NEON GENESIS EVANGELION and END OF EVANGELION. Existential anime… with mechs

It’s difficult to write about something that has already been discussed extensively and stirs such extreme emotions. For some, Neon Genesis Evangelion is a legend, one of the most original and deeply moving stories ever told, while for others, it’s the best example of pretentious, postmodern gibberish and an example of how not to construct characters if you don’t want to frustrate and annoy viewers. Without a doubt, it is a work considered highly significant in the history of Japanese animation, a work that turned the mecha genre and animated science fiction in general upside down and showed how popular conventions and formulas could be used to create something entirely new, strange, and very, very complex. It is an anime that every enthusiast of this form of entertainment and art should be familiar with. More broadly, anyone even slightly interested in the Land of the Rising Sun should know something about it because Neon Genesis Evangelion has deeply rooted itself in Japanese pop culture. References to it can be found in other anime and manga, games, songs, and advertisements. Themes and scenes from it are widely known and quoted. So, in practice, anyone reading texts about anime here, who has not yet experienced the life’s work of Hideaki Anno, should at least take a look at it to know “what all the fuss is about.”

Neon Genesis Evangelion as a psychiatric ward

For some of you, just taking a look will be enough, and the series may discourage, tire, and depress you. And there will be absolutely nothing strange about it, as this is one of the heaviest things that Japanese animation has created, a work designed to depress and confound the viewer, full of implications and ostentatiously vague. Traumatized to the extreme, unable to cope with themselves, the characters, their constant existential crises, doubts, and breakdowns, create an impression that you are visiting a psychiatric ward. All these mysterious threads, the solution of which is even more enigmatic, this enormous amount of Judeo-Christian religious references (Evangelions, Angels, Adam and Lilith, Lance of Longinus, Dead Sea Scrolls, Kabbalistic Tree of Life, Gates of Guf, cross-shaped explosions) about which it is unclear how seriously to take them – which ones were introduced because they looked exotic to the Japanese, and which (if any) carry deeper meaning. For some of you (I won’t hide that for me too), these deeply disturbed and imperfect characters may turn out to be very interesting and surprisingly close, and the narrative and symbolic labyrinth fascinating. It may turn out that Neon Genesis Evangelion will shake you like few fictions and make you delve into its mythology in search of the meaning and purpose of the suffering that the Angels and the secret organization SEELE are subjecting Shinji, Asuka, and others to. It also makes you reflect on the suffering whose sources lie in the shattered, contradictory, and incomprehensible nature of humanity itself.

A plot

Four and a half billion years ago, a collision between Earth and a mysterious object gave birth to the Moon and gave our planet its current size and mass. Astronomers refer to this event as the Giant Impact.

On September 15, 2000, a meteorite, too small to be detected and too fast (95% the speed of light) to be stopped, struck Antarctica. The force of the impact, associated with such tremendous velocity, melted glaciers and altered the Earth’s axial tilt. Floods and tsunamis claimed two billion lives, while famine and a lack of space for refugees led to wars between neighboring countries worldwide. When equipped with special UN prerogatives, the United Nations managed to end the conflicts and initiate the rebuilding of civilization. However, half of humanity had already perished, and climate diversity was lost forever. This largest catastrophe in human history was named the Second Impact.

