PROXIMA: A Mother’s Heart in Space

When you go to see a film about a female astronaut preparing for her first mission, you might expect a blockbuster with a feminist message. However, “Proxima”, by Alice Winocour, is a far more complex work, woven from a range of emotions. While, yes, there are occasional “girl power” moments, the film is much more often about something far more primal – maternal instinct.

It’s been a long time since I’ve seen motherly love portrayed as poignantly in cinema as it is in “Proxima”. The film, set in a subject matter usually tackled by big-budget Hollywood productions, is at the same time remarkably intimate and insightful, revealing the full spectrum of emotions and experiences that accompany the astronaut on her maiden mission. Sara (the always excellent Eva Green) is great at what she does – she loves her job, and the honor of participating in a mission to conquer space is the crowning achievement of her career. But when we meet her in the opening shot of “Proxima”, she is not primarily an astronaut but a mother – and it’s this life role that consumes her the most. Sara shares an incredibly close bond with her daughter Stella (the wonderful Zélie Boulant), who seems very mature for her school-age years, though it quickly becomes clear that this is only an illusion. The closer the space mission’s launch approaches, the more Stella rebels against her mother’s decision. She wants to, but can’t understand why the most important person in her young life is choosing to leave her for several months.

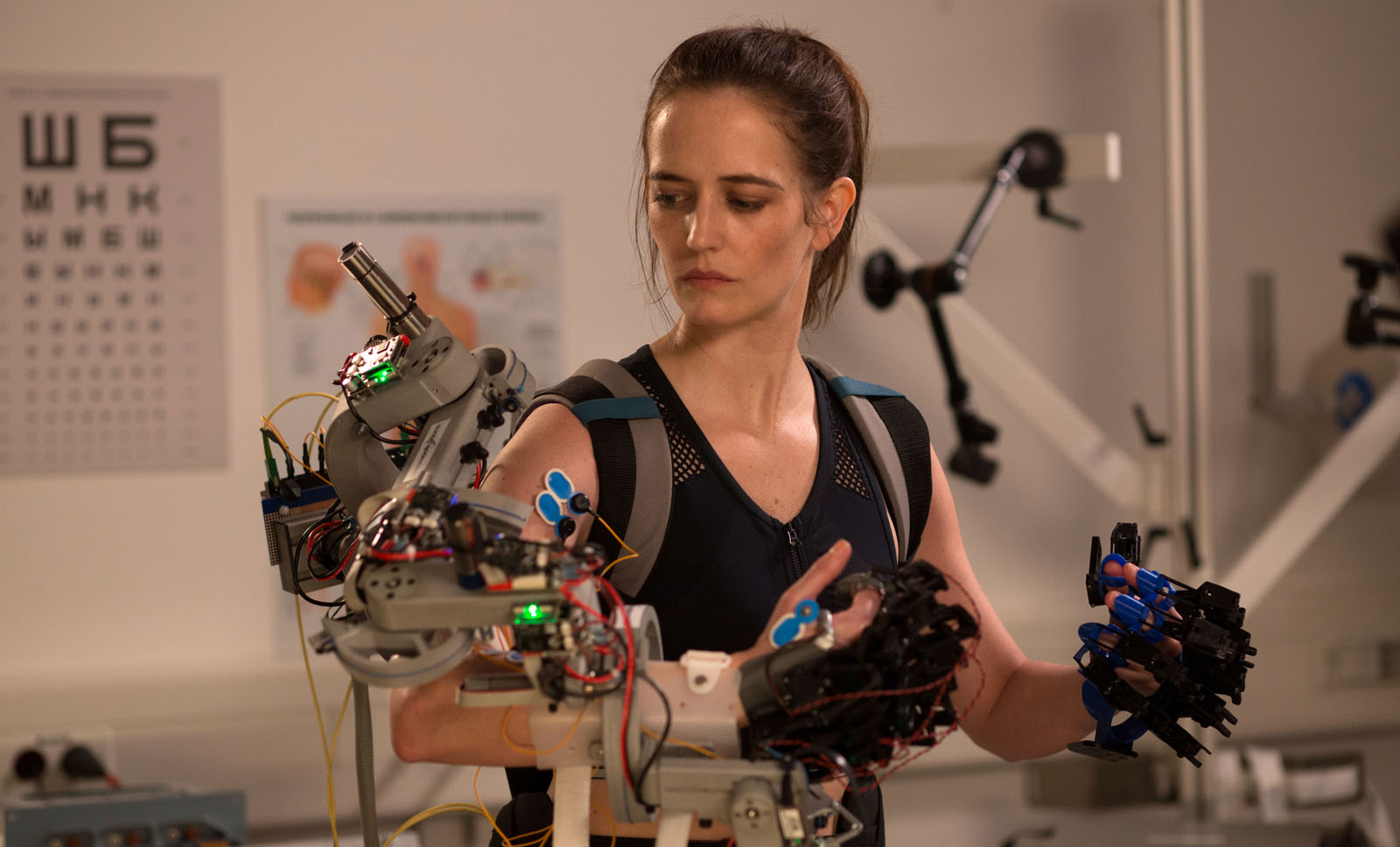

Winocour’s greatest triumph, despite having only two full-length films under her belt, is avoiding clichés. This story could easily have been reduced to a shallow family drama, where scenes of a child’s rebellion are interspersed with alternating bouts of parental anger and helplessness. Fortunately, the French director approaches the issue with sensitivity, which, given her previous screenplay for the excellent “Mustang” (2015), is not particularly surprising. Sara navigates between the desire to fulfill her dream, professional duty, parental responsibility, and pure motherly love – all while undergoing grueling training at a Russian space base. Her mental exhaustion is thus compounded by physical fatigue. Emotional outbursts could have easily fit into this scenario, but Winocour steers clear of that path. Instead, she allows her protagonist to find her own balance between wild ambition and equally overwhelming love for her daughter.

Crucially, the emotional layer of the film doesn’t entirely overshadow the technical aspect of the story – Winocour meticulously depicts the astronauts’ preparation period for their mission to the International Space Station, making the journey itself even more interesting for the viewer. We not only dive into Sara’s intimate experiences but also into the intricacies of astronaut work, which is portrayed here in a far less glamorous manner than in Hollywood blockbusters. In “Proxima”, the mission itself isn’t the most important aspect, but rather the journey leading up to it – both the physical and emotional one. As we witness the protagonist’s struggles with the limits of her body and the burdens on her mind, we gain an understanding of just how incredibly difficult the job of an astronaut is. If the scene of Cooper saying goodbye to his daughter in “Interstellar” broke your heart, Winocour’s film will move you even more, especially as “Proxima” feels much closer to real life than Christopher Nolan’s epic.

Alice Winocour’s insightful, deep work is something of an “anti-blockbuster,” a counterbalance to the superficiality of big-budget productions. “Proxima” doesn’t reject the conventions of a spectacular sci-fi film but offers its own, intimate approach to the subject while avoiding trivialization. Although on paper Winocour’s film may not seem particularly impressive, it strikes both the heart and the mind.