FANTASTIC PLANET. Visionary, fresh, unique. Marvel of a sci-fi

Considering the available budgets and possibilities, it’s possible to adapt practically anything for the screen. There’s no need to create entirely new worlds from scratch—just delve into the stack of as-yet-unutilized fantastic literature. And there’s certainly no shortage of that. Yet, let’s look at the upcoming releases of broadly defined science fiction films. If we exclude franchises, sequels, spin-offs, reboots, remakes, etc.—how many titles remain? Established and familiar themes, financially safe solutions offering undoubtedly high-budget entertainment, but not necessarily groundbreaking. Adding more installments to popular titles enriches producers’ coffers, while fans’ shelves bend under the weight of disc collections. This fantasy seems to be becoming less and less fantastic.

Fortunately, there’s an antidote in the form of animation. It requires lower costs and allows creators to be independent of major studios. Moreover, animation techniques themselves can be works of art that inscribe themselves in the cinematic canon and go down in history. By reaching for animation, one can come across astonishingly relevant, skillful, and captivating productions. A great example is Fantastic Planet (dir. René Laloux), awarded the Special Prize at Cannes in 1973.

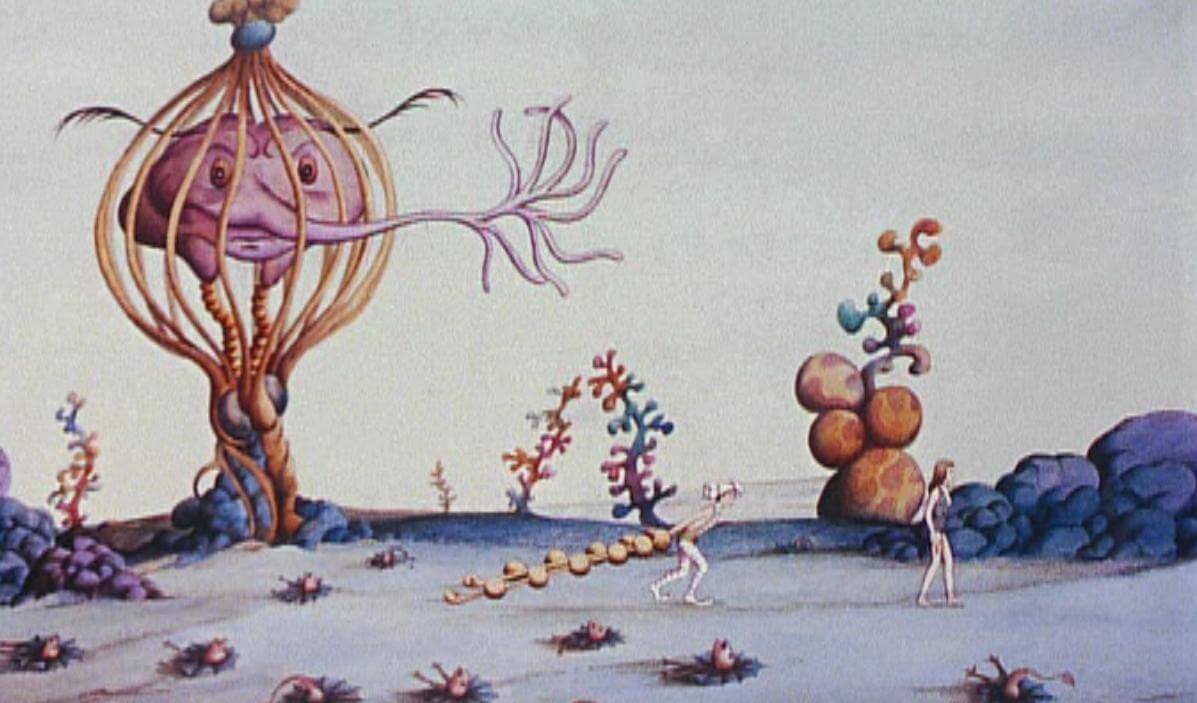

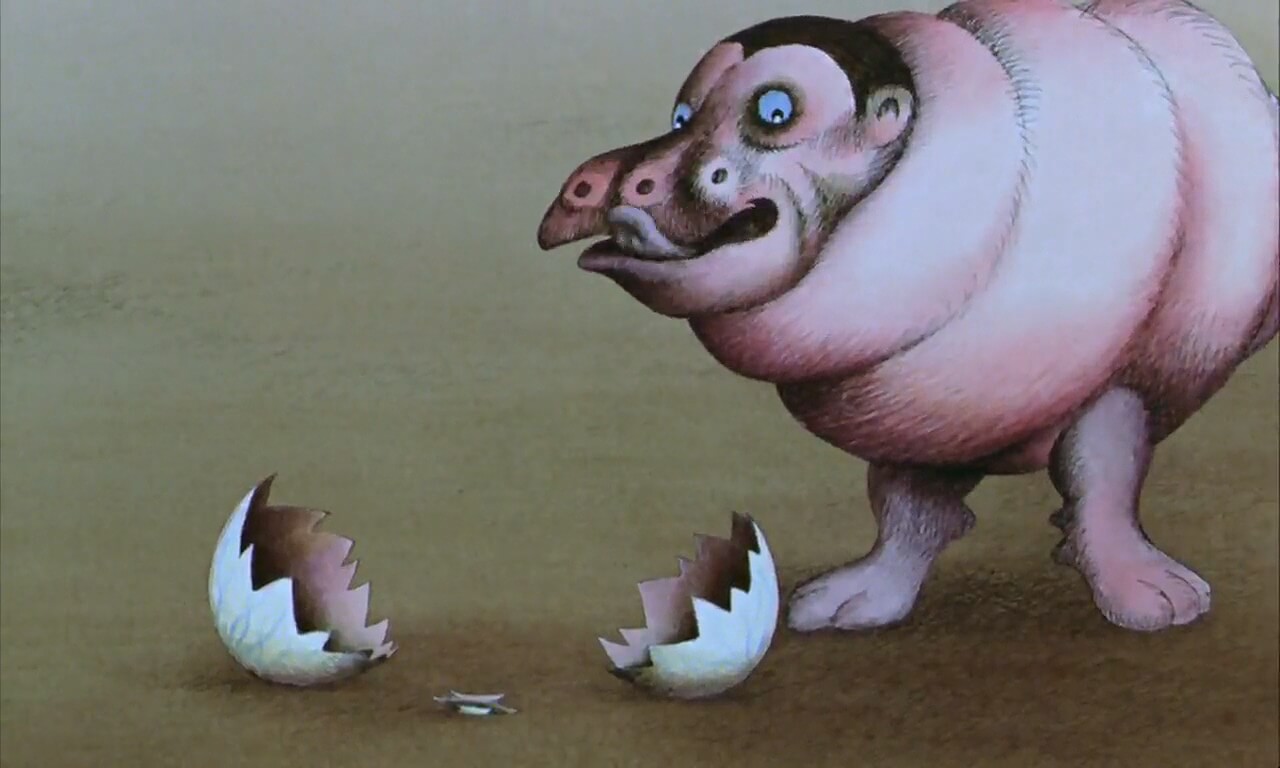

Visionary. Freshness. Uniqueness. And yet, the film premiered in 1973, over fifty years ago! Since then, the broadly defined genre of science fiction has incredibly evolved: Star Wars, the Alien series, Star Trek, Terminator, etc. And yet, the Franco-Czech animation about blue aliens remains, despite the passage of time, incredibly original and innovative. This is thanks to the creators—René Laloux and Roland Topor. Laloux honed his artistic skills while working at a French psychiatric hospital in Cour-Cheverny, where one of the doctors organized puppet theater as therapy. The other creator, Topor, was a versatile artist—writer, illustrator, actor, musician. Both gentlemen adapted the science fiction novel Oms en série, written in the 1950s by Stefan Wul (real name Pierre Pairault)—a dentist by profession, a writer by passion. Thanks to the creativity of the Laloux-Topor duo, Fantastic Planet took the form of a classic two-dimensional animation based on Topor’s colorful works. A world filled with bizarre creatures and techno-organic inventions emerged—a scene of drawn science fiction drama.

