LIQUID SKY. There’s No Other Film Quite Like It

High on crazy drugs and for next to no money, a film by Soviet emigrants paying tribute to the New York club scene while possibly mocking the pretentious art scene of the city. One thing is certain: there is no other film quite like Liquid Sky.

Margaret is a young model living in New York with her friend Adrian, an avant-garde performer and drug dealer. Her life revolves around photo shoots, nightclub visits, cocaine use, and engaging in sex (with both men and women). A similar existence is led by Margaret’s rival, Jimmy, a heroin addict and the son of a wealthy TV producer. One night, a flying saucer the size of a dinner plate lands on the rooftop of Margaret’s building. A German scientist determines that bodiless aliens have come to Earth in search of sustenance – the endorphins produced by humans during drug-induced euphoria and orgasm. Margaret discovers that her lovers die suddenly with a crystalline tube in their heads, and when she connects their deaths to sex, she begins to exploit it for her own purposes.

In the early 1970s, Russian filmmakers Slava Tsukerman and his wife Nina Kerova emigrated from the USSR, first to Israel and then to the USA. In 1976, the couple settled in New York, where they began working on a screenplay titled “Sweet Sixteen.” When financing for the film proved impossible, Tsukerman and Kerova focused on separate projects: he started writing a story about an alien invasion, while she came up with a tale about a woman unable to achieve orgasm. Soon, both ideas were merged with the help of Anne Carlisle, a friend of the couple who was cast in the dual roles of Margaret and Jimmy. Other key contributors to the production included Yuri Neyman (cinematography, special effects), Marina Levikova (costumes, set design), and Clive Smith and Brenda Hutchinson, who composed the synthesizer-based soundtrack.

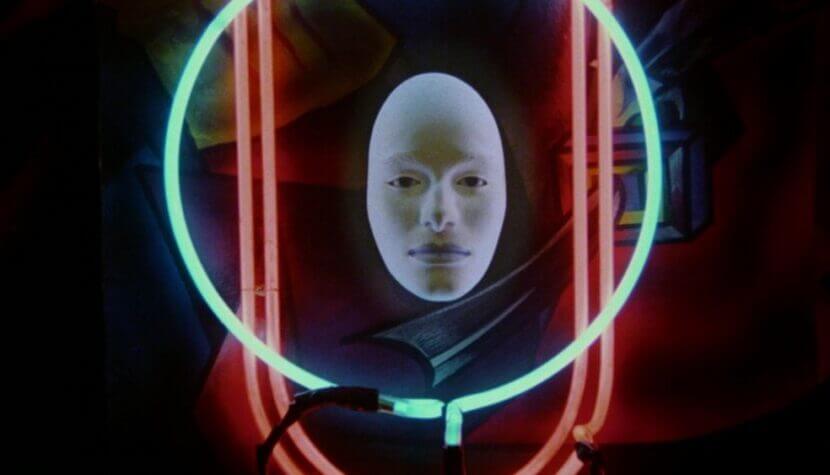

Liquid Sky is a truly astonishing and original film, from its guerrilla-style production conditions to its unconventional form and its profound (though not fully conscious) influence on popular culture. Visually, it is a sensory delight: pastel neon lights illuminating the interiors of austere apartments and nightclubs, colorful costumes and imaginative hairstyles, the outlines of New York skyscrapers against a bright orange sunset, the monolithic form of the Empire State Building resembling a giant syringe pointed towards the sky, and the psychedelic perspective of the aliens, which must have inspired the creators of the five years younger film “Predator” by John McTiernan. This retrofuturistic fashion show is admired for the team’s ability to compensate for a limited budget with boundless imagination.

Similarly significant (and equally remarkable) is the soundtrack generated using the Fairlight CMI, an incredibly expensive and complex synthesizer with sampling capabilities at the time. Initially, the creators wanted to collaborate with Brian Eno, a former member of Roxy Music and a pioneer of ambient music. When that didn’t work out, they enlisted acclaimed composers Clive Smith and Brenda Hutchinson, who arranged several classical music pieces (including Carl Orff’s) on the mentioned Fairlight synthesizer at Tsukerman’s request. The result was a modern electronic interpretation of classical music. The sounds emitted by the aliens were created using wind chimes, metal, glass, and wood. Minimalistic music and sound architecture play a significant role in the film, intensifying its unsettling atmosphere.

This is essentially a typical midnight movie – a low-budget film with mediocre acting and a pretextual plot, circulating in independent distribution and the festival circuit, devoid of major promotion, and therefore destined for late-night screenings. Yet, it resonated with a certain segment of the audience and quickly gained cult status, not after many years of obscurity but almost immediately. With a production budget of $500,000, it earned nearly three times that amount in the USA alone within a few months of its release. “Liquid Sky” also found success in Germany and Japan, and today its influence is felt not only in cinema (e.g., “The Dark Angel” by Craig R. Baxley, “Beyond the Black Rainbow” by Panos Cosmatos, “Enter the Void” by Gaspar Noé, etc.) but also in music. The ephemeral genre known as electroclash and the associated fashion were heavily inspired by Slava Tsukerman’s film.

“My main idea for ‘Liquid Sky‘ was to create a parable that would encompass most of the trendy, mythical themes of that period, such as sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll, violence, and aliens from outer space,” explained the director. In hindsight, his film can be interpreted in various ways: as a snapshot of New York’s bohemian life in the 1980s, a portrait of the new wave scene born from post-punk and glam rock (David Bowie clones regularly appear on screen, and the androgynous Margaret explicitly references him), and perhaps even a sinister foreshadowing of the AIDS epidemic that equated drugs and sex with death. It’s possible that Tsukerman’s campy film is a sharp, sarcastic, and darkly humorous satire of decadent artistic circles. Or maybe Liquid Sky is as empty and superficial as the hollow people it depicts? That’s a question each viewer must answer for themselves.