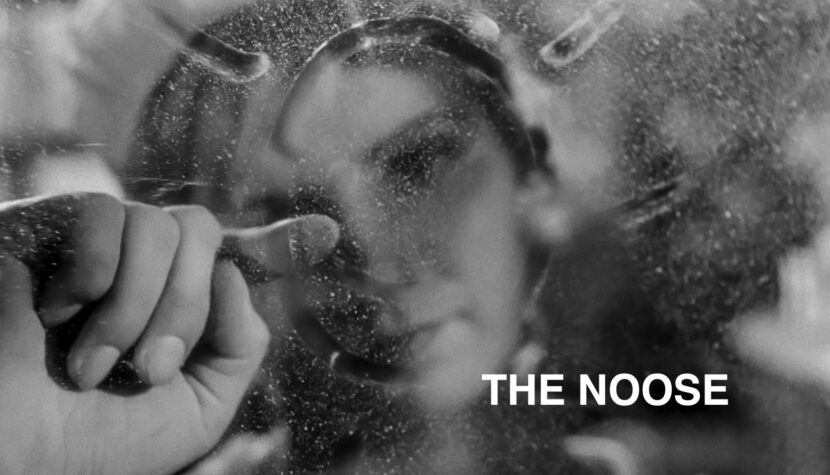

THE NOOSE. A study in weakness from the director of Saragossa Manuscript

Marek Hłasko knew this very well, as his unique style for the socialist realism era made him a master in portraying human dramas steeped in the drabness of the Communist Poland. One of the most poignant testimonies of that era is The Noose, which, despite being released almost seventy years ago, still amazes with its directorial perfection and timeless message.

It is no coincidence that Wojciech Jerzy Has (The Saragossa Manuscript, The Hourglass Sanatorium) earned the title of a leading visionary of Polish cinema. From the beginning of his career, the outstanding director showed that he wanted to extract as much emotion as possible from the stories shown on the big screen. After years of honing his craft through numerous short forms, it was finally time for his full-length directorial debut. Shot in 1957 and presented to the world on January 20, 1958, The Noose floored audiences then (and still does), yet today it seems to be one of Has’s less frequently mentioned works – which is odd, considering its literary basis was one of Marek Hłasko’s most popular stories.

The story of Kuba Kowalski (Gustaw Holoubek) – once a promising painter who literally drank his talent away – moves the audience even before the screening truly begins. During the opening credits, with the background of a telephone in the foreground and the silhouette of the protagonist in the background, the audience is accompanied by the unsettling compositions of Tadeusz Baird, performed by the Great Symphony Orchestra of Polish Radio in Katowice. The haunting music and the masterful camera work by Mieczysław Jahoda (Knights of the Teutonic Order, The Saragossa Manuscript) are undoubtedly the most significant features of Has’s debut, creating an incredible atmosphere for The Noose.

We meet the main character in the morning during a conversation with his beloved, Krystyna (Aleksandra Śląska). The atmosphere is tense, although initially, the dialogue unfolds in a way that masks their true topic from the viewer (assuming they haven’t read the story), as if the characters were speaking in a code known only to them – but this quickly becomes clear. Kuba is an alcoholic, and Krystyna is doing everything she can to pull her lover from the abyss. They plan to start a treatment and agree to meet the doctor at 6 PM. The woman leaves.

Sitting at home for seven hours seems trivial, but Kuba’s condition complicates everything. Everyone knows the feeling when a significant change is about to happen in life – time seems to stand still, everything feels simultaneously close and distant, and one feels like they are coming apart. To make matters worse, the phone in the protagonist’s apartment doesn’t stop ringing – friends have learned of his plans, everyone congratulates him, offering advice that only unsettles Kuba further. He feels increasing pressure, unable to stand the sight of the empty room brought to life only by the loud ringing phone. He can’t take it – despite his promise, he leaves the house.

The motifs of a peculiar journey and the carefully conducted countdown build tension perfectly. Each person Kuba meets checks the time or asks for it, intensifying his feeling of entrapment, from which he was trying to escape. This is already evident at home, from where he watched the clock on a nearby building through the window – each moment making him look like he was starting to choke, but leaving didn’t change anything. Each step took Kuba further from his goal, transporting him into a slightly different world. As if he were dreaming, and his actions were determined by an overarching force, leaving him no choice.

I dreamed that I was a drunk; that my name was Kowalski; that there was a telephone in my house – do you understand? – I dreamed that I wanted to forget about my drunkenness. Escape from the people I drank with, from the bars, from the memories. This happens sometimes in a dream, right? But in a dream, you can’t escape anything. And that’s the worst part.

This dreamlike quality is strongly perceptible here – but there is no blurring of the lines between reality and dream. In this case, all visions are drunken delusions, leading Kuba to his fate.

The Noose (both in Hłasko’s story and Has’s film) is a deeply emotional and moving portrayal of a person trapped in addiction, whose life – despite the semblance of struggle – has long been written off. The neighbors, friends, and even those who knew him only by sight had become accustomed to the protagonist’s drunken exploits. So had he. Kuba knew that the label was not given without reason – he called himself a drunk while pretending not to care about others’ opinions. This cynical attitude adds bitterness to Has’s film, a bitterness felt in most of Hłasko’s stories – something seemingly normal in the Polish reality of the 1950s. The protagonist only in rare moments of euphoria seemed to genuinely hope for a change in fate. Unsurprisingly, these moments occurred precisely after consuming alcohol.

We, who drink, know it doesn’t matter why. Maybe I’m lonely, maybe a whore who I can’t breathe without betrayed me. It doesn’t matter. There is no misfortune, loneliness, woman worth drinking for, but only those who have drunk away everything – those who have to drink – know this. Vodka is the truth, understood always too late.

The film adaptation of The Noose is perhaps slightly milder than its literary counterpart – some threads were cut, some slightly enhanced, but Has and Hłasko, who worked together on the screenplay, did a solid job, further deepened by Mieczysław Jahoda’s unconventional camera work. Hłasko, who had his own demons, always liked to infuse his works with inadvertent moral messages. He didn’t judge anyone, didn’t divide people into good and bad, only highlighting the drab socialist reality through their examples, but casually, somewhere between the lines, he pointed out the right path – one he often didn’t take himself.

Ultimately, The Noose is a very bitter and hopeless display of human impotence in confronting the most dangerous opponent – oneself. The lack of prospects and the pervasive sense of hopelessness that particularly plagued Poles in the 1950s are visible in literally every character in the film. But only the drunks and the women who believe in their redemption are timeless.

Words by Damian Halik