SUSPIRIA (1977). Dario Argento’s horror masterpiece

There are more subtle horrors, aimed at evoking unease in the viewers, a strange state of mind that lingers long after the screening. Or those that do not belong to this genre but still terrify us to the core.

Even before Suspiria truly begins, director Dario Argento assaults the viewer’s senses. The loud drums and strings accompanying the opening credits quickly give way to a music box melody that transforms into something more predatory and ominous. Here and there, the voice of the Goblin band’s vocalist breaks through, uttering only one word – “witch.” There’s also a narrator recounting the arrival of a young American, Suzy Bannion, in Freiburg to study at the famous ballet school.

Indeed, the first image we are presented with in Suspiria is that of a young woman, leaving the airport at night, looking friendly and normal. However, this opening scene is already unsettling. The camera films the protagonist as she walks towards the exit, capturing airport sounds in the background. But when it changes its perspective, observing her journey through her eyes, the innocent children’s tune from the opening credits returns. A cut to Suzy, and the melody disappears, replaced by the sounds of the arrivals hall. Another change of perspective, and once again, we are accompanied by the suspiciously innocent composition. Does the girl hear it as well? It’s as if the heroine has been warned right from the start about the dangers awaiting her at the strange school.

In his 1977 film, Dario Argento ventured into the realm of fantasy for the first time, blending elements of horror, fairy tales, and even the Italian genre of thriller known as giallo, for which he was renowned. His peculiarly titled debut, the so-called Animal Trilogy, consisting of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), The Cat o’ Nine Tails, and Four Flies on Grey Velvet (both from 1971), combined detective films with scenes of quite brutal violence (especially against women) and a perverted playfulness stemming from narrative surprises. More important than the content is the way in which the director creates tension-filled sequences, with significant assistance from Ennio Morricone’s music and Argento’s technical expertise, often masking script inconsistencies. He managed to largely avoid these inconsistencies in Deep Red (1975), his best giallo film, in which he had already perfected his directorial craftsmanship. Therefore, it’s not surprising that after this film, he decided to take a break from his favorite genre and make something different.

