SINISTER. The horror of facing the unknown

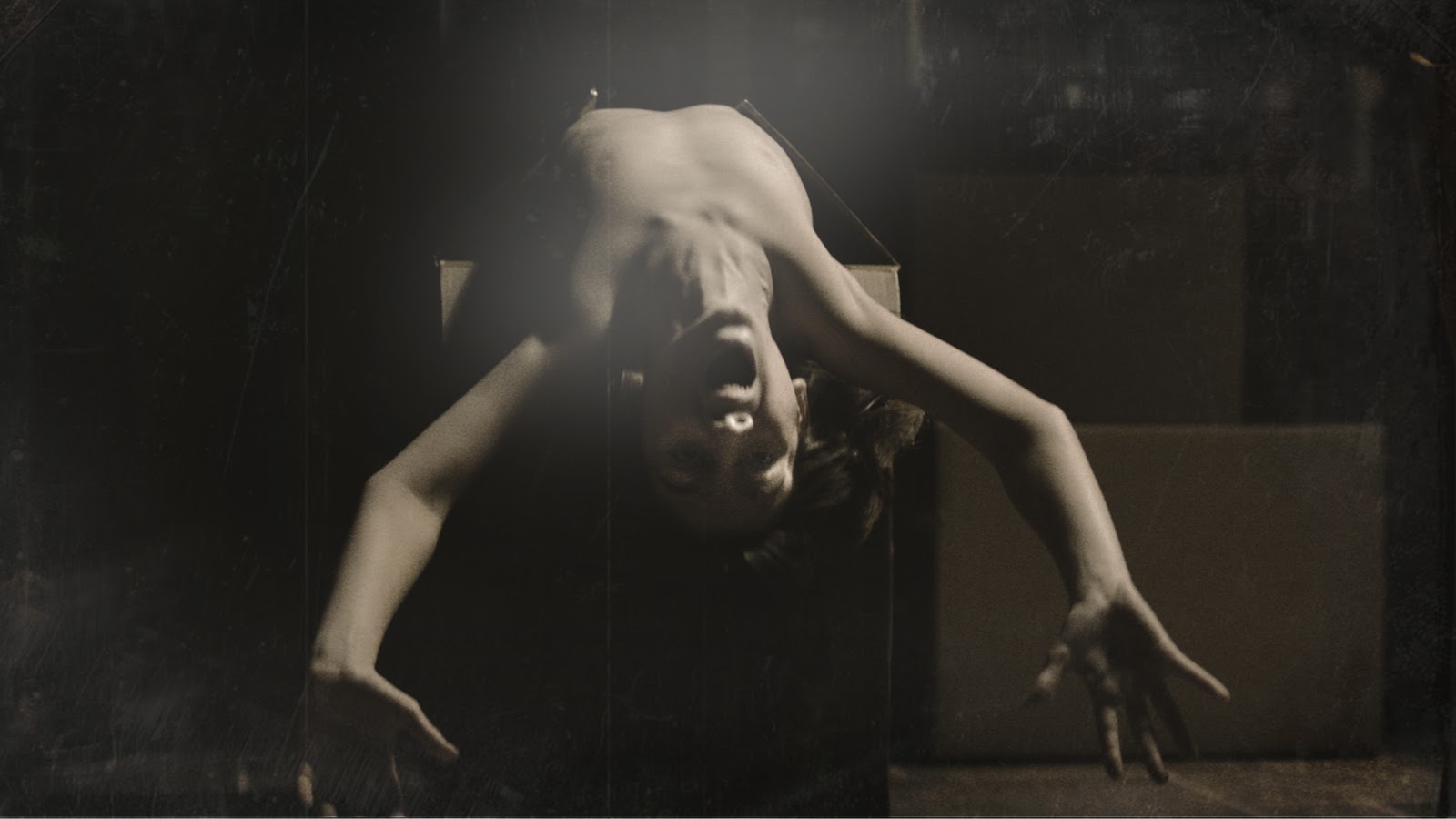

… – four individuals (later revealed to be parents and two children) stand hooded with ropes tied around their necks, attached to a tree branch. Suddenly, someone activates an electric saw, which cuts off the adjacent branch, lifting the hooded individuals, one by one, by counterweight. Their deaths seem inhumane, not just because of the method used. Firstly, we don’t see the murderer; the saw seems to move autonomously. Secondly, the entire scene is shot in one long and static shot with a Super 8 camera, perfectly suited for simple, family films. The question is, who is the author of this macabre recording.

