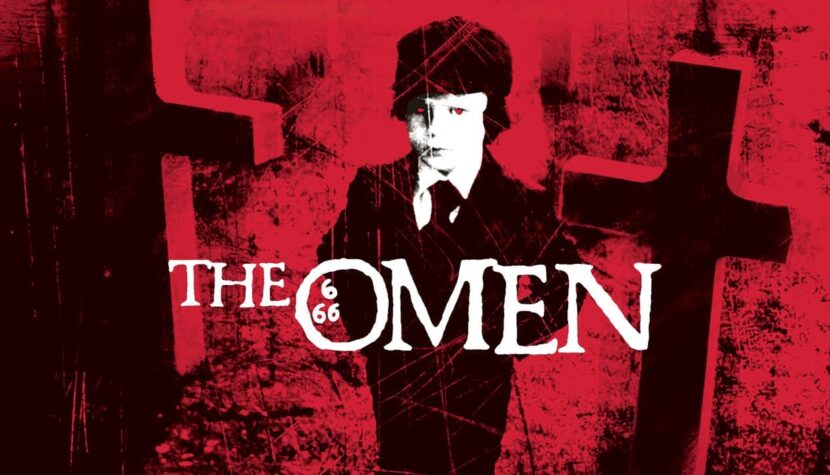

THE OMEN (1976). Genuine occult horror masterpiece

The image of the Eternal Adversary of humanity, portrayed as a nearly comic book-like character with horns and a tail, has become quite outdated since medieval times. Today, the human imagination is dominated by demons from the reality that surrounds us: wars, murders, civilization diseases, politics. In the era of hundreds of channels on television, the Internet, and virtual reality, it seems we are forgetting the foundations upon which our world is built. And yet, in most of us, there still lingers a deeply rooted awareness of the existence of the “other side,” undefined but somehow palpable, not through our senses but through intuition. This contradiction between life’s pragmatism and the fear of the unknown hidden within us is skillfully exploited by all sorts of contemporary charlatans: television evangelists, healers, cults, and… filmmakers.

The Omen, as a cinematic work, is precisely such a perfect form of charlatanism. It feeds on subconscious fears, uses references to widely known religious themes, and plays with archetypal anxieties. The Omen is a representative of the genre initiated by Rosemary’s Baby, emerging from the tradition of gothic novels, filled with dark forces and supernatural phenomena. However, what sets it apart from its gothic predecessors is not only its setting in familiar realities but above all its skillful manipulation of the viewer’s emotions. Superficially simple, it leaves disturbingly much room for interpretive acrobatics capable of eliciting a shiver of excitement in any horror enthusiast. The age-old division between good and evil is not so obvious in it after all.

At the sixth hour, on the sixth day, of the sixth month in Rome, a boy named Damien is born. On the same day, just after the birth, the son of the American ambassador to Italy, Robert Thorn (Gregory Peck), dies. Thorn, fearing for his wife (Lee Remick), who is unaware of the child’s death, agrees to an informal adoption of Damien, who will now be raised in luxury fit for an aristocrat. After several years, a series of accidents leads to a family tragedy, and as a result, Thorn turns against his adopted son. Everything points to Damien being the embodiment of the Antichrist. However, upon closer examination of the story, one might conclude that Robert Thorn’s mad crusade against his own child carries the marks of madness.

Richard Donner, the film’s director, importantly refrains from overusing clear symbolism and does not sensationalize unexplainable phenomena. This creates the impression that the events we witness may not necessarily be the result of supernatural forces. Could it be just the deepening psychosis of a diplomat burdened by responsibilities? Then who is truly evil in this story? The Omen caters to our imagination, our vision of the reborn Adversary—misleading us. We would like it to be that simple; we want to think that if the Antichrist were ever to “honor” us with his presence, he would take a familiar, physical form. Accustomed to perceiving the sensory, we assume that if something has a shape we know, something we encounter every day, we will handle it more easily. Human nature makes it seem attainable to overcome the Adversary. But in the end, as Leonard Wolf writes in the introduction to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, “…hell begins and ends in a person’s soul.” “Not in their body,” one might add.

David Seltzer, the screenwriter of The Omen, masterfully incorporates several highly evocative and suggestive quotes from the Book of Revelation by Saint John. These quotes resonate with the viewer’s imagination and lend an air of credibility to the spectacle. Seltzer also appears to have a slightly ironic sense of humor. He allows the presumed Antichrist to be born in Rome, the capital of the Catholic world, and lets him grow up in London, the capital of Anglicanism, symbolically separating him from papal influences. Finally, he plans to have him killed by the hands of his adoptive father, assisted by a monk named Bugenhagen, residing in the Holy Land. Even the choice of this name seems deliberate, as Johann Bugenhagen was a prominent figure in the 16th century and a close associate of Martin Luther, significantly contributing to the spread of the Reformation in Germany and Scandinavia. This entire subplot appears to be a significant religious allusion, although in the midst of the emotions stirred by watching the film, this subtle detail may escape the viewer’s attention.

Someone once said that the true role of the Adversary is to blur the fragile boundary between what’s black and white, evil and good, certain and uncertain. Their task is to make us lose our way, leaving us vulnerable as we navigate the thicket of meanings that we can’t fully grasp. The Omen, drawing on Christian mythology, playing on the viewer’s fears, and enhancing the experience with an excellent musical score (Jerry Goldsmith’s outstanding composition), introduces an element not often seen in contemporary cinema – genuine fear.