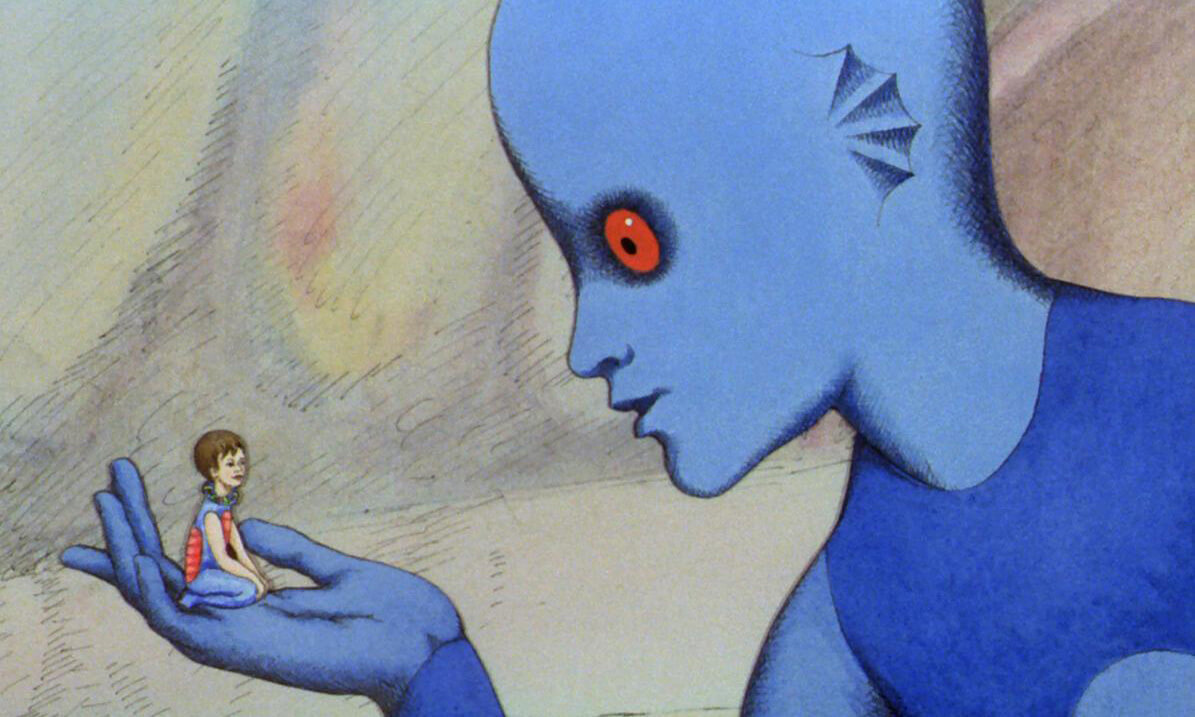

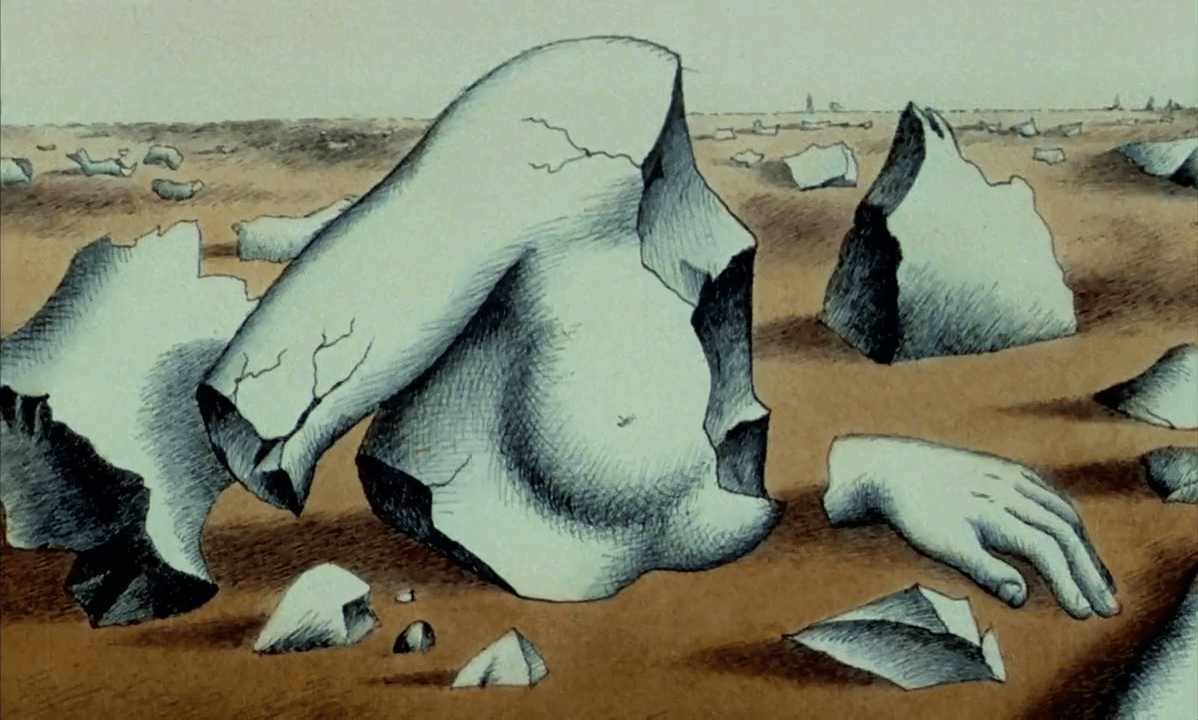

PROLOGUE of Fantastic Planet: A young, half-naked woman with a child in her arms runs with obvious terror through something resembling a forest. Clearly, she’s fleeing from something, looking back over her shoulder. She reaches a hill she wants to climb, but in her path appears… a hand. A huge, blue hand, which casually overturns the girl with a gentle movement. She gets up and stubbornly tries to pass, but her attempts end in failure. With a snap of its fingers, the powerful limb throws the tiny figure hugging the child backward. The sadistic game lasts a moment longer, and its finale is predictable—the woman caught in the blue fingers is dropped from a height and dies. Next to her, a helpless infant crawls.

– She’s not moving. – What a pity, we can’t play with her anymore!

