SHADOWCHASER: “Die Hard” in a Science Fiction Version

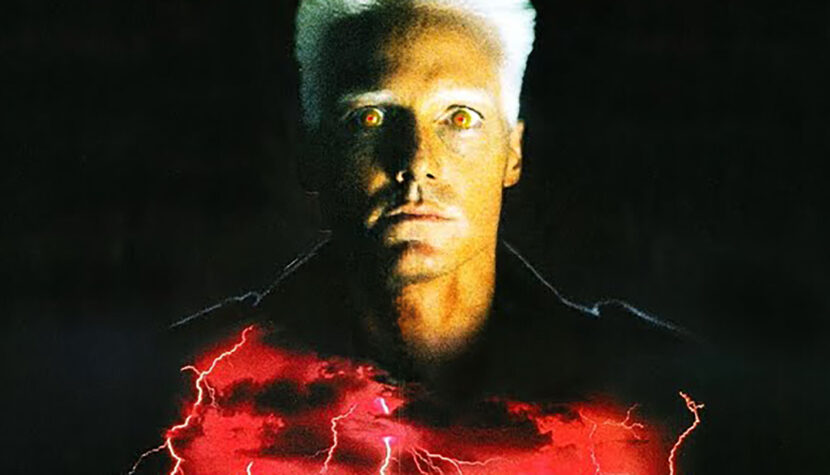

Romulus is the name of the main antagonist played by Frank Zagarino, known to VHS enthusiasts. I mention this because, due to the small budget, Shadowchaser used the set design from Alien 3, which contributed to the dark and oppressive aesthetic of the production while also saving it. The latest film in the Alien universe is titled Alien: Romulus. Quite a coincidence, and those set designs created for David Fincher’s film still impress, even when given an independent and low-budget life as in Shadowchaser. Nonetheless, it’s a film still worth watching, thanks to its highly concentrated dose of action and its nods to Alien, Blade Runner, and numerous motifs from Die Hard. It’s hard to believe, but someone dared to put the somber Frank Zagarino in Hans Gruber’s mask, and the dark Martin Kove in the role of John McClane. Amazingly, it didn’t turn into an unwatchable parody.

