a film, you naturally had to write a script describing the specific scenes in the film. But how to predict what will happen? One had to improvise and invent, and Kieślowski did it this way: I asked these doctors about various significant, dramatic details they remembered from their professional practice, from their lives, from what they do here with patients, when they put them back together. The doctors told me about things I didn’t know. For instance, that bone surgery requires a hammer. Of course, in normal hospitals, everyone has proper medical hammers. They recalled that in 1954 they had an ordinary hammer, the kind you use to drive nails into the wall, which during a major operation (…) broke. I wrote into the script that there’s an operation, and the hammer breaks. Now it’s time to explain the role and significance of the aforementioned chance. The work on the film proceeded roughly like this: the crew came to the hospital once a week for about 30 hours and filmed. And so for two or three months. It happened that one day, to this hospital, and specifically to the very room where they were filming, the production manager’s aunt was brought in with a broken leg. During the surgery, they used a hammer like the one Kieślowski wrote about in his script. And what happened? (…) the hammer broke – during the shot! So exactly the situation from the script, which should not have happened at all, was repeated. Such a hammer had last broken in 1954. (…) That’s called a documentarian’s luck.

It’s time for another work by the Kieślowski-Idziak duo, their first feature film for the cinema – The Scar (1976). It was also the first Kieślowski film based on a story. The action takes place in the 1960s, between the local community and the workers, there is a conflict caused by the construction of a huge industrial plant in a small town surrounded by forests. The construction manager – director Bednarz (played by Franciszek Pieczka) – cannot withstand the pressure from society and authorities and resigns from his position. Kieślowski was not satisfied with this film, believing it to be poorly made. Firstly, because the script itself was essentially unsuccessful and secondly, he realized it was unfortunately somewhat socialist realist. In the same year, the documentary impression Klaps from the set of The Scar was also made.

An important but secondary role (…) was played in The Scar (…) by Jerzy Stuhr. Kieślowski gave him the face of a non-professional and made him a new, extremely popular figure in Polish cinema. He then wrote the scripts for subsequent films: The Calm and Camera Buff, with Stuhr in mind. In The Calm Stuhr’s character Antoni Gralak, after being released from prison, finds a job at a construction site and wants to start his life anew. He doesn’t want much; he primarily desires peace, a home, and love. Unfortunately, he gets drawn into a conflict between management and workers. According to the director, this film was not political in any sense, it was simply the story of an unfortunate man’s fate, but nevertheless, due to the strike in the background, it was shelved by the authorities for several years.

In the same year (1976), another documentary was made, a sort of confession of a factory director in Lower Silesia who opposed the local party mafia and was destroyed – I Don’t Know (1976). Kieślowski realized while making this film that he could only harm the protagonist. Despite softening it by censoring the names of specific individuals, he believed the risk was too great and that the film should not be shown. It premiered only five years later.

We’ll stay a little longer in the realm of documentary cinema. In 1977, From a Night Porter’s Point of View was created – a portrait of a guard with slightly fascist views who derives incredible joy and satisfaction from having the power to control and maintain order. As terrifying as it sounds, Kieślowski believed that this porter was not a bad man. He really thinks it would be good to publicly hang someone because then everyone would be scared and stop committing crimes. The final shot, enriched with Wojciech Kilar’s music, makes us feel not fear for this man, but simple compassion.

One more documentary, made a year later, Seven Women of Different Ages (you can watch it here) is a collection of shots depicting ballerinas of various ages (Witold Stok adds that they were all of his wife’s type), which, initially mistakenly interpreted only as a dance documentary, gives a poetic and extremely moving image of passing time.

When he finished these two documentaries (From the Point of View of a Night Porter and Seven Women of Different Ages), he told one of the journalists: For eight years, I haven’t had the feeling that I’ve finished anything. One stage ends and another immediately begins. I don’t have a moment of mental peace. A sense that the holidays are starting. Immediately after, he began working on Camera Buff (1979), where once again, he cast Jerzy Stuhr in the lead role. It is the story of a man who buys a camera to film his newborn daughter. However, over time, filming becomes his true passion, and his potential and skills are noticed by the director of the plant where Filip Mosz (Jerzy Stuhr) works. Unfortunately, the camera, which was supposed to document the child’s growth, becomes a source of conflicts, troubles, and tensions. Jerzy Stuhr, in his recollection of Kieślowski, writes: The film Camera Buff was supposed to end differently. When the protagonist learned that his actions had hurt another person, he decided to break off his promising film career. He opened the box of film stock and exposed the negative, throwing it away. Symbolically, he broke with art. (…) A few weeks later, Kieślowski called me. Listen, we need to reshoot the ending. Why? Because it’s not true. I’m lying! I won’t stop making films, I won’t throw away a meter of tape, I can’t deceive people like that! (…) A week later, we shot one of the most important and beautiful scenes in post-war Polish cinema. Slowly, I turned the camera on myself, pressed the switch, and began to recount my life again, how my child was born, and so on…

Many reviewers felt that the film reflected the personal struggles of the director and his drama – the drama of realization, which Kieślowski did not deny and which significantly influenced the authenticity of the story and characters. Kieślowski valued truth above all else.