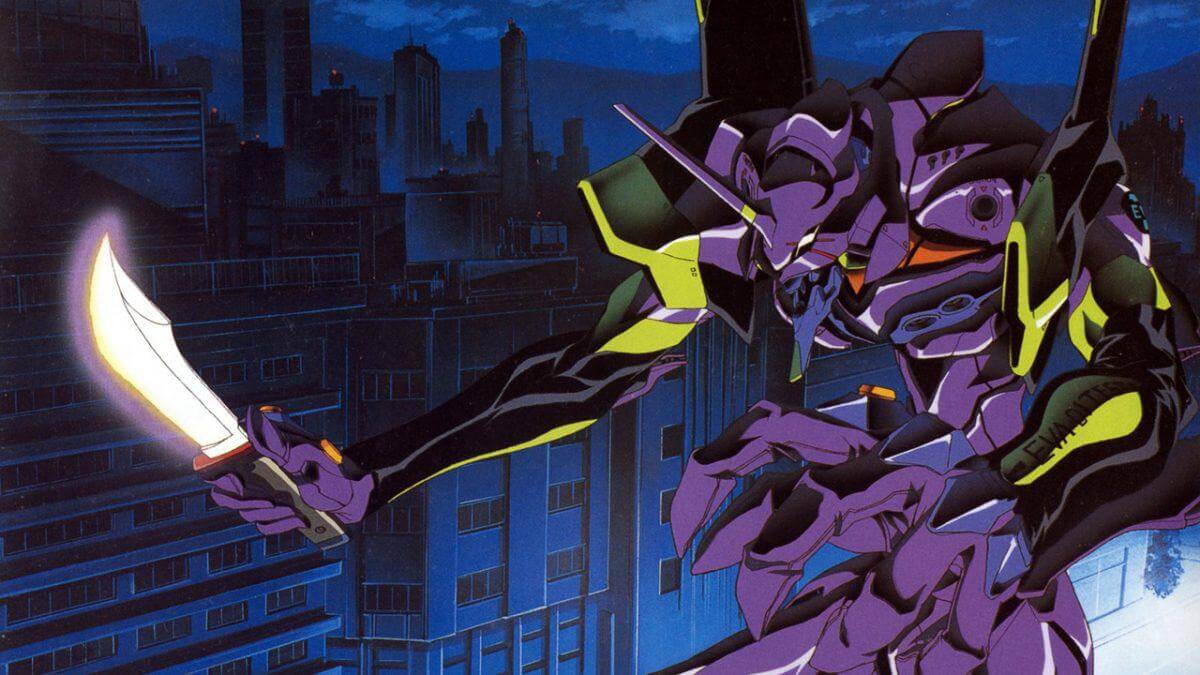

Fifteen years later, Japan, which had been raised from the ruins, is attacked by giant beings known as Angels, resistant to all forms of weaponry. However, the authorities appeared to be aware of the threat of invaders in advance and were not entirely unprepared. NERV, the United Nations scientific special agency, had secretly constructed the most powerful weapon available to humanity – “Multipurpose Humanoid Fighting Machines” called Evangelions. These gigantic robots have a particular flaw – they can only be piloted by individuals born after the Second Impact. The first Angel attack on Tokyo-3, where NERV’s base is located, coincides with the arrival of Shinji Ikari in the city, the son of the organization’s chief. Summoned by his father, the timid boy learns that he is one of a few 14-year-olds selected to pilot the Evangelions. Shinji, however, seems to be the last possible candidate for a heroic mecha pilot – traumatized by his mother’s death and abandoned by his father, the teenager is almost completely lacking in self-confidence, unable to make decisions or cope with stress. Initially, he reacts with fear and is unable to bring himself to enter the massive machine. Only the sight of another injured pilot, whom his father intends to send into battle, changes his mind. To everyone’s surprise, especially Shinji’s, the battle ends in his victory, mainly due to the extraordinary behavior of the Evangelion, which seems to possess its own will and actively protects its pilot.

And so, young Ikari is reluctantly thrust into the role of humanity’s defender, shoulder to shoulder with two equally ill-adjusted female comrades, the autistic Rei and the rivalry-obsessed Asuka. They fight against the mysterious invaders, each of which has an increasingly bizarre form and greater power. Each of these beings carries the threat of the Third Impact, for if any of the Angels fully unleashes its power, a catastrophe similar to the one in Antarctica will occur, and life on Earth will face complete annihilation.