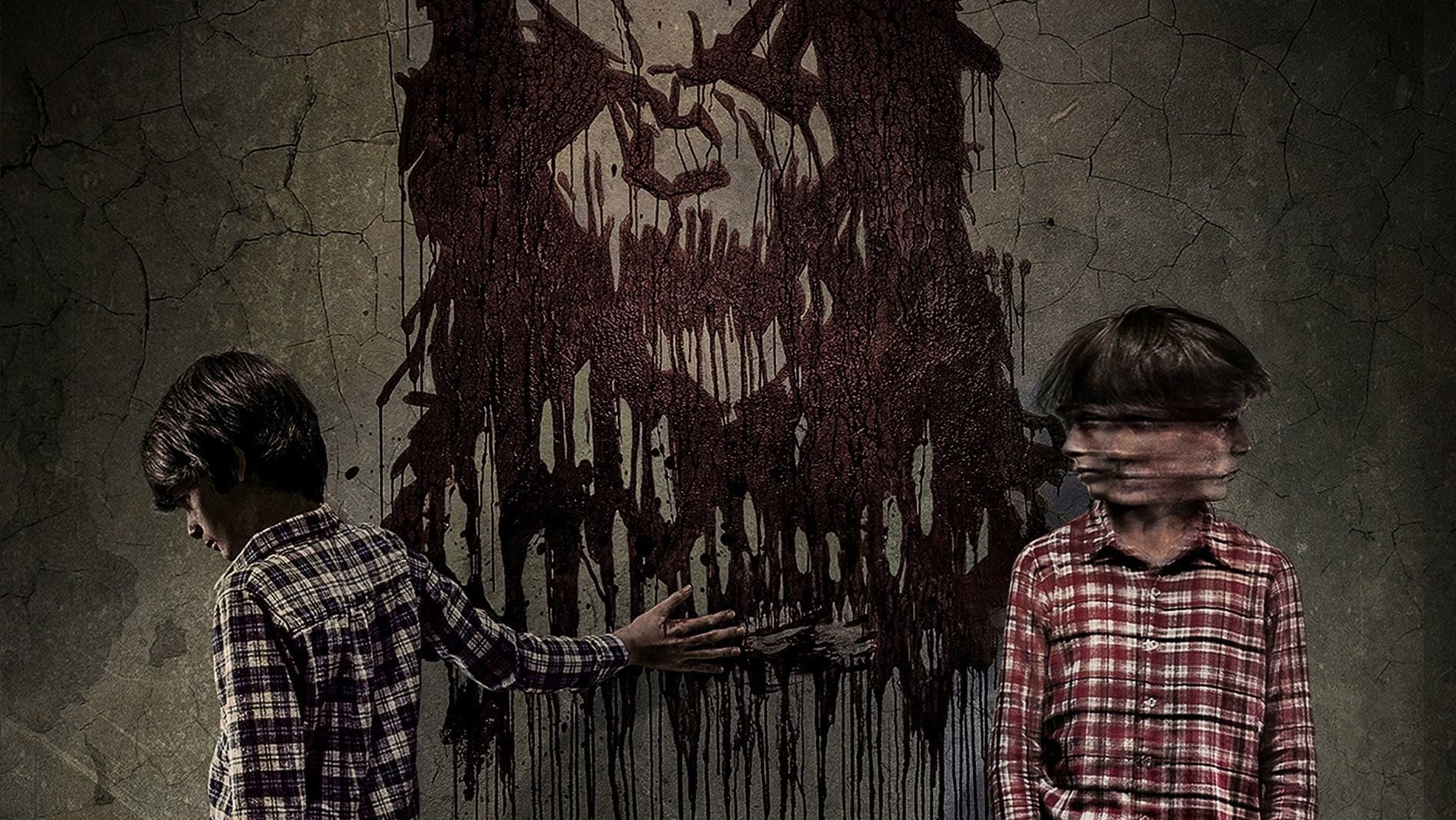

Several months later, a writer named Ellison Oswald moves into the home where the murdered family previously lived, with his wife and two children. On the first day, the local sheriff advises them to leave the infamous property immediately. However, Ellison, specializing in books about real crimes, knows that the history of the previous owners could give him the desired hit akin to his debut Blood in Kentucky. Yet, he hesitates to inform his family why he chose this particular house. In the attic, Oswald finds a box full of tapes and a projector that shouldn’t be there. At night, while everyone sleeps, he begins to watch the films, discovering with horror that they contain recordings of family murders dating back to 1966. Soon, he notices a mysterious figure present in each recording. Sinister it is.

Scott Derrickson‘s Sinister heavily borrows from classic horror cinema. The house the Oswalds inhabit can be considered haunted (closest to The Shining, also featuring a writer in the lead role), but the real horrors are born from the film reels, reminiscent of The Ring. Similar narrative solutions can be found here as in last year’s Insidious by James Wan, who himself drew inspiration from other famous horrors, especially Poltergeist by Hooper. The currently fashionable trend of found footage also plays a significant role, serving as the driving force of the film in Derrickson’s hands. Despite all this borrowing, Sinister stands out in its genre – it’s been a while since I’ve seen a horror film that didn’t try to cater to the audience. Although it has the qualities of mainstream cinema, it’s difficult to call it entertainment.

The mysterious noises in the attic, the unsettling music, or the ghost jumping out from behind the frame can scare multiple times, but alongside conventional methods of inducing fear, Derrickson successfully builds a sinister atmosphere that affects both viewers and characters. Trapped in the house like a rat, Ellison (played reliably by Ethan Hawke) watches recordings of cruel murders every night, trying to find a common denominator. He wants to write a great