The year 1980 was again a time for documentaries; during that period, he made the short films Station and the famous Talking Heads. Let’s start with Talking Heads, a film constructed in a very simple way: a group of people, of all ages (from a one-year-old baby to a hundred-year-old woman), were asked the following questions by the director: When were you born? Who are you? What do you want in life? Ultimately, Kieślowski selected forty-four people, creating a portrait of society with all its dreams and goals, weaknesses, and doubts, which also painted a picture of contemporary reality.

Station, on the other hand, marks the end of a certain stage for Kieślowski, ending his career as a documentarian (he would return to this genre only once more in 1988 with the short film Seven Days a Week, which was part of a series of films by various directors about different cities for the Dutch cycle City Life). The filming took place at night, using a semi-hidden camera to observe people’s behavior at the station: someone fell asleep, someone waited for a train, someone struggled with new luggage lockers – seemingly a safe topic, nothing invasive that could attract the authorities’ attention. However, one day, after another night of filming, the militia confiscated the filmed material. The director did not understand why, and no one wanted to explain it to him. After a few days, the tapes were returned to him, also without any comment. Some time later, it turned out that on that night, a girl had murdered her mother, chopped her into pieces, and put her into two suitcases. And then, at the Central Station, she placed them in one of those lockers. The militia was looking for evidence, but Kieślowski’s recordings were not such. But what did I (Kieślowski) realize then? That, unintentionally, completely independently of my intention and will, I could have become an informant (…) a collaborator with the militia. It was a moment when I understood that I didn’t want to make documentaries anymore (…)

So, we now move on to feature films, with the next in line and the longest in his oeuvre being Blind Chance (1981). The length of the film is likely due to its structure, as it contains three stories, all starting with the same event – the main character, Witek Długosz (played by Bogusław Linda), runs to catch a train. However, the outcomes differ: he catches the train; he runs into the railway guard; he misses the train. The director described it as a depiction of certain forces that influence human fate, pushing a person in one direction or another.

While still struggling with the editing of Blind Chance, his new TV film Short Working Day (1981) was already finished. The screenplay was based on a report by his friend, the well-known writer Hanna Krall, titled View from the Window on the First Floor. It was a fact-based story about a party secretary whose committee building was set on fire during a strike caused by price increases. The secretary managed to escape from the burning building at the last moment. A classic political film. However, Kieślowski was not satisfied with the final result, later explaining (but not excusing himself) that they didn’t make enough effort to delve into the character of the protagonist.

The next film by Kieślowski – No End (1984) – marked the beginning of his collaboration with three people who played a significant role in his work: co-writer (and lawyer) Krzysztof Piesiewicz, composer Zbigniew Preisner, and actress Grażyna Szapołowska. Initially, Kieślowski intended to make a film showing the workings of the court, but he did not know the legal environment. This issue was quickly resolved by Hanna Krall, who introduced her friend to Piesiewicz. This duo worked together until the end. The easing of court sentences in 1982 caused the director’s concept to change slightly, and ultimately a deeply emotional story was created. Urszula (played by the phenomenal Grażyna Szapołowska), the widow of a deceased lawyer, only realizes how much she loved her husband after his death and cannot find herself in her new reality. Kieślowski said that this film is like three films in one. First, there is the worker’s case that her husband was handling, second, the woman’s struggle with being a single mother and her new life, and finally, the metaphysical part where the deceased lawyer (Jerzy Radziwiłowicz) appears.

Agnieszka Holland recalls that this film was rejected by practically everyone: in martial law Poland, it did not fit the established political divisions, and abroad, few understood it. However, she was deeply moved by its exceptionally personal tone of despair. We met with Piesiewicz on the street. It was cold. It was raining. I lost one glove. Piesiewicz said: “We need to film the Decalogue, you should do it.”

The idea seemed crazy and abstract at first, and such was the initial impression on Kieślowski, but he knew it had to be done. They succeeded. Ten hour-long TV films were made, of which two – A Short Film About Killing (corresponding to the fifth commandment, Thou shalt not kill) and A Short Film About Love (corresponding to the sixth commandment, Thou shalt not commit adultery) – also had their theatrical versions.

The action of the Decalogue is set in a large residential complex, which was then considered one of the most beautiful in Warsaw. There, our characters live and occasionally meet, although rarely, because each episode is dedicated to a different character or pair of characters, which negates calling it a series. The Decalogue is an attempt to tell ten stories – fictional, narrative, which can always happen in any life (…). My characters are essentially engaged in what they always are. I focused more on what happens inside them, rather than what is outside.

