The Long Kiss Goodnight Explained: The Real Captain Marvel

…, and yet Marvel is supposed to mean wonder, marvels beyond belief, awe. Meanwhile, there is nothing here to be in awe of. The action takes place in the 1990s, but even if this film had been made back then, it wouldn’t have surprised audiences with anything new, especially plot-wise. A young woman with amnesia (played by an Oscar winner), trying to uncover the truth about her past, discovers that she has a true killer inside her, a war machine, an indestructible warrior. In the meantime, she finds support in a character played by Samuel L. Jackson, although he seems to slow her down rather than truly help. One such film was already made years ago, and especially after watching Captain Marvel, it’s worth refreshing that film, just to see how action cinema should look. Renny Harlin knew this when he made The Long Kiss Goodnight in 1996.

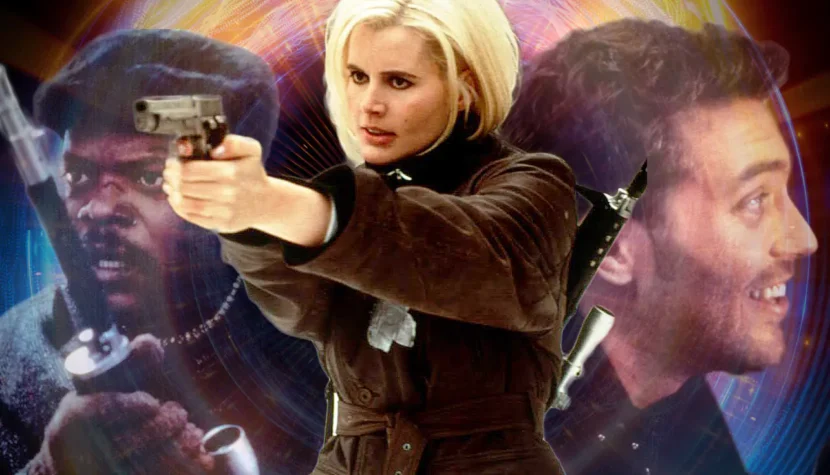

Plot-wise, there isn’t much more than I’ve already written, though the devil is in the details. After eight years of peaceful life as a model housewife, teacher, and mother, Samantha Caine (Geena Davis, first with long dark hair, then with short blonde hair and heavy makeup) becomes the target of assassins who clearly know more about her than she does. Mitch Henessey (the aforementioned Jackson), a third-rate private detective hired by the woman to learn who she was before the sea spat her out years ago with a gunshot wound to her head and in her second month of pregnancy, knows even less. He is surprised and genuinely amused when it turns out that Samantha was once called Charly Baltimore and worked as a government operative. Worse for both of them, her employers and enemies would prefer her dead than alive. Soon, Caine/Baltimore and Henessey become a difficult target to kill for an entire army of assassins, the worst of whom seems to be the charming and cruel Timothy (captivating on screen but ultimately underused Craig Bierko).

This is neither the best nor the most original script written by Shane Black, author of Lethal Weapon and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. It is definitely the most expensive one – for his script, Black received a record fee of four million dollars, though, just like with his earlier scripts for The Last Boy Scout and Last Action Hero, the version we see on screen is a cut and softened version of his original story. That doesn’t mean Harlin’s film shies away from brutality, but it’s drowned out by numerous explosions, shootouts, breakneck-paced action, and a healthy dose of humor that manifests in typical Black dialogues. When asked whether he’s always been stupid or took lessons, Jackson’s character replies that, of course, he took lessons; another time, Samantha explains that she can’t be a secret agent since she’s part of the parent-teacher committee, though the final word will belong to her CIA superior (That’s a write-off!). The latter is played by Brian Cox, delivering the funniest lines with a stone face and the attitude of a man who’s no longer surprised by anything. Perhaps except for the duck drawing, though probably anyone in his place would have doubts about what Henessey had drawn in his notebook.

The Long Kiss Goodnight – a title that beautifully reflects Black’s admiration for noir thrillers (in one scene, the characters even watch The Long Goodbye by Altman on TV), but not necessarily the dynamism of action cinema, which Harlin’s film undoubtedly is. The creator of Die Hard 2 and Cliffhanger shoots his third high-octane masterpiece of the 1990s, perhaps more than before allowing himself to deviate from realism for the sake of the most explosive final effect. When Davis flies out through the front window of a car after colliding with a deer, not only does she not break her neck, but she quickly gets up to relieve the injured animal. In another scene, Jackson is launched into the air, crashes through a billboard, and lands in the snow, where, almost instinctively, he reaches for a knife and kills an approaching enemy. Harlin knows how to film even the most implausible action scenes so that not only do they not provoke our resistance, but they amaze us, making us beg for more. And we get more, especially in the finale, which copies just one year earlier’s Die Hard with a Vengeance (again, we get the scenery of the American-Canadian border and a helicopter chase with a villain with a rifle on board), but it does so in such a bombastic and overloaded way that we easily forgive the imitation.

Harlin’s directorial mastery pours out of the screen when we watch the further exploits of his then-wife in a repertoire that was mostly reserved for men back then. Davis had already been seasoned by their earlier film, Cutthroat Island, though both probably would prefer to forget about the flop of that adventure spectacle that sank the Carolco studio. The Long Kiss Goodnight was supposed to be made even before Davis and Harlin started shooting their pirate production, but contracts were already signed, and the money was ready, so they had no choice. Who knows, if it hadn’t been for the failure of that film, their female version of Jason Bourne’s adventures might have been a hit. However, audiences were already prejudiced against the duo, resulting in another flop, despite decent reviews.