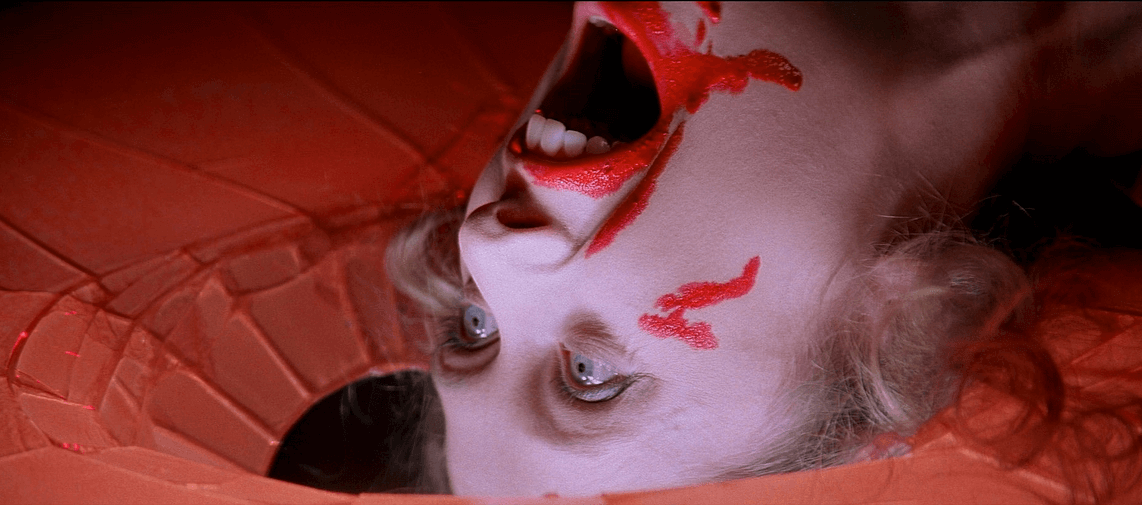

Argento co-wrote the script for Suspiria with his then-partner, actress Daria Nicolodi, drawing inspiration from her grandmother’s story about a school where black magic was practiced, as well as from the work of the 19th-century essayist Thomas De Quincey, Suspiria de Profundis. However, this time the story serves as a pretext for the director to create scenes designed not only to frighten or shock the audience but also to construct an entirely unreal world, a vision straight out of a feverish nightmare. The faces of the characters bathed in red light, the baroque decor of the interiors, and the glaringly vibrant wall colors in the school all strike the viewer with their artificiality, and the fact that Suzy finds it all entirely normal. We don’t hear words of admiration or any signs of surprise coming from her. She appears to have accepted it all without saying a word. And this silent acceptance might be surprising, but it shouldn’t be.

One of the characters of Suspiria attempts to leap over a room filled with barbed wire, even though she initially doesn’t see it, much like the audience. However, when she falls into it, it’s evident that she couldn’t have missed it. Some may consider this a logical inconsistency, but for the director, what matters most is the surprise caused by the sudden predicament the girl finds herself in.

The riddle that arises during the film is solved through counting steps, a method that seems sensible in its own way, yet somewhat detached from reality, evoking fairytale-like approaches. It’s reminiscent of breadcrumbs leading to an exit. Even the one moment that deviates from the rest, as it explains the origin of evil, stirs a subtle unease – cinematographer Luciano Tovoli at one point focuses not on the speaking characters but on their blurry reflections on the glass of a building. Meanwhile, a shot from below of the head of the demonology professor against the backdrop of a blue sky fills the viewer with a sense of hidden meaning in that scene. Compositionally and in terms of color, it is closer to the next film that Argento and Tovoli will work on together, which is Tenebrae (1982); here, however, it seems too distinctive to be meaningless.

The same applies to the characters, often measuring each other with their behavior or appearance – the students taunt and stick their tongues out at each other like little girls (the script was actually written with much younger actresses in mind). The stern and exceptionally composed Miss Tanner appears as a disciplinarian restraining her emotions, and Madame Blanc’s nephew, who helps run the school, is dressed in an outfit that is entirely out of place for the era. He is mainly in the company of the elderly cook, forming a strange duo with her. Add to this the English dubbing (most of the actors are Italians), which often strikes with exaggerated accents on certain words. The viewer identifies with Suzy not only because she is the nominal protagonist but also due to her ordinariness and the fact that the American actress Jessica Harper, who plays her, speaks in her own voice.

However, there are more things in Suspiria that can be off-putting.

The music in many scenes is decidedly too loud, the blood is excessively vibrant, and making sense of both specific episodes and the overall narrative is quite challenging. In other words, there will be those whom Argento’s film won’t scare but rather overwhelm with the abundance of ideas and the shock effect it aims to produce. But this is precisely what the Italian director intends. He wants to torment the viewer with a feast of colors and sounds, gore effects, and unexpected outbursts of violence. At the same time, he aims to enchant with images, even those that make one’s skin crawl. We are meant to feel not only like Suzy, helpless and trapped, but also like an invisible madman whose identity remains a mystery. In the creator of Deep Red, the killer’s point of view often becomes as important as, or perhaps even more important than, the victim’s.

The iconic fantasy horror film by Dario Argento gave rise to the development of its themes in the form of two sequels, together forming the so-called Three Mothers Trilogy. While Inferno (1980) is a successful film, albeit stylistically different from the original, the one created 30 years later, Mother of Tears (2007), serves as a sad testament to the director’s creative impotence.

Argento’s work will continue to impact viewers with its frenetic energy, visual aesthetics, and uniqueness. It’s challenging to find another film that even partially resembles the style and atmosphere of Suspiria.