Almost every one of the ten stories was made by a different cinematographer (only one – Sławomir Idziak – worked on two films). This way, the director wanted to achieve a diversity of styles, perspectives, and solutions. And despite giving the cinematographers a really free hand and each doing it their own way, a certain uniform poetics was maintained, which Kieślowski explained as something like the spirit of the script, which every good cinematographer correctly understands.

On the screen, we could also see a whole array of top actors, including Henryk Baranowski, Krystyna Janda, Daniel Olbrychski, Adrianna Biedrzyńska, Anna Polony, Ewa Błaszczyk, Piotr Machalica, Jerzy Stuhr (along with his son), Olaf Lubaszenko, Grażyna Szapołowska, Mirosław Baka, Krzysztof Globisz, and many others.

A Short Film About Killing (1988/1989) tells the story of a twenty-year-old boy (played by then-debutant Mirosław Baka) who, for reasons unknown, kills a taxi driver, but then the law kills him. The first of these scenes lasts about seven minutes, and the second about five. An American once said that it is the longest murder scene in the history of cinema. Kieślowski commented: This film is not really about the death penalty but about killing in general. Killing is evil, no matter why you kill, no matter who you kill, no matter who kills. The cinematographer, Sławomir Idziak, used greenish filters to amplify the cruelty of the depicted world. The heart stops, and saliva dries in the throat.

A Short Film About Love, on the other hand, is the story of a young postal worker, Tomek (played by Olaf Lubaszenko), who watches Magda (played by the extremely feminine Grażyna Szapołowska) through a telescope every day. However, his observation doesn’t end there; the boy confesses his love to the older woman, to which she does not react enthusiastically, even taking revenge by staging an erotic scene with another man. Tomek is devastated and attempts suicide. This intriguing story, while exploring voyeurism, also delves into themes of naivety, loneliness, the search for love, and human sensitivity.

After The Decalogue, some critics wondered what Kieślowski would come up with next to surpass the global success of these ten films. They joked it might be an eleventh commandment. Instead, he conceived The Double Life of Veronique. The title took a long time to decide upon, as it had to be defined early for Western productions (the film was produced in France). Initially called The Chorister, it didn’t resonate well in France, with someone saying, Oh God, another Catholic film from Poland. Finally, the title The Double Life of Veronique was chosen, which sounded good in other languages as well.

The editing process seemed endless, with nearly twenty versions of the film created. Kieślowski explained this problem by saying, You can’t show too much—the mystery disappears. You can’t show too little—no one understands anything.

Ultimately, a film emerged about sensitivity, intuitions, and difficult-to-name, irrational connections between people. On screen, we see two identical Veroniques (both played by the same French actress, Irène Jacob, who would also star in the later Red), unaware of each other’s existence, but when one (Weronika) dies, the other (Veronique) is enriched by her knowledge. The subtle film, without a fast-paced plot, captivates us almost unnoticed, especially thanks to Preisner’s poignant music, which particularly enchants the female audience, as the essence of the film is a woman.

Kieślowski’s filmography ends with the Three Colors Trilogy, referencing the slogans of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, and fraternity. The titles are Blue, White, and Red (the colors of the French flag). These are three separate films meant to be watched in that order, though the sequence can be slightly modified. We will, however, look at them in the order proposed by the author.

In Blue (liberty), we observe a woman (played by Juliette Binoche) who, after the death of her husband, a great composer, and her daughter, tries to forget what happened and start a new life, albeit with little success. She attempts to free herself from the past. Music, composed by Zbigniew Preisner, plays a significant role here, with musical notes frequently appearing on screen and the actual process of composing being shown. Kieślowski even said that, in a sense, this is a film about music.

White (equality) significantly differs in tone from the previous Blue, often described as a bitter comedy full of events and unexpected twists. It tells the story of Karol (played by Zbigniew Zamachowski), whose wife leaves him, making him feel humiliated. He decides to prove, especially to his wife, that he is better than others at any cost. This ironic work by Kieślowski is a testament that equality in the modern world does not exist.

Kieślowski’s last film, Red (fraternity), shows Valentine (again played by Irène Jacob), who accidentally hits a retired judge’s dog with her car. She tries to return the injured animal to its owner, but he refuses to take it back, which irritates and discourages her. However, fate brings the two protagonists together again, and a spiritual, brotherly bond slowly begins to form between them.

The unique atmosphere of Kieślowski’s films, his keen eye for the beauty and dramas of this world, his sensitivity towards people, and his pursuit of truth make him an exceptional creator. He has forever etched himself not only in the history of Polish cinema but also in the hearts and minds of every viewer, as the truths conveyed in his works remain relevant and deeply touching—reaching the very essence of what Kieślowski valued most: humanity.

Words by Dominika Grochowska