The battle against these extraordinary foes becomes an opportunity for Shinji to confront his deepest weaknesses and fears, with pain and loneliness, on a cleansing yet incredibly challenging journey of self-discovery. The viewer gradually realizes that this journey into the depths of the characters’ psyches is more important than the battles of giant robots. All the critical mysteries of the series, the nature of the Angels and Evangelions, the true causes of the Second Impact, the colossal entity held in the deepest underground of NERV’s headquarters, are somehow linked to the problems of human existence and human imperfection.

These connections become clearer when it finally dawns on us (and the characters) that the entire intrigue, the entire war against the Angels, is just a cover for a conspiracy on an unimaginable scale, a plan for the radical and complete transformation of all humanity without asking for its consent. This transformation may free our species from pain, loneliness, and death, but it will mean the destruction of homo sapiens in its current form and the devastation of the entire planet. The key role in this transformation is to be played by Shinji Ikari.

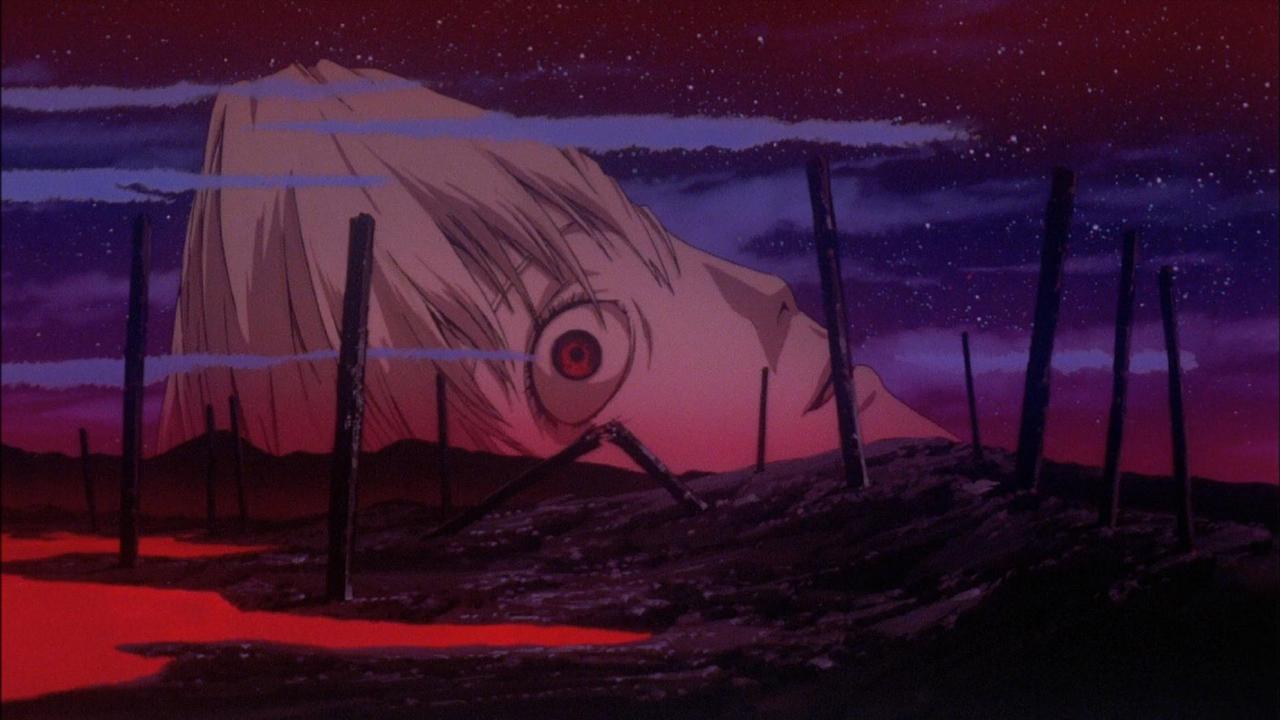

Neon Genesis Evangelion series as a whole is unconventional and not easy to digest, and its (in)fame as a psychedelic experiment that disregards viewer expectations is primarily owed to its ending, or rather, its two endings. Both the surrealistic episodes 25 and 26, which take place within the minds of Shinji and other characters, and the alternative apocalyptic film End of Evangelion, created a few years later, raised the bar for the audience by ten meters. They demanded that viewers pay attention to every word spoken by the characters and delve even deeper into the strange and, in the case of the movie, often very unsettling images.