Personally, I believe Davis looks amazing as a heroine in action cinema, though her role forces the entire film into a convention that is sometimes hard to swallow. On one hand, we have the tender, loving, gentle, and kind Samantha, and on the other, the cold-as-ice, ruthless, and willing to sever all ties with her family, Charly. Two opposing poles, characters so radically different that they must clash. Harlin initially presents this dichotomy in the form of a nightmare, where in her mirror reflection, the exemplary mother sees her dark alter ego; it has the flavor of b-movie horrors that the Finnish director made early in his career (Prison, A Nightmare on Elm Street 4). But every time one of the heroine’s personalities reacts in a way reserved for the other, the contrast is so strong that even Davis cannot overcome the absurdity or excessive melodrama of the situation. The first we see when Samantha chops vegetables with the skill of a chef (or professional killer), though Harlin brilliantly punctuates this moment; the second we see when Charly cries for her daughter, allowing herself to show deeply hidden emotions. In both cases, these scenes are, at best, unconvincing, and at worst, more implausible than the action sequences.

The Long Kiss Goodnight is, if not the best, then certainly the most interesting when it focuses on the relationship between the two main characters, underscored at one point by quite a surprising sexual tension. The moment when Charly decides to use Mitch just because he’s available and she, as she says, hasn’t been on a date in eight years, surprises and introduces another change in their relationship dynamics. But not only there, which will be explained by a small digression. Contemporary action cinema was mostly devoid of full-fledged male-female duos, let alone ones where the woman would be the dominant partner. Most of the time, the partners were men – to name only 48 Hours, Lethal Weapon, or Bad Boys – which automatically ruled out any ambiguous relationship; just remember Marcus Burnett’s panic in the latter film when he hears that he and his police partner might be considered lovers.

However, there were mixed duos, though the woman’s role always boiled down to assisting her partner or getting into trouble, from which the main character was supposed to rescue her (Liberator, Demolition Man, Speed). An exception was Fair Game, where debuting Cindy Crawford was partnered with William Baldwin, and even in the plot, her character played a bigger role than his, even though he did most of the dirty work. Perhaps that’s why the film turned out to be a big flop, although the overall production level, flawless in execution, but script-wise relying on the most worn-out clichés in nearly every scene, may have also contributed. It’s no wonder that watching Geena Davis shoot, drive (and skate), and kill better than Samuel L. Jackson in an action film, where it’s usually the other way around, is rather peculiar, and as if that weren’t enough, Charly encourages him to have sex, even though a young daughter and a fiancé are waiting for her at home. These weren’t the kind of heroes we had in action cinema on a daily basis.

Additionally, Henessey’s reaction adds another element to this unusual picture when he describes the erotic situation between him and Charly with the words The beautiful white lady seduces the black servant. Black’s script not only notes Mitch’s skin color, who parades in the clothes of a retired white agent (tweed pants, yellow turtleneck, green club jacket, and beret) throughout most of the film, which only highlights his cheapness – and the fact that he is black! – but in one scene, it also introduces a thought-provoking connotation. Naked, beaten, bound, and frightened, the detective lies in the basement, waiting for death, and I feel that in today’s age of political correctness, an image that clearly evokes slavery would never be allowed in mainstream cinema. Does this in any way diminish Jackson’s character, making him weaker than he was before? No. Does it change our perception of his character? No. However, this image completes the picture of himself that Henessey has in his mind – a defeated, humiliated, and punished individual (we learn that he was previously a policeman who committed theft and went to prison), deliberately pushing himself to the margins, just so he wouldn’t get anyone’s attention.

It is not by chance that only he comments on his skin color, whether it’s the aforementioned issue during his seduction by Charly or when he calls her “Miss Daisy”, identifying with the black driver from the Oscar-winning film. Does this also explain his own failure? Black and Harlin do not delve that deeply, preferring to present him as a lost cause in the style of Joe Hallenbeck from The Last Boy Scout, ready for the greatest sacrifice if the stakes are worth it. I am not surprised that Jackson himself considers Henessey his favorite character he has played throughout his entire career. Audiences also loved his character and, in a way, saved him – in the original ending, Mitch dies, but after poorly received test screenings, reshoots were ordered, which gave us his completely different ending.

For Geena Davis, this was the last time she appeared in a leading role in a major cinematic film, unless we consider the two Stuart Little movies. For Shane Black, it was the last script before a nearly decade-long hiatus, after which he triumphantly returned, no longer just as a writer but also as a director. Renny Harlin made the popular Deep Blue Sea in the 1990s, then descended to second-tier productions, making cheaper and worse films before moving to China, where, somewhat surprisingly, he is building a career. Samuel L. Jackson, on the other hand, has been working as diligently as he did back then and continues to do so now, recently returning to his favorite roles. Not so long ago, we saw him in Glass, where he played the title character, familiar to anyone who has seen Unbreakable, and Captain Marvel as Nick Fury. And it is really hard for me not to see in the comic book spectacle a copy of The Long Kiss Goodnight…, even if only on a very basic level. The thing is, while the current film seems to do nothing new, Harlin’s action film gem has lost none of its energy and subversiveness in its role reversal. And Major Baltimore, as we learn in the film, is necessarily of a higher rank than some captain.