book, but for the moment, he becomes a slave to someone else’s creativity. The pattern of the films found in the attic is the same – at first, we observe a joyful family scene, followed by their violent deaths. This is illustrated with eerie music, which will surely find its fans. From one act of violence to another, passing through long nights, interrupted by short scenes during the day, during which Ellison often argues with his wife (very well-played by Juliet Rylance). Derrickson rarely allows moments of humor, mostly reserved for the deputy sheriff, who dreams of being mentioned in Oswald’s next book, in the acknowledgments.

In the dense and unpleasant atmosphere, it’s hard to find a clear point. And I’m not just talking about some irrational habit of Hawke’s character not to turn on the lights in a dark room. Even in the daytime scenes, the sunlight coming through the windows is pale, only enhancing the feeling of helplessness in the writer. After all, all he does is watch gruesome films, trying to figure out who their author is. Is Derrickson, along with his co-writer, C. Robert Cargill, criticizing film critics who persistently try to find something that isn’t there in horror films? Sometimes the best thing such a critic can do is not to delve too deeply into the film and base their rating solely on how many times they jumped in their seat during the screening. Otherwise, this work can lead to madness, or even death.

If I were to assess Sinister based on the amount of adrenaline jumps, it would receive a fairly high score, but Derrickson might feel offended by such a method. He’s more interested in evoking a sense of dread than fear – from the beginning, the viewer senses that the film’s protagonist is facing something he cannot understand or overcome, and it remains so until the very end. The finale won’t be a surprise, but a consistent and terrifying consequence of everything we’ve seen so far. But what did Ellison expect when moving into the house previously owned by a family massacred by an unknown perpetrator? Instead of pondering the identity of the killer, he should ask himself about their current whereabouts.