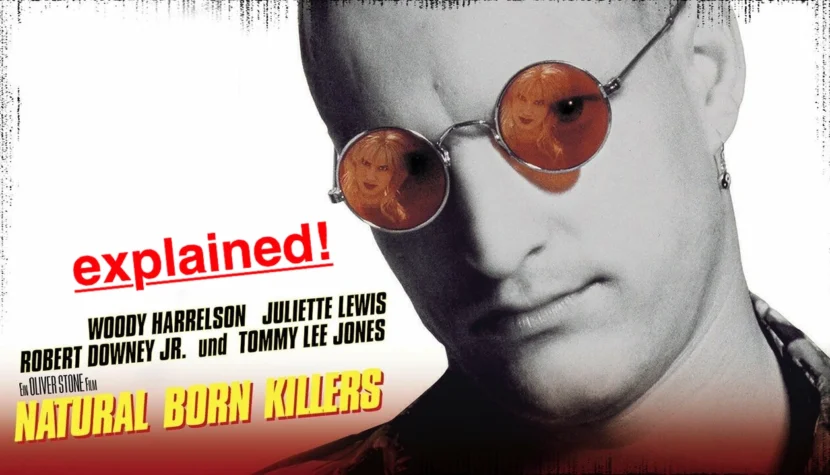

NATURAL BORN KILLERS. Stone’s Controversial Opus Explained

It is sometimes criticized for its extremely intense portrayal of violence, almost akin to glorification, while other times it is dismissed as being unworthy of consideration because the depiction of violence serves no purpose other than providing dubious entertainment value, making the film merely a well-made action movie.

TOO MUCH TV

However, depicting the characters’ psyches is not the only reason for the film’s extraordinary appearance. Just as the expressive form in Ulysses shatters the classical image of the world as an ordered cosmos […] definitively defined by the rules of Aristotelian-Thomistic logic, and the montage in Battleship Potemkin achieves the significance of a philosophical declaration and expresses a materialistic vision of reality and the relationship between man and his environment, so too does the visual aspect of Natural Born Killers serve as a critical commentary on contemporary times and the role media play in them.

In his commentary on Natural Born Killers, the creator of Platoon confesses that, like many others in America who were born during the post-war baby boom, he has a somewhat paranoid attitude towards the media. Belonging to a generation that grew up during the Cold War era and was constantly frightened by the Enemy threatening the “American way of life,” Stone—taught to be afraid—sees a new threat in the mass media. His concerns, though perhaps expressed somewhat exaggeratedly, are not just another typical example of the conspiracy-theory-ridden American consciousness. No one can deny that the media are associated with many serious problems, one of the most significant being their impact on our perception of the world, including various social phenomena. This is especially true for television and similar media, as they have the most powerful influence due to their engagement of multiple senses at once.

How does television change our perception of reality? It does so by trivializing virtually all aspects of social life that it decides to show.

As Neil Postman stated, Entertainment is the supra-ideology of all discourse on television. No matter what is depicted or from what point of view, the overarching presumption is that it is there for our amusement and pleasure. This “overarching presumption” is related to the fact that television conveys its content mainly through images, which “appeal not to reason but to emotion,” since—unlike print—it contains no ideas, shows only an object, ripped out of context and devoid of meaning. By making entertainment its “natural format,” the television medium trivializes not only subjects that can be lightly treated by their very nature but also those that require more time and thought than is devoted to them in evening news shows or less-than-hour-long talk shows interrupted by commercials. One of these significant topics is undoubtedly all kinds of violence, and it is precisely this trivialization of violence by television that Stone attacks through the form of his film.

Among all the scenes that make up Natural Born Killers, there are two that are most important to the actual message of the film: the sitcom I Love Mallory, with the scene of the murder of the girl’s father (a scene that, although separated from the sitcom by the sequence in the jail, continues its aesthetic to some extent) and the scene in the motel.

