THE LION OF FLANDERS: A Film Both Worth and Not Worth Recommending

When it comes to broadening your horizons, it’s sometimes worth indulging in unconventional cinema. Take, for example, a Dutch “superproduction” (at least in theory) from the 1980s, which attempts to portray a pivotal event in the country’s history. The Lion of Flanders was meant to be a Flemish answer to Hollywood’s grand medieval spectacles, and European filmmakers sought to prove that they, too, could deliver. And prove it they did… by showing how not to make such films.

The script was based on a novel by Hendrik Conscience, one of Belgium’s most famous Dutch-language authors. His work centers on transformative events of the 14th century that led to the Battle of Courtrai, a clash between French knights and Flemish insurgents made up mostly of weavers, peasants, dyers, and butchers. Like Poland’s Henryk Sienkiewicz, Conscience wrote “to uplift hearts,” selecting significant historical events and characters and imbuing them with near-mythical significance. Coupled with a hefty budget, this project seemed like the makings of something akin to Braveheart or, bringing Sienkiewicz back into the picture, perhaps even The Deluge, right?

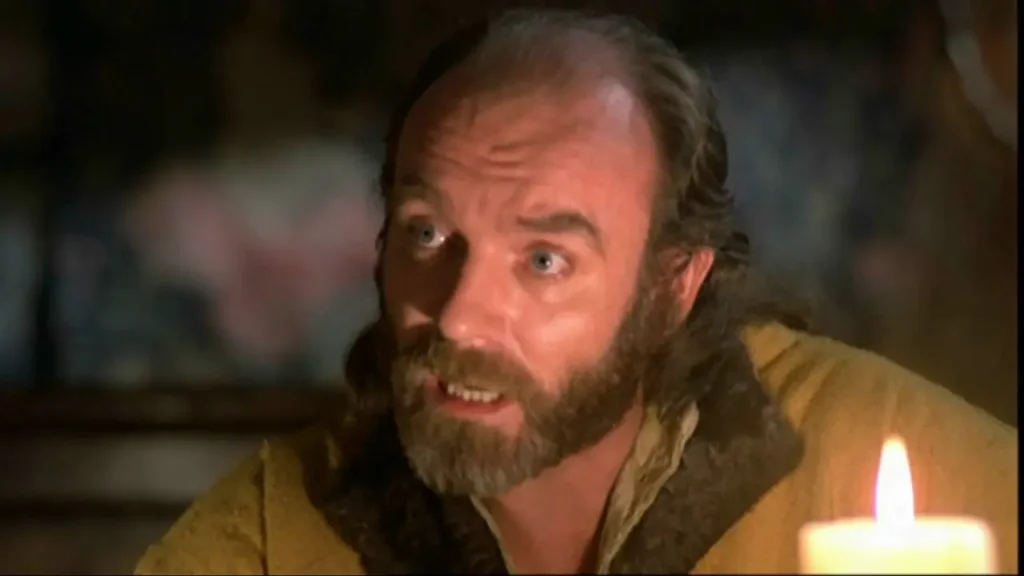

Not so fast. In reality, it’s hard to find a film so clumsily executed. Virtually every aspect falls short. Starting with the screenplay, penned by Hugo Claus, another celebrated Dutch-language figure—author, poet, director, and painter. It’s hard to even discern who the main character of this masterpiece is. At first, in a laughable scene where a prisoner is freed (a man runs into a circle of armed knights on horseback, unties the captive, and escapes into the forest without anyone stopping him), we meet the guild leader of the weavers (Jan Decleir). It seems his story will be central. But then he vanishes for a good half hour, and the camera shifts to Robrecht van Bethune (Frank Aendenboom). However, Robrecht also fades into the background at some point, leaving viewers wondering about his fate, as the guild leader reclaims the baton in this relay of embarrassment.

The film is rife with blunders: swords bend during fights, visibly made of rubber or some other material, and corpses can be seen moving their eyes to follow the living. Overacting is common, such as in an overly dramatic rape-and-murder scene that resembles a theatrical skit staged at a housing co-op. The pièce de résistance is King Philip IV of France (Peter te Nuyl), depicted as a man utterly devoid of intelligence or expression. The narrator even informs us that… the king never blinks (though this isn’t true, despite the actor’s best efforts). Making the cruel monarch a complete idiot might have been intentional, given that the French are portrayed as degenerate brutes in the film.

Set in the Middle Ages, the movie naturally features bloody skirmishes. One particular battle encapsulates the ineptitude of this (overly) ambitious project. Before a castle siege, the leader announces that the attack will take place at night. But they attack during the day. Moreover, there seems to have been an editing issue because the Flemish fighters first storm the fortress, finding it littered with dead defenders, and celebrate a grand victory, only for the castle assault to then start all over again in subsequent scenes.

The film’s climax was supposed to be the grand Battle of Courtrai, but it’s essentially non-existent. What we get is a few dozen costumed extras (one of whom has metal fish on his helmet) running back and forth, shouting and pretending to fight. Then, onto the battlefield strides… the Golden Knight. He stabs two Frenchmen with a rubber sword, and… that’s it, the Flemish win.

The Lion of Flanders is a curious case of a film that I both recommend and don’t recommend. It manages to do almost everything wrong, yet its clumsiness and ineptitude are oddly endearing. It’s worth experiencing firsthand to see how an epic historical tapestry can end up looking like a drawing made by a small child holding crayons the wrong way.