For any attentive viewer, it will be clear that both endings are crucial to understanding the entire Neon Genesis Evangelion story, the eschatological conspiracy of SEELE, and the destinies that lie before the characters. They also shed light on the decisions and choices that every human individual faces, something that the “working through his depression” author (screenwriter, director, and producer) Hideaki Anno draws attention to.

Advanced psychoanalysis

The latter will be clear to viewers familiar with names like Freud, Jung, Fromm, or Lacan and the contributions they made to understanding the intricacies of the human psyche. These viewers will immediately recognize that Neon Genesis Evangelion is a grand cinematic psychoanalytic treatise, possibly the most perfect in the history of film and television. This is not about psychoanalysis at the level of phallic symbols and “penis envy” (though erotic tension between some characters plays an important role here, and End of Evangelion is rich in sexual symbolism), but rather about its deepest, existential dimension. It’s about the vision of man that arises from psychoanalysis – a weak and absolutely lonely being that will never be able to fully understand or be understood by another human being and will never be genuinely understood itself. Beings condemned to eternal conflict between the desire for independence, necessary to build one’s own “self,” and the need for belonging and acceptance. This conflict is compounded by the simple fact that the only way to create a stable self-image is through continuous confrontation with the world and constant reflection in the eyes of others. These beings are perpetually tempted to escape from freedom and responsibility, to flee from the fear and pain that comes with being a separate individual, a flight that often leads to the loss of one’s own will and personality.

Neon Genesis Evangelion and End of Evangelion brilliantly depict all of this, emphasizing the universal dimension of psychoanalytic dilemmas and achieving a truly genius narrative feat. They place the decision to resolve these problems for all of humanity in the hands of a character. For this character, the choice between escape and facing life, between dissolving into the collective mind and experiencing loneliness as a separate entity, represents the fundamental issue of his psyche.

Production values of Neon Genesis Evangelion

This philosophical weight in itself would be enough to make Neon Genesis Evangelion one of the most important anime ever created, but there are other equally significant aspects. Such as the fantastic design of the giant robots and their adversaries, the music, with the catchy song Zankoku no Tenshi no Teze alongside the brilliant use of classical music (Asuka’s intense battle with the “harpies” set to Bach in End of Evangelion, or the final Angel bidding humanity farewell with Beethoven’s Ode to Joy in the series, are moments that have gone down in history). There are also the fascinating scenes of visions experienced by the characters – Rei’s Poem is still one of my favorite film scenes. The exceptional seiyuu whose talent shines particularly bright when compared to their American counterparts. The provocative play with the erotic fantasies of male viewers, culminating in the shocking opening scene of End of Evangelion, which can be seen as Anno’s powerful blow to the face.

While the animation in Neon Genesis Evangelion series may have aged (it was never particularly impressive due to budget constraints), and the brutality and nightmarish images in End of Evangelion may not make as strong an impression on viewers who have experienced more recent works (such as Elfen Lied, Higurashi, Mnemosyne), the power, depth, and innovation of this story have not diminished in the least. Anno’s work recently returned to the forefront of Japanese animation with the Rebuild of Evangelion film tetralogy, which retells the entire story. The first two installments are among the most significant anime events of recent years. However, the enjoyment of watching these excellent films will not be complete without knowledge of the original series. So, there is yet another reason to watch this legendary series – to immerse yourself with a group of lost children and equally lost adults in the depths of oneself and seek answers to questions that no one else can answer for us.