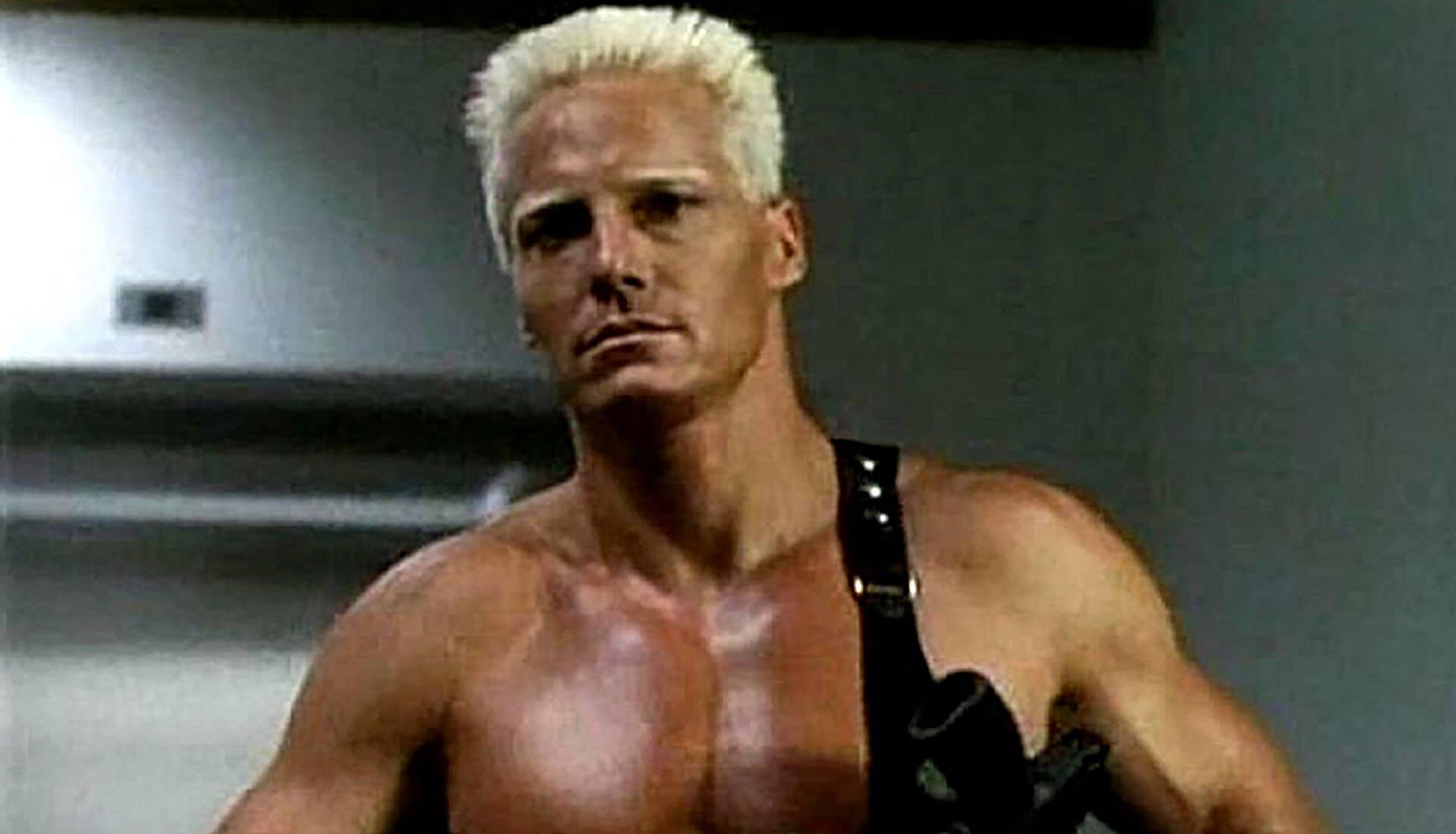

However, the film cannot be accused of plagiarism. It loosely interprets its inspirations within the context of B-movies, making certain motifs easily recognizable but not seen as unacceptable rip-offs. Shadowchaser was directed by John Eyres, a specialist in low-budget titles, who managed to create a fairly significant project called Monolith. In the realm of B-movies, this is almost a blockbuster, which cannot be said for the short and tragic story of the android Romulus. He wanted to break free, but he became a victim of human passion for war, much like Roy Batty in Blade Runner. He is not the main character in the film, though. The real hero, a flesh-and-blood character who is strong

and witty in dealing with terrorists, is the football player DaSilva. He is portrayed by Martin Kove, known to all fans of Karate Kid and Cobra Kai. It’s interesting to see this actor in such a positive and light role. Apparently, the lesson taught by Bruce Willis in Die Hard paid off, because if Shadowchaser had a bigger budget, Kove could have played the role of his life. As for the script: the creators really worked hard to develop a decent story. The twist of swapping the main character, who is a football player instead of an architect, sets the storyline until the end. The action also starts incredibly quickly. The android wakes up, kills the lab technicians, then suddenly appears in a hospital with a group of terrorists, and Die Hard in a VHS version begins.

The editing is sharp, the cuts quick yet very intuitive and clear, while the special effects are typical for low-budget action films rather than science fiction, especially with a killer robot as the main character. In this regard, viewers expecting thrilling sci-fi might feel shortchanged, especially since the finale features Martin Kove dousing himself with a certain drink as a form of advertisement. Although I praised the script, the ending is as poor as it can be. This is the biggest flaw of Shadowchaser. It’s also a shame that there wasn’t enough budget to show Romulus without his human guise, which would have required a significant amount of money. A burning shadow of the character against the backdrop of the night streets of a big American city had to suffice. This ambiguity can be almost seen as an artistic device and an opening for sequels. Indeed, three more sequels were made, but there is no continuity in the storyline, except for Frank Zagarino’s character, which is a pity. I feel there was a chance to create a series of coherent stories about an android that could have filled a niche not yet fully occupied by Terminator, which at that time had no real competition. Of course, this made Terminator more legendary, but also, soon—specifically by the turn of the century—it lost its cult status to become more of a franchise.

As always in these types of B-movies distributed on VHS, the music was created somewhere in a quiet home studio without the involvement of classical acoustic instruments. Costs, again and again, which is why it sounds as it does. It’s synthetic because in the ’90s, that was the easiest—grab a synthesizer, a track mixer, and a sequencer, punch in some notes, loop them, add octaves and a few inversions, and that’s it. The problem, however, is that in films from that era, this music was used excessively. The films usually screamed with it at every possible moment. There was no time for silence because the music intertwined with sound effects like gunshots, explosions, and in the case of Shadowchaser, peculiar servo noises. Romulus emits these sounds after taking a dozen or maybe dozens of bullets. So something grinds in his robotic joints from this extra lead. It has its charm because although the film adheres to the idea of SF, in practice, it lacks these typically aesthetic genre traits. Servo mechanisms appearing surprisingly are thus a nice fantastical accent.

I revisited this film years later in poor quality on YouTube. Another surprise for me was a role by Joss Ackland, as dark and vile as in Lethal Weapon 2. A rating around 4.5 seems appropriate for cinema of this era and its eclectically independent, cheap style. Shadowchaser is cinema with a wink, where you find a lot of sentimental motifs but also funny mistakes—sync issues, lack of sharpness, terrorists unable to hit anyone while shooting down a narrow corridor, etc. However, there is no pathos. There is action. It’s astonishing how, after years of considering cinema as one of the most important art forms for me, I’ve come to appreciate the simplicity of film expression without moral guilt being drilled into my brain cortex.