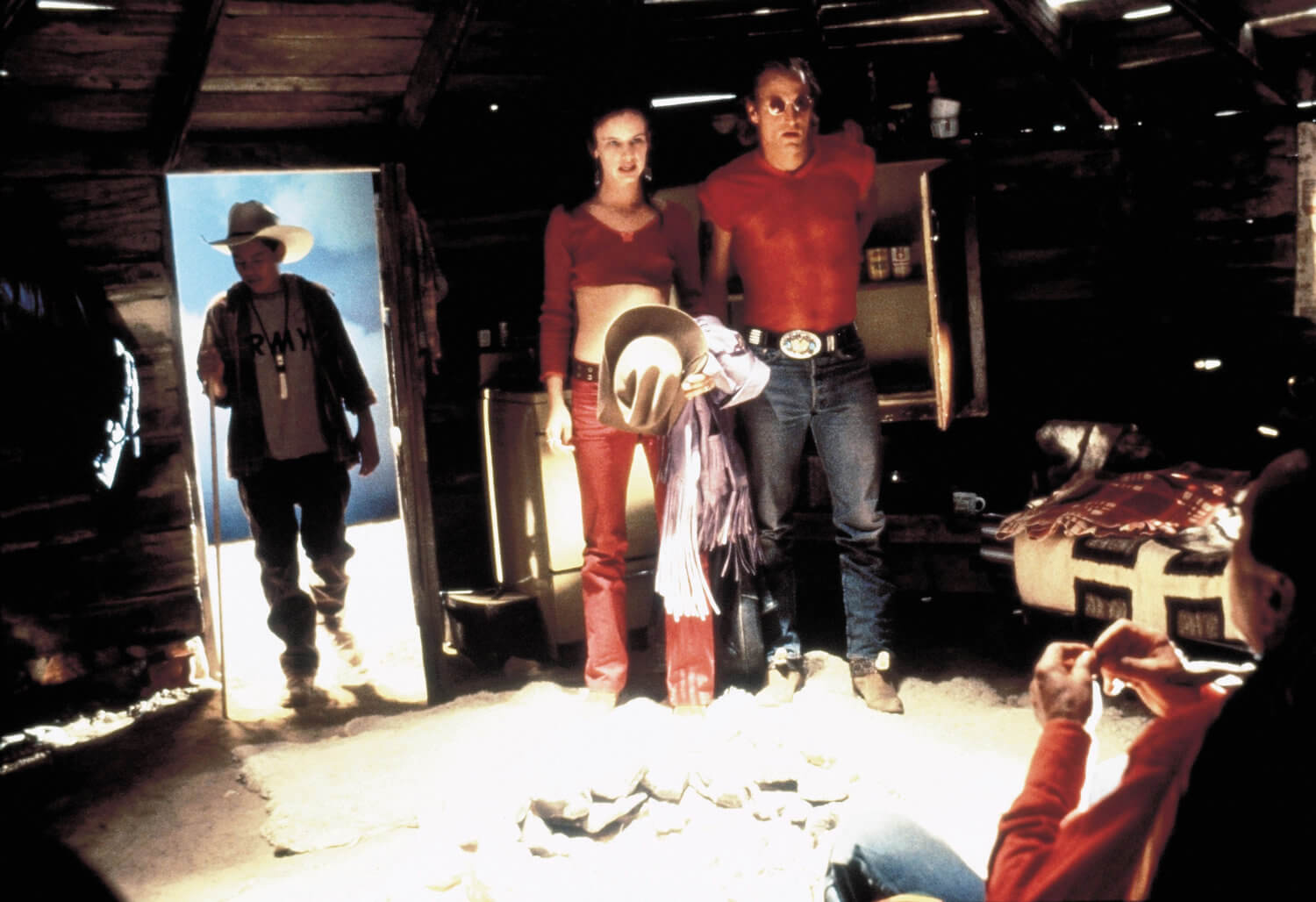

A scene in the style of an American sitcom from the fifties, with its characteristic dubbed laughter, the characters’ self-awareness as show heroes and their garish clothing, shows the first meeting of the murderous couple in Mallory’s family home. So we see the disgusting scumbag father (Rodney Dangerfield), who, between molesting his daughter, spends all his time in front of the TV with a beer in his hand. We see a hysterical mother (Edie McClurg) with an appearance as trashy as the interior of her home, who knows about her daughter’s molestation, but whether from the impotence to oppose her husband or simply from moral indifference – she does nothing about it. We see Mallory’s malicious brother (Sean Stone) and finally Mallory herself – a teenager trapped in this pathological hell, for whom “the only release is television” reflecting her “shallow mentality”.

Despite the vulgar, hateful, and offensive nature of the conversations among these macabre characters, each remark and retort is accompanied by recorded audience laughter, turning the horrific scene of verbal (and not just verbal) violence into a perfect joke. Thus, the sitcom convention trivializes the mutual destruction of people, a problem faced by countless households worldwide, reducing it to a clichéd, laugh-inducing banality.

I Love Mallory is therefore a satire of all sitcoms that have appeared on screens since the inception of television, and more importantly, it serves a revealing function with respect to them.

As Heidi Nelson Hochenedel states, sitcoms have a long history of trivializing images, and she cites The Honeymooners, one of the first sitcoms ever to appear on television, where Ralph constantly belittles Alice, threatening to hit her (To the moon, Alice, to the moon!), which is portrayed in a highly humorous manner.

However, this is not just about sitcoms and the television that produces them—Stone’s critique extends beyond those who create contemporary mass culture to the audience that is susceptible to its content. This content could not develop and proliferate without finding a receptive audience. As viewers, we have long stopped flinching at the violence packaged attractively by television—in fact, we often eagerly accept it as such. Stone emphasizes this in the scene of Mallory’s father’s murder, on one hand presenting it visually in an extremely brutal way, while on the other hand overlaying it with a soundtrack reminiscent of Tom & Jerry cartoons, where the plot typically revolves around the animated protagonists inflicting pain on each other. He assesses the detrimental effects of television on viewers’ sensitivity not directly through the script, but through the form—embedding his opinion in the contrast between image and sound.

