THE DUELLISTS. Ridley Scott’s first feature film is one of his finest works

When discussing the beginnings of Ridley Scott‘s career, Alien and Blade Runner are often mentioned first, while the earlier The Duellists is rarely brought up. This 1977 adaptation of a Joseph Conrad story won the award for Best Debut at Cannes, and the Italian Film Academy awarded Scott for Best Direction of a Foreign Film. Today, it seems like a forgotten work, uncharacteristic of the early stage of his career and often omitted from rankings of the greatest achievements of the director of Gladiator. This is completely undeserved, as this story of honor, which turns two officers of Napoleon Bonaparte’s army into mortal enemies, is a work of great beauty and surprising depth. It is also one of Scott’s best films.

The story begins in 1800 in Strasbourg. Colonel Feraud seriously injures the mayor’s nephew during a duel and is ordered to be placed under military arrest. Another officer, d’Hubert, is tasked with bringing him in, but their meeting takes an unexpected turn when Feraud, feeling insulted, challenges the messenger to a duel. Reluctantly, d’Hubert agrees and wins, though he is not entirely sure how he ended up on the other side of his rival’s blade. Over the years, they meet again and fight another duel. And then another. It soon becomes clear that this madness will only end with the death of one of them.

Conrad’s story, which has the tone of an anecdote (drawn, in fact, from a newspaper article about a series of real duels between two officers spanning many years), documents a conflict that is incomprehensible even to the protagonists’ acquaintances, fueled by a warped sense of honor. Feraud, in particular, seems to be a maniacal character, using duels as a way to assert his views and superiority. In reality, the opposite is true—every situation, every insult (real or imagined) serves as a pretext for him to grab a weapon and fight anyone who crosses his path. For Feraud, the truth matters less than the opportunity to engage in combat.

The story unfolds from the perspective of his rival, d’Hubert, a reasonable man who does not let his emotions take over but becomes increasingly ensnared by his rival’s unhealthy ambitions with each duel. D’Hubert does not want to fight but is forced to—this is demanded by etiquette, even if superiors view the duels with disgust, while lower-ranking soldiers, unaware of the backstory, look on with admiration. So, is it possible not to duel? It turns out that it is. A medic, friendly with d’Hubert, points out three conditions that can avoid an unwanted fight: the adversaries cannot be stationed in the same place; the duel can only take place if both are of the same rank; and wartime prohibits such engagements. “The duels of nations take precedence. Trust Bonaparte,” the friend says. Indeed, when Feraud and d’Hubert meet in 1812 in Russia, where the French army is decimated by the frost, fighting is out of the question.

Scott, however, presents a fourth reason for at least a temporary truce. When Feraud’s second is about to approach d’Hubert with an invitation to another duel, an unexpected intervention by a woman in love with him saves the day. She only delays the inevitable, but the subsequent arc involving Laura—who was absent in Conrad’s literary original—is significant. She is not only a potential salvation for d’Hubert but also the only character who openly opposes Feraud’s twisted need for combat, which he claims to be honorable. It is no surprise that the duel that follows Laura’s departure is the bloodiest and longest of them all, devoid of resolution and stripped of the elegance characterizing previous bouts. Feraud is exposed, d’Hubert loses his love; they throw themselves at each other like wild animals, ready to fight to the death.

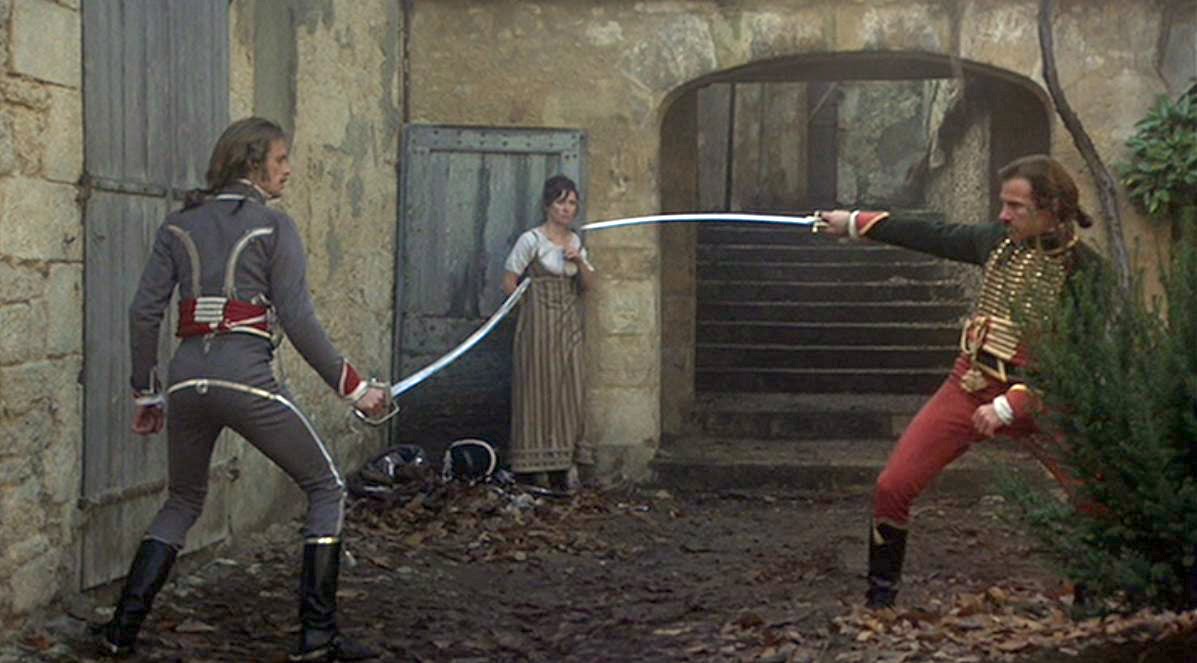

The story does not end there. Making his cinematic debut, Scott—until then a renowned commercial director—pays equal attention to the psychological depth of the story and its visual execution. This is a visually stunning film, with painterly frames reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (an obvious inspiration for Scott), and the hand-held camera work during the duels surprises with its dynamism and raw realism. What stands out most are the sounds of the weapons wielded by the duelists—loud, sharp, emphasizing the emotions of the fight while expressing the frenzy of the attacking side.

No duel resembles the previous one; each has a unique rhythm, style, length, and staging. They largely reflect the psychological state of the protagonists, perhaps more so d’Hubert than Feraud, as the latter’s attitude toward his rival remains unchanged. In Harvey Keitel’s portrayal, Feraud is a man driven by obsession, restless, and interpreting his hatred for d’Hubert in his own way. Meanwhile, Keith Carradine’s d’Hubert, with his stoic demeanor, appears to avoid awkward situations that might tarnish his reputation. Surprisingly, he expresses himself most fully in combat. Thus, the action complements the psychological portraits of the characters—for one, it is an end in itself; for the other, an unconscious need for expression.

Much is said about honor in The Duellists and much about Napoleon. Scott’s debut can be seen as a metaphor for Bonaparte’s downfall (especially since, as the story progresses, Keitel’s character increasingly resembles the French emperor) or as a study of contagious madness. However, more important than d’Hubert’s moment of submission to his rival’s warped mindset is the moment he achieves true happiness by freeing himself from the necessity of continuing their private war. The final duel, though not lacking in tension, has a calm rhythm and a conclusion that confirms the ultimate victory of one over the other. Yet the duel is entirely unnecessary—even before it begins, it is clear who the winner and the loser are.