SEVEN PSYCHOPATHS. Simply brilliant…. and incredibly funny

However, that’s quite unfair – with all due respect to the pop culture conjurer – because the Irish creator has already vividly demonstrated with his Oscar-winning short film Six Shooter and In Bruges that he has developed his own, unique style, and Seven Psychopaths only confirms that emphatically.

McDonagh’s film tells the story of Marty Faranan, an Irish screenwriter creatively attacked by writer’s block. The man, immersed in his new project, has only its title – Seven Psychopaths. Drowning in alcoholism – of a kind that protagonists from Stephen King‘s books wouldn’t be ashamed of – Marty is fed stories about various psychopaths by his best friend, Billy – a dog thief. These stories are meant to help him develop the painfully emerging screenplay. However, life, as it does, suddenly comes to the rescue, and the theft of a maniacal criminal’s dog sets off a chain of events that will define the plot and characters of Faranan’s fictional work – with varying degrees of success for the world’s protagonists.

The straightforward plot of Seven Psychopaths quickly transforms into a brilliant experiment by the director. The story of the screenplay’s creation intertwines with the film itself. McDonagh cleverly utilizes the nested narrative structure, showing us films within the film and leading the narrative in a two-tiered manner. The first level presents the story unfolding in the present of the film and depicts the struggles of the characters with Woody Harrelson’s dog-loving gangster, while the second showcases fictionalized sequences of the characters’ ideas and stories, aimed at helping Marty create the titular psychopaths – allowing us, for example, to learn about the fate of a Vietnamese soldier and an eloquent prostitute or a twisted tale reminiscent of Bonnie and Clyde‘s exploits, with rabbits in the background. The director’s imagination works here at its highest creative levels, surprising with each plot twist, intelligently intertwining the aforementioned levels, breaking conventional elements of various genres – all the while maintaining coherence and narrative pace. Moreover, it’s bloody, sometimes overly exaggerated, but everything fits the overall concept and tastes excellent.

A lot of credit also goes to the dialogues, imaginative and not overstuffed with cinematic erudition by the author. Seven Psychopaths begins with a conversation about John Dillinger, The Godfather, and eyeballs, but it doesn’t delve into “Tarantinoesque” territories, where every scene of the film must somehow refer to the next dusty classic of the VHS era. The characters speak, of course, cooler than the average Joe, but there’s a certain emotional naturalness in their lines, making it easy to identify with them – although even in this aspect, the creator toys with the audience, forcing them to question their previous emotional investment several times.

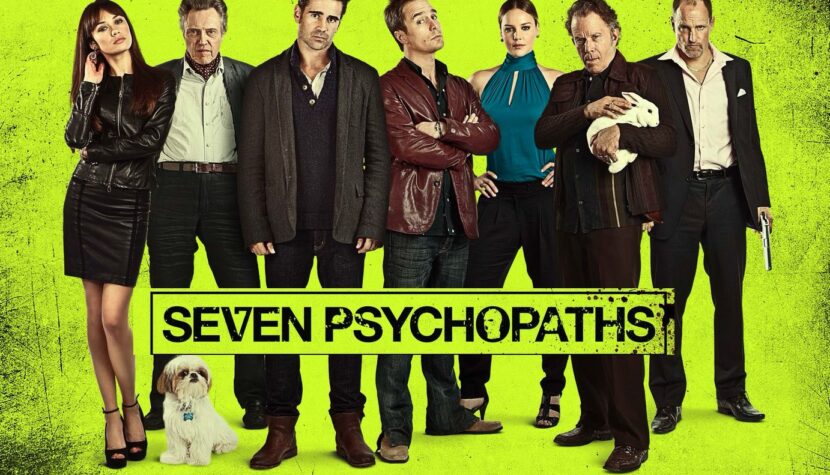

It’s the characters of Seven Psychopaths that are the strongest points of the film. The casting was done perfectly, and almost every actor utilizes their screen time with cosmic finesse. The chemistry between Farrell-Rockwell-Walken is beautiful. The Irishman seamlessly blends into the background – just like a real writer practically becomes an invisible observer, who watches with disbelief the world he has created, while “dancing” around him are unrestrained characters akin to psychopaths. In all this chaos, however, he is the least cartoonish character – with a problem that develops as a character and becomes an accessible surrogate for the viewer – at a time when the rest of the characters are characteristic pawns skillfully placed by the screenwriter.

Rockwell’s and Walken’s performances are on opposite emotional poles. The former is a volcano of energy, who behind his idiotic facade hides a certain determined philosophy. He embodies the modern American film producer, for whom an action movie without blood is no movie, and even in the middle of the desert, something has to explode. Meanwhile, Christopher Walken plays with his legendary stone face, without falling into parody. His character is solidly outlined and, despite suppressing emotions, opens up the most of the entire cast assembled by McDonagh.

The leading trio of actors is greatly boosted by the aforementioned Harrelson (who can change our attitude towards the character in a fraction of a second). Also, Tom Waits’ cameo is delightful, reminiscent of the best times of his collaboration with Jim Jarmusch. Only Olga Kurylenko, so prominently featured on the poster, appears for just a few minutes – which is well explained by her role in Faranan’s work.

Overall, Seven Psychopaths is great – an original gem of contemporary cinema amidst a sea of poor glass pebbles. McDonagh has forsaken, this time, telling the story mainly through the setting and its atmosphere – as in the case of In Bruges – opting instead to delve into the intricacies of the screenwriter’s mind and play with the mechanics of cinematic storytelling. It’s a wonderfully funny, surprising, and thrilling adventure that simply must be seen in the cinema. And the most honest buddy movie since Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. If I were to return to that unfortunate comparison with Quentin Tarantino, the Irish director has made his Pulp Fiction after the Belgian Reservoir Dogs – and for the first time in ages, I found myself crying with laughter in the cinema.