The critique by the creator of Nixon is fully developed in the motel scene. Here, we see the pair of murderers making love on a bed. Behind them, in the background, there’s a large window displaying archival footage including Hitler, Stalin, the Vietnam War, ecological devastation—a panorama of violence from the past century. However, Mickey and Mallory don’t see this—they are absorbed in the artificial violence flickering on the screen of their motel TV, snippets from Hollywood films like Scarface and Midnight Express.

In this scene of Natural Born Killers, Stone encapsulates the idea that the couple of murderers are essentially a product, flower, spoiled fruit of the 20th century, which was the most violent century in all of human history.

The reason they don’t perceive the real cruelty outside the window is their complete insensitivity stemming from their familiarity with acts of violence they have been watching on television since childhood.

Their distorted way of understanding the world, especially their capacity for killing, is not merely a result of pathology within their family homes, but also the continuous perception of reality through the prism of the TV screen. In the film, this realization is understood only by the old Native American shaman they encounter shortly before being imprisoned: The Indian sees them through and through, knows who they are, and his diagnosis is displayed on their chests in the form of glowing letters proclaiming: too much TV. Here too, the truth about Mickey and Mallory is expressed solely through imagery.

But is Stone’s assertion that media have a negative impact on the viewer’s relationship with cruelty and death somewhat exaggerated?

The answer becomes obvious when we consider all the infamous murders committed in 1994 and later—mainly in the United States and Great Britain—that were inspired by Natural Born Killers! Here lies the entire misfortune and irony suffered by this work and its creator—a film intended to critique the glamorization of violence eventually became the subject of such critique itself. Stone used many techniques to remind viewers of the sheer fiction of what happens on screen: the death of the cook seen from the perspective of a bullet shot between her eyes, a slow-motion view set to an operatic aria of a knife plunging into a cowboy’s back, or the face of Warden McClusky seen through the hole in Gale’s shot-through hand—each of these comedic threads was meant as a wink from the director to remind us that what we are watching is not real and that murder committed in reality is something entirely different from murder in a film.

Unfortunately, contrary to Stone’s intentions, the admonitions woven into the formal fabric of Natural Born Killers were not properly interpreted by many, and the strength and charisma of Mickey and Mallory determined the interpretation instead.

HALF-BRAINS FROM THE ZOMBIE PLANET

After Natural Born Killers, Oliver Stone repeated the form he created there once again—in Nixon. Similar to the exploits of the killer couple, the biography of one of the most controversial presidents in the history of the United States was presented in the form of a collage of various film techniques, black-and-white and color photographs, extraordinary camera perspectives, archival films, and so on. However, this time the film’s form turned out to be merely art for art’s sake—although it was a feast for the eyes and another undeniable proof of Stone’s great talent, it did not contain any additional meanings beyond those present in the film’s script itself. Hence, it’s no wonder that after the premiere of Nixon, critics focused mainly on the portrayal of the president’s character, limiting comments on the film’s visual side to acknowledging its creator’s skillful mastery of his craft.

However, as observed in the examples I have provided, Natural Born Killers was a completely different case—the form of this film was expressive par excellence: not only did it represent the inner world of the film’s characters, but it also conveyed messages that were not explicitly stated in the film, yet were the essence of what was happening on screen—namely, the trivialization of violence by the media and thus the spreading of so-called “social desensitization” towards cruelty and its victims. Why these contents were not noticed—I have already tried to answer that.

To summarize, however, I will repeat that the direct reason was probably the too obvious emphasis on the attractiveness of the main characters, their invincibility against the system chasing them, and the suggestively depicted scenes of violence in which killing another person is shown as something very easy and attractive at the same time.

Another reason for the viewers’ disregard of the extraordinary form of Natural Born Killers could also be that this form did not necessarily appear extraordinary to them.

As I mentioned at the beginning of the article— for many, it was merely a blood-soaked, nearly two-hour-long music video. There’s nothing strange about that: after all, as a whole, Stone’s film form mimics the television image—constantly changing, filled with snapshot, loudly colored shots—an image that the vast majority of humanity gazes at day and night.

The film by the creator of JFK reflects this kaleidoscopic mush, whose numbing character Wayne Gale aptly captured in response to his editor’s remark that the same shots were repeated in successive episodes of American Maniacs: Half-brains from the zombie planet remember nothing. It’s cheap brain food. Filler. That’s how Stone’s work was also treated—as another aesthetic extension of television pap to which we have long been accustomed.

Words: Marcin Wilczynski