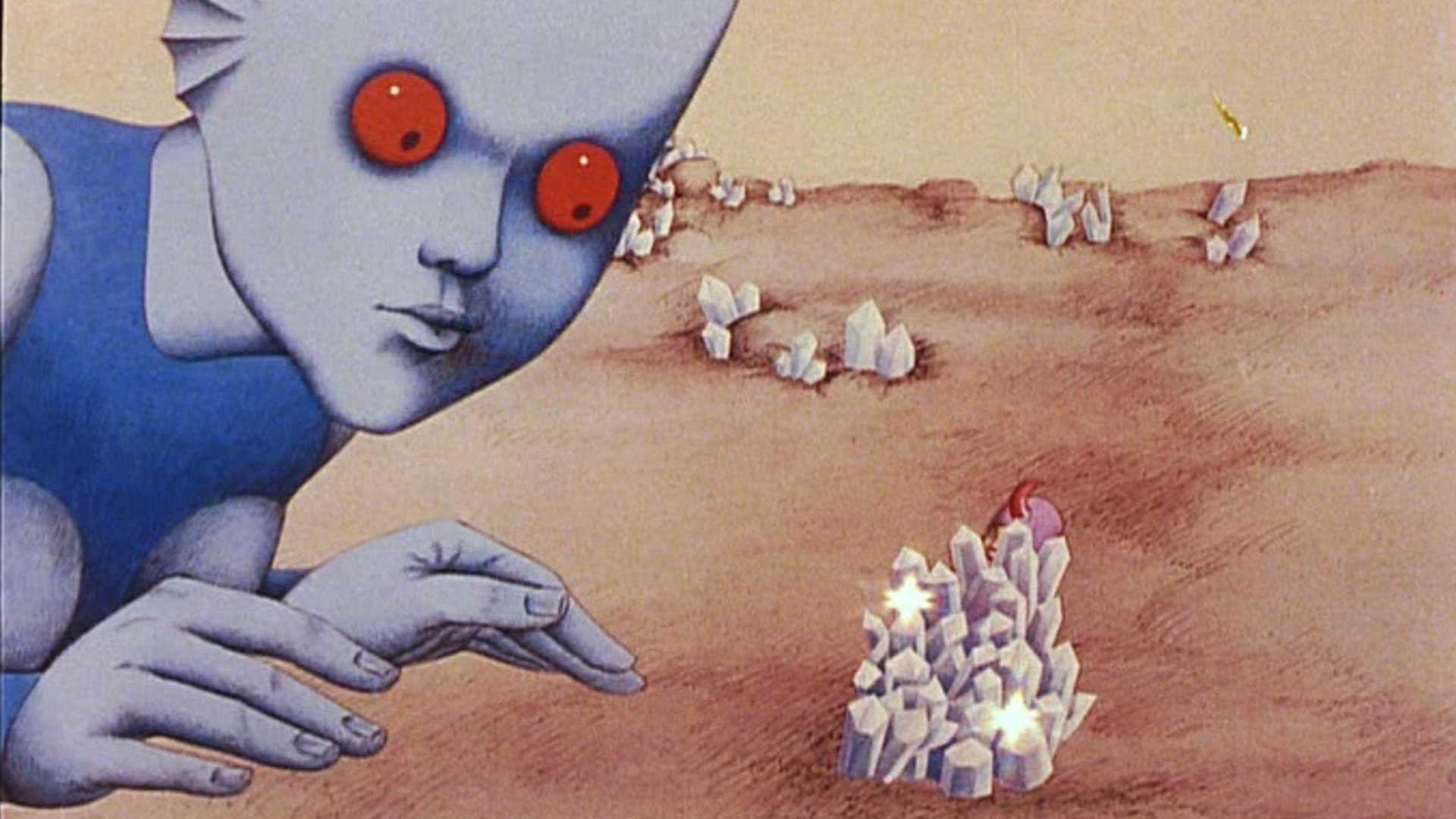

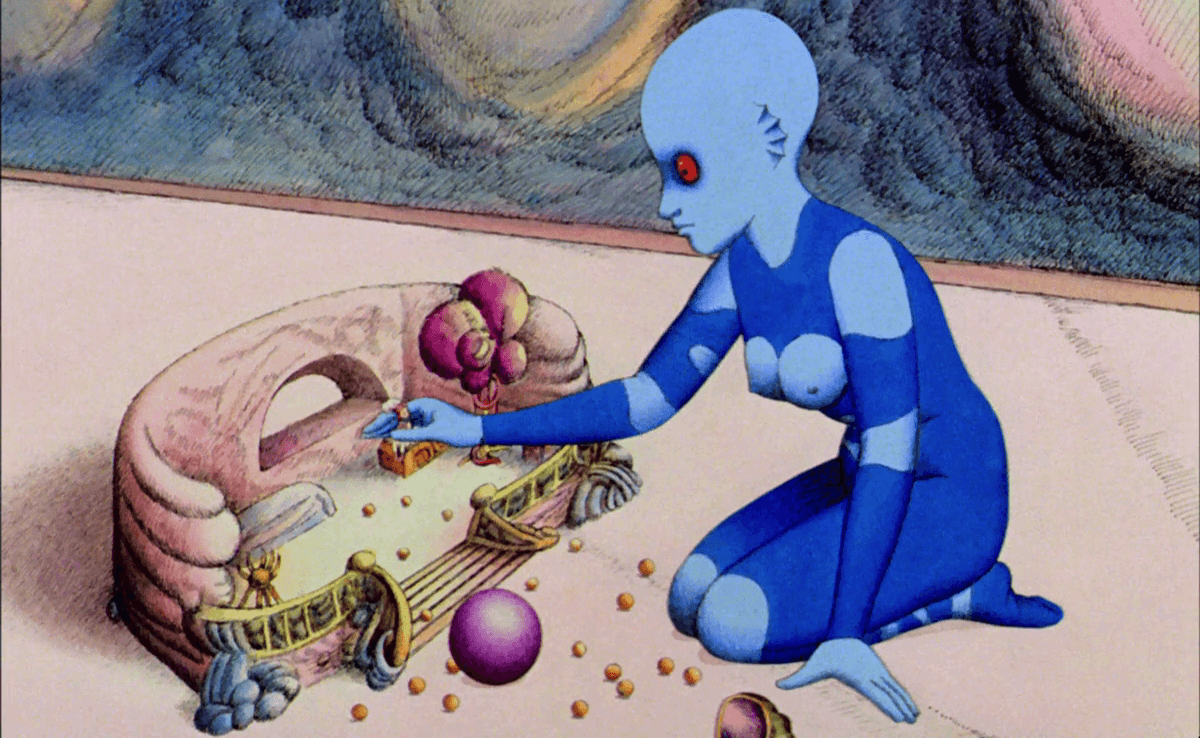

This dramatic introduction illustrates the mutual relations between the inhabitants of the planet Ygam: the dominant, advanced race of powerful Draags and the Om, limited to the role of living toys (from Fr. “l’homme”—man). Humans are leftovers, exterminated from time to time to prevent them from multiplying too quickly. The blue beings see no use or threat in the small creatures—often, however, they are present in Draag homes as mascots. Such is the fate of the orphaned child whose mother dies during the “game.” The lone Om is found by Tiwa, a Draag teenager. Moved by the creature’s fate, she persuades her father—the premier of the Draag community—to allow her to adopt the little being. Thus, the human child, named Terr, becomes the girl’s favorite pet. The enslaved human learns about the world from the perspective of a slave subjected to the whims of a higher race. Every day he is moved, positioned, dressed, and forced to perform acrobatics, with a collar preventing him from resisting. Tiwa, like a teenager from a good home, learns a lot—and she does it through headphones transmitting sounds and images directly to her brain.

It turns out that Terr is also sensitive to these signals and decides to learn alongside the girl. In this way, he begins to understand the language and alphabet of the Draags, learns their customs (e.g., regular meditation, allowing the blue beings to travel in the astral body). Over time, Tiwa grows up and finds other activities, abandoning toys and education. The abandoned Om decides to escape his captivity, but he takes with him his mistress’s scientific help to learn more. Although Terr manages to escape, he doesn’t quite know where to go, and he’s carrying huge, heavy headphones. Wandering through unfamiliar territory, he stumbles upon an abandoned park inhabited by a tribe of Wild Oms. His brethren turn out to be a collection of untamed, primitive beings, and he himself arouses suspicion with his knowledge. However, Terr gains respect and educates his fellow Oms, thereby developing their culture.

Fantastic Planet is not an easy film. The depressing, overwhelming prologue and first half of the screening present a grim vision of the world. Man here is an inconspicuous, pathetic creature, a small toy in the hands of a big child. The director smoothly transitions between threads, and the relatively short (72 minutes) animation is filled with information. Leloux creates the Oms as human equivalents in the depicted world, but in relation to the exotic race of Draags, the viewer doesn’t always side with the smaller and oppressed. Humans die at the hands of the blue beings as easily as a fly is killed by a human. In a morally clean and easy way. After all, it’s just a little pest. Fantastic Planet allows for an exploration of both the oppressor’s and the victim’s perspectives. Moreover, Terr is a Promethean figure (he steals knowledge from higher beings to share with his brethren) and a Spartacus-like character (after being freed, he leads the Wild Oms in a revolt against the ruling race).

These aren’t the only elements that can be interpreted symbolically. In one of the key moments of Fantastic Planet, there is a periodic extermination of Oms (called “deomization”). It’s apt to associate this with the Holocaust, and after the film’s premiere, Czechoslovak society sought allusions to the Prague Spring. However, all these mostly depressing scenes are watched with almost hypnotic attention. This is due to the exotic appearance of locations and creatures, transferred from Wul’s book to Topor’s drawings. The blue-skinned Draags with bulging, red eyes are both disturbing and intriguing. Both the vegetation and machinery present in the film look and function in a mysterious, non-obvious way. Like a specific combination of magic and engineering. The whole has a slightly comic book vibe; after all, every frame of this production looks great (after all, it’s hand-drawn by Topor).

The music and sound design of Fantastic Planet deserve a separate paragraph. The work done by the French jazzman, Alain Goraguer, is something incredible. Hypnotic, cyclically looping melodies penetrate the brain. Psychedelic guitar and keyboard sounds, supported by synthesizers, create compositions that linger in the memory long after the screening. It was Goraguer’s soundtrack from the film that inspired the band Air in their work on the phenomenal music for Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides. Goraguer’s tracks (once collaborating with Gainsbourg, among others) work perfectly as a standalone entity, constituting an atmospheric album lasting over an hour—ambient and unsettling.

Fantastic Planet is René Laloux’s cinematic debut. A remarkable debut not only for formal reasons and because of its message. The originality of this production must have made a big impression in the year of its release. Due to timeless themes and an enduring form, it still resonates with the audience today. It is a work that was created in interesting times. Just remember the Cannes festival, where the film received the Special Prize. In 1973, the competition included productions now considered classics in their genres—Schatzberg’s Scarecrow, Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe, and the controversial Jodorowsky with his The Holy Mountain. At that time, the jury prize went to Wojciech Jerzy Has for The Hour-Glass Sanatorium. Compared to the mentioned films, the animation about Draags and Oms seems almost niche. However, thanks to the inventiveness of the creators, the beautiful execution, and the power of the message, Fantastic Planet is an outstanding, wise, and still relevant work today. Maybe especially today.